Chapter 16 War and Terrorism

Learning Objectives

- 16.1 Explain the difference between war and terrorism

- 16.2 Explain how the different sociological perspectives examine social problems related to war and terrorism

- 16.3 Define the politics of fear

- 16.4 Identify the effects of war and terrorism

- 16.5 Assess the effectiveness of economic sanctions

The secure life that many Americans took for granted changed on the morning of September 11, 2001 (Hoge and Rose 2001); we now live in a subtly different country (Danner 2011). It is a country whose public and political discourse has been preoccupied with war, terrorism, suicide bombs, torture, patriotism, and human loss. There is an awareness of war and terrorism in other countries and ultimately concern over whether these conflicts will threaten U.S. national security. Sociologists acknowledge that “war is never an isolated act” (Clausweitz 1984:78) and that the consequences are felt and experienced beyond specific battlefields and borders.

A decade after 9/11, a wave of revolutionary demonstrations and protests swept across the Arab world. It began in Tunisia on December 17, 2010, when a police officer took away Mohamed Bouazizi’s vegetable cart because Bouazizi didn’t have a license to sell his goods. After his confrontation with the police and after local officials refused to hear his complaint, Bouazizi set himself on fire in front of the provincial headquarters. Bouazizi’s martyrdom spurred a “people’s revolution” (Abouzeid 2011). Tunisians took to the streets in protest, ultimately leading to the end of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s authoritarian rule. The Arab Spring extended to other countries where citizens participated in public demonstrations, some relatively peaceful, to protest the hardships and cruelties under ruling regimes. Ruling governments were overthrown in Egypt, Libya, and Yemen.

Revolutionary demonstrations and protests continued into 2014. On September 26, hundreds of students gathered in central Hong Kong, demanding an end to Chinese oppression and control. These protests have been referred to as the Umbrella Revolution, after the umbrellas used by protesters to shield themselves from tear gas and later as shelter from the pouring rain. Forced to disband by the end of the year, the student protestors vowed to continue their antigovernment campaign. In sharp contrast, the Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) made headlines in the same year for releasing graphic video of the beheading of foreign captives, including U.S. journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff and U.S. aid worker Peter Kassig. Formerly al-Qaeda in Iraq, ISIS has become known for its brutal and brazen tactics. President Obama pledged to degrade and ultimately destroy ISIS.

Defining Conflict

War

War is a violent political instrument (Walter 1964). It is a violent activity between armed combatants, one side hoping to impose its will on the other. Whether or not war has been declared by its leadership, war involves armed conflict between two or more states or military forces. The majority of today’s wars are civil wars (fought within, not between, countries), and most often, they take place in the poorest countries.

The United Kingdom, France, and Russia have fought the most international armed conflicts since the end of World War II (refer to Table 16.1). The most conflict-prone countries (including civil wars) have been Myanmar (also known as Burma), India, and Ethiopia (Human Security Report Project 2011).

SOURCE: Human Security Report Project 2011.

Since 1945, there have been 140 civil wars throughout the world, killing approximately 20 million people and displacing about 67 million. Civil wars typically occur in developing countries and are fought by small, poorly trained, poorly armed forces that avoid major military engagements, but frequently target civilians (Human Security Report Project 2005). Genocide (the systematic targeting of ethnic or religious groups) and politicide (targeting specific groups because of their political beliefs) have been part of many civil wars. In the competition for political power and economic resources, ethno-political conflict and violence were at the heart of the wars in Cambodia (1977–1979), Rwanda (1994), Somalia (1991–2000), and Western Sudan (2003–present). In 1994, 800,000 Tutsis were massacred by the majority Hutu ethnic group in Rwanda.

The Rise of ISIS

U.S. Conflicts

“The United States was born of violence and revolution,” writes Ken Cunningham (2004), “violence against the native population and among and against the various European imperial powers” (p. 556). Our nation’s birth was marked by a war—the American Revolution of 1775 to 1783. In 1776, the Declaration of Independence was adopted, a public statement of a new nation’s independence from Great Britain and its rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The British were defeated in 1783. More than 4,000 lives were lost in the revolution against the British.

More than 3 million Americans fought in the Civil War (1861–1865). The bloodiest battle on U.S. soil led to more than 600,000 casualties, about 2 percent of the Northern and Southern population at the time.

© HultonArchive/iStock

The American Revolution was followed by the War of 1812 (1812–1815) and the Mexican War (1846–1848), both part of the economic and continental expansion of the United States. The effort was justified under the principle of manifest destiny. U.S. leaders felt it was their mission to extend freedom and democracy to others. At the end of the Mexican War, the United States acquired the northern part of Mexico, later dividing the area into Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. A revolution constitutes an overthrow of the existing government or political structure. Revolutions do not always lead to violent conflict.

The Civil War (1861–1865) between northern and southern states has been referred to as the bloodiest battle on U.S. soil. Although we tend to think that the war was waged solely over the issue of slavery, it was also based on deep economic, political, and social differences between the two groups of states. During his second inaugural address in 1865, President Abraham Lincoln said, “One of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.” More than 600,000 died.

Beginning with the Spanish–American War (1898), U.S. troops and soldiers began to wage war in other countries, mostly responding to tyranny, oppression, and communism. The Spanish–American War was fought to liberate Cuba from Spain and to protect U.S. interests in Cuban sugar, tobacco, and iron industries. U.S. participation during World War I (1917–1918) and World War II (1940–1945) helped establish its dominance as a worldwide military force. That accomplishment, however, came at a great cost: the United States had heavy losses, 53,000 deaths in World War I and 400,000 deaths in World War II. In the latter war, the United States and its allies claimed victory against Germany, Japan, and Italy. After the North Korean People’s Army invaded the Republic of Korea, the United States joined UN forces in the Korean War (1950–1953). No winner of the war has ever been declared. An armistice was agreed upon in 1953, forever separating North and South Korea. Fifty years after the invasion, Communist and UN soldiers still guard their sides of the demilitarized zone in Panmunjom. The United States fought against North Vietnamese Communists in the jungles of South Vietnam from 1964 to 1973. Although U.S. troops had begun withdrawing from Vietnam in 1969, the formal cease-fire was declared in January 1973.

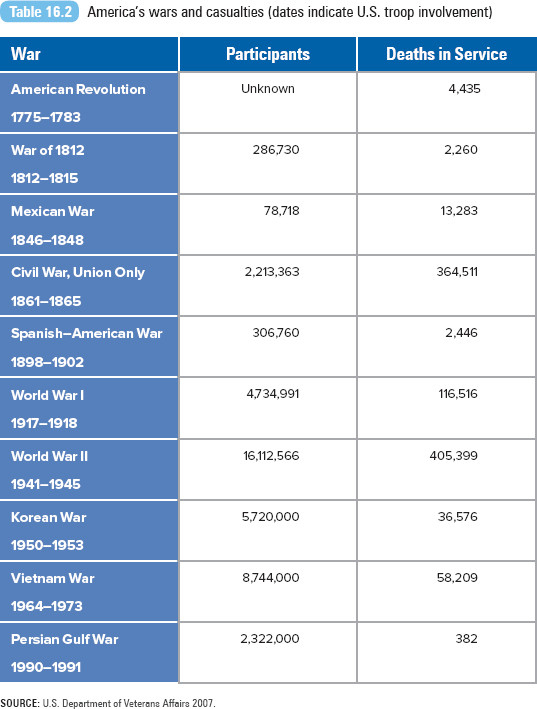

U.S. engagement in Middle East wars began with the Persian Gulf War of 1990 to 1991. The United States was joined by UN forces to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi forces. Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm were the first display of high-tech warfare: cruise missiles, stealth fighters, and precision-guided munitions. Iraq accepted the terms for the cease-fire in April 1991. After September 11, 2001, U.S. forces attacked Afghanistan in an effort to destroy al-Qaeda forces and to locate their leader, Osama bin Laden. The first war of the 21st century was the U.S. war against Iraq (2003–2011) and Afghanistan (2003–2014). Though the U.S. combat mission in Afghanistan officially ended in 2014, a new phase of U.S. military operations was established in 2015. More than 9,000 U.S. troops support the NATO-led Resolute Support Mission to combat-train, advise, and assist Afghan national security forces (White House 2014). As of December 11, 2014, the number of reported military casualties (killed in action or non-hostile deaths) was 4,425 for Operation Iraqi Freedom and 2,354 for Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. A listing of U.S. wars and casualties is presented in Table 16.2. The list does not include the numerous American Indian Wars, the conflicts between American settlers and the U.S. federal government and the indigenous populations of North America.

Terrorism

Terrorism is a specific form of conflict. According to the U.S. federal code, terrorism is “the unlawful use of force or violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives” (28 C.F.R. Section 0.85). Todd Sandler (2011) offers the following definition of terrorism: “the premeditated use or threat to use violence by individuals or subnational groups to obtain political or social objectives through the intimidation of a large audience beyond that of the immediate victims” (p. 280).

Political terrorism expert Grant Wardlaw (1988) states, “Terrorism is a phenomenon that is increasingly coming to dominate our lives.” The effects of terrorism are widespread:

It influences the way governments conduct their foreign policy and corporations transact their business. It causes changes to the structure and role of our security forces and necessitates huge expenditures on measures to protect public figures, vital installations, citizens and perhaps in the final analysis, our system of government. It affects the way we travel, the places we visit and the manner in which we live our daily lives. (Wardlaw 1988:206)

Domestic terrorism is defined as terrorism supported or coordinated by groups or individuals based in a country. The venue and targets are also in the same country. Domestic terrorist groups are likely to be found in large countries and are found more often in democracies than in authoritarian states (Human Security Report Project 2005). International terrorism is defined as terrorism supported or coordinated by foreign groups threatening the security of another nation or its citizens. For example, international terrorism can occur outside the United States but may be directed at U.S. targets. Acts of terrorism have occurred on every continent, and perpetrators come from diverse religious and ethnic groups; however, Islamic governments and networks have committed the most extreme acts of terror (Booth and Dunne 2002). Though in terms of the number killed, international terrorism poses far less of a threat than do other forms of political violence or violent crime, it is an important human security issue (Human Security Report Project 2005). Al-Qaeda and ISIS have come to symbolize terrorism in the 21st century.

Paul Pillar (2001) explains that there are five elements of terrorism: First, terrorism is a premeditated act. It requires intent and prior decision to commit an act of terrorism. Terrorism doesn’t happen by accident; rather, it is the result of an individual’s or a group’s policy or decision. Second, terrorism is purposeful; it is political in its motive to change or challenge the status quo. Religiously oriented or national terrorists are driven by social forces or shaped by circumstances specific to their particular religious or nationalistic experiences (Reich 1998). According to Max Abrahms (2012), terrorist groups have process and outcome goals. Process goals are aimed to sustain the group and its activities by securing financial support, gaining media attention, and boosting group morale. Outcome goals are the group’s stated political ends, which require the cooperation of the target authority or government. Third, terrorism is not like a war in which both sides can shoot at one another. Terrorism targets noncombatants, such as civilians who cannot defend themselves against the violence. The direct targets of terrorist activity are not the main targets. Fourth, terrorism is usually carried out by subnational groups or clandestine agents. If uniformed military soldiers attack a group, it is considered an act of war; an attack conducted by nongovernmental perpetrators is considered terrorism. Individuals acting alone may also commit terrorism. Finally, terrorism includes the threat of violence. It does not involve only terrorist acts that may have occurred; it also involves the potential for future attacks.

Terrorist activity has changed little over the years. Six basic tactics account for 95% of all incidents: bombings, assassinations, armed assaults, kidnappings, hijackings, and other kinds of hostage seizures. As Brian Jenkins (1988) states, “terrorists blow up things, kill people, or seize hostages. Every terrorist attack is merely a variation on these three activities” (p. 257).

Sociological Perspectives on War and Terrorism

Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists examine how conflicts help maintain the social order, creating and reinforcing social, religious, or national boundaries. War creates social stability by letting everyone know what side they are on: the good guys versus the bad guys or us versus them. There are norms and boundaries in war: Individuals will know what their roles are, what they should believe in, how they should respond in case of an attack, and how they should interact with members of the other side. But unlike war, the social boundaries in terrorist activities are less certain. In some cases, the identity of terrorists and their goals may never be known.

War provides a “safety valve” function, giving marginalized or oppressed groups a means to express their discontent or anger. Acts of terrorism, according to Martha Crenshaw (1998), are selected as a course of action from a range of alternatives. Groups may choose terrorism because the other methods may be expected not to work or may be too time-consuming for the group. Radical groups choose terrorism when they want immediate action and when they want their message to be heard. As they act, they spread their group’s message, strengthening the social bonds between group members while recruiting new members for their cause.

The social structure contributes to conflict. For example, a country’s education and age structure are demographic characteristics that help us understand the current situation in the Greater Middle East (Spindel 2011). Educational attainment in these countries is rising, and as a result, so are citizen demands and expectations for resolving the countries’ social problems. The age structure of the population has been identified as a central component in the Arab Spring. Unlike in Western countries, the majority of residents are under 25 years of age—52% in Egypt, 55.2% in Syria, and 54.4% in Jordan. In Germany, 25% of the population is under 25 years of age.

Finally, warfare establishes power and domination. The victor is able to acquire the “spoils of war”—a country’s land, people, and resources. Beyond those tangible fruits of victory, the winning side gets to make new rules or impose its rules about appropriate political, social, and economic structures.

Conflict Perspective

From this perspective, war is not natural; it is a product of oppression and domination. Conflict may be based on disputes over resources or land. Modern conflict theorists have focused on how war is used to promote economic and political interests. In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower cautioned the nation about the military-industrial complex, the growing collaboration of the government, the military, and the armament industry. Years earlier, Eisenhower (1953) warned,

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies in the final sense a theft of those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. The world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.

He explained that the complex had a corrupting influence—economic, political, and spiritual—in every city, state, and federal office of government. A decision to go to war could be motivated not by ideals to preserve or promote freedom, but to ensure the economic well-being of the defense contractor. For example, during the Iraq war, the role of oil services firm Halliburton and its subsidiary company, KBR, was closely scrutinized. Critics identify that Halliburton had an unfair advantage with no-bid military contracting because of its relationship with Vice President Dick Cheney. Cheney served as Halliburton’s CEO from 1996 to 1998 and briefly in 2000. In 2007, federal investigators alleged that Halliburton was responsible for $2.7 billion in contractor waste and overcharging in Iraq.

Social scientists have noted the far-reaching and devastating impact of U.S. militarism for Americans and the rest of the world. Cunningham (2004) identifies a “vast, entrenched, bureaucratic national security apparatus” that reaches into all areas of American life and politics, including businesses, universities, primary and secondary schools, the media, and popular culture. U.S. militarism also reaches into foreign countries, through its direct military intervention and war and covert operations (conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], the National Security Agency [NSA], and other agencies).

Feminist Perspective

From this perspective, war is considered a primarily male activity that enhances the position of males in society. “War is a patriarchal tool always used by men to create new structures of dominance and to subjugate a large mass of people” (“The Events” 2002:96). In our military system, decision-making and economic power are held primarily by men; as a result, international relations and politics are played out on women’s bodies (Cuomo 1996). According to Cynthia Enloe (1990), local and global sexual politics shape and are shaped through the presence of national and international U.S. military bases—through the symbolism of the U.S. soldier, the reproduction of family structures on bases, and systems of prostitution that coexist alongside bases. As she explains, “bases are artificial societies created out of unequal relations between men and women of different races and classes” (Enloe 1990:2).

In 2013, the Pentagon removed its ban on women serving in combat. Full implementation is expected by January 2016.

Reuters/STR New

Men reserve the right to make war themselves and claim that they fight wars to protect vulnerable people, such as women and children, who are viewed as not being able to protect themselves (Tickner 2002). During wars, women are charged with caring for their husbands, their sons, and the victims of war. The ideal of the “caretaking woman” helps exclude women from public and political institutions by reminding them that their first responsibility is to the family. According to Laura Kaplan (1994), this ideal “helps co-opt women’s resistance to the war by convincing women that their immediate responsibility to ameliorate the effects of war takes precedence over organized public action against war” (p. 131).

Communication scholar Mary Douglas Vavrus (2013) examined the gendered propaganda in Lifetime’s drama Army Wives. The popular program aired from 2007 to 2013, depicting the stories of four Army wives and one Army husband whose family members were deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq. Through a feminist analysis of 81 episodes, Douglas Vavrus documented a pervasive message of militarism and gendered labor; “first, that soldiers are fighting over there to protect us, over here . . . second, that wives properly bear the responsibility for the home front while their husbands are deployed to other lands” (p. 98). The women in the program have a feminine approach to the war—building schools or leading medical missions—while their husbands are risking their lives in military missions. The wives were portrayed as long-suffering, supportive, and patriotic. “For the mothers and spouses on the program, standing in the way of either their children or their deploying husbands and wives—either to complain or worry visibly—is to prevent children and spouses from reaching their heroic self-actualization that awaits each soldier in theater” (p. 99).

Women in the Military

Interactionist Perspective

Interactionists focus on the social messages and meaning of war and conflict. Terrorism is a word with intrinsically negative connotations. According to political scientist Crenshaw (1995), the word “projects images, communicates messages, and creates myths that transcend historical circumstances and motivate future generations” (p. 12). In addition, the concept serves as “an organizing concept that both describes the phenomenon as it exists and offers a moral judgment” (Crenshaw 1995:9). As Jenkins (1980) explains,

what is called terrorism thus seems to be dependent on one’s point of view. Use of the term implies a moral judgment; and if one party can successfully attach the label terrorist to its opponent, then it has indirectly persuaded others to adopt its moral viewpoint. (p. 10)

Crenshaw (1995) cautions that once political concepts such as terrorism are constructed, “they take on a certain autonomy, especially when they are adopted by news media, disseminated to the public, and integrated into a general context of norms and values” (p. 9). Use of the word terrorism promotes condemnation of the actors and may reflect an ideological or political bias (Gibbs 1989). Terrorism is a social construct.

Terrorism is particularly useful for agenda setting (Crenshaw 1998) by the terrorist group and its target. If the reasons behind the violence are articulated clearly, terrorists can put their issues on the public agenda. Instantly, the public is aware of the group and its cause. The act may make some sympathetic to the group or could elicit anger and calls for retaliation. But the target—such as the U.S. government—can also use terrorism to set its own agenda. According to Crenshaw (1998), “conceptions of terrorism affect the ways in which governments define their interests, and also determine reliance on labels or their abandonment when politically convenient” (p. 10). When the problem is labeled terrorism or a group is labeled terrorists, a set of predetermined preferred solutions begins to emerge. When these terms depict the group as “fanatical and irrational,” making attempts at diplomacy or compromise seem impossible, the inference is that the U.S. government has nothing left to do but retaliate with force. But the labeling doesn’t stop: such defensive actions are often “appropriate” and “legitimate” expressions of “self-defense,” but not “terrorism.”

David Altheide (2006) explains how decision makers and politicians promote and use the public’s beliefs and assumptions about terrorism to achieve certain goals. He refers to this as the politics of fear. The politics of fear promotes attacking a target, limits civil liberties, and anticipates further victimization. Altheide warns how fear promotes fear, changing our behavior and perspective. Sarah Oates (2006), in her analysis of the role of terrorism coverage in the 2004 presidential/parliamentary election campaigns in Russia, Great Britain, and the United States, concluded that terrorism played an emotive role for American and Russian voters. American and Russian voters identified terrorism as the most important issue in the election, leading them to vote for the candidate they perceived as “stronger” against the threat of terrorism, regardless of the candidate’s specific policies or political views. Oates reported that terrorism did not play a role in the Great Britain election, as it was mentioned in only 10% of all British news segments in her sample, whereas it was mentioned in 25% of all U.S. election news segments. In Great Britain, the primary issues were the lack of public support for the country’s involvement in the Iraq war and the state of Great Britain’s economy. For more about the fear of terrorism, refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature.

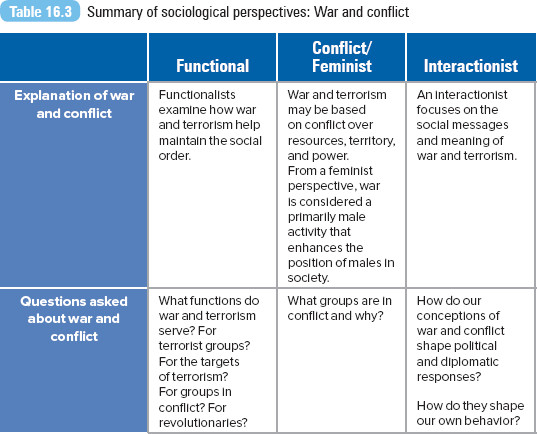

For a summary of sociological perspectives, see Table 16.3.

Exploring Social Problems

The Fear of Terrorism

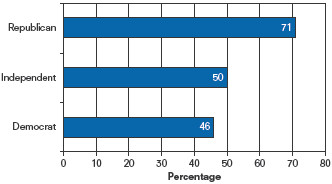

Figure 16.1 Percentage very concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in the United States, by political party affiliation

SOURCE: Adapted from Pew Research Center 2014.

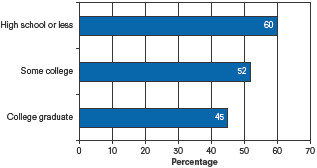

Figure 16.2 Percentage very concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in the United States, by educational attainment

SOURCE: Adapted from Pew Research Center 2014.

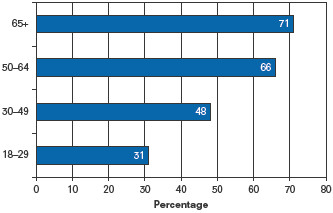

Figure 16.3 Percentage very concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism in the United States, by age

SOURCE: Adapted from Pew Research Center 2014.

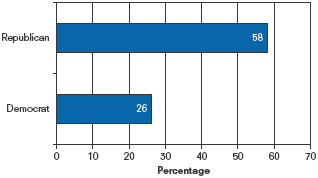

Figure 16.4 Percentage who believe government is doing not too/not at all well in reducing the threat of terrorism, by political party affiliation, 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from Pew Research Center 2014.

What Do You Think?

During the 2014 midterm congressional elections, voters identified their primary concern as the state of our national security and our defenses against Islamic terrorism. The Pew Research Center conducted a national poll, asking Americans to report how concerned they were about the threat of Islamic extremism reaching the United States. Poll results are presented in Figures 16.1 to 16.3, summarizing concern by political party affiliation, education, and age.

Based on these figures, who is most concerned about Islamic terrorism?

Note how public opinion on whether the government is not doing enough to reduce the threat is also divided by political party affiliation (Figure 16.4).

Using your sociological imagination, why are these groups most concerned about terrorism? How might the politics of fear play a role in their perceptions about terrorism?

The Problems of War and Terrorism

The Impact of War and Terrorism

Psychological Impact

According to Crenshaw (1983), small incremental societal changes in trust, social cohesion, and integration occur as a result of terrorism. Terrorism has a particular impact in small or homogeneous societies. Research on the long-term impact of terrorism is limited, although some case studies have been conducted in Northern Ireland, where residents have lived with domestic terrorism since the late 1960s. (See this chapter’s Taking a World View discussion for more about the Irish Republican Army [IRA].)

War takes a psychological toll, particularly for soldiers involved in battle. Mental health experts have identified posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a common aftereffect of battle. Those suffering from PTSD feel depressed and detached and have nightmares and flashbacks of their war experience. This anxiety disorder may occur with related issues, such as depression, substance abuse, cognition problems, and other problems of physical or mental health (National Center for PTSD 2003a). About 7% to 8% of the general U.S. population will experience PTSD symptoms in their lifetimes.

Vietnam veterans were particularly hard-hit because of extensive war-related trauma: serving hazardous duty, witnessing death and harm to self or others, and being on frequent or prolonged combat missions. The estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among Vietnam veterans is 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women. An additional 22.5% of men and 21.2% of women have had partial PTSD sometime in their lives (National Center for PTSD 2003b).

It is estimated that between 11% and 20% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans will have PTSD. These service members are also at risk for depression, excessive drinking, and violence (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs 2014a). Based on a national survey of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the Washington Post-Kaiser Family

Foundation found that 52% say their physical or mental health is worse than before the wars. Forty-one percent experience outbursts of anger. More than half of those surveyed reported knowing a service member who has attempted or committed suicide (Clement 2014).

The rate of suicide among these veterans has been described as an epidemic, prompting legislation and funding for programs to address PTSD and other mental illness among the veterans. Much of the response was due to the release of a 2012 Department of Veterans Affairs study that estimated that 22 veterans kill themselves every day. The 22-veterans statistic has been challenged by scholars and journalists, who argue that the department included suicide among veterans who did not serve in the recent conflicts, thus overestimating the number and rate of suicides.

For information on the Iraq war’s impact on veterans, turn to this chapter’s In Focus feature.

FRONTLINE’s “A Soldier’s Heart”

Economic Impact

President George W. Bush pledged that the United States would win the fight against terrorism, “whatever it takes, whatever it costs.” Although the United States now has a smaller army and is using technologies that are less human intensive, military expenditures have been increasing, and with those increases comes the greater likelihood of waste, inefficiency, and “good old fashioned pork,” according to opponents (Knickerbocker 2002).

Marine Cpl. Larry Bailey II (pictured here with his father Larry) is recovering from injuries he received after tripping a rooftop bomb in Afghanistan. Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans are able to survive wounds that in past wars would have been fatal.

AP Photo/Charles Dharapak

The final cost of the Iraq war is estimated to be more than $2 trillion (and unlike past U.S. wars, the Iraq war is being paid almost entirely with debt). The expenditures have been justified as necessary to maintain a high state of military readiness and ground force strength, enhance the combat capabilities of U.S. armed forces, continue the development of capabilities to maintain U.S. superiority against potential threats, and continue the department’s support of service members and their families. Though some believe that these additional defense expenses are necessary to win the global war on terrorism, others have criticized the escalation in military expenditures.

In 2002, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) guaranteed two years of free care to returning combat veterans for any combat-related medical condition. The cost of these benefits, as well as that of providing long-term disability support for soldiers and veterans and their families, may strain the department’s budget and government resources. Policy analysts blame the lack of planning by the VA, noting that the administration did not expect the conflict to last as long as it has and did not predict the nature and extent of mental and physical injuries for its active-duty and retired personnel (Donn and Hefling 2007). In 2014, an internal VA audit revealed that more than 100,000 veterans received inadequate medical care or no care at all in several veteran health facilities across the country. Top VA administrators resigned, and President Obama signed a bill to reform the VA system. Between 2001 and 2013, the U.S. spent $23.6 billion for medical care and $28.9 billion for disability benefits for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans (Bilmes 2013).

A comparison of U.S. war expenditures with other countries is presented in Table 16.4.

Do you recall President Eisenhower’s warning? Billions of dollars spent on the war means that other programs are not receiving any funding. The National Priorities Project, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, analyzes the impact of federal spending policies on city and state funding and budgets. Since the beginning of the Iraq war, the project has tracked the expanding war budget along with increasing budget cuts in nonsecurity (nonwar) discretionary spending. Based on its 2008 budget, the Bush administration proposed cutting $13 billion from social service and education programming—for example, a 35% budget cut in Community Development Block Grants, a 6% cut in the Head Start program, a 40% cut in the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, and 6% in special education programming. At the same time, the administration requested an additional $100 billion for war-related spending (National Priorities Project 2007).

The Budget Control Act of 2011 mandates reductions in federal spending, including defense spending. In 2012, President Obama and Defense Secretary Leon Panetta announced a new strategic military plan and the goal to reduce the budget by $259 billion over the next decade.

The Hidden Cost of the Iraq War

In Focus

The Hidden Costs of War

Of the 2.5 million U.S. forces deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan, almost half have sought care and assistance from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Government, health, and veterans service administrators have observed how different the needs of Iraq war veterans are from those of veterans of past wars and conflicts.

Because of the nature of the conflict itself, forces deployed in Iraq have had more contact with the enemy and more exposure to terrorist attacks than did troops in the earlier Iraq war (O’Connor 2004). The frequency and intensity of operations for active and reserve members increased during the height of the recent wars, with multiple deployments and overseas assignments for soldiers. Estimates range from one in six to one in three soldiers and Marines seeking help for mental health problems or PTSD as a result of their Iraq experiences. Between 80% and 85% of military personnel have witnessed or been part of traumatic events (Vedantam 2006).

About 280,000 female soldiers, Marines, and airmen have been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan (Chandrasekaran 2014), 11% of the overall force. The U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (2014b) estimates that 20% of women Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have been diagnosed with PTSD. Research on this population has indicated higher rates of PTSD and depression for female compared with male veterans, higher incidences of sexual trauma, and lower rates of accessing health care services (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs 2012). At the release of its 2012 report on sexual assault in the military, the Department of Defense was criticized for failing to protect its female soldiers. In 2012, there were 26,000 cases of unwanted sexual contact. Sexual trauma can have adverse ramifications on a veteran’s quality of life, negatively impacting physical health, psychological well-being, employment, and interpersonal relationships. President Obama requested a comprehensive review of the department’s prevention practices and response protocols to sexual assault. After implementing support, education, and training programs and improving accountability measures, the number of cases declined to 19,000 in 2014.

More wounded soldiers are returning home alive from Iraq. In the past, many would not have survived traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) as a result of improvised explosive device (IED), bomb, or rocket attacks. This shockwave injury is caused when the brain is literally shaken in the soldier’s skull, damaging brain tissue. Warfare and medical technology have increased survival rates, however, by making it possible to treat and mobilize wounded soldiers more quickly and closer to combat zones. TBI has been referred to as the signature injury of the Iraq war, much like Agent Orange poisoning was for the Vietnam War. Doctors at the U.S. Army’s Walter Reed hospital screened all incoming patients between January 2003 and January 2005 and discovered that 60% of all wounded soldiers had some form of TBI (Zoroya 2005). TBI symptoms include severe headaches, impaired memory, and sensitivity to light and sound. These symptoms may be temporary or permanent.

Environmental Impact

One of the most serious, yet overlooked, by-products of war is the mass destruction of ecosystems, also referred to as ecocide (Adley and Grant 2003).

During the Vietnam War, the United States used chemical and biological agents, such as the herbicide Agent Orange, to destroy food crops and defoliate forestlands. Herbicides were used from 1962 to 1969, covering 43% of South Vietnam’s arable land and 44% of its forestland at least once, and in many cases two or more times (Falk 1973). The application rate was 13 times the dose recommended for domestic use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. More than 1.3 million individuals were poisoned or contaminated. The military justified this environmental destruction in order to deny the Vietnamese army protective cover and to cut off the food supply to peasants and soldiers. The contamination of soil and food crops due to Agent Orange continues to threaten the health of the Vietnamese (Adley and Grant 2003). Another method of clearing vegetation and forests in Vietnam was the use of the Rome plow. The plow is a heavily armored Caterpillar bulldozer used to clear several hundred yards on each side of the main roads. It was estimated that about 2,000 acres (3 square miles) were cleared per day until the end of the war. The croplands and forests of Vietnam were damaged, along with rare tree and animal species (Falk 1973).

Other examples of environmental degradation and destruction resulting from war include the burning of oil wells in Kuwait (1991), the health risks associated with the use of depleted uranium weapons in Iraq (since the first Gulf War in 1991), and the destruction of the mountain gorilla habitat in Rwanda (1994) (Adley and Grant 2003).

Waging a war is also a dirty business, as military activities produce harmful waste and debris. Fuel deposits, ammunition dumps, paint, tires, grease, unexploded munitions, and gunpowder contribute to the contamination of land and water (Jorgenson, Clark, and Givens 2012). Military campaigns also consume large amounts of fossil (and nuclear) fuel in planes, ships, and tanks. It is estimated that the U.S. military uses 1.3 billion gallons of oil annually in Middle East alone (Klare 2007).

Efforts to prevent and redress wartime environmental degradation and destruction have not been successful. The primary issue has been accountability—how should a nation be punished for ecocide? The environmental destructiveness of war and conflict has been acknowledged by world leaders, and in 1992 the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (signed by all member states of the United Nations) required states to “respect international law providing protection for the environment in times of armed conflict and cooperate in its further development, as necessary” (United Nations 1992).

Political Impact

Terrorism can effect change in two political areas: the overall distribution of political power and government policies (Crenshaw 1983). Terrorism may result in radical changes in the power relationships within a state, involving shifts in who governs and under what rules. As a target of terrorism, the U.S. government has also experienced a redistribution of power as federal and state agencies have sought to improve intelligence gathering and security procedures. Institutional changes have occurred, with each major intelligence agency improving its antiterrorism activities, culminating in the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. In extreme cases, terrorism may lead to the replacement of one government by another.

Government policies usually have two goals: to destroy the terrorist group and to protect potential targets from attack. Policies may include foreign policy efforts seeking the cooperation and support of international allies. After September 11, the U.S. government attempted to destroy terrorist groups and to ensure U.S. security through a series of executive orders, regulations, and laws. The U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee released a blistering report on the Central Intelligence Agency’s post-9/11 interrogation program. The 2014 report revealed how in a system of covert prisons, CIA officials authorized the use of coercive interrogation tactics—sleep deprivation, humiliation, waterboarding, sensory deprivation, and extreme cold—to obtain information from detainees who were suspected terrorists. The release of the report led to a mixture of condemnation and support from world leaders.

In 2001, Congress passed the Patriot Act, which established a separate counterterrorism fund, expanded government authority to gather and share evidence with wire and electronic communications, allowed agencies to detain suspected foreign terrorists, and provided for victims of terrorism. Constitutional and civil rights attorneys have been critical of the Patriot Act, alarmed that it would erode individual liberties and increase law enforcement abuses. Often cited is the act’s disregard for the principles of political freedom, due process, and the protections of privacy—all principles at the core of a democratic society (Cole and Dempsey 2002). More than 330 cities, towns, and counties, as well as four states, have passed resolutions critical of the federal antiterrorism law (Egan 2004). Two provisions of the act have caused particular concern among citizens. One is the provision that empowers authorities to search people’s homes without notification. A second clause allows government officials the right to review a person’s library, business, and medical records.

The Next Threat

Domestic Terrorism

Michael Leiter, then-director of the National Counterterrorism Center, told the 2011 U.S. House Intelligence Committee that his number-one priority was identifying men and women intent on doing harm in the United States. This included concern with al-Qaeda’s efforts to recruit Americans for their own efforts (Mulrine 2011).

On April 19, 1995, the worst domestic terrorism attack occurred around 9:00 a.m. in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. A rental truck loaded with a mixture of fertilizer and fuel oil exploded in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. The blast blew off the front side of the nine-story building, killing 169 and injuring hundreds more. The attack was conducted by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, motivated by antigovernment sentiment over the failed 1993 federal raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Texas. The bombing occurred on the second anniversary of the Branch Davidian incident. McVeigh was executed for his crime in 2001; Nichols is serving a life sentence.

Louis J. Freeh (2001), former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), identified three types of domestic groups operating in the United States: right-wing extremists, left-wing and Puerto Rican extremists, and special interest extremists. Right-wing groups, such as the World Church of the Creator, Aryan Nations, and the Southeastern States Alliance, advocate the principles of racial supremacy and tend to embrace antigovernment or antiregulatory beliefs. They have also been characterized as hate groups. The Southern Poverty Law Center (2014) identified 939 active hate groups in the United States in 2013.

Left-wing groups want to bring about revolutionary change, adopting a socialist doctrine, and see themselves as protectors of the people. Groups in this category include terrorist or separatist groups seeking Puerto Rico’s independence from the United States and anarchists and extremist socialist groups such as the Workers World Party, Reclaim the Streets, and Carnival Against Capitalism. Many of these anarchist groups were blamed for the damage caused at the 1999 World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle, Washington.

Special interest groups want to resolve specific issues, rather than effect political change. These groups are at the fringes of animal rights, pro-life, environmental, antinuclear, and other political and social movements. Animal rights and environmental groups, such as the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), have recently increased their activities. Activists from these groups usually use arson and incendiary devices equipped with timers to target government and company facilities. The FBI says that these groups are responsible for more than 1,800 criminal acts and more than $110 million in damages (FBI 2009).

In 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that he would reconvene the task force on domestic terrorism. In his announcements, Holder referred to the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing and the 2009 and 2014 shootings at Fort Hood as examples of “the danger we face from these homegrown threats.”

New Terrorist Recruits

Taking a World View

Ireland and the Decommissioning of the IRA

The trouble with the Irish is the English.

—A line from a popular Irish song (quoted in Whittaker 2002)

In August 2007, the British Army ended Operation Banner, a 38-year security operation in Northern Ireland. Violence and bloodshed first began in 1969, the result of confrontations between Nationalist and Unionist (or Loyalist) forces. The Nationalist or Catholic groups were led by the IRA and its splinter groups. In 1970, the Provisional IRA was created (provisional to honor the provisional government declared by the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin). The Provisional IRA formed to defend the Catholic community and to throw out the British army and police (Wilkinson 1993). The Unionist or Protestant forces represented the Ulster Defence Association and its splinter groups: the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Red Hand Commandos, and the Ulster Freedom Fighters. Ulster Protestants saw themselves as Britons, loyal to the Protestant crown. These groups represent “Orange Extremism,” as described by Paul Wilkinson (1993). Orange extremism has also been blamed for provoking the open conflict in the late 1960s and for creating the conditions in which the Provisional IRA could grow. The division between the groups emphasized their polarization in religion, politics, and economics (Whittaker 2002).

Between them, both sides amassed an impressive armory of rifles, homemade machine guns, grenade throwers, antitank weapons, and explosives. Bombing seemed to be a favorite tactic of both sides. In more than 30 years of conflict, 3,500 civilians have been killed and some 30,000 have been injured, and there has been a loss of property amounting to millions of pounds (Whittaker 2002). IRA terrorists also have taken their own lives without attempting to harm others. There was a chain suicide of 11 IRA members who starved themselves to death in a Belfast prison in 1981. The IRA used the hunger strikes and deaths to its organizational advantage, “to reap emotive propaganda, to restore the flow of cash and weapons from the previously dwindling U.S. sources, and to regroup and rearm” (Wilkinson 1993). Many Irish Americans embraced members of the IRA as freedom fighters and supported their cause politically and financially.

In 1998, both sides accepted the Good Friday Agreement, a 65-page document that sought to define relationships within Northern Ireland, between Northern Ireland and the Republic, and between Ireland, England, Scotland, and Wales. The agreement acknowledges that the people of Northern and Southern Ireland are the only ones with the power to bring about a united Ireland. Through the agreement, new government institutions were set in place. A cabinet-style Executive of Ministers, with members in proportion to party support, allows the participation of all groups (Ahern 2003). The new government, composed of unionists and nationalists, was established with the first elections for the new Northern Ireland Assembly in June 1998.

A number of political obstacles slowed down the implementation of the agreement, including difficulties over the total disarmament of the Provisional IRA and the dismantling of British military installations in Nationalist areas (Ahern 2003). After experiencing sectarian squabbling, the assembly failed to hold a session for five years (2001–2006); however, elections were held in March 2007 to reestablish the Northern Ireland Assembly and determine how many members from unionist (Protestant) and nationalist (Catholic) parties would be represented (Lyall and Quinn 2007). Self-rule was restored in Belfast in May 2007.

In 2012, Queen Elizabeth was photographed shaking hands with Martin McGuinness, a former IRA commander, a historic moment in Anglo–Irish relations. McGuinness serves as deputy first minister in Northern Ireland’s provincial government.

Nuclear Weapons

The nuclear weapons age began on July 16, 1945, when the United States exploded the first nuclear bomb in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Three weeks later, an atomic bomb was used on the city of Hiroshima, Japan, killing 100,000 residents. Three days later, an atomic bomb was used on the city of Nagasaki, Japan, killing about 74,000 and injuring 75,000. During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States was engaged in a “cold war” with Russia and other nuclear countries, locked in a stalemate over who would be the first to launch a nuclear attack. In 1963, the countries agreed to sign a partial test ban treaty, banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, under water, and in space, and a nonproliferation treaty was signed in 1968, prohibiting nonnuclear countries from possessing or developing nuclear weapons. In 1996, President Bill Clinton was the first world leader to sign the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which prohibits all nuclear test explosions in all environments. However, the treaty has yet to be ratified by the U.S. Senate. All North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members, except for the United States, have ratified the treaty.

Days after the 1945 bombing of Nagasaki, Japan, the Japanese surrendered to the Allied forces, officially ending World War II. The atom bomb killed more than 70,000 residents and destroyed 70% of the city’s industrial core.

Hiromichi Matsuda

Nuclear weapons are still held by more than eight nations in the world. Suspected weapons have been identified in China (250), France (300), India (80–100), North Korea (<10), Pakistan (90–100), Russia (8,484) the United Kingdom (225), and the United States (7,506) (Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation 2014). In 2010, Iran’s president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad announced that his country was a “nuclear state.” Though his claims could not be independently verified, nuclear watchdog groups and experts say it would take several years for Iran to produce a nuclear weapon. The United States has called for United Nations–backed sanctions to discourage Iran from pursuing its weapons development program.

In 2010, Obama and Russian president Dmitry Medvedev signed a treaty to reduce American and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals by 30%, to the lowest levels since the early years of the Cold War. The United States and Russia possess 95% of the world’s nuclear weapons. The treaty is subject to ratification by lawmakers in both countries and according to Obama and Medvedev sets the stage for further nuclear weapons reduction. Obama has pledged not to develop any new nuclear weapons.

Community, Policy, and Social Action

The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, also known as the 9-11 Commission, was an independent bipartisan commission created by congressional legislation. The 9-11 Commission was charged with documenting and preparing a full account of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Throughout 2003 and 2004, hearings were held investigating Osama bin Laden’s network, the performance of the intelligence community, emergency preparedness and response, and national policy coordination. The commission concluded that U.S. intelligence gathering by the FBI and CIA was inadequate, fragmented, and poorly coordinated.

In 2002, Bush established the Department of Homeland Security. (Before September 11, the U.S. Commission on National Security in the 21st Century [2001] had recommended the creation of a National Homeland Security Agency, responsible for planning, coordinating, and integrating all U.S. agencies responsible for security.) The primary mission of the department is to prevent terrorist attacks and reduce the vulnerability of the United States to terrorism through coordination with component agencies: U.S. Secret Service, U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the Transportation Security Administration. The Department of Homeland Security is also responsible for the Homeland Security Advisory System, which informs the public of the current level of terrorist threat.

As a nation, the United States has used several approaches to combat and to reduce the risk of war and conflict: diplomacy, economic sanctions, and military force. Usually, war is justified as being the last resort in circumstances where there are severe domestic rights violations or international aggression by an offending state (Garfield 2002).

Political Diplomacy

According to Christopher Harmon (2000), “political will, more than new laws or new direction[s] in international politics, is the most important component of an enhanced effort against foreign supported terrorism” (p. 236). Political diplomacy includes articulating policy to foreign leaders, persuading them, and reaching agreements with them (Pillar 2001). Wars reshape diplomacy; victory becomes the goal of foreign policy, and diplomatic relationships are adjusted to achieve it (Mandelbaum 2003). Political scientist Stephen Van Evera (2006) argues that the United States must develop and use its power to make peace.

Relationship building and persuasion are at the heart of U.S. diplomatic efforts. As the lead foreign affairs agency, the Department of State attempts to formulate, represent, and implement the president’s foreign policy (U.S. Department of State 2003). The secretary of state is the president’s principal adviser on foreign policy and represents the United States abroad in foreign affairs. Primarily, the department manages diplomatic relations with other countries and international institutions (such as the United Nations, NATO, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund [IMF]). The Department of State conducts negotiations and concludes agreements and treaties with other countries on issues ranging from trade to nuclear weapons. The United States maintains diplomatic relations with more than 180 countries (U.S. Department of State 2003). Diplomacy is conducted by the secretary of state and by foreign service officers, immigration officers, FBI special agents, intelligence officers, transportation specialists, defense attachés, and other officials (Pillar 2001).

In contrast with the hard-line diplomacy embraced by George W. Bush’s administration, President Obama’s diplomacy has been described as a soft-power approach, where a nation-state is perceived as having values, motives, and actions that should be emulated (Nye 2008). A nation-state with soft power leads with noncoercive persuasion through its attitudes toward international norms, embracing the rules of law and demonstrating respect for diversity and cultural history (Hayden 2011). Political scientist Joseph Nye (2008) describes soft power as: “If I can get you to do what I want, then I do not have to force you to do what you do not want” (p. 95). The president serves as the chief diplomat, setting the tone and agenda for political diplomacy. Obama’s 2009 speech at the Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, has been described as a significant diplomatic address, as the president openly acknowledged the plight of the Palestinians and Israel’s relationship with the United States. Public diplomacy scholar Craig Hayden (2011) writes,

The speech was a signal that the United States would take a more balanced approach to acknowledge the particular perspectives of the Middle East crises. The speech was also important as a function of public diplomacy in the manner of its delivery, its location and the way it signaled the course of U.S. foreign policy in the region. (p. 791)

Obama’s soft-power approach has been praised for improving the U.S.’s status as the world’s most admired country, yet has been criticized for not being effective or strong enough.

The Use of Economic Sanctions

For many years, the United States and the United Nations have used nonviolent approaches in the form of economic sanctions to punish or pressure countries that have violated U.S. laws or values. Sanctions are considered an alternative to diplomacy or military force. Economic sanctions, in the form of trade embargoes and the termination of development assistance, are the most commonly applied form of sanctions, and they have the most significant public health consequences. These sanctions are intended to weaken a rival’s economy, to disrupt their economic and military capabilities.

U.S. sanctions were used against Iraq in 1990 to force its withdrawal from Kuwait and against Yugoslavia (1991–1996) and Serbia and Montenegro (1992–1996) during the Serbian war (Marks 1999). Recent U.S. sanctions have been imposed against Iraq, Iran and North Korea in an effort to discourage terrorist activity or the accumulation of weapons of mass destruction. According to Richard Haas (1997), “economic sanctions are popular because they offer what appears to be a proportional response to challenges in which the interests at stake are less than vital” (p. 75). Sanctions can also serve as a signal of official displeasure with a country’s behavior or action.

Many attempts have focused on cutting aid to countries sponsoring or supporting terrorism. The problem is that most terrorist states do not receive significant aid from the United States, and based on past experience, sanctions have only made target countries and nations more angry and impassioned against the United States (Flores 1981). Shaheen Ayubi et al. (1982) concluded that economic sanctions in U.S. foreign policy may not be effective in their objectives and have often failed to achieve their political purposes. For example, sanctions applied against Cuba since 1960 failed to destabilize the Castro regime.

Sanctions may not hurt dictators and terrorists, but they may increase suffering and death among civilians (Garfield 2002), and research suggests that economic coercion may worsen public health, economic conditions, educational attainment, and the development of a civil society in the sanctioned country (Peksen 2009). According to Dursun Peksen and A. Cooper Dury (2009), “the majority of economic sanctions, so far, have been a blunt economic instrument that hits the whole target economy without any or very few discriminatory measures to lessen the negative impact on civilians” (p. 408). For example, a report issued in 1993 by the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies maintained that sanctions exacerbated malnutrition in Haiti and increased child deaths caused by misgovernment (Neier 1993).

One approach has been to freeze only economic assets while continuing to provide food and medical aid through private agencies (Neier 1993). However, although only economic sanctions were directed against Iraq in the early 1990s, the Harvard Study Team (1991) reported that essential goods—food, medicine, and infrastructure support—were not reaching those in need. All health facilities surveyed reported major drug shortages. Children were most vulnerable, dying of preventable diseases and starvation. The chance of dying before age 5 in Iraq more than doubled, from 54 per 1,000 between 1984 and 1989 to 131 per 1,000 between 1995 and 1999 (Ali and Shah 2000).

Voices in the Community

Aung San Suu Kyi

Between 1989 and 2010, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was a political prisoner in Myanmar (also known as Burma). For more than 15 years during this period, she was detained under house arrest as the Burma junta declared martial law. As reported by Amnesty International (2012), many of Myanmar’s citizens live in poverty and suffer from human rights violations. Political and social dissent is controlled by arrests, torture, and imprisonment. The number of political prisoners in Myanmar is estimated at 1,995 (Amnesty International 2012).

Aung San Suu Kyi was a political prisoner for 15 years in her own country of Myanmar. After her release in 2010, she was elected in 2012 to serve as a representative in the Myanmar parliament, as a member of the National League for Democracy.

© EdStock2/iStock

Suu Kyi served as chairperson of the National League for Democracy (NLD), promoting democracy in the military-ruled country. The organization was banned during her arrest. The military authorities consented to her release in 2010. In 2012, Suu Kyi along with 44 other NLD candidates ran for seats in Myanmar’s parliament. Suu Kyi won her seat. Eighty percent of the parliamentary seats are still held by members of the military-backed ruling party.

After the election, Suu Kyi traveled to Oslo, Norway, to collect her Nobel Peace Prize. She had received the honor in 1991 but due to her imprisonment had not been able to receive her award.

During the 2012 ceremony, Suu Kyi (2012) spoke of her goal for a free, secure, and just society in Myanmar. She spoke of the effectiveness of reform in her country:

We can say that reform is effective only if the lives of the people are improved and in this regard, the international community has a vital role to play. Development and humanitarian aid, bi-lateral agreements and investments should be coordinated and calibrated to ensure that these will promote social, political and economic growth that is balanced and sustainable. The potential of our country is enormous. This should be nurtured and developed to create not just a more prosperous but also a more harmonious, democratic society where our people can live in peace, security and freedom.

Military Response

Military action is based on the idea that the most effective way to defeat an enemy is by the destruction of the enemy’s armies, equipment, transport systems, industrial centers, and cities.

Military intervention has also been defined as a form of humanitarian intervention. Canada’s International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (2001) suggested that humanitarian intervention should be defined as a responsibility to protect. According to the commission, there are three aspects of this responsibility: how to prevent humanitarian crises in the first place, under which conditions and in what way to intervene, and how to maintain peace after a military conflict and rebuild the country. There have been approximately 20 instances of humanitarian intervention since the end of the Cold War. In 2011, evoking the responsibility to protect, the United Nations approved NATO military intervention in Libya to protect civilians from being killed by the armed military forces of Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. Gaddafi had threatened to purge Libya of its civilian protestors. The intervention lasted about six months and led to the collapse of Gaddafi’s 42-year-old regime, the leader’s death, and the installation of a transitional government. Humanitarian warfare continues to be deliberated from ethical, political, and legal perspectives (Zajadlo 2005), as its implementation challenges a basic principle of sovereign power. When does another country have the right to intervene in the business of another?

Retaliation has been the most important counterterrorist use of U.S. military force. The United States first used it against Libya in 1986, responding to the April 4 bombing of a nightclub in Berlin where 2 Americans were killed and 71 were wounded. One hundred military aircraft were used to attack military targets in and around Tripoli and Benghazi in Libya (Pillar 2001). After September 11, 2001, U.S. troops were deployed to destroy Taliban operations based in Afghanistan.

According to Pillar (2001), evidence suggests that military retaliation does not serve as an effective deterrent to terrorism. First, terrorists who threaten the United States present few suitable military targets. It is tough to attack an enemy that can’t be located. Many terrorist groups lack any high-value targets, whose destruction would be costly to their organization. Second, a military attack against a terrorist group may serve political and organizational goals of the terrorist leaders. Such attacks may increase recruiting, sympathy, and resources for terrorist groups. And finally, there is no evidence that terrorists will respond peacefully after a retaliatory attack. Terrorists may also respond by fighting back.

Antiwar and Peace Movements

Antiwar movements have been characterized as reactive, occurring only in response to specific wars or the threat of war. Though every 20th-century war conducted by the United States elicited organized protest and opposition (Chatfield 1992), the public’s response to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars was described as apathetic. The lack of public outrage or protest over the wars was attributed to several factors: the social construction of a common enemy (terrorism), the pervasive rhetoric of patriotism and nationalism, and an overall decline in civic and political engagement. The Bush administration’s policy banning media coverage of fallen soldiers’ caskets was blamed for shielding the public from the personal toll of these wars. (The ban was lifted in 2009.)

Peace movements represent organized coalitions that are “fundamentally concerned with the problems of war, militarism, conscription, and mass violence, and the ideals of internationalism, globalism and non-violent relations between people” (Young 1999:228). According to Nigel Young (1999), there are different peace traditions: groups that provide ideas and initiatives for the entire peace movement. For example, the tradition of liberalism and internationalism attempts to prevent war through reformed behavior of states: peace plans, treaties, international law, and arbitration between all groups. Another tradition, anticonscriptionism, links the peace movement with individual civil rights.

Women as Peacemakers

Another peace tradition is feminist antimilitarism. Peace movements within this tradition are united by the ideal of a distinctive role for women on the issue of peace and female unity across national boundaries (Young 1999). Feminist antimilitary groups first began in the early 1900s. In 1914, Jane Addams, founder of Hull House, led a women’s peace parade in New York to protest World War I. Addams, along with Carrie Chapman Catt, the main strategist and leader for the women’s suffrage movement, and other women activists, formed the Women’s Peace Party in 1915. Later that year, the party was renamed the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. The organization exists today, with chapters in Africa, Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. Its current global mission includes building and strengthening relationships and movements for justice, peace, and radical democracy.

Women have mobilized for peace in other parts of the world: Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Argentina) protested against the political killings and kidnapping of children during the Argentine Dirty War; the Greenham Common Women (England) called for the decommissioning of nuclear arms; and Women in Black (worldwide) are committed to peace with justice, highlighting women’s different experience of war.

College Activists

There is a tradition of student involvement in politics in the United States (Altbach and Peterson 1971). Paul Knott (1971) explains that college students before World War II were mainly upper-middle-class students who treated their education as a privilege. Except for a few campuses, most undergraduates showed little social consciousness and were unwilling to challenge or question the status quo. But increasing diversity on college campuses—in students’ ages, gender, and ethnic backgrounds—helped increase social awareness and infused students with a greater sense of empowerment. Student activism was at its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, supporting the civil rights movement and later protesting the Vietnam War. During the late 1970s, campuses institutionalized many of the gains made in the previous decade: establishing women’s centers, Black student unions, and gay and lesbian organizations and ensuring that student government had a greater role in university operations (Vellela 1988).

Though college students have often been a central force of peace movements, the college student population is less politicized as a whole than it was 45 years ago. According to the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) annual survey of freshmen, 60% of students viewed “keeping up with politics” as “very important” or “essential” in 1966 compared with only 32.8% in 2011 (Pryor et al. 2011). Some argue, however, that progressive student activism didn’t stop after the Vietnam War era (Vellela 1988). Student activism is on the rise, but it doesn’t reproduce the civil rights and war protests of the 1960s and 1970s. Students are engaged in a broad range of issues: women’s rights, discrimination, homophobia, immigration, the homeless, labor unions, and political action groups.

The new wave of peace activism builds on existing networks established by the student anticorporate movement, which focused on economic justice related to sweatshop labor and unionization on campuses (refer to Chapter 9, “Work and the Economy”). The current wave of peace activism includes a diverse set of schools: rural southern schools (Appalachian State University in North Carolina, University of Southern Mississippi), historically Black colleges (Morehouse College, University of Georgia), community colleges from Hawaii to Massachusetts, and urban public universities (City University of New York and University of Illinois–Chicago), as well as high schools and middle schools. Student groups have held teach-ins, vigils, and fasts to call attention to a variety of issues (Featherstone 2003).

Although most recent peace activism has protested against the war in Iraq, this sentiment has not been universal. Student peace groups have been sensitive to the message that they send (Featherstone 2003). Peace groups are linking their opposition to war to the campaign for social justice, dealing with racism, economic inequality, and sexism at home. Student protestors seem to have learned from the protests of the 1960s, wanting to prevent the kind of alienation experienced by Vietnam War veterans.

Sociology at Work

Working and Volunteering Abroad

Michael Clark—Class of 2013

Undergraduate Majors: Sociology, Piano Performance

Pollster John Zogby describes millennials as the “first global generation,” with 60% owning a passport and many expecting to work abroad at some point in their careers (Steiner 2014). There are a host of job and internship opportunities abroad for a recent graduate: teaching, cultural and au pair positions, volunteer work, student internships, short-term contract work, and government or corporate placements (Lacey 2006). An estimated 6.8 million Americans live abroad (excluding those in military service), the highest numbers residing in North, Central and South America and in Europe (U.S. Department of State 2014).

During 2014–2015, Sociology alum Michael Clark traveled and worked through Europe as a volunteer for World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF). Michael is quick to say that his undergraduate study abroad experiences inspired his year abroad. According to the Institute for International Education of Students, students were more likely to enter an international career if they completed an internship abroad and studied in a non-English-speaking country (Lacey 2006).

When asked how he applies sociology to his WWOOF work, Michael replied,

I am drawn particularly to those sociological projects which examine consumption, globalization, and stratification. As a WWOOF volunteer, I apply such a framework to interpret the stories and experiences of these small, organic farmers, such that I may contextualize them within the larger, globalized system of food production. Like George Ritzer, I regard a variety of structural forces—westernization, neoliberalism, and, perhaps most broadly, rationalization—as accounting for a global squandering of both intra and inter-culture diversity. The farmers who work with WWOOF, then, represent an encouraging source of opposition to these very forces. It is understandable, then, that my sociological training compels me to learn more about the slow-food movement, and other related campaigns.

Michael describes several career strategies that helped him narrow his own future prospects:

I find it useful to learn as much as I can about those career trajectories which are interesting and available to me. Consequently, I have spent a great deal of time reading journal articles, books, and essays, from across a diverse body of disciplines. I have also spent a considerable amount of time reflecting on how my own skills and passions might address global social problems, such as stratification, environmental degradation, and the rationalization/westernization of indigenous cultures.

Michael Clark

Courtesy of Michael Clark

After his year as a WWOOFer, Michael will return to the states and hopes to enroll in a PhD Sociology program.

Chapter Review

- 16.1 Explain the difference between war and terrorism

War is a violent but legitimate political instrument between armed combatants. Terrorism is the unlawful use of force to intimidate or coerce compliance with a particular set of beliefs and can be either domestic (based in the United States) or foreign (supported by foreign groups threatening the security of U.S. nationals or U.S. national security).

- 16.2 Explain how the different sociological perspectives examine social problems related to war and terrorism

Functionalists examine how war and terrorism help maintain the social order, creating and reinforcing boundaries. Modern conflict theorists have focused on how war is used to promote economic and political interests, such as replacing social program funding with military expenditures. From the feminist perspective, war is considered a primarily male activity that enhances the position of males in society. Feminist theorists focus on the gender rhetoric used in war. Interactionists focus on the social messages and meaning of war and conflict.

- 16.3 Define the politics of fear

The politics of fear is how decision makers and politicians promote and use the public’s beliefs and assumptions about terrorism to achieve certain goals. The politics of fear changes our behavior and our perspective.

- 16.4 Identify the effects of war and terrorism

A common aftereffect of war is the experience of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The needs of Iraq war veterans are different from veterans of other wars. The United States is the world’s largest military spender. Ecocide is the mass destruction of ecosystems due to war. Examples include the use of Agent Orange to defoliate South Vietnam’s forests during the Vietnam War.

- 16.5 Assess the effectiveness of economic sanctions

Economic sanctions such as trade embargoes, which are the most commonly applied form, may affect the civilian population more than specific leaders or terrorists. Many counterterrorism attempts have focused on cutting off aid to countries sponsoring or supporting terrorism. However, most such states do not receive significant aid from the United States, and sanctions may only worsen living conditions in the targeted country.

Key Terms

- domestic terrorism, 462

- ecocide, 472

- genocide, 458

- humanitarian intervention, 481

- international terrorism, 462

- military-industrial complex, 464

- outcome goals, 462

- politicide, 458

- politics of fear, 467

- process goals, 462

- revolution, 459

- soft-power approach, 479

- terrorism, 460

Study Questions

- From a functionalist’s perspective, how do war and terrorism serve a “safety valve” function?

- How does the military-industrial complex contribute to war and conflict?

- From an interactionist perspective, how has the war on terrorism been socially constructed?

- Identify the psychological, economic, and political impacts of war and conflict.

- Explain warfare as a humanitarian intervention.

- What role have college students and activists played in antiwar and peace movements?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.