Chapter 1 Sociology and the Study of Social Problems

Learning Objectives

- 1.1 Define the sociological imagination

- 1.2 Identify the characteristics of a social problem

- 1.3 Compare the four sociological perspectives

- 1.4 Explain how sociology is a science

- 1.5 Identify the role of social policy, advocacy, and innovation in addressing social problems

If I asked everyone in your class what they believe is the most important social problem facing the United States, there would be many different answers: the economy, immigration, health care, unemployment. Most would agree that some or all of these are social problems. But which is the most important, and how would we solve it?

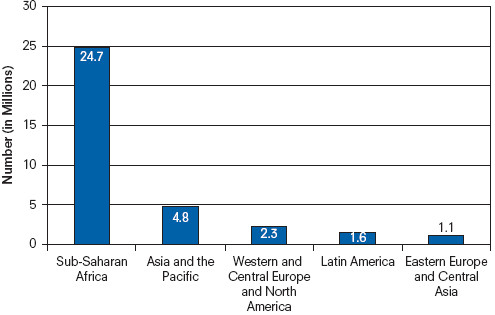

Suppose I asked the same question in a South African college classroom. AIDS is likely to be one of the responses from South African college students. According to UNAIDS (2014), 35 million adults and children worldwide were living with HIV in 2013. Africa remains the epicenter of the pandemic, with more than 25 million HIV-infected adults and children (refer to Figure 1.1). The prevalence of HIV is predicted to triple during the next decade, especially in Africa, but also in the former USSR, China, and India. The AIDS pandemic has been described as a threat to global stability (Lichtenstein 2004). However, effective risk-reduction strategies, along with new treatments for HIV/AIDS, have saved countless lives in the United States. During the early 1980s, nearly 150,000 Americans were infected with the disease each year, but by the early 1990s, the number of new infected cases had dropped to 50,000 per year, where it remains today (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007, 2013).

JON HRUSA/EPA/Newscom

Figure 1.1 Number of individuals living with HIV, regional data for 2013

SOURCE: UNAIDS 2014.

NOTE: The total number of HIV infections is 35 million. HIV infection data for the Caribbean (250,000) and Middle East and North Africa (230,000) are not reported in the figure.

Globalization, defined as the process of increasing transborder connectedness (Hytrek and Zentgraf 2007)—whether economically, politically, environmentally, or socially—poses new challenges and opportunities for understanding and solving social problems. We cannot understand the nature of social problems by simply taking a national or local perspective. Taking a global perspective allows us to look at the interrelations between countries and their social problems (Heiner 2002). We are not the only country to experience social problems. Knowledge based on research to understand and policies to address social problems here could be applied in other countries, and what other countries have learned based on their social problems could be applied in the United States. Finally, we all need a little help from our neighbors—we can increase our connectedness and goodwill with other countries through implementing solutions collaboratively rather than alone. So what do you think? Is HIV/AIDS in South Africa a problem only for South Africans, or is it also a problem for those living in the United States?

This is how we spend much of our public conversation—on the Senate floor, on afternoon talk shows, at work, or in the classroom—arguing, analyzing, and just trying to figure out which problem is most serious and what needs to be done about it. In casual or sometimes heated conversations, we offer opinions about the economy, the wars in the Middle East, the Affordable Care Act, or appropriate policies for the African AIDS pandemic. Often, these explanations are not based on firsthand data collection or on an exhaustive review of the literature. For the most part, they are based on our opinions and life experiences, or they are just good guesses.

What this text and your course offer is a sociological perspective on social problems. Unlike any other discipline, sociology provides us with a form of self-consciousness, an awareness that our personal experiences are often caused by structural or social forces. Sociology is the systematic study of individuals, groups, and social structures. A sociologist examines the relationship between individuals and society, which includes such social institutions as the family, the military, the economy, and education. As a social science, sociology offers an objective and systematic approach to understanding the causes of social problems. From a sociological perspective, problems and their solutions don’t just involve individuals; they also have a great deal to do with the social structures in our society. C. Wright Mills ([1959] 2000) first promoted this perspective in his 1959 essay, “The Promise.”

The Origin of AIDS

Using Our Sociological Imagination

According to Mills, the sociological imagination can help us distinguish between personal troubles and public issues. The sociological imagination is the ability to link our personal lives and experiences with our social world. Mills ([1959] 2000) describes how personal troubles occur within the “character of the individual and within the range of his immediate relationships with others” (p. 8), whereas public issues are a “public matter: some value cherished by publics is felt to be threatened” (p. 8). As a result, the individual, or those in contact with that individual, can resolve a trouble, but the resolution of an issue requires public debate about what values are being threatened and the source of such a threat.

Let’s consider unemployment. One man unemployed is his own personal trouble. Resolving his unemployment involves reviewing his current situation, reassessing his skills, considering his job opportunities, and submitting his résumés or job applications to employers. Once he has a new job, his personal trouble is over. However, what happens when your city or state experiences high levels of unemployment? What happens when there is a nationwide problem of unemployment? This affects not just one person but, rather, thousands or millions. A personal trouble has been transformed into a public issue. This is the case not just because of how many people it affects; something becomes an issue because of the public values it threatens. Unemployment threatens our sense of economic security. It challenges our belief that everyone can work hard to succeed. Unemployment raises questions about society’s obligations to help those without a job.

We can make the personal trouble–public issue connection with regard to another issue, one that you might already be aware of—the cost of higher education. In 2014, during a rally in Florida’s Coral Reef High School, President Barack Obama announced an initiative to help students complete the federal student aid application form, part of an effort to broaden access to higher education. Coral Reef senior David Scherker, an aspiring filmmaker, was in the audience. At the time, David was waiting to hear about the status of his admission to several colleges and universities, including Florida State University and USC. He worried about his financial aid offers and whether he would be able to attend the school of his choice (NPR 2014). Is this a personal trouble facing only David? Or is this a public issue?

A key distinction between a personal trouble and a public issue is how each one can be remedied. According to C. Wright Mills, an individual may be able to solve a trouble, but a public issue can only be resolved by society and its social structures.

Archive Photos / stringer

College cost has become a serious social problem because the “barriers that make higher education unaffordable serve to erode our economic well being, our civic values, and our democratic ideals” (Callan and Finney 2002:10). Although most Americans still believe that a college education is essential for one’s success, increasingly they also believe that qualified and motivated students do not have the opportunity to attend college (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education and Public Agenda 2010). The data support this. Nearly one half of all college-qualified, low- and moderate-income high school graduates are unable to afford college and have lower rates of bachelor’s degree attainment than their middle- and high-income peers (Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance 2006). Though only about a third of students pay the published tuition or sticker price, the cost of tuition has risen at a faster rate than family income or student financial aid. At a four-year public institution, for academic year 2013–2014, in-state total fees (tuition, room, and board) were $18,391 (a 3.2% increase from 2012–2013); at four-year private institutions, the average cost was $40,917 (a 3.7% increase from 2013–2014) (College Board 2014).

The majority of students receive some form of assistance through scholarships, federal grants, or state aid. The financial burden of a college education is unevenly distributed, with low- and moderate-income students and families experiencing the burden most. In 2007, even after grant aid, low-income families paid or borrowed an amount equivalent to 72% of their family income to cover one year of tuition. In contrast, families with incomes between $54,001 and $80,400 had to finance the equivalent of 27% of their family income for tuition. The percentage was lowest for families with incomes over $115,400 at 14% (Education Trust 2009). The average indebtedness for a graduating college senior was $28,400 for 2013 (Institute for College Access & Success 2014).

As Mills explains, “to be aware of the ideal of social structure and to use it with sensibility is to be capable of tracing such linkages among a great variety of milieus. To be able to do that is to possess the sociological imagination” (Mills [1959] 2000:10–11). The sociological imagination challenges the claim that the problem is “natural” or based on individual failures, instead reminding us how the problem is rooted in society, in our social structures themselves (Irwin 2001). For example, can we solve unemployment by telling every unemployed person to work harder? Can David solve his tuition problem by taking out student loans? Or will this create additional problems? The sociological imagination emphasizes the structural bases of social problems, making us aware of the economic, political, and social structures that govern employment and unemployment trends and the cost of higher education. Individuals have may agency, the ability to make their own choices, but their actions and even their choices may be constrained by the realities of the social structure. Throughout this text, we apply our sociological imagination to the study of social problems. Before we proceed, we need to understand what a social problem is.

College Costs and Alternatives

Rising College Costs

What Is a Social Problem?

The Negative Consequences of Social Problems

A social problem is a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world. A social problem such as unemployment, alcoholism, drug abuse, or HIV/AIDS may negatively affect a person’s life and health, along with the well-being of that person’s family and friends. Problems can threaten our social institutions, for example, the family (spousal abuse), education (the rising cost of college tuition), or the economy (unemployment). Our physical and social worlds can be threatened by problems related to urbanization (lack of affordable housing) and the environment (climate change). You will note from the examples in this paragraph that social problems are inherently social in their causes, consequences, and solutions.

Objective and Subjective Realities of Social Problems

A social problem has objective and subjective realities. A social condition does not have to be personally experienced by every individual to be considered a social problem. The objective reality of a social problem comes from acknowledging that a particular social condition does exist. Objective realities of a social problem can be confirmed by collection of data. For example, we know from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013) that more than 1.1 million Americans are living with HIV/AIDS. Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for more information about HIV infections in the United States. You or I do not have to have been infected with HIV to know that the disease is real, with real human and social consequences. We can confirm the realities of HIV/AIDS by observing infected individuals and their families in our own community, at AIDS programs, shelters, or hospitals.

The subjective reality of a social problem addresses how a problem becomes defined as a problem. This idea is based on the concept of the social construction of reality. Coined by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (1966), the term refers to how our world is a social creation, originating and evolving through our everyday thoughts and actions. Most of the time, we assume and act as though the world is a given, objectively predetermined outside our existence. However, according to Berger and Luckmann, we also apply subjective meanings to our existence and experience. In other words, our experiences don’t just happen to us. Good, bad, positive, or negative—we attach meanings to our reality.

From this perspective, social problems are not objectively predetermined. They become real only when they are subjectively defined or perceived as problematic. This perspective is known as social constructionism. Recognizing the subjective aspects of social problems allows us to understand how a social condition may be defined as a problem by one segment of society but be completely ignored by another. For example, do you believe AIDS is a social problem? Some may argue that it is a problem only if you are the one infected with the disease or if you are morally corrupt or sexually promiscuous. Actually, some would not consider AIDS a problem at all, considering the medical and public health advances that have successfully reduced the spread of the disease in the United States. Yet others would argue that AIDS still qualifies as a social problem.

Sociologist Denise Loseke (2003) explains, “Conditions might exist, people might be hurt by them, but conditions are not social problems until humans categorize them as troublesome and in need of repair” (p. 14). To frame their work, social constructionists ask the following set of questions:

What do people say or do to convince others that a troublesome condition exists that must be changed? What are the consequences of the typical ways that social problems attract concern? How do our subjective understandings of social problems change the objective characteristics of our world? How do these understandings change how we think about our own lives and the lives of those around us? (Loseke and Best 2003:3–4)

The social constructionist perspective focuses on how a problem is socially defined, in a dialectic process between individuals interacting with each other and with their social world. In the next section, we’ll learn how the problem of HIV/AIDS was socially constructed.

Unemployment and the Great Recession

Exploring social problems

HIV and AIDS

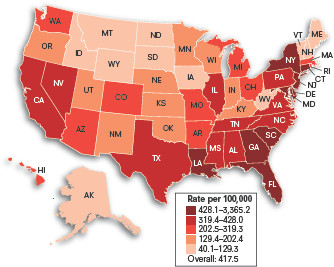

U.S. Data Map 1.1 Rates of persons aged 18–64 years living with a diagnosis of HIV infection, 2008

Data Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013.

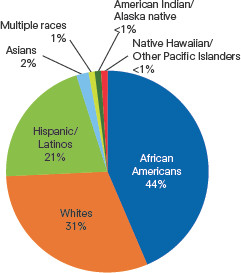

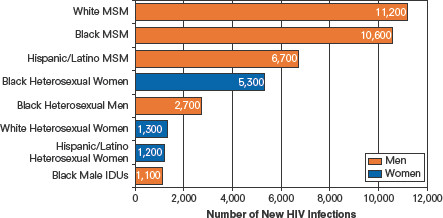

Figure 1.2 New HIV infections by race/ethnicity, 2010

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014.

Figure 1.3 Estimated new HIV infections, 2010, for the most affected subpopulations

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014.

NOTE: MSM stands for “men who have sex with men.” IDU stands for “injecting drug user.”

What Do You Think?

- More than 1.1 million Americans are living with HIV/AIDS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013).

- Despite representing 12% of the U.S. population, African Americans accounted for 44% of all new HIV infections among adults and adolescents (13 years or older) in 2010 (refer to Figure 1.2). Gay and bisexual men account for most of the new infections among whites and African Americans. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are most at risk for HIV infections (refer to Figure 1.3).

- How should health programs or policies address the risk factors for these populations? What structural barriers might make these populations difficult to reach?

- Which groups have the lowest number of new HIV infections?

The History of Social Problems

Problems don’t appear overnight; rather, as Malcolm Spector and John Kituse (1987) argue, the identification of a social problem is part of a subjective process. Spector and Kituse identify four stages to the process. Stage 1 is defined as a transformation process: taking a private trouble and transforming it into a public issue. In this stage, an influential group, activists, or advocates call attention to and define an issue as a social problem. The first HIV infection cases were documented in the United States in 1979. The disease was originally referred to as the “gay plague” because the first group to be identified with the disease was gay men from San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. The association of HIV/AIDS with this specific population led to its first being defined as a sexual epidemic rather than a public health threat. Gay activists and public health officials mobilized to increase awareness and began to change the public’s perception of the disease in the early 1980s.

Stage 2 is the legitimization process: formalizing the manner in which the social problems or complaints generated by the problem are handled. For example, an organization or public policy could be created to respond to the condition. An existing organization, such as a federal or state agency, could also be charged with taking care of the situation. In either instance, these organizations begin to legitimize the problem by creating and implementing a formal response. In the early 1980s, HIV/AIDS task forces were created in the CDC and the World Health Organization. Similar groups were convened in the United Kingdom, France, and other countries. Although no single organization or country was in charge, all were intent on identifying the disease and finding a cure. Activists looked for public legitimization of the disease from then President Ronald Reagan. But Reagan did not acknowledge AIDS until 1985, when he was asked directly about the disease during a press conference. His first public statement about the disease came in 1987 at the Third International Conference on AIDS. By then, nearly 36,000 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS and more than 20,000 had died. AIDS advocates blamed Reagan’s slow and ineffective response for these deaths and the increasing spread of the disease.

Stage 3 is a conflict stage, when Stage 2 routines are unable to address the problem. During Stage 3, activists, advocates, and victims of the problem experience feelings of distrust and cynicism toward the formal response organizations. Stage 3 activities include readjusting the formal response system: renegotiating procedures, reforming practices, and engaging in administrative or organizational restructuring. Many early public health protocols were revised in response to increased understanding about how HIV/AIDS is spread and treated. For example, patient isolation was common during the first stages of the disease. Teenager Ryan White had to petition for the right to attend public school with his classmates. Ryan and his mother’s experiences also shed light on the difficulties faced by low-income, uninsured, or underinsured individuals and families living with HIV/AIDS. After his death in 1990, the U.S. Congress passed the Ryan White CARE Act to provide for the unmet health needs of individuals with HIV/AIDS. The act continues to provide support for nearly 500,000 individuals annually, making it the largest federal government program for those living with the disease.

Finally, Stage 4 begins when groups believe that they can no longer work within the established system. Advocates or activists are faced with two options: to radically change the existing system or to work outside the system. As an alternative to the government and public health agencies’ response to HIV/AIDS, numerous independent advocacy and research groups were formed. One such group is AIDS United (first called AIDS Action), formed in 1984 by a coalition of AIDS service organizations. In an effort to end AIDS in our country, AIDS United embraced a multi-strategy of research, granting funding, policy making, and advocacy. Through its Access to Care program, AIDS United supports innovative, evidence-based, collaborative programs serving low-income and marginalized individuals living with HIV. Access to Care not only supports the health and care of HIV patients, but also provides job training, housing stabilization, and peer support (AIDS United 2014).

Taking a World View

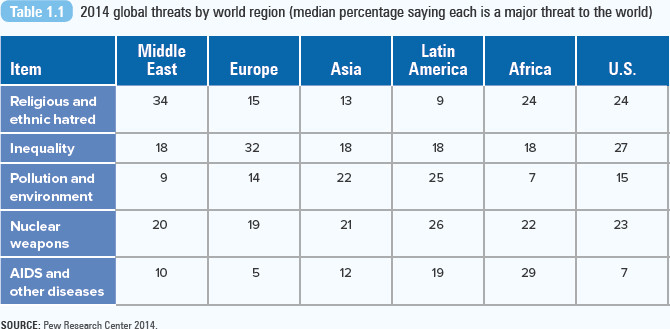

Identifying the Greatest Threat to the World

In 2014, the Pew Research Center asked residents in 44 countries what they perceived as the greatest threat to the world. According to the Center, “across the nations surveyed, opinions on which of the five dangers is the top threat to the world vary greatly by region and country, and in many places there is no clear consensus.” Results are grouped in six regions presented in Table 1.1.

Inequality was more likely to be identified by citizens of advanced economies. More than a quarter of surveyed Americans and a third of surveyed Europeans selected inequality as the greatest threat. The EU country with the highest level of concern was Spain (54%). Inequality was of less concern in the other reported world regions—the Middle East, Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Note how AIDS and other diseases are of great concern to African residents (29%), but of lowest concern in the United States (7%) and Europe (5%). Religious and ethnic hatred was identified as the top threat to the world by citizens in Middle Eastern countries (34%). Nuclear weapons (26%) and pollution (25%) were the greatest threats for Latin American respondents.

Which of these do you think is the greatest threat to the world?

SOURCE: Pew Research Center 2014.

In Focus

A Review of Sociology

According to Jeanne Ballantine and Keith Roberts (2012), sociologists examine the software and hardware of society. A society consists of individuals who live together in a specific geographic area, who interact with each other, and who cooperate for the attainment of common goals.

The software is our culture. Each society has a culture that serves as a system of guidelines for living. A culture includes norms (rules of behavior shared by members of society and rooted in a value system), values (shared judgments about what is desirable or undesirable, right or wrong, good or bad), and beliefs (ideas about life, the way society works, and where one fits in).

The hardware comprises the enduring social structures that bring order to our lives. This includes the positions or statuses that we occupy in society (student, athlete, employee, roommate) and the social groups to which we belong and identify with (our family, our local place of worship, our workplace). Social institutions are the most complex hardware. Social institutions, such as the family, religion, or education, are relatively permanent social units of roles, rules, relationships, and organized activities devoted to meeting human needs and to directing and controlling human behavior (Ballantine and Roberts 2012).

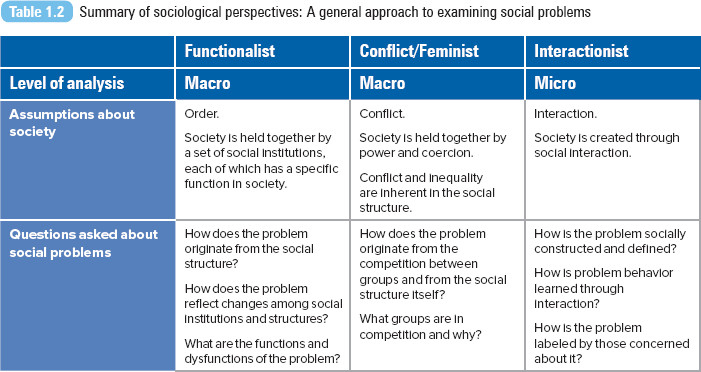

Understanding the Sociological Perspective

The way sociologists conduct sociology and study social problems begins first with their view on how the world works. Based on a theory—a set of assumptions and propositions used for explanation, prediction, and understanding—sociologists begin to define the relationship between society and individuals and to describe the causes and consequences of social problems.

Theories vary in their level of analysis, focusing on a macro (societal) or a micro (individual) level of analysis. Theories help inform the direction of sociological research and data analysis. In the following section, we review four theoretical perspectives—functionalist, conflict, feminist, and interactionist—and how each perspective explains and examines social problems. Research methods used by sociologists are summarized in the next section.

Functionalist Perspective

Among the theorists most associated with the functionalist perspective is French sociologist Émile Durkheim. Borrowing from biology, Durkheim likened society to a human body. As the body has essential organs, each with a specific function, he theorized that society has its own organs: institutions such as the family, religion, education, economics, and politics. These organs or social structures have essential and specialized functions. For example, the institution of the family maintains the health and socialization of our young and creates a basic economic unit. The institution of education provides knowledge and skills for women and men to work and live in society. No other institution can do what the family or education does.

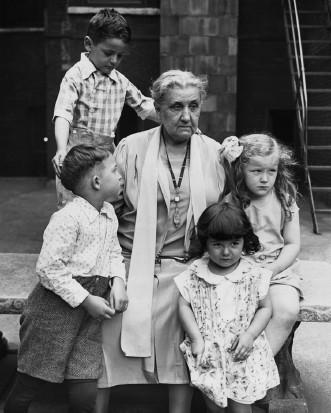

Jane Addams’ (center) sociological perspective informed her connection to her Chicago community and led her to a life of social action. She developed programs to assist the poor and advocated for legislative and political reforms.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62- 37768]

Durkheim proposed that the function of society is to civilize or control individual actions. He wrote, “It is civilization that has made man what he is; it is what distinguishes him from the animal: man is man only because he is civilized” (Durkheim [1914] 1973:149). The social order can be threatened during periods of rapid social change, such as industrialization or political upheaval, when social norms and values are likely to be in transition. During this state of normlessness or anomie, Durkheim believed, society is particularly prone to social problems. As a result, social problems cannot be solved by changing the individual; rather, the problem has to be solved at the societal level. The entire social structure or the affected part of the social structure needs to be repaired.

The functionalist perspective, as its name suggests, examines the functions or consequences of the structure of society. Functionalists use a macro perspective, focusing on how society creates and maintains social order. Social problems are not analyzed in terms of how “bad” they are for society. Rather, a functionalist asks, how does the social problem emerge from society? Does the social problem serve a function?

The systematic study of social problems began with the sociologists at the University of Chicago. Part of what has been called the Chicago School of Sociology, scholars such as Ernest W. Burgess, Homer Hoyt, Robert E. Park, Edward Ullman, and Louis Wirth used their city as an urban laboratory, pursuing field studies of poverty, crime, and drug abuse during the 1920s and 1930s. Through their research, they captured the real experiences of individuals experiencing social problems, noting the positive and negative consequences of urbanization and industrialization (Ritzer 2000). Taking it one step further, sociologists Jane Addams and Charlotte Gilman studied urban life in Chicago and developed programs to assist the poor and lobbied for legislative and political reform (Adams and Sydie 2001).

According to Robert Merton (1957), social structures can have positive benefits as well as negative consequences, which he called dysfunctions. A social problem such as homelessness has a clear set of dysfunctions but can also have positive consequences or functions. One could argue that homelessness is clearly dysfunctional and unpleasant for the women, men, and children who experience it, and for a city or community, homelessness can serve as a public embarrassment. Yet, a functionalist would say that homelessness is beneficial for at least one part of society, or else it would cease to exist. The population of the homeless supports an industry of social service agencies, religious organizations, and community groups and service workers. In addition, the homeless also highlight problems in other parts of our social structure, namely, the problems of the lack of a livable wage or affordable housing.

Diversity as Dysfunction

Conflict Perspective

Like functionalism, conflict theories examine the macro level of our society, its structures and institutions. Whereas functionalists argue that society is held together by norms, values, and a common morality, those holding a conflict perspective consider how society is held together by power and coercion (Ritzer 2000) for the benefit of those in power. In this view, social problems emerge from the continuing conflict between groups in our society—based on social class, gender, race, or ethnicity—and in the conflict, the dominant groups usually win. There are multiple levels of domination; as Patricia Hill Collins (1990) describes, domination “operates not only by structuring power from the top down but by simultaneously annexing the power as energy of those on the bottom for its own ends” (pp. 227–28).

As a result, this perspective offers no easy solutions to social problems. The system could be completely overhauled, but that is unlikely to happen. We could reform parts of the structure, but those in power would retain their control. The biggest social problem from this perspective is the system itself and the inequality it perpetuates.

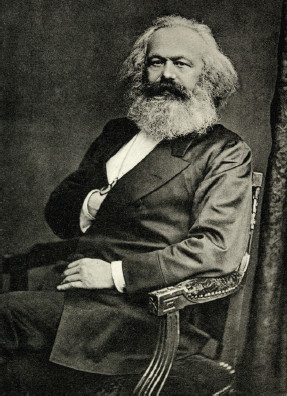

The first to make this argument was German philosopher and activist Karl Marx. Conflict, according to Marx, emerged from the economic substructure of capitalism, which defined all other social structures and social relations. He focused on the conflict based on social class, created by the tension between the proletariat (workers) and the bourgeoisie (owners). Capitalism did more than separate the haves and the have-nots. Unlike Durkheim, who believed that society created a civilized man, Marx argued that a capitalist society created a man alienated from his species being, from his true self. Alienation occurred on multiple levels: man would become increasingly alienated from his work, the product of his work, other workers, and, finally, his own human potential. For example, a salesperson might be so involved in the process of her work that she doesn’t spend quality time with her coworkers, talk with her customers, or stop and appreciate the merchandise. Each sale transaction is the same; all customers and workers are treated alike. The salesperson cannot achieve her human potential through this type of mindless unfulfilling labor. According to Marx, workers needed to achieve a class consciousness, an awareness of their social position and oppression, so they could unite and overthrow capitalism, replacing it with a more egalitarian socialist and eventually communist structure.

From a conflict perspective, all social problems could be traced back to the economic substructure of capitalism. According to Karl Marx, the organization of capitalist labor eroded one’s human potential or what he refered to as species being.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0a/Marx7.jpg

Widening Marx’s emphasis on the capitalist class structure, contemporary conflict theorists have argued that conflict emerges from other social bases, such as values, resources, and interests. Mills ([1959] 2000) argued the existence of a “power elite,” a small group of political, business, and military leaders who control our society. Ralf Dahrendorf (1959) explained that conflict of interest is inherent in any relationship because those in powerful positions will always seek to maintain their dominance. Lewis Coser (1956) focused on the functional aspects of conflict, arguing that conflict creates and maintains group solidarity by clarifying the positions and boundaries between groups. Conflict theorists may also take a social constructionist approach, examining how powerful political, economic, and social interest groups subjectively define social problems.

Feminist Perspective

Rosemarie Tong (1989) explains that “feminist theory is not one, but many, theories or perspectives and that each feminist theory or perspective attempts to describe women’s oppression, to explain its causes and consequences, and to prescribe strategies for women’s liberation” (p. 1). By analyzing the situations and lives of women in society, the feminist perspective defines gender (and sometimes race or social class) as a source of social inequality, group conflict, and social problems. For feminists, the patriarchal society is the basis of social problems. Patriarchy refers to a society in which men dominate women and justify their domination through devaluation; however, the definition of patriarchy has been broadened to include societies in which powerful groups dominate and devalue the powerless (Kaplan 1994).

Patricia Madoo Lengermann and Jill Niebrugge-Brantley (2004) explain that feminist theory was established as a new sociological perspective in the 1970s, largely because of the growing presence of women in the discipline and the strength of the women’s movement. Feminist theory treats the experiences of women as the starting point in all sociological investigations, seeing the world from the vantage point of women in the social world and seeking to promote a better world for women and for humankind.

Individuals come together in public rallies to voice their concerns about HIV/AIDS policies and funding. These demonstrations galvanize the efforts of advocacy and activist groups, as well as educate the public about HIV/AIDS.

SHANNON STAPLETON/Reuters

Although the study of social problems is not the center of feminist theory, throughout its history, feminist theory has been critical of existing social arrangements and has focused on such concepts as social change, power, and social inequality (Madoo Lengermann and Niebrugge-Brantley 2004). Major research in the field has included Jessie Bernard’s ([1972] 1982) study of gender inequality in marriage, Collins’s (1990) development of Black feminist thought, Dorothy Smith’s (1987) sociology from the standpoint of women, and Nancy Chodorow’s (1978) psychoanalytic feminism and reproduction of mothering. Although sociologists in this perspective may adopt a conflict, functionalist, or interactionist perspective, their focus remains on how men and women are situated in society, not just differently but also unequally (Madoo Lengermann and Niebrugge-Brantley 2004).

Misogyny in the Music Industry

Interactionist Perspective

An interactionist perspective focuses on how we use language, words, and symbols to create and maintain our social reality. This micro-level perspective highlights what we take for granted: the expectations, rules, and norms that we learn and practice without even noticing. In our interaction with others, we become the products and creators of our social reality. Through our interaction, social problems are created and defined. More than any other perspective, interactionists stress human agency—the active role of individuals in creating their social environment (Ballantine and Roberts 2012).

George Herbert Mead provided the foundation of this perspective. Also a member of the Chicago School of Sociology, Mead ([1934] 1962) argued that society consists of the organized and patterned interactions among individuals. As Mead defined it, the self is a mental and social process, the reflective ability to see others in relation to ourselves and to see ourselves in relation to others. Our interactions are based on language, based on words. The words we use to communicate with are symbols, representations of something else. The symbols have no inherent meaning and require human interpretation. The term symbolic interactionism was coined by Herbert Blumer in 1937. Building on Mead’s work, Blumer emphasized how the existence of mind, self, and society emerge from interaction and the use and understanding of symbols (Turner 1998).

How does the self emerge from interaction? Consider the roles that you and I play. As a university professor, I am aware of what is expected of me; as university students, you are aware of what it means to be a student. There are no posted guides in the classroom that instruct us where to stand, how to dress, or what to bring to class. Even before we enter the classroom, we know how we are supposed to behave and even our places in the classroom. We act based on our past experiences and based on what we have come to accept as definitions of each role. But we need each other to create this reality; our interaction in the classroom reaffirms each of our roles and the larger educational institution. Imagine what it takes to maintain this reality: consensus not just between a single professor and his or her students but between every professor and every student on campus, on every university campus, ultimately reaffirming the structure of a university classroom and higher education.

So, how do social problems emerge from interaction? First, for social problems such as juvenile delinquency, an interactionist would argue that the problem behavior is learned from others. According to this perspective, no one is born a juvenile delinquent. Like any other role we play, people learn how to become juvenile delinquents. Although the perspective does not answer the question of where or from whom the first delinquent child learned this behavior, it attempts to explain how deviant behavior is learned through interaction with others.

Second, social problems emerge from the definitions themselves. Objective social problems do not exist; they become real only in how they are defined or labeled. A sociologist using this perspective would examine who or what group is defining the problem and who or what is being defined as deviant or a social problem. As we have already seen with the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States, the problem became real only when activists and public health workers called attention to the disease.

Third, the solutions to social problems also emerge from our definitions. Helen Schneider and Anne Ingram (1993) argued that the social construction of target populations influences the distribution of policy benefits or policy burdens. Target populations are groups of individuals experiencing a specific social problem; these groups gain policy attention through their socially constructed identity and political power. The authors identified four categories: advantaged target populations are positively constructed and politically powerful (likely to receive policy benefits), contenders are politically powerful yet negatively constructed (likely to receive policy benefits when public interest is high), dependent target populations have positive social construction but low political power (few policy resources would be allocated to this group), and deviant target populations are both politically weak and negatively constructed (least likely to receive any benefits).

Jean Schroedel and Daniel Jordan (1998) applied the target population model to U.S. Senate voting patterns between 1982 and 1992, examining the allocation of federal funds to four distinct HIV/AIDS groups. As Schneider and Ingram’s (1993) theory would predict, the groups receiving the most funding were those in the advantaged category (war veterans and health care workers), followed by contenders (gay and bisexual men and the general population with AIDS), dependents (spouses and the public), and, finally, deviants (IV drug users, criminals, and prisoners).

The Science of Sociology

Sociology is not commonsense guessing about how the world works. The social sciences rely on “scientific methods to investigate individuals, societies, and social process” and encompass “the knowledge produced by these investigations” (Schutt 2012:9).

Sociological research is divided into two areas: basic and applied. The knowledge we gain through basic research expands our understanding of the causes and consequences of a social problem, for example, identifying the predictors of HIV/AIDS or examining the rate of homelessness among AIDS patients. Conversely, applied research involves the pursuit of knowledge for program application or policy evaluation (Katzer, Cook, and Crouch 1998); effective program practices documented through applied research can be incorporated into social and medical programs serving HIV/AIDS patients.

Some social scientists disagree about the applied use of data, arguing that the role of science is to describe the world as it is. Others (like me) acknowledge how research and data can inform our understanding of a social problem and consequently identify a solution or a path to some desired change. While the goal of research is to achieve an empirical understanding of our social world, it is not to say that values do not influence the research process. Max Weber, one of the discipline’s founders, described how research should have value-relevance. Though he believed that data collection and data analysis should be objectively conducted, Weber noted how “the choice of objects to study would be made on the basis of what is considered important in the particular society in which the researchers live” (Ritzer 2008: 123). Social problems research is important, not only for expanding what we know about the causes and consequences of problems, but also for identifying what can be done to address them.

All research begins with a theory to help identify the phenomenon we’re trying to explain and provide explanations for the social patterns or causal relationships between variables (Frankfort-Nachmias and Leon-Guerrero 2013). Variables are a property of people or objects that can take on two or more values. For example, as we try to explain HIV/AIDS, we may have a specific explanation about the relationship between two variables—social class and HIV infection. Social class could be measured according to household or individual income, whereas HIV infection could be measured as a positive test for the HIV antibodies. The relationship between these variables can be stated in a hypothesis, a tentative statement about how the variables are related to each other. We could predict that HIV infection would be higher among lower-income men and women. In this hypothesis statement, we’ve identified a dependent variable (the variable to be explained, HIV infection) along with an independent variable (the variable expected to account for the cause of the dependent variable, social class). Data, the information we collect, may confirm or refute this hypothesis.

Research methods can include quantitative or qualitative approaches or a combination. Quantitative methods rely on the collection of statistical data. They require the specification of variables and scales collected through surveys, interviews, or questionnaires. Qualitative methods are designed to capture social life as participants experience it. These methods involve field observation, depth interviews, or focus groups. Following are definitions of each specific method.

Survey research: This is data collection based on responses to a series of questions. Surveys can be offered in several formats: a self-administered mailed survey, group surveys, in-person interviews, or telephone surveys. For example, information from HIV/AIDS patients may be collected by a survey sent directly in the mail or by a telephone or in-person interview (e.g., Simoni et al. 2006; Sambisa, Curtis, and Mishra 2010).

Qualitative methods: This category includes data collection conducted in the field, emphasizing the observations about natural behavior as experienced or witnessed by the researcher. Methods include participant observation (a method for gathering data that involves developing a sustained relationship with people while they go about their normal activities), focus groups (unstructured group interviews in which a focus group leader actively encourages discussion among participants on the topics of interest), or intensive (depth) interviewing (open-ended, relatively unstructured questioning in which the interviewer seeks in-depth information on the interviewee’s feelings, experiences, and perceptions). Sociologists have used various qualitative methods in HIV/AIDS research—collecting data through participant observation at clinics or support groups and focus groups or depth interviews with patients, health care providers, or key informants (e.g., Chakrapani et al. 2007; Akintola 2010).

Historical and comparative methods: This is research that focuses on one historical period (historical events research) or traces a sequence of events over time (historical process research). Comparative research involves multiple cases or data from more than one time period. For example, researchers have examined the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS treatments over time (e.g., Fumaz et al. 2007) and compared infection rates between men and women (e.g., Ballesteros et al. 2006).

Secondary data analysis: Secondary data analysis usually involves the analysis of previously collected data that are used in a new analysis. Large public survey data sets, such as the U.S. Census, the General Social Survey, the National Election Survey, or the International Social Survey Programme, can be used, as can data collected in experimental studies or with qualitative data sets. For HIV/AIDS research, a secondary data analysis could be based on existing medical records (e.g., Tabi and Vogel 2006) or a routine health survey (e.g., Sambisa et al. 2010). The key to secondary data analysis is that the data were not originally collected by the researcher but were collected by another researcher and for a different purpose.

Voices in the Community

Judith Auerbach

Since earning her PhD in Sociology from the University of California, Berkeley, Judith Auerbach has been working outside academia on HIV/AIDS medical research and health policy issues related to women. Throughout her career, Auerbach has had many distinguished appointments—assistant director for social and behavioral sciences in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, senior program officer at the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences, director of the Behavioral and Social Science Program and HIV prevention science coordinator in the Office of AIDS Research at the National Institutes of Health, and vice president for public policy and program development at amfAR. Currently Auerbach is an adjunct professor in the School of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

In 2011, Auerbach described her role as a public sociologist:

I have a PhD in sociology, but I have chosen to work outside of academia almost all of my career—in government, research, policy, advocacy and community-based organizations. In all these domains, I have attempted to bring the insights of sociology to bear on medical research and health policy deliberations focused on HIV/AIDS, women’s health and gender equity. (quoted in International AIDS Society 2011)

This has sometimes been a challenging role, as I am usually the lone social scientist in the biomedical conversation, particularly around so-called “biomedical technologies” for HIV prevention. Having to constantly educate and convince others about the existence and contributions of social science is exhausting and frustrating. It boggles me that I still have to make the case for understanding the relational and contextual nature of HIV transmission and the need to recognize that people and technologies are interactive and interdependent. But, I have seen progress in recent years, so I’m happy to keep playing the social science missionary through my publications, presentations, and inputs at meetings and conferences. (quoted in Mapping Pathways 2011)

Auerbach and her research colleagues are collecting qualitative data on women’s attitudes and knowledge about taking a daily oral pill as part of an HIV prevention protocol. They advocate shifting the HIV/AIDS public health response “from an ‘emergency’ approach to a longer-term response” (quoted in Mapping Pathways 2011) addressing the maintenance of the disease and its transmission.

What other social problems could a public sociologist study?

The Transformation From Problem to Solution

Although Mills identified the relationship between a personal trouble and a public issue, less has been said about the transformation of issue to solution. Mills leads us in the right direction by identifying the relationship between public issues and social institutions. By continuing to use our sociological imagination and recognizing the role of larger social, cultural, and structural forces, we can identify appropriate measures to address these social problems. Mills ([1959] 2000) suggests that “the educational and political role of social science in a democracy is to help cultivate and sustain publics and individuals that are able to develop, to live with, and to act upon adequate definitions of personal and social realities” (p. 192).

With more than 70 national organizations around the world, Habitat for Humanity is supported primarily by local volunteers. In this photo, volunteers from the Rochester Institute of Technology are building a home during their spring break in Wichita Falls, Texas.

AP Photo/Wichita Falls Times Record News, Torin Halsey

Modern history reveals that Americans do not like to stand by and do nothing about social problems. Actually, most Americans support efforts to reduce homelessness, improve the quality of education, or find a cure for HIV/AIDS. In some cases, there are no limits to our efforts. Helping our nation’s poor has been an administrative priority of many U.S. presidents. President Franklin Roosevelt proposed sweeping social reforms during his New Deal in 1935, and President Lyndon Johnson declared the War on Poverty in 1964. President Bill Clinton offered to “change welfare as we know it” with broad reforms outlined in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. In 2003, President George W. Bush supported the reauthorization of the 1996 welfare reform bill. During his term in office, President Obama addressed poverty through community development programs like the Promise Zones Initiative. No president or Congress has ever promised to eliminate poverty; instead, each promised only to improve the system serving the poor or to reduce the number of poor in our society.

Solutions require social action—in the form of social policy, advocacy, and innovation—to address problems at their structural or individual levels. Social policy is the enactment of a course of action through a formal law or program. Policy making usually begins with identification of a problem that should be addressed; then, specific guidelines are developed regarding what should be done to address the problem. Policy directly changes the social structure, particularly how our government, an organization, or our community responds to a social problem. In addition, policy governs the behavior and interaction of individuals, controlling who has access to benefits and aid (Ellis 2003). Social policies are always being enacted. According to Jacob Lew, President Barack Obama’s budget director, “the [federal] budget is not just a collection of numbers, but an expression of our values and aspirations” (as quoted in Herbert 2011:11).

Service and volunteer opportunities are available to college and university students in the United States and abroad. This student is doing her service work in Kingston, Jamaica, through Emory University’s nursing program.

Karen Kasmauski/Getty Images

Social advocates use their resources to support, educate, and empower individuals and their communities. Advocates work to improve social services, change social policies, and mobilize individuals. During his first presidential campaign, Barack Obama recalled his work as a community organizer for the Developing Communities Project in Chicago’s far South Side. The church-based organization served White, Black, and Latino blue-collar neighborhoods addressing education, public safety, and housing issues.

Social innovation may take the form of a policy, a program, or advocacy that features an untested or unique approach. Innovation usually starts at the community level, but it can grow into national and international programming. Millard and Linda Fuller developed the concept of “partnership housing” in 1965, partnering those in need of adequate shelter with community volunteers to build simple interest-free houses. In 1976, the Fullers’ concept became Habitat for Humanity International, a nonprofit, ecumenical Christian housing program responsible for building more than 1 million houses worldwide. When Millard Fuller was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, President Clinton described Habitat for Humanity as “the most successful continuous community service project in the history of the United States” (Habitat for Humanity 2004).

Making Sociological Connections

In his book Social Things: An Introduction to the Sociological Life, Charles Lemert (1997) tells us that sociology is often presented as a thing to be studied. Instead, he argues that sociology is something to be “lived,” becoming a way of life. Lemert (1997) writes,

To use one’s sociological imagination, whether to practical or professional end, is to look at the events in one’s life, to see them for what they truly are, then to figure out how the structures of the wider world make social things the way they are. No one is a sociologist until she does this the best she can. (p. 105)

We can use our sociological imagination, as Lemert (1997) recommends, but we can also take it a step further. As Marx (1972) maintained, “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however is to change it” (p. 107).

Throughout this text, we explore three connections. The first connection is the one between personal troubles and public issues. Each sociological perspective—functionalist, conflict, feminist, and interactionist—highlights how social problems emerge from our social structure or social interaction. While maintaining its primary focus on problems within the United States, this text also addresses the experience of social problems in other countries and nations. The comparative perspective will enhance your understanding of the social problems we experience here.

The sociological imagination will also help us make a second connection: the one between social problems and social solutions. Mills believed that the most important value of sociology was in its potential to enrich and encourage the lives of all individuals (Lemert 1997). In each chapter, we review selected social policies, advocacy programs, and innovative approaches that attempt to address or solve these problems.

Textbooks on this subject present neat individual chapters on a social problem, reviewing the sociological issues and sometimes providing some suggestions about how it can and should be addressed. This book follows the same outline but takes a closer look at community-based approaches, ultimately identifying how you can be part of the solution in your community.

I should warn you that this text will not identify a perfect set of solutions to our social problems. Individual action may be powerless against the social structure. Some individuals or groups will have more power or advantage over others. Solutions, like the problems they address, are embedded within complex interconnected social systems (Fine 2006). Sometimes solutions create other problems. For example, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Chief of Health Mickey Chopra reports that as countries, such as the United States, have focused their attention and funding on the AIDS epidemic worldwide, deaths due to preventable or treatable diseases (e.g., diarrhea and pneumonia) have increased. Diarrhea kills 1.5 million children a year in developing countries, more than AIDS, malaria, and measles combined (Dugger 2009). A program may have worked, but it might no longer exist because of lack of funding or political and public support. Programs and policies are never permanent; they can be modified. Consistent with standards established in many European countries, in 2014 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lifted the prohibition on blood donation from gay and bisexual men, but kept the prohibition in place for men who have had sex with a man in the last year.

In communities such as yours and mine, individuals and community groups are taking action against social problems. They are women, men, and children, common citizens and professionals, from different backgrounds and experiences. Whether they are working within the system or working to change the system, these individuals are part of their community’s solution to a problem. The goal might be to solve one social problem or several or to create what Joel Feagin (2002) describes as a “new global system that reduces injustice, is democratically accountable to all people, offers a decent standard of living for all, and operates in a sustainable relation to earth’s other living systems” (p. 17). As Gary Fine (2006) observes, “those who care about social problems are obligated to use their best knowledge to increase the store of freedom, justice and equality” (p. 14). In the end, I hope you agree that it is important that we continue to do something about the social problems we experience.

In addition, I ask you to make the final connection to social problems and solutions in your community. For this quarter or semester, instead of focusing only on problems reported in your local newspaper or the morning news program, start paying attention to the solutions offered by professionals, leaders, and advocates. Through the Internet or through local programs and agencies, take this opportunity to investigate what social action is taking place in your community. Regardless of whether you define your “community” as your campus, your residential neighborhood, or the city where your college is located, consider what avenues of change can be taken and whether you can be part of that effort.

I often tell my students that the problem with being a sociologist is that my sociological imagination has no “off” switch. In almost everything I read, see, or do, there is some sociological application, a link between my personal experiences and the broader social experience that I share with everyone else, including you. As you progress through this text and your course, I hope that you will begin to use your own sociological imagination and see connections between problems and their solutions that you never saw before.

Young and Homeless

Solving Problems

Sociology at Work

Doing Sociology

At the end of each chapter, the Sociology at Work feature will examine how your sociological imagination and skills can be used in the workplace.

You may be most familiar with how your sociology professors use their sociological imagination as teachers and researchers. Yet sociology is practiced in a variety of ways and settings beyond academia. Hans Zetterberg, in his 1964 article “The Practical Use of Sociological Knowledge,” identified five roles for sociologists: decision maker, educator, commentator/critic, researcher, and consultant. Notice that none of these roles includes sociologist in the title. Yet people are doing sociology, using sociological methods and skills or applying their sociological imagination in their work, even though sociology or sociologist is not part of their job description.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014), many Sociology bachelor’s degree holders find positions in related fields, such as social services, education, or public policy. Based on their survey of recent bachelor’s degree graduates, the American Sociological Association (Spalter-Roth and Van Vooren 2008) reported that about one quarter of full-time working graduates were employed in social service and counseling occupations. Almost 70% of graduates who reported that their jobs were closely related to their Sociology major were very satisfied with their jobs.

In Chapters 2 through 5, we will review how your sociology learning experiences and skill development will be important for your post-college work life. Specific occupations will be examined in Chapters 6 through 15, including social work, criminal justice, public health, education, and medicine. Told through stories of Sociology alumni, these features highlight how sociology can be used in the workplace. In Chapter 16, we’ll discuss opportunities in the global job market, and we’ll conclude with a discussion on postgraduate study in Chapter 17.

Chapter Review

- 1.1 Define the sociological imagination

The sociological imagination is the ability to recognize the links between our personal lives and experiences and our social world.

- 1.2 Identify the characteristics of a social problem

A social problem is a social condition that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or the physical world. A social problem has objective and subjective realities. The identification of a social problem is a process that happens over time.

- 1.3 Compare the four sociological perspectives

A functionalist considers how the social problem emerges from society itself. From a conflict perspective, social problems arise from conflict based upon social class or competing interest groups. By analyzing the situations and lives of women in society, feminist theory defines gender (and sometimes race or social class) as a source of social inequality, group conflict, and social problems. An interactionist focuses on how we use language, words, and symbols to construct and define social problems.

- 1.4 Explain how sociology is a science

Sociologists rely on scientific methods of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analyses to investigate individuals, social processes, and structures.

- 1.5 Explain the roles of social policy, advocacy, and innovation in addressing social problems

Solutions require social action—in the form of social policy, advocacy, and innovation—to address problems at their structural or individual levels. Social policy is the enactment of a course of action through a formal law or program. Social advocates use their resources to support, educate, and empower individuals and their communities. Social innovation may take the form of a policy, a program, or advocacy that features an untested or unique approach. Innovation usually starts at the community level, but can be applied to national and international programming.

Key Terms

- alienation, 14

- anomie, 13

- applied research, 19

- basic research, 19

- bourgeoisie, 14

- class consciousness, 15

- conflict perspective, 14

- dependent variable, 19

- dysfunctions, 14

- feminist perspective, 15

- functionalist perspective, 13

- globalization, 4

- human agency, 17

- hypothesis, 19

- independent variable, 19

- interactionist perspective, 16

- macro level of analysis, 12

- micro level of analysis, 12

- objective reality, 7

- patriarchy, 15

- proletariat, 14

- qualitative methods, 21

- quantitative methods, 20

- social construction of reality, 8

- social constructionism, 8

- social innovation, 23

- social policy, 22

- social problem, 7

- sociological imagination, 5

- sociology, 5

- species being, 14

- subjective reality, 8

- symbolic interactionism, 17

- theory, 12

- variables, 19

Study Questions

- How does the sociological imagination help us understand social problems?

- Select two of the sociological perspectives introduced in this chapter. Compare and contrast how each defines a social problem. What solutions does each perspective offer?

- Identify the objective and subjective realities of the increasing cost of college.

- Apply your sociological imagination to the problem of the increasing cost of college. Is this a personal problem only for students who can’t afford tuition? Or is the increasing cost of tuition a public issue?

- Using the social constructionist perspective, analyze how the primary messages in the 2012 presidential campaign (and leading up to the 2016 campaign) were defined by the candidates, political leaders, the media, and public interest groups. In your opinion, what was defined as a social problem?

- Explain how science and the scientific method help us understand social problems. How is this different from a commonsense understanding of social problems?

- Select two research methods and explain how each could be used to examine the impact of the rising cost of college on students, their families, and the institution of higher education.

- What is the relationship among social advocacy, innovation, and policy?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.