Chapter 15 The Environment

Learning Objectives

- 15.1 Explain the relationship between human activity and environmental problems

- 15.2 Review the different sociological perspectives on environmental problems

- 15.3 Discuss climate change and global warming

- 15.4 Summarize federal and state responses to environmental problems

- 15.5 Compare the first wave and second wave of environmental interest groups

- 15.6 Assess the impact of the environmental movement

Mega. That’s the word used to describe recent environmental disasters that have seriously threatened and damaged our physical and social worlds. A megadisaster is defined as a catastrophe that threatens or overwhelms an area’s capacity to get people to safety, treat casualties, protect infrastructure, and control panic (Choi 2011). On April 2010, British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon drilling platform exploded in the Gulf of Mexico. In addition to killing 11 workers and injuring 17 others, the explosion led to the release of an estimated 4.9 million barrels of oil until July 15, 2010, when the damaged wellhead was finally capped. Officials responded quickly to the disaster, addressing the threats to wildlife and to the fishing and tourism industries along the coasts of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Though active cleanup efforts ended in 2014, U.S. Coast Guard crews remain posted on the Gulf Coast ready to respond to new reports of oil.

In 2011, northeastern Japan was struck by a 9.0 earthquake. This megadisaster has been characterized as a natural catastrophe overlaid by a technical situation (Choi 2011): the earthquake was followed by a tsunami and damage to three nuclear reactors in Fukushima. The tsunami leveled 130,000 houses and damaged 250,000 more. About 270 railway lines, 15 expressways, 69 national highways, and 638 municipal roads were closed. Approximately 20,000 people died, most due to drowning, and thousands of residents were displaced. John Schwartz (2011) writes, “The sobering fact is that megadisasters like the Japanese earthquake can overcome the best efforts of our species to protect against them. No matter how high the levee or how flexible the foundation, disaster experts say, nature bats last” (p. 5).

Environmental Problems Are Human Problems

The field of environmental sociology considers the interactions between our physical and natural environment on the one hand, and our social organization and behavior on the other (Dunlap and Catton 1994). Human beings are an integral part of the ecosystem (Irwin 2001). The state of the environment is also influenced by our cultural values and attitudes toward the environment, our social class, our technology, and our relationship with others (Cable and Cable 1995). When we use a sociological perspective to understand environmental problems, we acknowledge that “human activities are causing the deterioration in the quality of the environment and that environmental deterioration in turn has negative impacts on people” (Dunlap 1997:27).

Humans create environmental problems through intentional efforts to exploit or manage nature. Rivers that are dammed, straightened, or treated as sewers may create unintended downstream environmental problems (Caldwell 1997). The removal of rain forests to harvest wood or to create farmland decreases the number of plants and trees that absorb carbon dioxide, leading to higher amounts of greenhouse gases in the air. But environmental problems don’t exist just because of our actions.

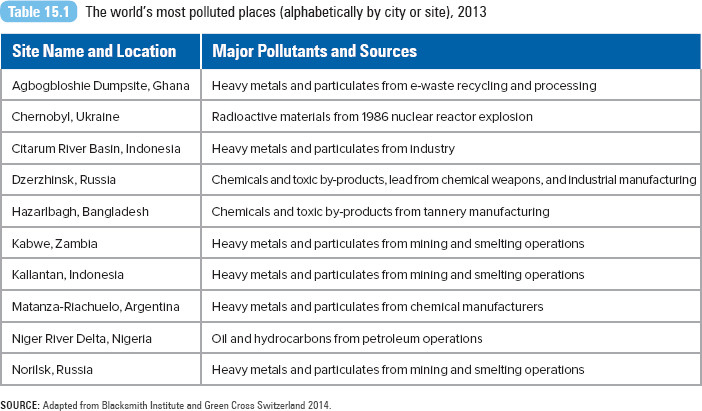

Our pursuit of economic development, growth, and jobs has also led to the degradation of the environment (Caldwell 1997). Russia, Indonesia, and Zambia are among the world’s most polluted places. These countries and their residents (refer to Table 15.1) are exposed to organic and industrial pollutants caused by mining, manufacturing, and transportation. Although much of this pollution can be attributed to the countries’ substandard infrastructures or the absence of regulatory controls, even if both were brought up to industrial country standards, “the legacy of old contamination from the past would continue to poison the local population” (Blacksmith Institute 2007:3).

Environmentalist Paul Hawken (1997) refers to the Biosphere 2 experiment to demonstrate just how vital and fragile our ecosystem is. The Biosphere 2 was a 3-acre, glass-enclosed ecosystem intended to sustain eight people for a two-year experiment, from September 1991 through September 1993. The Biosphere 2’s $200 million budget was not enough to create a viable ecosystem for eight people. By the time the experiment ended, the Biosphere’s air and drinking water were polluted, crops and trees had been killed by other vegetation, and 19 of the 25 small animal species the participants brought with them had died. The scientists who lived in the biosphere showed signs of oxygen starvation from living at the equivalent of an altitude of 17,500 feet. Even with scientific knowledge and planning, there are no human-made substitutions for essential natural resources. As Hawken (1997) explains,

We have not come up with an economical way to manufacture watershed, gene pools, topsoil, wetlands, river systems, pollinators, or fisheries. Technological fixes can’t solve problems with soil fertility or guarantee clean air, biological diversity, pure water, and climatic stability; nor can they increase the capacity of the environment to absorb 25 billion tons of waste created annually by America alone. (p. 41)

Sociological Perspectives on Environmental Problems

Functionalist Perspective

Whether they are looking at a social system or an ecosystem, functionalists examine the entire system and its components. Where are environmental problems likely to arise? Functionalists would answer that problems develop from the system itself. Agricultural and industrial modes of production are destabilizing forces in our ecosystem. Agriculture replaces complex natural systems with simpler artificial ones to sustain select highly productive crops. These crops require constant attention in the form of cultivation, fertilizers, and pesticides, all foreign elements to the natural environment (Ehrlich, Ehrlich, and Holdren 1973). When it first began, industrialization entered a society that had fewer people, less material well-being, and abundant natural resources. But modern industrialization uses “more resources to make few people more productive,” and as a result, “more people are chasing fewer natural resources” (Hawken 1997:40). As much as agriculture, industrialization, and related technologies have improved the quality of our lives, we must deal with the negative consequences of waste, pollution, and the destruction of our natural resources. Human activities have become a dominant influence on the Earth’s climate and ecosystems (Kanter 2007).

A woman stands atop a mountain of rubbish in a China landfill. China generates an estimated 150 million tons of rubbish per year, with as much as 400 million tons estimated by 2020.

© Diego Azubel/epa/Corbis

Biologists Paul Ehrlich and Anne Ehrlich (1990) contend that the impact of any human group on the environment is the product of three different factors. First is the population, second is the average person’s consumption of resources or level of affluence, and third is the amount of damage caused by technology. They present a final formula: Environmental Damage = (People) × (Level of Affluence) × (Technological Damage). A high rate of population growth or consumption can lead to a “hasty application” of new technologies in an attempt to meet new and increasing demands. “The larger the absolute size of the population and its level of consumption, the larger the scale of the technology must be, and, hence, the more serious are the mistakes that are made” (Ehrlich, Ehrlich, and Holdren 1973:15). “What matters to the environment,” writes Robert Engelman (2009), “are sums of human pulls and pushes, the extractions of resources and the injections of waste” (p. 24).

There is no simple way to stop the escalation of environmental problems. Halting population growth would be a good start but by itself could not solve the problem. The United Nations announced in 2011 that the world’s population had reached 7 billion, with 10 billion predicted for 2100 (UN News Centre 2011). Reducing technology’s impact on the environment might be useful, but not if our population and affluence are allowed to grow. According to Ehrlich et al. (1973), the only way to address environmental problems is to simultaneously attack all components.

Let the Environment Guide Our Development

Conflict Perspective

Public discourse on environmental problems is often framed in terms of costs and interests. Do you save the spotted owl habitat or hundreds of logging jobs? Should you close a factory or save the river where its waste is being dumped? The proposed $7 billion Keystone XL pipeline from Alberta, Canada, to the gulf of Texas was the center of our national debate over energy independence, economic growth, and climate change. While supporters refer to the pipeline as a jobs creator and describe it as a means to reduce our dependency on foreign oil, environmentalists warn that transporting raw tar sands oil over 2,000 miles is unsafe and ultimately would prove harmful for people, wildlife, water, and the climate (Natural Resources Defense Council 2014). From this sociological perspective, environmental problems are created by humans competing for power, income, and their own interests.

Our capitalist economic system has been identified as a primary source of the conflict over polluting (or conserving) our natural world. Competing political, economic, and environmental interests ensure that this conflict will continue. J. Clarence Davies (1970) argues that the capitalist system encourages pollution, simply because air and water are treated as infinite and free resources. Polluters don’t really consider who or what is being affected by environmental problems. If a paper mill is polluting the river, it doesn’t affect the paper mill itself but, rather, affects the users of the water or the residents downstream. If a power plant is polluting the air, the plant doesn’t pay for the cost of using the air, but pays only the cost of cleaning up a polluted area (Davies 1970).

Environmental problems occasionally make life unpleasant and inconvenient, but most Americans will tolerate this in exchange for the benefits and comforts associated with a developed industrial economy (Tobin 2000). Environmental damage, pollution, and degradation have become acceptable consequences of doing business. A higher standard of living has been confused with consumption: more is better. As Henri Lefebvre ([1971] 2000) argues, the objective of a consumer capitalist society is to satisfy real or imagined material needs. Television and print media overwhelm us with products and services and tell us that we cannot live without them. Politicians encourage lower taxes so that we have more money to spend. But increased consumption requires increased production and energy, which in turn leads to environmental damage. David Korten (1995) explains,

About 70 percent of this productivity growth has been in . . . economic activity accounted for by the petroleum, petrochemical, and metal industries; chemical intensive agriculture; public utilities; road building; transportation; and mining . . . the industries that are most rapidly drawing down natural capital, generating the bulk of our toxic waste, and consuming a substantial portion of our renewable energy. (pp. 37–38)

Polluters target those with the least amount of power. Race, says Robert Bullard (1999), is the most important factor in determining whether an individual drinks dirty water or lives next to a toxic site. He (Bullard 1994) defines environmental racism as “any environmental policy, practice or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color” (p. 98). Environmental racism is institutionalized through the government, our legal system, and economic forces (Bullard 1999). Research consistently indicates that low-income people and people of color are exposed to greater environmental risks than are those who live in White or affluent communities. Low-income people and people of color suffer higher levels of environmentally generated diseases and death as a result of their elevated risk (Ringquist 2000). Environmental racism has been expanded to include members of other disadvantaged communities, examining heightened environmental risk based on race, class, gender, education, and political power.

Feminist Perspective

The feminist perspective argues that a masculine worldview is responsible for the domination of nature, the domination of women, and the domination of minorities (Scarce 1990), acknowledging that the connection between the environment and women is one of shared oppression (Chircop 2008). Ecofeminism may be the dominant feminist perspective for explaining the relationship between humans and the environment (Littig 2001). Ecofeminism was introduced in 1974 in an effort to bring attention to the power of women to bring about an ecological revolution, using the starting point as women’s experiences. Ecofeminists argue that “men driven by rationalism, domination, competitiveness, individualism, and a need to control, are most often the culprits in the exploitation of animals and the environment” (Scarce 1990:40). According to ecofeminists, “respect for nature generally promotes human welfare, and genuine respect for all human beings tends to protect nature” (Wenz 2001:190). Other feminist approaches include the feminist critique of natural science, feminist analyses of specific environmental issues (work, garbage, consumption), and feminist contributions to sustainable development (Littig 2001).

The Love Canal disaster has been credited with changing public policy regarding toxic waste clean up. New legislation emerged holding polluters responsible for their actions. In addition, Love Canal marks the beginning of the environmental justice movement in the United States, inspiring other citizen groups to advocate for safe and healthy neighborhoods.

Environmental Protection Agency

Cynthia Hamilton (1994) argues that environmental conflicts mirror social injustice struggles in other areas—for women, for people of color, for the poor. In environmental movements, Hamilton explains, what motivates activist women is the need to protect home and children. As the home is defined as the woman’s domain, her position places her closest to the dangers of hazardous waste, providing her with an opportunity to monitor illnesses and possible environmental causes within her family and among her neighbors. As Hamilton sees it, these women are responding not to “‘nature’ in the abstract but to their homes and the health of their children” (p. 210).

The modern environmental justice movement emerged out of citizen protests at Love Canal, near Niagara Falls, New York (Newman 2001). The movement is based on the principle that “all peoples and communities are entitled to equal protection of environmental and public health laws and regulations” (Bullard 1994). For many years, the movement has effectively brought racial and economic discrimination in waste disposal, polluting industries, access to services, and the impacts of transportation and city planning to the public’s attention (Morland and Wing 2007).

At the center of Love Canal’s citizens’ protest movement was a group of local women who called themselves “housewives turned activists.” Lois Gibbs and Debbie Cerillo formed the Love Canal Homeowners Association in 1978. Concerned about the number of miscarriages, birth defects, illnesses, and rare forms of cancer among their families and neighbors, the women worked with Beverly Paigen, a research scientist, to document the health problems in their community (Breton 1998). The information they collected became known as “housewife data” (Newman 2001). The women held demonstrations, wrote press releases, distributed petitions, and provided testimony before state and federal officials (Newman 2001). In 1978, Love Canal was declared a disaster area, some 800 residents were evacuated and relocated, and the site was cleaned up. Gibbs went on to form the Center for Health, Environment and Justice and continues to work on behalf of communities fighting toxic waste problems. More information about Love Canal is presented in the section titled “Hazardous Waste Sites and Brownfields.”

The Love Canal Disaster

Interactionist Perspective

Theorists working within the interactionist perspective address how environmental problems are created and defined. Riley Dunlap and William Catton (1994) explain, “Environmental sociologists have a long tradition of highlighting the development of societal recognition and definition of environmental conditions as ‘problems’” (p. 20). Environmental problems do not materialize by themselves (Irwin 2001). As John Hannigan (1995:55) describes, the successful construction of an environmental problem requires six factors: the scientific authority for and validation of claims; the existence of “popularizers” (activists, scientists) who can frame and package the “problem” to journalists, political leaders, and other opinion makers; media attention that frames the problem as novel and important (such as the problems of rain forest destruction or ozone depletion); the dramatization of the problem in symbolic or visual terms; visible economic incentives for taking positive action; and the emergence of an institutional sponsor who can ensure legitimacy and continuity of the problem.

Social constructionists do not deny that real environmental problems exist. Rather, their interest is in “the process through which environmental claims-makers influence those who hold the reins of power to recognize definitions of environmental problems, to implement them and to accept responsibility for their solution” (Hannigan 1995:185). This perspective helps us understand how environmental concerns vary over time and how some problems are given higher priority than others.

According to Darryn Anne DiFrancesco and Nathan Young (2010), visual communication plays a critical role in many environmental issues, helping to advance or promote a problem to the public. But “global climate change, despite its status as one of the most talked-about and pivotal environmental challenges of our time, appears to lack key visual symbols or metaphors” (p. 531). The authors examined newspaper images of climate change published over a six-month period in Canada’s two national newspapers, The Globe and The National Post, in 2008 and discovered that Canada’s climate change story is told primarily using benign human imagery, focusing on politicians (for example, Canada’s environment minister, John Baird) rather than on scientists or ordinary citizens. Emotive images, such as a polar bear mother with her cub, were rare in their sample. They conclude that the national print media in Canada were not interested in playing up the emotional aspects of the climate change debate. “In our view, the dearth of the clear imagery around global climate change makes it more difficult for ordinary citizens to visualize potential impacts and consequences, and to link (often) abstract language claims to real world and to everyday life” (p. 531).

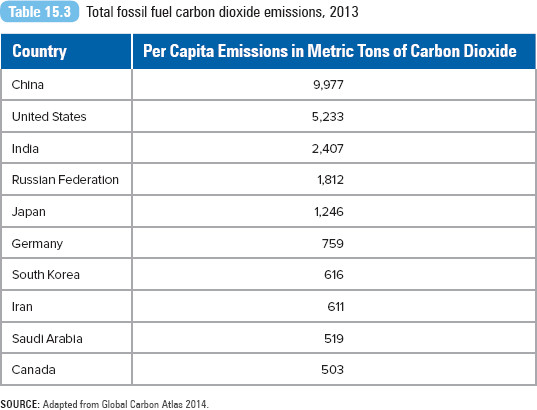

For a summary of sociological perspectives on the environment, see Table 15.2.

Calculate Your Ecological Footprint

Social Problems and the Environment

Climate Change

Climate change refers to any significant change in the measures of climate (temperature, precipitation, or wind patterns) lasting for an extended period of time. Global warming, the ongoing rise in the global average temperature near the Earth’s surface, contributes to climate change. There are also natural causes of climate change, such as ocean changes, volcanic eruption, or changes in the Earth’s orbit.

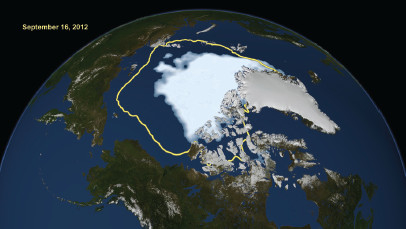

This 2012 NASA image shows the extent of record low Artic sea ice melt. The yellow line marks the sea ice boundaries from the early 1980s. The loss of sea ice affects our global climate and the movement of ocean waters. Too much or too little sea ice also has consequences for wildlife and people who reside in the Arctic.

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio The Blue Marble data is courtesy of Reto Stockli (NASA/GSFC).

To sustain life on Earth, a certain amount of surface heat is required. Heat becomes trapped through the buildup of greenhouse gases—water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other gases—making the Earth’s average temperature a comfortable and sustainable 60 degrees Fahrenheit (Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] 2003b). Over the past century, the Earth’s surface temperature has risen by about 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit (EPA 2012). The problem is the accumulation of specific greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—primarily attributable to human activity during the past 50 years (EPA 2012).

The decade 2000–2009 was the warmest on record for the globe. The global combined land and ocean surface temperature was 0.96 degrees Fahrenheit above the 20th-century average (56.9 degrees Fahrenheit, for the period 1901–2000). In comparison, for the 1990s decade, the combined land and ocean surface temperature was 0.65 degrees Fahrenheit above the 20th-century average (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2010). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that climate change should increase by 2.2 to 11.5 degrees Fahrenheit over the next 100 years (EPA 2012). According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2014 was the hottest year on record worldwide. Michel Jarraud, the organization’s secretary-general, reported that “14 of the 15 warmest years on record have all occurred in the 21st century. There is no standstill in global warming” (quoted in Ford 2014).

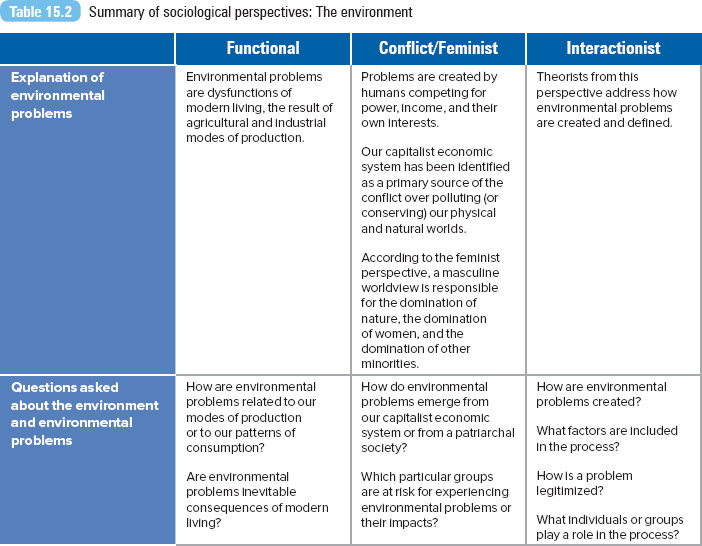

Since the Industrial Revolution, concentrations of carbon dioxide have increased nearly 30%, methane concentrations have increased by 145%, and nitrous oxide concentrations have increased 15% (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1996). Fossil fuels used to run cars and trucks, heat homes and businesses, and power factories are responsible for about 98% of carbon dioxide emissions, 24% of methane emissions, and 18% of nitrous oxide emissions. Agriculture, deforestation, landfills, and mining also add to the amount of emissions. China and the United States have the highest fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions worldwide (a list of the top 10 countries is provided in Table 15.3).

Although they are unable to predict specifically what will happen, where it will happen, and when it will happen, scientists have identified how our health, agriculture, resources, forests, and wildlife are vulnerable to the changes brought about by climate change. Soil moisture may decline in many regions; rainstorms may become more frequent; winters may be colder and longer. Changing regional climates could alter forests, crop yields, and water supplies. Sea levels could rise 2 feet along most of the U.S. coast. In its 2007 report, IPCC (Kanter and Revkin 2007) predicted that the most severe effects would be felt in poor countries and areas facing existing dangers from climate and coastal hazards. Poor households are especially vulnerable to climate change because they lack resources or services to protect themselves and their communities against the threats from changing conditions or crises. Human activity was also identified as the main cause of warming since 1950 (Kanter and Revkin 2007).

During his presidency, George W. Bush downplayed the problem of climate change, referring to the lack of scientific evidence confirming its causes and consequences. In March 2001, President Bush announced that the United States would not support the Kyoto Protocol, which was drawn up in 1997 to implement the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The treaty limits the emissions of greenhouse gases by an average of 5.2% below 1990 levels. According to Bush, the Kyoto regulations would have become too burdensome for U.S. industry at a time when businesses were struggling with a slowing economy. In addition, the president noted that leading world polluters, India and China, were exempted from the treaty.

In his second term, Bush began to reverse his position. In 2005, he agreed for the first time that human action was responsible for climate change, and in 2007, the president called for a long-term plan for cutting greenhouse gas emissions in the United States and throughout the world. Acknowledging how science has “deepened our understanding of climate change,” the president called for other countries to set national targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in 10 and 20 years (Stolberg 2007).

Shortly after taking office, President Barack Obama observed that climate change, if left unchecked, would result in an irreversible catastrophe. While the United States has not yet ratified the Kyoto treaty, during the United Nations Climate Change Conference in 2009, the United States joined an international agreement to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. The nonbinding agreement, dubbed the Copenhagen Accord, brought together industrial and developing nations, such as the United States, China, India, Brazil, and South Africa. The accord calls for limiting the rise in global temperatures to no more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit and for economic support for emerging countries to develop low-carbon energy systems, to adapt to climate change, and to protect tropical forests (Broder 2010). The nations’ leaders acknowledged that climate change is “one of the greatest challenges of our time. . . . We recognize the critical impacts of climate change and the potential impacts of response measures on countries particularly vulnerable to its adverse effects and stress the need to establish a comprehensive adaptation programme including international support” (United Nations 2009). In 2010, the Obama administration announced the formation of a National Climate Service agency to work with the NOAA’s National Weather Service and National Ocean Service. Funding for the new agency was blocked by congressional lawmakers in 2011.

Climate Change: Watching the World Change

Air Quality

The quality of the air we breathe is subject to pollution from two sources: particulate matter and smog. Research has linked air pollution to acute and chronic illnesses (e.g., burning eyes and nose, asthma) as well as death. Air pollution also leads to environmental and property damage.

Particulate or particle pollution is caused by the combustion of fossil fuels—the burning of coal, diesel, gasoline, and wood. Particulate matter includes road dust, diesel soot, ash, wood smoke, and sulfate aerosols that are suspended in the air (Natural Resources Defense Council [NRDC] 1996). The EPA is concerned about small particulate matter, 10 micrometers in diameter or smaller, because these smaller particles are able to pass through the throat and nose and enter the lungs, causing respiratory problems (EPA 2007a).

A man rides his bike past a coal fired powerplant in Fuxin, China. In 2012, Chinese officials selected Fuxin as the site of a national tourist attraction, promising to clean up the city and transform its reliance on coal.

SHENG LI/REUTERS/Newscom

Particulate pollution caused by traffic and diesel engines is a growing problem in many European Union cities. The World Health Organization (WHO) set the acceptable air quality standard at 10 micrograms of particles per cubic meter. However, nowhere in Europe is this standard being met—at the lower end of the spectrum are Paris and London (16 micrograms per cubic meter), and at the highest are cities such as Warsaw (34), Turin (41), and Milan (38) (Rosenthal 2007). The standard in the United States is 15 micrograms per cubic meter.

Smog or ground-level ozone has been referred to as a public health crisis, affecting people in nearly every U.S. state (Clean Air Network 2003). Smog is formed when nitrogen oxides emitted from electric power plants and automobiles react with organic compounds in the presence of sunlight and heat. Our reliance on automobiles has been blamed for much of the increase in smog levels.

The EPA monitors smog levels throughout the nation. The EPA sets federal eight-hour smog standards and collects data on the number of days that exceed the standard. A day is considered unhealthy if smog levels exceed the eight-hour standard. The EPA reported that 2002 was the worst recorded smog season; the eight-hour health standard was exceeded 8,818 times nationwide. The states with the highest number of unhealthy ozone days were California, Texas, and Tennessee (Clean Air Network 2003). In 2008, the EPA revised national air quality standards, the first time standards have been tightened since 1997. Nationally, ground-level ozone concentrations in 2013 were among the lowest since 2002 (EPA 2010, 2014a).

Scientists report that one of every three people in the United States is at a higher risk of experiencing ozone-related health effects. Those most vulnerable to the health effects of smoggy air are children, people who work or exercise regularly outdoors, the elderly, and people with respiratory diseases. Short-term effects of smog mostly attack the lungs and lung functioning, irritating the lungs, reducing lung function, aggravating asthma, and inflaming and damaging the lining of the lungs (EPA 1999).

During the past two decades, the prevalence of asthma has increased globally, suggesting growing problems associated with indoor and outdoor air quality. Among children, who tend to be outdoors more than adults, asthma is the most common chronic disorder worldwide (WHO 2006), the leading cause of missing school, and the leading cause of hospitalization (Eisele 2003). In the same way that the ozone damages human health, it affects the health of other animals and vegetation and damages buildings (C. Palmer 1997).

Hazardous Waste Sites and Brownfields

The story of Love Canal awakened the world to chemical dumping hazards (Breton 1998). During the 1940s and 1950s, the Hooker Electrochemical Company dumped 20,000 tons of chemicals into the Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York (Center for Health, Environment and Justice 2001). In 1953, after filling the canal and covering it with dirt, the company sold the land to the Board of Education for a dollar. Homes and an elementary school were built next to the canal. By the late 1970s, dioxin and benzene chemicals began seeping through backyards and basements. Because of the efforts of the Love Canal Homeowners Association, state and federal agencies responded by cleaning the area and relocating many residents. In 1995, the Occidental Chemical Corporation (which bought out the Hooker Electrochemical Company) agreed to pay the government $129 million to cover the costs of the incident.

As a result of the Love Canal incident, the EPA created the Superfund program to clean hazardous waste sites. Hazardous materials may come from chemical manufacturers, electroplating companies, petroleum refineries, and common businesses such as dry cleaners, auto repair shops, hospitals, and photo processing centers (EPA 2003a). Sites may be placed on the national priority list (NPL) by their state if they meet specific hazard and cleanup criteria. As of December 2014, 1,322 NPL sites had been identified; of these, 385 sites had been removed from the list after cleanup efforts were completed (EPA 2014b).

Toxic sites continue to be identified today. The Childproofing Our Communities Campaign is a collaboration of groups concerned about children’s environmental health. The campaign focuses on where children spend most of their time: in school. In its 2001 report, the campaign identified more than 1,100 public schools within a half-mile radius of known contaminated sites in California, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, and New York. The campaign estimates that more than 600,000 students attend classes in schools near contaminated land (Center for Health, Environment and Justice 2001). In a state-by-state survey of laws and regulations regarding the siting of new school construction, the campaign reported that only 14 states restrict siting schools on or near hazardous or toxic waste sites, five states have cleanup standards for contaminated soil, and eight states have funding available for the cleanup process (Center for Health, Environment and Justice 2009).

In 2002, President Bush signed the Brownfields Revitalization Act, which authorized up to $250 million annually for the cleanup of brownfields. Brownfields are abandoned or underused industrial or commercial properties where expansion or redevelopment is complicated by the presence or potential presence of hazardous substances, pollutants, or contaminants. There are more than 450,000 sites throughout the United States. Redevelopment efforts have included restoring waterfront parks and converting landfills to golf courses, as well as commercial and business expansion (EPA 2003a).

Taking a World View

Home Sweet Landfill

China and the United States produce more waste than any other countries in the world. Traditional waste disposal includes incineration and landfills. Most U.S. waste, about 251 million tons per year, is sent to landfills. Each American creates 4.38 pounds of trash per day (EPA 2014c). Landfills have been identified as one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, primarily methane (an odorless, colorless gas caused by the decomposition of animal and plant matter).

Yet, in many countries, many individuals and families call landfills their homes. In Mexico, landfill residents are called pepenadores. To make money, they scavenge through garbage piles, finding items (appliances, metals, or clothing) that can be reused or sold. Meals are harvested from discarded waste, and they build their homes using scrap material. Matthew Power (2006) explains, “Household and industrial trash has become for the world’s poor a more viable source of sustenance than agriculture and husbandry” (p. 62).

In his article “The Magic Mountain,” Power (2006) focuses on life on Payatas, a 50-acre landfill in Quezon City, the Philippines. Here the scavengers are called mangangalahigs, which translated means “chicken scratchers,” describing the way they pick through piles of trash. Payatas has been called the “second Smoky Mountain.” The first Smoky Mountain was a landfill site in Manila that supported about 30,000 men, women, and children who lived on the landfill. In 1995, the Philippine government closed the site, moving residents to temporary housing. However, over time, some Smoky Mountain residents moved to Payatas and resumed their lives as mangangalahigs.

Those who live on or scavenge from landfills are at high risk for death or disease. Landfills are unsafe environments, producing methane gas, and leachate, a toxic fluid that is produced from compressed trash.

© FannyOldfield/iStock

Power (2006) claims that so much garbage is piled at the Payatas dump that it would take 3,000 trucks a day for 11 years to move it all to another landfill. He writes,

As trucks dump each new load with a shriek of gears and a sickening glorp of wet garbage, the scavengers surge forward, tearing open plastic bags, spearing cans and plastic bottles with choreographed efficiency. . . . The ability to discern value at a glimpse, to sift the useful out of the rejected with as little expenditure of energy as possible, is the great talent of the scavenger. (p. 62)

Scavengers can make as much as 150 pesos a day, about $3 for their work on the dump.

Scientists have collected global evidence identifying the unhealthy consequences of landfills on human health. An increased risk of adverse health effects (e.g., low birth weight, respiratory illnesses, birth defects, and certain types of cancers) has been found near individual landfill sites and in several multisite and multicountry studies (Vrijheid 2000).

A zero-waste movement is growing in the United States. Consumers and businesses are encouraged not to use polystyrene foam containers or any packaging that is not biodegradable. Several cities have initiated yard waste composting collection and expanded their collection of recyclable household items beyond the traditional paper, glass, and aluminum to include tires, batteries, and household appliances (Kaufman 2009).

Water Quality and Supply

A 2003 study conducted by the Pew Oceans Commission revealed a crisis in U.S. waters caused by pollution and fishing practices (Weiss 2003). The commission expressed concern about runoff from agricultural fields, lawns, and roads. Oil from gas stations and nutrients from agricultural fields disrupt the balance of river and ocean ecosystems, leaving very little dissolved oxygen in the waters. A dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico near the mouth of the Mississippi River stretches more than 5,000 miles long. With not enough oxygen for survival, there is little marine life within the zone. There are 200 dead zones in U.S. waters (the Gulf dead zone is the largest) and an estimated 400 to 1,000 dead zones worldwide (B. Palmer 2014).

Toxic substances are turning up with greater frequency in groundwater, the source of drinking water for one of every two Americans (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1996). The EPA (2009a) reports, “While tap water that meets federal and state standards generally is safe to drink, threats to water quality and quantity are increasing.” Our drinking water is monitored in more than 55,000 community water systems for more than 80 known contaminants, including arsenic, nitrates, human and animal fecal waste, and legionella (the cause of Legionnaire’s Disease).

As the conflict perspective warns, economic activity also contributes to environmental damage. Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is the process of extracting natural gas from shale rock layers underground. A combination of water, sand, and chemicals is injected into the shale rock to release the gas. The process is controversial for its environmental impact on our water supply: first for the use of water in the extraction process and second for the chemicals that may contaminate the groundwater supply. The state of Vermont was the first U.S. state to ban fracking.

According to the United Nations, approximately 780 million people do not have access to a decent source of drinking water and 2.5 billion do not have access to proper sanitation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014). Representatives from 100 countries at the World Water Forum recognized water as a basic human need. Other countries and organizations, including the WHO, have recognized water as a basic human right.

Only 1% of the world’s water can be used for drinking. Nearly 97% of the water is salty or undrinkable; the other 2% is in ice caps and glaciers (EPA 2003b). Freshwater comes from surface water sources (lakes, rivers, and streams) and groundwater sources (wells and underground aquifers). About 66% of people get their drinking water from surface water sources. Large metropolitan areas rely on surface water, whereas small communities and rural areas depend on groundwater sources. In recent years, there has been growing concern about the availability of freshwater sources. Because of pollution, increasing urbanization, and sprawling development, we may be running out of freshwater.

Almost 30 million residents in seven western states (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and California) rely on the Colorado River for their drinking water. The river basin covers 240,000 square miles in the United States and a portion of northwestern Mexico. So much of the river is diverted for drinking and agricultural use that by the time it reaches the Sea of Cortez, it isn’t much more than a trickle. A 2007 report by the National Research Council on the Colorado River concluded that the combination of limited water supplies, increasing population demands, warmer temperatures, and the prospect of future droughts is likely to cause conflict among existing and future water users. The report predicted that this would “inevitably lead to increasingly costly, controversial, and unavoidable trade-offs among water managers, policy makers, and their constituents” (National Academies 2007).

Since 2011, the state of California has been gripped by a severe drought, impacting the lives of many Californians through lost agricultural jobs, shrinking lakes and rivers, dead or dying lawns, and in some cases, dry toilets and washing machines. State leaders have had to make tough choices to meet the increasing demands on the state’s limited water supply. The scientific community was split on whether the atmospheric conditions were due to natural variability or related to human-caused climate change. Some scientists attributed the drought to atmospheric conditions. Unusually warm temperatures and persistent ridges of high-pressure air over the northeastern Pacific prevented winter storms from reaching California during its typical 2013 and 2014 rainy seasons. The storms also bypassed Oregon and Washington (Than 2014).

Toxic Water

Exploring social problems

Waste and Recycling

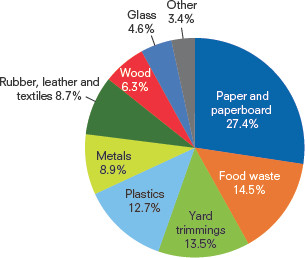

In 2012, Americans generated 251 million tons of trash. Per person per day, this equates to 4.38 pounds of trash or municipal solid waste (MSW). The types of MSW we discarded are presented in Figure 15.1. Identify the top three MSW materials discarded in 2012.

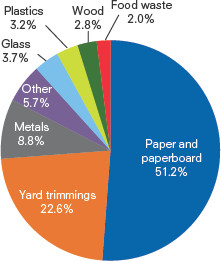

Approximately 65% of the trash ends up in 1,500 landfills and incinerators; the rest of the material is recovered or recycled (refer Figure 15.2). In 2012, Americans recycled and composted 87 million tons of MSW.

Figure 15.1 Total MSW generation before recycling (by material), 2012

SOURCE EPA 2013.

Figure 15.2 Total MSW recovery (by material), 2012

SOURCE EPA 2013.

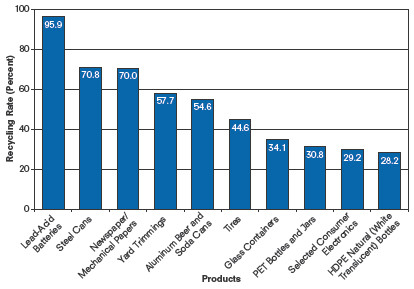

Figure 15.3 Recycling rates of selected products, 2012

SOURCE EPA 2013.

What Do You Think?

The EPA (2013, p.10) explains the value of recycling:

Some waste products are recycled at a higher rate (refer to Figure 15.3).

Recycling has environmental benefits at every stage in the life cycle of a consumer product—from the raw material with which it’s made to its final method of disposal. By utilizing used, unwanted, or obsolete materials as industrial feedstocks or for new materials or products, Americans can each do our part to make recycling, including composting work. Aside from reducing GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions, which contribute to global warming, recycling, including composting also provides significant economic and job creation impacts.

What items do you regularly recycle? How did you learn about recycling?

Land Conservation and Wilderness Protection

Efforts in land conservation and wilderness protection seem to be successful largely because of federal protection policies. Since adopting the 1964 Wilderness Act, Congress has designated more than 106 million acres as “wilderness areas” through the National Wilderness Preservation System (2004). Under the act, timber cutting, mechanized vehicles, mining, and grazing activities are restricted. Human activity is limited to primitive recreation activities. The wilderness lands are protected for their ecological, historical, scientific, and experiential resources. The areas range in size from the smallest, Pelican Island, Florida (5 acres), to the largest, Wrangell–St. Elias, Alaska (almost 10 million acres of land).

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 attempts to preserve species of fish, wildlife, and plants that are of “aesthetic, ecological, educational, historical, recreational and scientific value to the Nation and its people.” The act has been controversial because it preserves the interests of the species above economic and human interests. For example, if endangered species are present, the act will restrict what landowners can do on their land (C. Palmer 1997). Currently, 2,000 U.S. and foreign animal and plant species have been listed as endangered or threatened, with recovery plans approved or implemented for 1,138 species (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2012). Although federal funding for the Endangered Species Act expired in October 1992, Congress has appropriated funds in each fiscal year to support the program.

The National Park System includes 397 national parks covering more than 84 million acres. Unlike the National Wilderness Preservation System, the National Park System allows and supports recreational activities. However, human activity in the form of motorized access, road and highway developments, logging, and pollution threatens the health of several national parks. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most visited national park, with about 10 million visitors each year (National Parks Conservation Association 2003). The park features an ecosystem of rare plants and wildlife along with historical structures representing southern Appalachian culture, all of which are endangered according to the National Parks Conservation Association. The park has been listed as “endangered” for several years, primarily because of chronic air pollution problems. The pollution has been attributed to coal-fired power plants and other industrial sources. Local developers are allowed to build right up to the park’s boundaries.

Community, Policy, and Social Action

Federal Responses

The government’s first response to the environment was directed at cleaning the nation’s polluted water, air, and land. In 1969, Congress adopted the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a comprehensive policy statement on our environment. For the first time in our nation’s history, the government was committed to maintaining and preserving the environment (Caldwell 1970). The EPA, established in 1970, is charged with providing leadership in the nation’s environmental science, research, education, and assessment efforts (EPA 2004). As the chief environmental agency, the EPA sets national standards and delegates to states and tribes the responsibility for issuing permits and monitoring and enforcing compliance. Beginning in the 1980s, the agency shifted its policies from cleanup to pollution management or prevention through market-based and collaborative mechanisms with business and industry and environmental strategic planning (Mazmanian and Kraft 1999). Additional environmental legislation, some of which we have already reviewed, includes the following:

- The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act and the Wilderness Act of 1964. In our discussion on land conservation, we already reviewed the Wilderness Act. The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act provides the necessary funds and assistance to states in planning, acquiring, and developing recreational lands and natural areas. The act also regulates admission and special user fees at national recreational areas. These two acts have been referred to as the “initial building blocks of environmental action” (Caulfield 1989:31).

- The Clean Air Act of 1970 regulates air emissions from area, stationary, and mobile sources. The act helped establish maximum pollutant standards. In 1990, the Clean Air Act was amended to address acid rain, ground-level ozone, ozone depletion, and air toxins. In 2003, seven state attorneys general filed a lawsuit against the EPA, accusing the agency of neglecting to update air pollution standards. The suit seeks regulations on carbon dioxide emissions, which are not listed under the Clean Air Act (Lee 2003). In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court found in favor of the seven states, ruling that greenhouse gases are air pollutants covered by the Clean Air Act (EPA 2009b).

- The Clean Water Act followed in 1972. This act established standards and regulations regarding the discharge of pollutants into the waters of the United States. The EPA was authorized to implement pollution control programs, setting wastewater standards and water-quality standards for all contaminants in surface waters.

- The Endangered Species Act of 1973 created a program for the conservation of threatened and endangered plants and animals and their habitats.

- Under the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976, the EPA has the authority to track 75,000 industrial chemicals being produced or imported into the United States.

- The Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 modified earlier statutes and created a single, health-based standard for all pesticides in foods.

In its strategic plan for 2014–2018, the EPA identified five goals: addressing climate change and improving air quality, protecting America’s water supply, cleaning up communities and supporting sustainable development, ensuring the safety of chemicals and preventing pollution, and protecting human health and the environment through law enforcement and compliance.

State and Local Responses

The EPA highlights work done by states in “developing and implementing a range of programs and strategies that are cost-effectively reducing greenhouse gases, improving air quality, enhancing economic development and increasing the nation’s energy security” (EPA 2007b). Calling state action “a key component of the U.S. response to climate change,” the agency notes that 35 states and Puerto Rico have completed or implemented action plans for reducing greenhouse gas emissions or enhancing greenhouse gas capture.

Recognizing that there are no real borders for carbon emissions and becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow progress of federal legislation on the matter (Broder 2007), many state leaders formed regional coalitions to combat climate change. For example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a cooperative effort by northeastern and mid-Atlantic states to determine a regional strategy for controlling greenhouse gas emissions. In 2006, the Clean and Diversified Energy Initiative was signed by governors of 19 western states, along with those from American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The goal of their initiative is to identify and produce affordable, sustainable, and environmentally responsible energy for the western states and islands.

Cities throughout the nation have embraced sustainability goals, along with environmentally responsible planning and consumption. In 2005, the U.S. Conference of Mayors endorsed the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement. Through the agreement, the mayors agreed to strive to meet or exceed Kyoto Protocol targets for reducing global warming pollution. More than 600 mayors have signed the agreement.

Two major U.S. cities made news for their environmental vision and leadership. Declaring New York City the “first environmentally sustainable twenty-first-century city,” then-mayor Michael R. Bloomberg proposed a master plan to reduce energy consumption in six areas by 2030: land, transportation, water, energy, air quality, and climate change. Much of the plan would require state approval. One of the most contentious strategies involved the city’s transportation burdens. Calling it “congestion pricing,” Bloomberg proposed charging a fee for vehicles entering the city from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays—$8 for cars and $21 for trucks. The pricing plan would have reduced traffic congestion and improved air quality, as it has in parts of London and Singapore (Lueck 2007). Despite approval from the New York City Council, the state legislature failed to pass the pricing plan.

On the West Coast, San Francisco was the first city in the nation to ban the use of petroleum-based shopping bags. These plastic shopping bags take many years to degrade, meanwhile contaminating our land and water and endangering animal and marine life. Nearly 90% of all U.S. shopping bags are plastic. Beginning in 2007, plastic bags were to be replaced with biodegradable plastic bags or recyclable bags in San Francisco grocery and drug stores. Several countries, including Bhutan, Bangladesh, and China, have banned the use of nonbiodegradable plastic bags. Other countries, such as Germany and Ireland, charge a nominal fee for plastic shopping bags.

Handling Smog

Environmental Interest Groups

Organizations concerned with the protection of the environment have played an important role in American politics since the foundation of the Sierra Club in 1892. The first wave of environmental interest groups included the National Audubon Society (1905), the National Parks Conservation Association (1919), and the National Wildlife Federation (1935). These groups were concerned with land conservation and the protection of specific sites and wildlife species. These first-wave groups depended on member support and involvement. These organizations remain among the most influential groups in the environmental movement (Ingram and Mann 1) and saved the University of New Hampshire $10,000 in waste (989).

As public attention shifted to the problems of environmental pollution, a second wave of environmental groups emerged during the 1960s and 1970s. These new organizations focused their efforts on fighting pollution. In general, the second wave of environmental groups adopted an ecological approach to our natural environment, recognizing the interrelationship between all living things and using science as a tool for understanding and protecting the environment. The Environmental Defense Fund (1967) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (1970) were started with funding support from the Ford Foundation. Both organizations relied on litigation as their instrument of reform. Other second-wave groups include Friends of the Earth, the Environmental Policy Institute, and Environmental Action. After the 1970s, environmental groups began to direct their appeals to policy makers rather than to the general public (Ingram and Mann 1989).

Although each group is committed to the environment, each has adopted its own cause, from broad environmental themes to such specific problems as toxic pollution or land conservation. The groups also have different strategies and tactics. Environmental groups may attempt to influence political policy, litigate environmental disputes, form coalitions with other environmental or interest groups, or endorse specific political candidates (Ingram and Mann 1989). Some, such as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, which rams and sinks whaling vessels throughout the world’s oceans, adopt “in-your-face” tactics.

Now more than 75 years old, the National Wildlife Federation has eleven field offices and 47 state affiliates, including Washington, DC, and the Virgin Islands. The affiliates operate at the grassroots level by working to educate, encourage, and facilitate conservation efforts at the state level. One such organization is the Arkansas Wildlife Federation, established in 1936 by a group of sportsmen. The federation’s goal has been to serve as a leader in educating people about conservation issues and in encouraging responsible stewardship of the state’s natural resources. The federation, which represents a variety of constituents—hunters, sportsmen, hikers, anglers, and campers (Arkansas Wildlife Federation 2003a)—sponsors a variety of educational and community activities and projects. Seminars are offered to the public covering issues such as forest management, wetlands and water management, hunting, and fishing. The federation sponsors annual conservation achievement awards to honor citizens and organizations dedicated to natural resource endeavors. The organization also sponsors political candidate forums where citizens can ask candidates about their positions on various conservation and environmental issues (Arkansas Wildlife Federation 2003b).

A new environmental interest group is the Earth Island Institute, founded in 1982 by David Brower, who was the first executive director of the Sierra Club and cofounder of Friends of the Earth. The institute supports more than 100 projects worldwide, pledging to support campaigns “dedicated to conserving, preserving, and restoring the ecosystems on which our civilization depends” (Earth Island Institute 2010). The organization also honors youth for their environmental community work. Among those recognized in 2013 was Alex Freid, a University of New Hampshire student. At the end of his freshman year, Freid was stunned by the amount of good and usable items discarded when students moved out of their dorm rooms and apartments. He was inspired to establish the Post-Landfill Action Network or PLAN, a nonprofit cooperative network that helps college students create zero-waste solutions on their campuses. Within three years, PLAN diverted more than 100 tons of reusable waste from landfills and saved the University of New Hampshire $10,000 in waste disposal costs (Brower Youth Awards 2013).

Green Schools Initiative

Environmental Justice Movement

Sherry and Charles Cable (1995) argue that the grassroots environmental movement has improved the lives of many individuals and has spread environmental awareness among the public. In contrast to national environmental organizations, grassroots organizations usually consist of working-class participants, people of color, and women. Although experienced organizers or community activists lead some groups, many grassroots groups are led by inexperienced but passionate leaders. In the fight against environmental racism, these grassroots environmental groups have given a voice to communities of color (Epstein 1995) and have redefined environmental protection as a basic right (Bullard and Johnson 2000).

Grassroots organizations emphasize environmental justice, acting in the belief that some injustice has been committed by a corporation, business, or industry and that appropriate action should be taken to correct, improve, or remove the injustice(s). Environmental justice is defined as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies” (Bullard and Johnson 2000:558). The movement embraces a holistic approach in creating environmental health policies and regulations: ensuring community-based collaborative partnerships, enhancing public participation in environmental decisions, promoting community empowerment, and ensuring community-based sustainable economic development (Bullard and Johnson 2000).

These organizations have tackled a variety of environmental problems and have sought justice for housing, transportation, air quality, and economic development issues (Bullard 1994). In 2011, responding to the nuclear fallout from the Fukushima nuclear plant, citizen monitoring groups were formed across Japan. Men and women armed with dosimeters began taking radiation readings near their homes. The organized effort grew out of a perceived lack of government response and citizens’ disbelief in the government’s insistence that the nuclear fallout would not pose a threat or contaminate food sources (Tabuchi 2011).

Sociologists Riley Dunlap and Angela Mertig (1992) note that the environmental movement is among the few movements that have “significantly changed society” (p. xi). Nicolas Freudenberg and Carol Steinsapir (1992:33–35) identify seven achievements of grassroots organizations:

- A number of environmentally hazardous facilities have been controlled by cleaning up contaminated sites, blocking the construction of new facilities, and upgrading corporate pollution control equipment.

- Grassroots organizations have forced businesses to consider the environmental consequences of their actions.

- These groups encourage preventative approaches to environmental problems, such as reducing or limiting the use of environmental contamination.

- The grassroots movement has expanded citizens’ right to participate in environmental decision making.

- Grassroots organizations have served as psychological and social support networks for victims and their families.

- The movement has brought environmental concerns and action to working-class and minority Americans.

- The grassroots movement has influenced how the general public thinks about the environment and public health.

In Focus

Local and Sustainable Food

After cars, our food system uses more fossil fuel than any other sector of the economy, about 19% (Pollan 2008). According to the Worldwatch Institute, food in the average American meal travels about 1,500 miles from farm to home. Food is brought into most communities via trucks, trains, or airplanes in refrigerated or storage containers. The 1,500-mile meal is said to consume as much as four times the energy and produce four times as much greenhouse gas emissions as a locally grown meal (Ketcham 2007). In addition to energy expended for transport, concern has been expressed over the amount of fossil fuel energy used in producing the food products brought to our table. In 2009, the Swedish National Food Administration began requiring the reporting of carbon dioxide emissions associated with the production of specific foods. For example, one serving per week of beef from dairy cows produces 120 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions per year. The information will appear on some grocery items and restaurant menus throughout the country (Rosenthal 2009).

Local farmer’s markets, like this one in Seattle, Washington, help support local farmers and encourage seasonal food consumption.

© Candice Cusack/iStock

In response, environmentalists and foodies (people who have an avid interest in the latest food fads) throughout the United States and elsewhere in the world have adopted what is referred to as the 100-Mile Diet. For a week, a month, a year, or life, the rules of the diet are simple: you may only consume food grown and produced within a 100-mile radius of your home. Called locavores, these 100-mile eaters advocate the value in being able to know the source of your food, supporting the local economy, and eating fresh and healthy food in season. They argue, “The distance from which our food comes represents our separation from the knowledge of how and by whom what we consume is produced, processed and transported” (Locavores 2007). This is not a diet for fast-food junkies.

Canadians Alisa Smith and J. B. MacKinnon first coined the term 100-Mile Diet when they began a yearlong local food experiment in Vancouver, British Columbia. The couple discovered several food items that they had to live without for most or part of the year, such as chocolate, coffee, and wheat. (Most locavores make exceptions for these items, including salt and spices.) Unable to purchase local bread and wheat for baking, for one lunch meal, MacKinnon, the family chef, fashioned bread out of turnip slices. But the couple found success (eventually finding a local supplier of wheat) and satisfaction in their diet. Their experience helped fuel broader interest in the benefits of a 100-mile diet.

One way to support local agriculture is through community-supported agriculture (CSA), a partnership between community members and an independent local farm. The CSA movement began in Japan almost 30 years ago with a group of women who were concerned about pesticides, the increase in processed foods, and their country’s shrinking rural population. Community members purchase seasonal shares, for about $300 to $400, which entitles them to weekly food allowances throughout the growing season. According to FoodRoutes.org, independent local farms encourage biodiversity by diversifying the local landscape and natural environment. The CSA arrangement is beneficial to the farmer and to his or her customers. Customers receive fresh produce and have the satisfaction of supporting a local business. Customers can help at the farm and provide input and suggestions to their farmer. Instead of spending time marketing produce, farmers can focus their efforts on growing quality produce and working with their community members.

Alongside first graders from Bancroft Elementary School in Washington, DC, Michelle Obama broke ground on an organic vegetable garden on the South Lawn of the White House. This is the first garden at the White House since Eleanor Roosevelt’s World War II victory garden. The garden was planted with a variety of lettuces, greens, and herbs as well as a patch of berries. At the planting, Mrs. Obama expressed her interest in promoting healthy eating and local food, particularly from the more than 1 million community gardens throughout the country.

Voices in the Community

Chad Pregracke

Chad Pregracke started his career as an environmental activist in his own backyard. A native of Hampton, Illinois, he spent most of his life on the shores of the Mississippi River as a resident, shell diver, and commercial fisherman. Pregracke often saw garbage floating on the river or caught within its banks.

I woke up like that many times—loving the natural world and hating the despicable mess. I saw the garbage on the river, and it didn’t look right. It may have been commonplace, but I didn’t like it and I didn’t accept it. And the more garbage sites I noticed, the more it made me want to do something about it. (Pregracke and Barrow 2007:12–13)

He admits that his attempts to organize and fund his first river cleanup were less than perfect. He recalls how he did everything wrong. He didn’t have a clear message, didn’t have a plan, and didn’t talk to the right people at local agencies. But he persevered and received funding from his first corporate sponsor, the Alcoa Corporation. Pregracke started cleaning up the river in 1997, collecting 45,000 pounds of debris from its shores. In 1998, Pregracke established his nonprofit organization, Living Lands and Waters (LLW), dedicated to cleaning up the Mississippi River.

Since its establishment, LLW has removed 4 million pounds of trash from the Mississippi and its tributary rivers Missouri and Ohio. The cleanup efforts are staffed primarily by community volunteers. Their annual haul of trash includes items such as refrigerators, tires, bowling balls, baby dolls, and Styrofoam. In August 2005, Pregracke and his crew provided assistance with cleanup and rebuilding efforts in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina struck the area. In 2007, the MillionTrees Project was established to encourage the planting and growth of 1 million native hardwood nut-bearing trees throughout the Midwest.

Chad Pregracke, founder of Living Lands and Waters, sits atop on of his river clean-up barges.

KUNI TAKAHASHI/KRT/Newscom

Pregracke is modest in describing his life’s mission:

I’ve been on a mission to clean up the rivers. It was a simple concept then and it’s a simple concept now, but doing it has been far from simple or easy. I realize that we’re not solving all the problems or necessarily saving America’s rivers—we’re simply doing our part, just as I hope you’re doing yours. (Pregracke and Barrow 2007:282–83)

We all make a difference, even if we don’t intend to, and it’s either negative or positive. My question to you is, how big a difference do you want to make? I can’t say how big a difference I’ve made or will continue to make, but I know this—I will plant a lot of trees and leave a cleaner river. (Pregracke and Barrow 2007:288)

For his work, Pregracke was named 2013 CNN Hero of the Year. For more information about Living Lands and Waters, visit the organization’s website at http://www.livinglandsandwaters.org.

Radical Environmentalists

Rik Scarce (1990) explains that radical environmentalists want to preserve our biological diversity. This isn’t just a question of preserving the living things in our ecosystem, such as plants and animals; nonliving entities such as mountains, rivers, and oceans must also be protected. Radical groups confront problems through direct action, such as picketing an office building, breaking the law, or performing acts of civil disobedience. Other radical environmentalists may destroy machinery, property, or equipment used to build roads, kill animals, or harvest trees. Most “eco-warriors” act on their own and without the leadership of an organizational hierarchy.

Scarce (1990) says radical environmentalists adopt lifestyles that have minimal impact on the environment: they don’t own cars, they adopt vegetarian diets, and they avoid occupations that involve the destruction of the environment. Although they are committed to their issues, radical environmentalists recognize that on their own, they will never be able to end the practices they protest. Their actions usually attract media attention, creating a groundswell of public support for their particular issues. Or their actions are done in concert with mainstream efforts; for example, radicals might stage tree sittings in Oregon to delay the cutting of timber until courts can hear a more mainstream group’s request for injunction.

Tree sitting is a form of protest targeting timber companies at the point of production, slowing or even stopping tree cutting. Scarce (1990) explains how tree sitters make their protest in areas with active cutting, finding and choosing trees that will make the right statement. The trees they choose are the tallest, most impressive, and clearly visible from a road, or those that overlook a recently cut area. Although we may think of tree sitting as a lonely activity, tree sitters require a support group for assistance, food, and clothing, including the hauling of waste (including human) from the site. The group will carry about 250 pounds of gear and provisions—food, water, clothing, and platform materials—as far as 10 miles to their intended site. Suspended about 80 to 150 feet off the ground, the 2.5- by 6-foot wooden platform becomes the tree sitter’s home for days, weeks, or months. Julia “Butterfly” Hill sat in a 600-year-old California redwood tree for 738 days, withstanding eviction threats and legal action from the Pacific Lumber Company, which owned the tree. Tree sitting has been effective in bringing public and media attention to the practices of timber and logging companies and in rallying support for the tree sitter’s message. In several cases, agreements have been made with lumber companies to divert logging to other areas or to pursue viable logging programs.

Is Your School Green?

Several hundred green U.S. elementary and secondary schools have been established nationally, supported by state grants, legislation, and partners such as the Sierra Club and the National Wildlife Federation. Schools like the Environmental Charter High School in Los Angeles and the Growing Up Green Charter School in Long Island City, Queens, New York, offer students more than an environmental issues curriculum. These private, charter, and traditional public schools have adopted a focus that goes beyond the environment, addressing politics, social justice, environmental careers, social activism, and community involvement (Navarro and Bhanoo 2010). In 2012, New York City instituted a school composting program for 230 school buildings in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. In addition to creating composting material for farmers and local landscapers, the program creates cost savings (reducing the amount of food that goes to waste) and helps develop a new generation of conservationists (Baker 2014).

“Universities are huge institutions with huge carbon footprints, but they are also laboratories for concepts of sustainability,” says Michael Crow, president of Arizona State University (Deutsch 2007:A21). Colleges and universities are taking the environmental lead by constructing green buildings, purchasing alternative energy, incorporating local and sustainable food products, and investing in efforts to make campuses carbon neutral. Their efforts include the following (Deutsch 2007; Lipka 2006):

- Bowdoin and Evergreen State Colleges purchase 100% of their energy from renewable sources or pay for energy offsets from solar or wind power.

- Arizona State University distributes free bus passes to every student, employee, and faculty member.

- Dickinson College students operate an organic garden, using some of the produce in their campus dining hall.

- Students at Central Oregon Community College and the University of Kentucky voted to pay additional fees to cover their institutions’ clean-energy purchases.

- University of California–Irvine, University of Massachusetts–Amherst, Montana State University, and Eastern Tennessee State University are just some of the schools that have established a local chapter of the Real Food Challenge, an organization that promotes just and sustainable food systems on college campuses and in their communities.

Crow was among the first university presidents who signed the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. The presidents acknowledge their role in leading environmental responsibility in their campuses and broader communities. The commitment, signed by more than 600 college and university presidents, includes a pledge to develop and implement a plan to achieve carbon neutrality on their campuses. Ninety college dorms are certified in Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), the national standard for green design (Wilson 2009).

Writer Sara Lipka (2006) portrays college students as the “watchdogs for sustainability.” She explains,

Armed with Internet research, they are investigating institutional operations like energy use, food purchasing, investments, transportation, and waste disposal. They are pushing administrators to approve new projects and set higher goals for sustainability. National networks are helping students share strategies with one another and organize sophisticated, often successful proposals for campus innovations and reforms. (Lipka 2006:11)

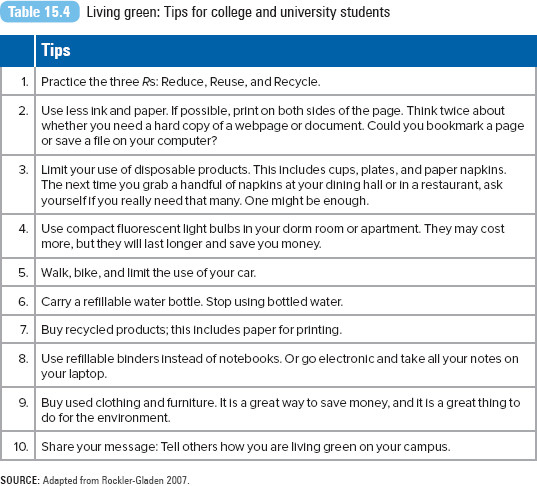

Similar environmental programs have been established in elementary and secondary schools across the country. To learn more about what you can do to protect the environment, refer to Table 15.4.

SOURCE: Adapted from Rockler-Gladen 2007.

Sociology at Work

Research

Tiffany Fackler—Class of 2009

Undergraduate Major: Sociology, Anthropology

Undergraduate Minor: Human Services

As discussed in Chapter 4’s Sociology at Work feature, your coursework in research methods and statistics provides you with important data analytic skills. Such skills are requisite for occupations such as market or survey research. Many organizations and businesses routinely require data collection and analyses as part of their operations. Employees may be responsible for all or part of the research process—data collection, analysis, and reporting.

As an undergraduate, Tiffany Fackler completed an internship related to law enforcement. Her experience eventually led her to her current position as a criminal analyst for several state agencies.

Daily I am working with law enforcement agents both tactically and strategically to ensure that they are being provided accurate information regarding subjects and subject matter. I run information through, pull from and input data into databases, create link analysis charts, write intelligence reports and assist with making connections among individuals conducting illegal activities.

Sociology is an important part of Tiffany’s work life.

Utilizing sociology at work occurs even when I am not realizing I am using it. The job requirements in their nature require the use of sociology. Every day there is analysis of social behavior, where it comes from, the development of social behavior, organizations and institutions. Within the law enforcement and intelligence realm there are always changes occurring with social order. In order to appropriately report on social order and disorder, utilizing empirical investigation and critical analysis is imperative.

She says, “I truly believe that regardless of what position you hold after graduation, sociology can always be utilized.”

Tiffany’s primary source of career information was her adviser, though she also utilized her university’s career services office and reviewed résumé writing for federal employment. She is currently enrolled in a master’s program in leadership and business ethics.

Chapter Review

- 15.1 Explain the relationship between human activity and environmental problems

Daily human activity, economic development, cultural values, social class, and technology all affect the health of the environment. Environmental sociology considers the interactions between our physical and natural environments and our social organization and behavior.

- 15.2 Review the different sociological perspectives on environmental problems

From a functionalist perspective, agriculture, industrialization, and related technologies may have improved our quality of life, but they have also led to waste, pollution, and the destruction of natural resources. Conflict theorists suggest that environmental problems are created by humans competing for power, income, and their own interests in a capitalist system. Feminists argue that a masculine worldview is responsible for the domination of nature, women, and minorities. One strand of thought, ecofeminism, believes that men are the primary culprits in the exploitation of animals and the environment. Interaction theorists address how environmental problems are created, defined, and often contested.

- 15.3 Discuss climate change and global warming

The terms are often used interchangeably but are two different environmental events. Climate change refers to any significant change in the measures of climate (temperature or precipitation) lasting for an extended period of time. Global warming refers to the ongoing rise in the global average temperature near the Earth’s surface.

- 15.4 Summarize federal and state responses to environmental problems

Efforts in land conservation and wilderness protection seem to be successful largely because of federal protection policies and legislation. Examples, among many, are the Wilderness Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

- 15.5 Compare the first wave and second wave of environmental interest groups