Chapter 17 Social Problems and Social Action

Learning Objectives

- 17.1 Explain the relationship between sociology, social movements, and social change

- 17.2 Distinguish between reform and revolutionary movements

- 17.3 Compare cognitive liberation and collective consciousness

- 17.4 Identify the three areas of change for successful reform movements

In our first chapter, I introduced you to three connections that would be made throughout this text. The first was the connection between sociology and social problems. We began with two concepts offered by C. Wright Mills: personal troubles and public issues. Mills explained that personal troubles transform into public issues when we recognize that troubles exist not because of individual characteristics or traits but because of social forces. This book has not focused on “nuts, sluts, and perverts” (Liazos 1972) as the source of our social problems. Rather, using our sociological imagination, we’ve examined how social forces shape social problems in U.S. society. We have relied on four sociological perspectives—functionalist, conflict, feminist, and interactionist—to guide us through each chapter and each set of problems. These four perspectives provide a unique look at social problems and, as a consequence, offer insights about how we may solve them.

According to a functionalist, all society’s needs are met by its social institutions (family, education, politics, religion, and economics). Working interdependently, these institutions ensure social order. When society experiences significant social change (e.g., the Industrial Revolution, war), the social order is particularly susceptible to social problems (e.g., crime, poverty, or violence). Social problems do not emerge from individuals; rather, problems emerge when the order is disrupted or tested. Functionalist solutions focus on restoring the social order, repairing the broken institutions, and avoiding dramatic social change.

Like the functionalists, conflict and feminist theorists examine social problems at the macro or societal level. For conflict theorists, social problems are the result of social, economic, or political inequalities inherent in our society. Feminist perspectives consider how gender inequalities lead to social problems. Whereas functionalists assume that order is normal for society, the conflict and feminist theorists believe that conflict over resources and power is the status quo. From this perspective, how does one eliminate social problems? The existing social order needs to be replaced with a more equitable society. Midrange solutions attempt to redefine opportunity and power structures to include the participation of marginalized individuals or groups.

The interactionist perspective focuses on social problems at the micro or individual level. According to this perspective, we create our reality through social interaction. Social problems are created by the labels we attach to individuals and their situations (e.g., the “welfare mom” or a “crack addict”). In addition, problematic behavior is learned from others; for example, interactionists believe that criminal behavior is learned from other criminals. Social problems are not objective realities. Rather, they are subjectively constructed by religious, political, and social leaders who influence our opinions and conceptions of what is a social problem. This perspective leads us to many different solutions: changing the labeling process (being careful of who is being labeled and what the label is), resocialization for deviant or inappropriate behavior (if the behavior was learned, it can be unlearned), and recognizing the social construction of social problems (acknowledging that it is a subjective process).

Understanding Social Movements

The past 16 chapters have revealed how we continue to experience many social problems—and bear in mind that not every social problem could be addressed in the pages of this text. Yet, considering the past decade, strong evidence suggests that problems such as crime, drug abuse, and poverty have been minimized because of effective social policies and solutions. We tend to think of the government as the only effective agent of social change because politicians pass new laws and policies. But the government is not the only agent of social change. In each chapter, I introduced you to individuals, groups, and communities that have attempted to address a particular social problem. All in their own way are making the second connection, the one between social problems and their solutions.

Our nation’s history is filled with groups of people who attempted to promote change or prevent it from taking place (Harper and Leicht 2002). Social movements are defined as conscious, collective, organized attempts to bring about or resist large-scale change in the social order (J. Wilson 1973). In today’s society, almost every critical public issue leads to a social movement supporting change (and an opposing countermovement to discourage it) (Meyer and Staggenbord 1996). Social movements are the most potent forces of social change in our society (Sztompka 1994). Social movements lead the way for social reform and policies by first identifying and calling attention to social problems.

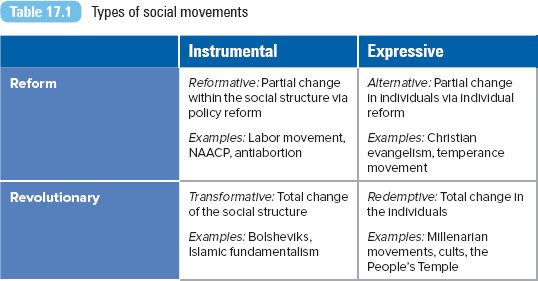

Social movements are classified by two factors. First, how much change is intended by the social movement: is it limited or radical change? And second, what is the scope of the intended change: is it a group of people or an entire society? Sociologists Charles Harper and Kevin Leicht (2002) distinguish between two dimensions of social movements in their book Exploring Social Change: America and the World. The first dimension identifies how much change is intended by the movement, distinguishing between reform and revolutionary movements. According to Harper and Leicht, reform movements try to bring about limited social change by working within the existing system, usually targeting social structures such as education or medicine and directly targeting policy makers. Examples of reform movements are pro-choice or anti-abortion groups. On the other hand, revolutionary social movements seek fundamental changes of the system itself. These types of social movements, such as the U.S. civil rights movement or the antiapartheid movement in South Africa, consider the political system the key to system change.

The second dimension of social movements identified by Harper and Leicht (2002) is instrumental versus expressive, addressing the scope of intended change. Instrumental movements seek to change the structure of society; examples are the civil rights movement and the environmental movement. Expressive movements attempt to change individuals and individual behavior. Based on these dimensions, John Wilson (1973) specified four types of social movements: reformative, transformative, alternative, and redemptive (see Table 17.1).

New social movements theory emphasizes the distinctive features of recent social movements. New social movements first appeared in cultural and radical feminist movements in the late 1960s, in some radical sections of the environmental movement in the 1970s, in parts of the peace movement of the late 1970s through the mid-1980s, and in radical sections of the gay rights movement since the 1980s (Plotke 1995).

John Hannigan (1991) and David Plotke (1995) distinguish between new social movements and early social movements. First, new movements have different ideologies than did earlier movements. Instead of fighting for human rights, such as voting or freedom of speech, new movements are framed around concerns about cultural and community rights, such as the right to be different, to choose one’s lifestyle, and to be protected from particular risks like nuclear or environmental hazards (Hannigan 1991). These movements have been described as identity movements, focused on cultural issues rather than economic or political power. New social movements promote a “more diverse and citizen-oriented set of interests” (Dalton, Kuechler, and Büklin 1990:3). Second, new social movements distrust formal organizations. Consequently, they tend to be small-scale, informal organizations. Finally, whereas previous movements were identified with the economic oppression of workers or minorities, new social movements are associated with a new middle class of “younger, social and cultural specialists” (Plotke 1995). Instead of acting on behalf of their own interests, this new middle class acts on behalf of groups who cannot act on their own.

Racial Women, Embracing Tradition

How Do Social Movements Begin?

Social scientists offer several explanations of how social movements emerge. Individual explanations focus on the psychological dispositions or motivations of those drawn to social movements. Women and men are depicted as either frustrated or calculating actors in political or social movements. Empirical studies have not consistently supported these explanations, demonstrating that individual predispositions are insufficient to account for collective action in social movements. In addition, such theories tend to deflect attention from the real causes of discontent and injustice in our social and political structures (Wilson and Orum 1976).

Social movements do not generally arise from a stable social context; rather, they arise from a changing social order (Lauer 1976). Social movements arise from the structure itself, primarily the result of social and economic deprivation. People are not acting just because of their suffering. They are likely to act when they experience relative deprivation, a perceived gap between what they expect and what they actually get. James Davies (1974) argued that social movements are likely to occur when a long period of economic and social improvement is followed by a period of decline. Relative deprivation theory has been used to explain the development of urban protests among African Americans during the 1960s, which were initiated by middle-class African Americans who perceived social and economic gaps between Black and White Americans (Harper and Leicht 2002). But relative deprivation alone isn’t enough to create a social movement.

Neil Smelser (1963) explains that six structural conditions are necessary for the development of collective behaviors and social movements. These conditions operate in an additive fashion. First, particular structures in society are more likely to generate certain kinds of social movements than others. For example, societies with racial divisions are more likely to develop racial movements. Second, people will become dissatisfied with the current structure only if the structure is perceived as oppressive or illegitimate. Third, there must be growth of a generalized belief system. People need to share an ideology, a set of ideas, that defines the sources of the structural problems or strains and the solutions necessary to alleviate them. The civil rights movement was based on the ideology that racism was the source of restricted opportunities for minorities (Harper and Leicht 2002). Fourth, dramatic events sharpen and concretize issues. These events may initiate or exaggerate people’s dissatisfaction with the current structure or redefine their beliefs about the sources of the structural problems. Examples of dramatic or precipitating events include the 1968 Watts riots in relation to the Black Power phase of the civil rights movement and the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear disaster in relation to the antinuclear power movement (Harper and Leicht 2002). Fifth, the movement gains momentum with the mobilization of leaders and members for the movement. At this time, the social movement also begins to take the shape of a formal organization. Finally, forces in society (the existing political structure or countermovements) respond to the social movement either by accepting or by suppressing it. One of the important features of Smelser’s theory is his emphasis on the relationship between the social movement and society itself, a powerful force in shaping the development, the direction, and, ultimately, the success of the movement (Harper and Leicht 2002).

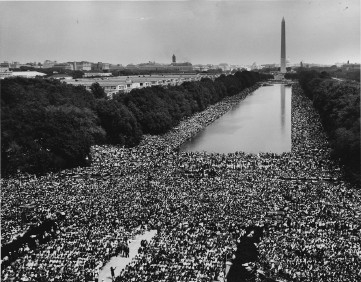

More than 200,000 people participated in the March on Washington demonstrations in March 1963. This march, along with other nonviolent protests and marches, brought to the nation’s attention the need for basic civil rights for all Americans, regardless of race. The U.S. Congress passed landmark legislation in the 1960s: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (also known as the Fair Housing Act).

U.S. Information Agency

According to resource mobilization theory, no social movement can succeed without resources. John McCarthy and Mayer Zald (1977) argue that human and organizational resources must be mobilized to create a social movement. A social movement requires human skills in the form of leadership, talent, and knowledge, as well as an organizational infrastructure to support its work.

On the other hand, the political process model emphasizes the relationship between a mobilized social movement and a favorable structure of political opportunities. Social movements are seen as rational attempts by excluded groups to mobilize their political leverage to advance their interests. Social movements are political phenomena, attempting to change social policy and political coalitions, in this view. Political structures enhance the likelihood of a successful social movement by being receptive to change or by being more or less vulnerable at different points in time. For example, Doug McAdam (1982) noted that the efforts of the civil rights movement were enhanced by the expansion of the Black vote and the shift of Black voters to the Democratic Party. Without favorable support from the political structure, the civil rights movement might not have succeeded.

Social movements gain strength when they develop symbols and a sense of community, which generates strong feelings and helps direct this energy into organized action. People will form a social movement when they develop “a shared understanding of the world and of themselves that legitimate[s] and motivate[s] collective action” (McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald 1996:6). McAdam (1982) explains that resource mobilization must include cognitive liberation. Much like Karl Marx’s concept of class consciousness, cognitive liberation begins when members of an aggrieved group begin to consider their situation as unjust. They must recognize their situation. The second part of cognitive liberation is the group’s sense that its situation can be changed. Finally, those who considered themselves powerless begin to believe that they can make a difference (Piven and Cloward 1979). Individuals must move through all three stages to become cognitively liberated. They must organize, act on political opportunities, and instigate change: “In the absence of these necessary attributions, oppressive conditions are likely, even in the face of increased resources, to go unchallenged” (McAdam 1982:34).

The Occupy Wall Street movement (or Occupy for short) was described as the first worldwide postmodern uprising (Brucato 2012). What began with hundreds of protestors in Zuccotti Park, New York, spread to more than 900 cities globally (Adam 2011) and hundreds of college and university encampments across the United States. The movement had been described as a new model for organizing and protesting: a gathering of multiple groups with diverse issues and causes, developing politics through interaction and participatory structures and lacking a clear beginning and ending (Brucato 2012). Some scholars, like political scientist Sidney Tarrow (2011), noted how Occupy closely mirrored the second wave of feminism. Tarrow writes,

Although the leaders of the new women’s movement had policies they wanted on the agenda, their foremost demand was for recognition of, and credit for, the gendered reality of everyday life. Likewise, when the Occupy Wall Street activists attack Wall Street, it is not capitalism as such they are targeting, but a system of economic relations that has lost its way and failed to serve the public.

While Occupy became “a means of channeling legitimate anger toward productive ends, the progressive transformation of society” (Langman 2013:520), most have dismissed it as a protest, never achieving movement status due to its lack of central leadership, an organizational structure, and a single issue to unite protestors.

Greensboro Lunch Counter Sit-ins

Handbook for Activists

Sermons and Civil Rights

In Focus

Student Activism

College and university students have always played an important role in addressing social problems. According to longtime social activist Ralph Nader (1972), it is up to students “to prod and to provoke, to research and to act” (p. 23). The time in college is a fertile opportunity for social activism (Munson 2010). While at this particular life transition point, students experience significant change in their daily routines and their social networks. Ziad Munson (2010) explains, “To become active in a social movement, people must change their routines to accommodate the demands of activism; they need to incorporate new habits and activities that make them a part of a movement” (p. 774). When social networks are reconfigured, college students are open to new ideas and new worldviews. When regular routines are disrupted, this creates space for (new) social activism.

Student action has led to significant social change. For example, voting drives led by 17- and 18-year olds produced the Twenty-Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, granting voting rights to those 18 years of age and older (Nader 1972). The driving force behind the Twenty-Sixth Amendment came from youth who raised questions about the legitimacy of a representative government that asked 18- to 20-year-olds to fight in the Vietnam War but denied them the right to vote on war-related issues (Close Up Foundation 2004). Norvald Fimreite, a graduate student at the University of Western Ontario, was the first to report unusual levels of mercury residues in fish caught in the Great Lakes (Nader 1972). Fimreite’s data led to a worldwide alert about the problems of mercury and other chemicals in the fish we eat.

Dolores Ramos (right) joined her Highland High School classmates to protest New Mexico’s Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers examination. The standardized exam is part of the new Common Core standards. On their March 2015 exam day, hundreds of high school students left their classrooms and refused to take the exam.

AP Photo/Russell Contreras

Nader believes student activists can accomplish quite a lot:

Take the corporate polluter. Sit-ins and marches will not clean up rivers and the air that he fouls. He is too powerful and there are too many like him. Yet, the student has unique access to resources that can be effective in confronting the polluter. University and college campuses have the means for detecting the precise nature of the industrial effluent, through chemical and biological research. Through research such as they perform every day in the classroom, students can show the effect of the effluent on an entire watershed, and thus alert the community to real and demonstrable dangers to public health—a far more powerful way to arouse public support for a clean environment than a sit-in. Using the expertise of the campus, students can also demonstrate the technological means available for abating the discharge, and thus meet the polluter’s argument that he can do nothing to control his pollution. By drawing on the knowledge of economists, students can counter arguments that an industry will go bankrupt or close down if forced to install pollution controls. Law and political science students can investigate the local, state, or federal regulations that may apply to the case, and publicly challenge the responsible agencies to fulfill their legal duties. p. 21)

How Have Reform Movements Made a Difference?

“The interest of many scholars in social movements stems from their belief that movements represent an important force for social change” (McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald 1988:727); yet, “the study of the consequences of social movements is one of the most neglected topics in literature” (Giugni 1999:xiv–xv). Early in human history, most social change was the result of chance or trial and error (Mannheim 1940), but in modern history, social movements have been the basic avenues by which social change takes place (Harper and Leicht 2002).

According to Harper and Leicht (2002), the most dramatic social, cultural, economic, and political transformations come from revolutions. Successful revolutions are rare and dramatic events, such as the early revolutions in France (1789), Russia (1917), and China (1949), and they include the political transformations in South America, Eastern Europe, and the former Soviet Union during the 1980s.

Most social movements that we’re familiar with are reform movements that focus on either broad or narrow social reforms. They produce significant change, but in gradual or piecemeal ways (Harper and Leicht 2002). The most important U.S. reform movements in the first half of the 20th century focused on grievances related to social class, such as the labor movements of the early 1900s, which helped ensure safer working conditions, eliminated child labor, and provided substantial increases in wages and benefits. After World War II, a new type of reform movement, which included the civil rights movement, the student movement, the feminist movement, the gay liberation movement, and ethnic/racial movements, addressed inequalities based on social status rather than social class (Harper and Leicht 2002). Successful reform movements generate change in three areas:

- Culture. Reform movements educate people and change beliefs and behaviors. Change can occur in our culture, identity, and everyday life (Taylor and Whittier 1995). By changing the ways individuals live, movements may effect long-term changes in society (Meyer 2000). The women’s movement has established a clear record of cultural change. The women’s movement changed the way women viewed themselves and altered our language, our schools, the workplace, politics, the military, and the media.

- New organizations or institutions. Movements lead to the creation of new organizations that continue to generate change. Through these new organizations, social movements may influence ongoing and future initiatives by altering the structure of political support, limiting resources to challengers, and changing the values and symbols used by supporters and challengers. David Meyer (2000) argues that by changing participants’ lives, “movements alter the personnel available for subsequent challenges” (p. 51).

- From the women’s movement, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was created in 1966, along with the Women’s Equity Action League (1968), the National Women’s Political Caucus (1971), the National Women’s Law Center (1972), and the Feminist Majority Foundation (1987). NOW is the largest organization of feminist activists in the United States, with more than 500,000 members and 550 chapters in all 50 states. The organization continues its advocacy and legislative efforts in guaranteeing equal rights for women, ensuring abortion rights and reproductive freedom, opposing racism, and ending violence against women.

- Social policy and legislation. Successful social policies have been nurtured by partnerships between the government and social movements (Skocpol 2000). Movements generally organize and mobilize themselves around specific policy demands (Meyer 2000), attempting to minimize or eliminate social problems. Public policy can do many things: new laws can be enacted or old ones may be struck down, social service programs can be created or ended, and taxes can be used to discourage bad behaviors (cigarette or alcohol taxes) or encourage other behaviors (tax breaks to build enterprise zones) (Loseke 2003).

For reform movements, the relationship between desired and actual change varies (Lauer 1976). So far, the women’s movement has not achieved the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), first proposed in 1923. As of 2012, 35 of the necessary 38 states had ratified the ERA. The women’s movement has made progress in revising laws pertaining to violence against women, creating family-friendly business practices, and enhancing women’s roles in the military, clergy, sports, and politics.

Why Social Movements Should Ignore Social Media

Eve Ensler: Happiness in Body and Soul

Taking a World View

Nongovernmental Organizations as a Source of Change

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have been called a “positive force in domestic and international affairs, working to alleviate poverty, protect human rights, preserve the environment, and provide relief worldwide” (McGann and Johnstone 2006:65). The term refers to private, voluntary, civil society, and nonprofit organizations advocating on behalf of a range of issues: poverty, human rights, the environment, and social justice. NGOs also represent industry associations, religious organizations, and obscure causes (Paul 2000).

NGOs are known for their innovative campaigns and mobilization strategies, especially for their ability to work outside traditional government structures and political networks. Notable NGO activity includes the collection of labor, antiglobalization, and environmental groups that converged on the 1999 World Trade Organization meeting. NGOs exerted their global influence on the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (1992) and Fourth World Conference on Women (1995).

There is no definitive count of the number of domestic and international NGOs. In 2014, there were an estimated 35,000 international NGOs (with programs in multiple countries), an increase from the 400 international NGOs reported in 1900 (Paul 2000). For example, Amnesty International, an activist group campaigning for human rights, has more than 3 million members in 150 countries. The number of NGOs has grown, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, India, and developing countries in Africa and Latin America.

Making the Last Connection

It was a Sunday evening, January 31, 1960, when four freshmen at North Carolina Agriculture and Technical College stayed up late talking about ending segregation in the South. They were extraordinarily poorly positioned to effect political or social change on campus, much less in the United States: young, Black, by no means affluent, and generally disconnected from the major centers of power in America. On Monday morning Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeill, and David Richmond dressed in their best clothes to visit the Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro. After buying some school supplies, they sat at the lunch counter and waited for service. They spent the rest of their day there.

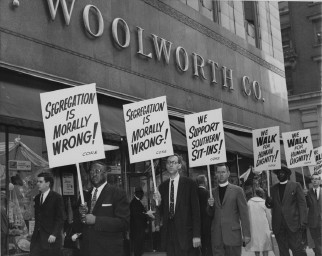

In the 1960s anti-segregation protests expanded beyond the south. In this photo ministers picket in front of New York City’s F.W. Woolworth store to protest lunch counter segregation practices in the company’s southern stores.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, [LC-DIG-ppmsca-08096]

The following day, 27 other Black students joined them and on Wednesday twice as many. By Thursday, a few sympathetic White students from nearby schools had enlisted and, with the lunch counter at Woolworth’s filled, a few started a sit-in at another lunch counter down the street. By the end of the week, city officials offered to negotiate a settlement and, on Saturday night, 1,600 students rallied to celebrate this victory. News of the sit-in campaigns spread throughout the South and then elsewhere across the United States, spurring other activists to emulate their efforts. Sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters and restaurants, stores and libraries, and even buses swept the South. A new organization, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), was formed in April 1960. SNCC would become a leading force in the civil rights movement, setting much of the agenda for liberal politics in the United States during the early 1960s, precipitating the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and politicizing student activists across the United States (Meyer 2000:33).

Yes, solutions to social problems are complex and, as Mills advised, ultimately require attention to large social forces and structures, such as those targeted by social movements. But social movements don’t appear overnight. Social movements begin with individual efforts such as those taken by college students Blair, McCain, McNeill, and Richmond. Grassroots organizations with strong community and local leadership, such as those on the front line of the modern environmental movement, have also proven effective in addressing social problems.

Some may believe that individual efforts don’t amount to much, leading only to short-term solutions or effectively helping one person or one family at a time. But according to David Rayside (1998), the impact of any social movement should be measured over the long term. The isolated effort of thousands of individuals and groups “creates changes in social and political climates, which then enable particular groups to make more specific inroads into public policy and institutional practice” (p. 390).

The last connection presented in this text is the connection between social problems and your community. Throughout the country, college students have affirmed their commitment to community service. In 2006, according to UCLA’s annual survey of entering college freshmen, one in four freshmen surveyed believed that it was important to be involved in their community. About 80% of freshmen had participated in community service during their senior year in high school, and 67% of them believed that they would continue volunteering in college (Engle 2006). High school students are also increasing their involvement in community service. School districts in every state except Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota require community service.

President Obama and Michelle Obama have consistently highlighted the importance of volunteer service and its value for the nation. In 2009, President Obama launched the United We Serve initiative, calling for a “sustained, collaborative and focused effort to promote service as a way of life for all Americans” (Corporation for National and Community Service 2009). In the same year, Congress designated September 11 as the National Day of Service and Remembrance, and Obama signed the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, which tripled the number of intensive service opportunities in the AmeriCorps program from 75,000 positions annually to 250,000 by 2017. Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for more information about how others are politically engaged.

If you think there is nothing that you can do to effect change, you’ve not been paying attention. The first step is to recognize that you can make a difference. Thomas Ehrlich (2000:xxvi) identifies how

a morally and civically responsible individual recognizes him or herself as a member of a larger social fabric and therefore considers social problems to be at least partly his or her own; such an individual is willing to see the moral and social dimensions of issues, to make and justify informed moral and civic judgments and to take action when appropriate.

You do not have to believe in quick fixes, universal solutions, or change to the entire world to solve social problems. You do not have to join a national organization. To begin, you can join other college and university students who have chosen to become personally involved in their community. Most efforts are small and practical, but as one college student says, “I can’t do anything about the theft of nuclear grade weapons materials in Azerbaijan, but I can clean up the local pond, help tutor a troubled kid, or work at a homeless shelter” (Levine and Cureton 1998:36).

What does it take to start making that connection with your community? The second step is to explore opportunities for service on your campus and in your community. Take the chapters in this text or the material presented by your instructor to consider what social problems you are passionate about. Determine what issues you’d like to address and determine what individuals or groups you’d like to serve. Even though you may be in your college community for only four or five years, act as if you’re there for life: take an interest in what happens in your community (Hollender and Catling 1996). Whatever your interests are, you can be sure that there are people and programs in your community who share them. And if they don’t exist, what would it take to create such a program?

The third step is to do what you enjoy doing. When you know what you like, when you know what you can contribute, you will find the right connection. Whatever your talent, your community program will appreciate your contribution. It could be that you are an excellent writer; if so, you could help with a program’s monthly newsletter, develop an informational brochure, or design the program’s website. Do you enjoy working with others? Volunteer to work with clients, to answer phones, or to help at a rally. In addition to providing invaluable service to the program, recognize the experience and skills that you will gain from your efforts.

And what is the final step? Go out and do it. It doesn’t have to last an entire semester or school year; you could just volunteer for a weekend or a day. Change doesn’t happen automatically; it begins with individual action. As Paul Rogat Loeb (1994) explains, the hard questions must come from us:

We need to ask what we want in this nation and why; how should we run our economy, meet human needs, protect the Earth, achieve greater justice? . . . The questions have to come from us, as we reach out to listen and learn, engage fellow citizens who aren’t currently involved, and spur debate in environments that are habitually silent.

Sociologist Michael Burawoy (2004) advocates public sociology,

a sociology that seeks to bring sociology to the publics beyond the academy, promoting dialogue about issues that affect the fate of society, placing the values to which we adhere under a microscope. . . . The variety of publics stretches from our students to the readers of our books, from newspaper columns to interviews, from audiences in local civic groups such as churches or neighborhoods, to social movements we facilitate. The possibilities are endless. (p. 104)

Charles Lemert (1997) reminds us of the most valuable sociological lesson:

Sociology . . . is different for all because each [must] find a way to live in a world that threatens even while it provides. Grace is never cheap. In the end, what remains is that we all have a stake in the world. Like it or not, life is always life together. Social living is the courage to accept what we cannot change in order to do what can be done about the rest. (p. 191)

Put your sociological imagination to work to see where change is possible. Do you have the courage?

Camila Vallejo’s Motivation and Inspiration

Voices in the Community

Camila Vallejo

In May 2011, Chilean high school and college students began participating in coordinated marches, sit-ins, and strikes. Their efforts have included thousands of individuals, in protests described as the largest since the days of the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. The students were mobilized by the Student Confederation of Chile (CONFECH, a group of all the student unions from public and some private universities), and the oldest union, the Student Federation of the University of Chile (FECH) (Goldman 2012). Camila Vallejo, a 23-year-old geography student from the University of Chile, emerged as the most prominent and charismatic leader of the student movement. When the protests began, Vallejo was FECH’s elected president.

The young protestors had one primary issue: education reform. While Chile may have the highest income per capita in the region, it ranks as one of the most unequal countries in the world. According to Francisco Goldman (2012), a university education in Chile is proportionally the most expensive—$3,400 a year for tuition—while the average annual salary for a Chilean citizen is $8,500. Most college students take out bank loans and incur years of debt to pay for their education. While President Sebastián Piñera characterized education as a consumer good, Vallejo and her fellow protestors defined it as a fundamental right, advocating how “the university should be the motor of change in society” (Goldman 2012:23).

The student protests have been credited with the resignation of two education ministers, both ineffectual against the students (Goldman 2012). But what began as a student movement has expanded to other Chilean citizen and worker groups. Vallejo explains, “Something very powerful that has come out of the heart of this movement is that people are really questioning the economic policies of the country. People are not tolerating the way a small number of economic groups benefit from the system” (quoted in Moss Wilson 2012:5). The youth, according to Vallejo, have “revived and dignified politics” (quoted in Franklin 2011a). “It is always the youth that make the first move . . . we don’t have family commitments, this allows us to be freer. We took the first step but we are no longer alone, the older generations are now joining this fight” (Vallejo, quoted in Franklin 2011b).

Camila Vallejo joined protestors in Santiago, Chile, demanding a new national system for secondary education. In 2013, Vallejo was elected as a representative of La Florida, Santiago in the Chilean House of Deputies.

© erlucho/iStock

Vallejo has been honored in other countries (Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States) for her leadership and protest work. In 2013, Vallejo was elected a member of the Chilean congress, winning 44% of the vote in the Santiago district of La Florida. She ran as a member of the Communist Party.

Exploring Social Problems

Who Is Politically Engaged?

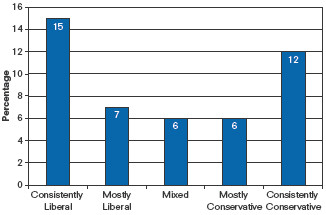

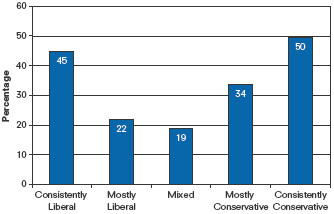

Figure 17.1 Percentage who worked or volunteered for a campaign or candidate, by political ideology, 2014

SOURCE: Pew Research Center 2014.

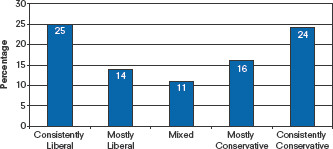

Figure 17.2 Percentage who contacted an elected official, by political ideology, 2014

SOURCE: Pew Research Center 2014.

Figure 17.3 Percentage who attended a campaign event, by political ideology, 2014

SOURCE: Pew Research Center 2014.

What Do You Think?

The Pew Research Center surveyed 10,013 adults in 2014, asking about their political engagement. Political engagement may be operationalized in many different ways—voting, contributing to a candidate, working for a campaign, or attending a political rally.

The Pew researchers concluded that engagement tends to be a U-shaped pattern, with higher levels of engagement at the right and left of the ideological spectrum and lower levels in the center. Notice this pattern in Figures 17.1 through 17.3.

The researchers acknowledge that other factors are correlated with political engagement, such as age and education. Hypothesize the relationship between these other demographic factors and political engagement. As education increases, does the likelihood of political engagement increase or decrease? Explain the reason for your answers.

Sociology at Work

Graduate Study

Barbara Prince–Class of 2012

Undergraduate Majors:

Sociology, Anthropology

Undergraduate Minor: Art History

A master’s or doctorate degree in Sociology is essential for employment in higher education, industry, government, or other nonprofit or research settings.

There are two types of master’s degree programs. The first type is a traditional program that leads to a PhD in Sociology, with a primary career emphasis on academic employment. Most PhD programs also offer a master’s degree track. The second type is a professional or applied program that prepares graduates for research, policy, management, and service occupations. These programs are also referred to as terminal degree programs, as there is no expectation to progress to a PhD program (Spalter-Roth and Van Vooren 2011). Master’s programs usually take two to three years and may include a culminating independent project or a thesis as part of the degree requirement.

A doctorate in philosophy (PhD) is the highest degree awarded in Sociology. A PhD program requires at least five to six years of study beyond the bachelor’s degree. According to the American Sociological Association, over 200 colleges and universities offer PhD programs. A program application usually requires an undergraduate transcript, a personal statement on why you are interested in pursuing doctoral work, faculty recommendations, and scores from the Graduate Record Examination (GRE).

Courtesy of Barbara Prince

Once you decide to pursue graduate work in sociology, work with your adviser to identify which path—master’s or PhD—is for you. Barbara Prince declared her sociology major in her sophomore year, yet knew nothing about careers in sociology. “I just knew that I loved the topics and found the field very interesting. I did know about going to graduate school by the end of my sophomore year, though, because it was something my mentor was always mentioning and very supportive of me pursuing.” In her senior year, Barbara worked as an intern for her mentor. The experience, says Barbara, “was designed to expose me to what I would call the invisible work of being a professor. For example, my responsibilities included helping organize a conference, preparing class and review materials, and assisting with grant writing and execution.”

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Sociology and Anthropology, Barbara earned a master’s degree in Sociology and is currently enrolled in a PhD program.

I am always using sociology at work in the literal sense since I am working as a graduate research assistant in sociology.... I am engaging my sociological imagination to help form my research questions and what I am interested in researching. My sociological imagination also helps me as a graduate research assistant and student to explore alternative explanations for social problems.

For those who are planning to go to graduate school, Barbara offers straightforward advice: “Start planning early, make as many connections as you can, and find a champion mentor.” And for those on the job market, she recommends, “Be unapologetic about your sociology major. The skills you learn in sociology, such as the sociological imagination and critical thinking, are what all jobs are looking for in an employee. Even if someone doesn’t know what sociology is, I guarantee they want what sociology teaches.”

Chapter Review

- 17.1 Explain the relationship between sociology, social movements, and social change

Sociology provides us with the means to examine the social structure or “machinery” that runs our lives. Social movements are conscious, collective, organized attempts to bring about or resist large-scale change in the social order. They are the most potent forces of social change in our society.

- 17.2 Distinguish between reform and revolutionary movements

Social movements are classified by two factors: the scope and the depth of change. Instrumental movements seek to change the structure of society itself, whereas expressive movements attempt to change individuals. While reform movements try to bring about limited social change by working within the existing system, revolutionary social movements seek fundamental changes of the system itself.

- 17.3 Compare cognitive liberation and collective consciousness

Like Marx’s theory of collective consciousness, cognitive liberation begins only when members of an aggrieved group start to consider their situation unjust, to believe the situation can be changed, and to believe they can make a difference. For Marx, collective consciousness eventually leads to social revolution, a transformation of the social structure.

- 17.4 Identify the three areas of change for successful reform movements

Reform movements educate people and change our culture, our beliefs and behaviors. Movements lead to the creation of new organizations that continue to generate change. Movements generally organize and mobilize themselves around specific policy demands, at tempting to minimize or eliminate social problems.

Key Terms

- cognitive liberation, 497

- expressive movements, 493

- instrumental movements, 493

- new social movements theory, 493

- political process model, 497

- public sociology, 506

- reform movements, 493

- relative deprivation, 496

- resource mobilization theory, 497

- revolutionary social

- movements, 493

- social movements, 493

Study Questions

- How does each sociological perspective identify the potential and sources for social change?

- Identify and explain the four dimensions of social movements.

- What is meant by the following statement: “Social movements arise from the structure itself, primarily the result of social and economic deprivation”?

- Explain the relationship between cognitive liberation and social movements.

- Successful reform movements generate change in three areas. Identify and explain these three areas of change.

- Would you characterize the Occupy movement as a social movement? Why or why not?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.