Chapter 14 Urbanization

Learning Objectives

- 14.1 Define demography

- 14.2 Compare the processes of urbanization and suburbanization

- 14.3 Explain how a population is affected by its age distribution or ethnic composition

- 14.4 Summarize how the sociological perspectives explain urbanization and its related social problems

- 14.5 Analyze the pros and cons of gentrification

- 14.6 Describe the sustainable community movement

Cities have always maintained an allure of better living and opportunities. But an examination of our cities and their surrounding areas reveals a “profound duality” (Stanback 1991). Although our urban areas are shining examples of economic and social progress, they also harbor significant social problems such as poverty, crime, crowding, pollution, and collapsing infrastructures. Moreover, opportunities and resources are unevenly distributed in cities: Some neighborhoods have safer streets and better services and may offer a better quality of life than others do (Massey 2001). “Cities in different countries with different socioeconomic and political systems often face quite similar problems, although their scales, trends, or causes differ from place to place” (Kim and Gottdiener 2004:172).

Though it is still referred to as America’s Motor City, Detroit has a new nickname, “most miserable city” (Badenhausen 2013). The colossal economic failure of Detroit has brought renewed attention to the relationship between economic, social, and political forces and the health and structure of urban spaces. Detroit was an industrial giant in the beginning of the 20th century, headquarters for automobile giants General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. The city’s population peaked in the 1950s at 1.8 million. But as housing developments were established in Detroit’s suburban areas, residents began to flee. Automobile manufacturing expanded into different states, and as competition grew with Japanese automakers, the three automakers collectively lost 40% of the U.S. automobile market share. Rising and persistent unemployment was followed by declining tax revenues, declining property values, and urban blight. The Great Recession of 2007–2009 crushed the city’s hope for an economic recovery. In 2014, Detroit’s population was estimated at 700,000. In 2013, the city filed for bankruptcy, seeking protection from an $18 billion debt, the largest filing in U.S. history (Davey and Williams Walsh 2013).

Before we begin our study of urbanization and its related social problems, we will first review two sociological fields of study. Both remind us that cities don’t just happen overnight; rather, social and demographic factors help shape our urban areas and their problems. Our urban areas are produced by economic, political, and cultural forces operating at international, national, and local levels (Kim and Gottdiener 2004).

Urban Sociology and Demography

In the 1920s, sociologists from the University of Chicago examined their city and the impact of city life and its problems on its residents. Their research provided the basis for urban study and for understanding the determinants of urbanization. Urban sociology examines the social, political, and economic structures and their impact within an urban setting. Rural sociology is the study of the same structures within a rural setting.

The first studies on urbanization or urban sociology adopted a functionalist approach, comparing a city to a biological organism. The growth of a city was likened to the development of a social organism, with each part of the city serving a specific and necessary function. A city’s core, for example, served as its business or industrial center; and areas outside a city were reserved for residential or commuting activity. Out of the Chicago School of Sociology came two dominant traditions in urban studies, one focusing on human ecology (the study of the relationship between individuals and their physical environment) and population dynamics and the second focusing on community studies and ethnographies (Feagin 1998a).

Although this chapter’s primary focus is on urban problems, an essential part of urbanization is the number of residents in an area, its population. The second sociological field we will rely on is demography: the study of the size, composition, and distribution of human populations (see also Chapter 6). Demography isn’t just about counting people. Demographers analyze the changes and trends in the population. Their work begins with two fundamental facts: We are born, and then we die. Recall how in Chapter 10, “Health and Medicine,” we reviewed how two demographic elements, fertility and mortality, are determined by biological and social factors.

An additional demographic element is migration, the movement of individuals from one area to another. Migration is distinguished by the type of movement: immigration is the movement of people into a geographic area; emigration is the movement of people out of a geographic area. Domestic migration (the movement of people within a country) plays a large role in the population redistribution in the United States (Perry 2006). In the United States, about 35.9 million people moved between 2012 and 2013 to a different residence, the majority to the same county in their state (Ihrke 2014). People migrate to pursue employment opportunities, to be closer to family, to find a more temperate climate, and to seek the opportunity of a better life. Most movers have housing-related reasons: They move to a new, better, or more affordable home or apartment (Schachter 2004).

The Processes of Urbanization and Suburbanization

Urbanization, the process by which a population shifts from rural to urban, took off in the latter half of the nineteenth century (Williams 2000). Urbanization in the United States, as in other developed countries, was closely linked with economic development and industrialization. The U.S. economy in the middle of the 19th century was divided: the northern economy was characterized by a mixture of family-based agriculture, commerce, finance, and an increasing industrial base, whereas the southern economy remained dependent on agriculture (Gordon 2001). But as the industrial economy began to grow in the North and extended into the Midwest, thousands of people were attracted to these emerging urban centers, drawn by the promise of work in factories and mills (Williams 2000). Also contributing to early urban growth was the immigration of Europeans and the migration of rural Blacks and Whites from the South to northern and midwestern urban areas (Dreier 1996).

The process of global urbanization is described in waves. The first wave occurred in North America and Europe from 1750 to 1950 (United Nations Population Fund 2007), closely linked with industrialization and economic development (Kim and Gottdiener 2004). This wave involved a few hundred million people and produced urban industrial societies that now dominate the world (United Nations Population Fund 2007).

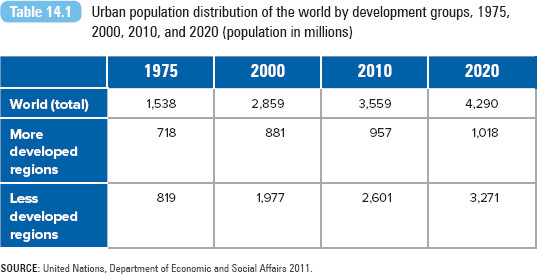

The second wave of urbanization took place during the past half-century in developing countries. Some have referred to the shift as overurbanization, the process where an excess population is concentrated in an urban area that lacks the capacity to provide basic services and shelter. Overurbanization is characterized by a lack of employment, housing, and education or health infrastructures for an area’s residents (Kim and Gottdiener 2004). This second urbanization wave is problematic because it involves large populations of poor people—instead of hundreds of millions as in the first wave, the second wave involves billions residing mostly in Africa and Asia (United Nations Population Fund 2007). Refer to Table 14.1 for a comparison of urban populations between developed and less developed regions.

After World War II, the United States experienced another significant population shift: suburbanization. Although suburbanization has come to represent the outward expansion of central cities into suburban areas (N. Smith 1986), increasing population growth rates away from city centers, it has also been linked with two additional population shifts: from the Snow Belt (industrial regions of the North and Midwest) to the Sun Belt (South and Southwest) and from rural to metropolitan areas (Dreier 1996). Though many factors contributed to suburbanization, the key players were government leaders and their policies. The U.S. Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949, which encouraged construction outside city boundaries and made home purchasing easier through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veterans Affairs home mortgage loan programs. The 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act, which established the modern interstate highway system, made rural areas more accessible. President Dwight Eisenhower, a chief proponent of the act, believed in the importance of the interstate highway system. Eisenhower (1963) declared,

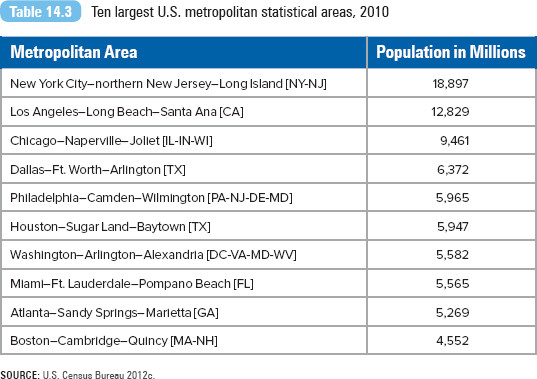

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 1995, 2012a.

More than any single action by the government since the end of the war, this one would change the face of America. . . . Its impact on the American economy—the jobs it would produce in manufacturing and construction, the rural areas it would open up—was beyond calculation. (pp. 548–49)

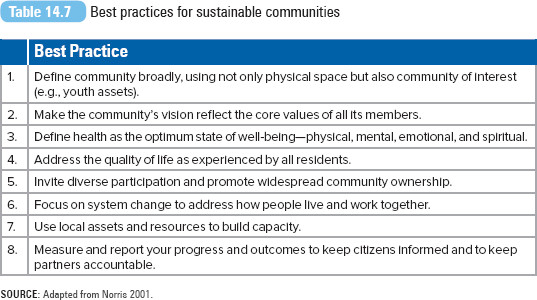

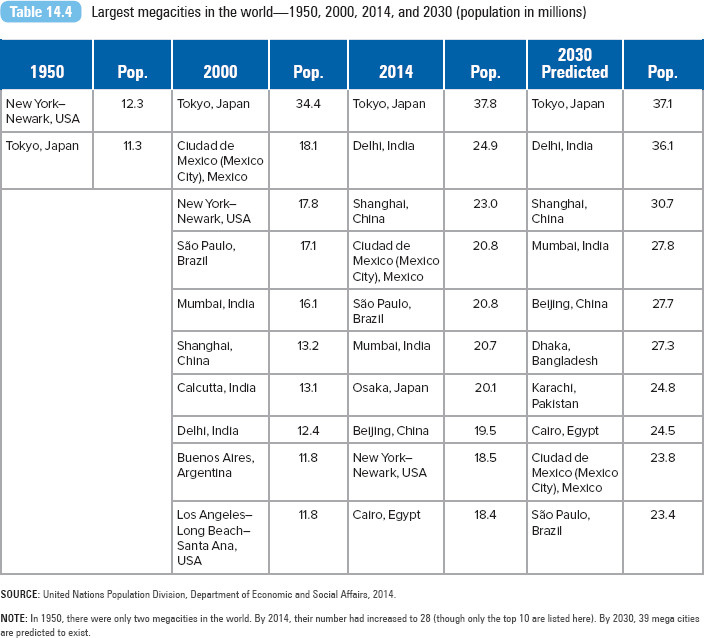

The U.S. Census Bureau defines an urban population as an area with 2,500 or more individuals. An urbanized area is a densely populated area with 50,000 or more residents, and a metropolitan statistical area is a densely populated area with 100,000 or more people. U.S. Census data indicate a rapid increase in the urban population, especially after World War II (Table 14.2). For 2010, the three largest metropolitan statistical areas were New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago (U.S. Census Bureau 2012a). The largest area was New York City–northern New Jersey–Long Island, with 1,889,700 people. A complete list of the 10 largest metropolitan statistical areas is presented in Table 14.3. The New York–Newark area remains one of the world’s largest megacities (10 million residents or more). Refer to Table 14.4 for the complete list of megacities.

Population Growth and Composition

Changes in the fertility, mortality, and migration rates of a population affect its composition and its biological and social characteristics. For example, age distribution, the distribution of individuals by age, is particularly important because it provides a community with some direction in its social and economic planning, assessing its education, health, housing, and employment needs. For example, the driving behavior of the members of the Millennial generation (those born between 1983 and 2000) may change the future of transportation (U.S. PIRG Education Fund 2013). Millennials are the first generation to embrace mobile Internet technologies, which is changing the way young Americans relate to each other, but also changing the way they choose to live. They drive less than older generations and are more likely to adopt non-driving forms of transportation. In comparison with Baby Boomers and Generation X’ers, Millennials are twice as likely to express a desire to live in a walkable urban area (U.S. PIRG Education Fund 2013).

SOURCE: United Nations Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014.

NOTE: In 1950, there were only two megacities in the world. By 2014, their number had increased to 28 (though only the top 10 are listed here). By 2030, 39 mega cities are predicted to exist.

Demographers have noted how the ethnic composition (the composition of ethnic groups within a population) affects social and human services. In 2007, the U.S. Census Bureau announced that one in three Americans were ethnic minorities, about 101 million. Roberto Suro and Audrey Singer (2002) explain how the Latino population has spread out further and faster across the nation than any previous wave of immigrants. In 2012(b), the U.S. Census Bureau announced that Hispanics were the largest and fastest-growing minority group in the United States, numbering 52 million in 2011.

Housing, education, health, and public transportation demands are affected by the rate of Latino population growth. For example, cities and areas with large established Latino communities (e.g., New York, Chicago, Miami, Southern California) should prepare for a growing Latino population characterized by low-wage workers, large families, and significant numbers of adults with little English proficiency (Suro and Singer 2002). In California, researchers from the University of California–Los Angeles Medical School recommended shifting health care services because Hispanic Californians tend to live longer than non-Hispanics and are less likely to die from heart disease or cancer (Murphy 2003).

The increasing number of ethnic Americans and their age distribution has caught demographers’ attention. When data for the 2007 U.S. Census were announced, researchers noted that younger Americans were more ethnically diverse than were older generations—the average age of non-Hispanic Whites was 40.5 years, whereas among Hispanics, the average age was 27.4 years. This age gap may lead to competing political and social agendas. Communities may be divided between older Americans advocating social security, lower taxes, and better health care and younger ethnically diverse Americans demanding better education, jobs, and social services (Roberts 2007).

Sociological Perspectives on Population and Urbanization

Functionalist Perspective

Early functionalists were critical about the transition from simple to complex social communities. Émile Durkheim described this transition as a movement from mechanical solidarity to organic solidarity. Under mechanical solidarity, individuals in small simple societies are united through a set of common values, beliefs, and customs and a simple division of labor. Most individuals are engaged in the same type of economic activity or labor. In contrast, Durkheim argued, organic solidarity is the result of increasing industrialization and the growth of large complex societies, where individuals are linked through a complex division of labor. Under organic solidarity, individuals begin to share the responsibility for the production of goods and services, each with a specific role in production. New relationships are created according to what people can do or provide for each other. For example, most of us do not raise the food for our meals. We depend on others to grow, harvest, deliver, and sell our food and groceries, and others depend on us for our specific labor activity. Durkheim believed that as a result of industrialization, the social bonds that unite us will eventually weaken, leading to social problems.

Although industrialization and urbanization have been functional, creating a more efficient, interdependent, and productive society, they have also been problematic. Because of the weakening of social bonds and an absence of norms, society begins to lose its ability to function effectively. As our social bonds with each other have loosened, our sense of obligation or duty to one another has declined.

Urbanization can lead to social problems such as crime, poverty, violence, and deviant behavior. Functional solutions to these problems may encourage reinforcing or re-creating social bonds through such existing institutions as churches, families, and schools or instituting societal changes through political or economic initiatives. For example, under mechanical solidarity, the strong social bonds linking an individual to society (through one’s family and friends) deter criminal behavior. A person would not think of committing a criminal act because it would be inherently wrong or would harm the individual’s relationship with other members of society. Under organic solidarity, criminal laws, police, and prison systems serve as formal structures to deter criminal activity.

Chinese Urbanization

Taking a World View

Global Urbanization and Population Growth

In its 2007 report, the United Nations Population Fund predicted that “at the global level, all future population growth will [thus] be in towns and cities” (p. 6). More than half the world’s population was living in urban areas by 2008, approximately 3.3 billion individuals. In contrast, the world’s rural population will decline by about 28 million between 2005 and 2030. Urban population growth is expected to occur in developing nations such as Africa and Asia, with slower expansion expected in Latin America and in the Caribbean. Most of the growth is attributed to natural increases (more births than deaths) rather than migration. In the developed world, the urban population is expected to grow very little, from 870 million to 1 billion.

There are many negative consequences of urban population growth for individuals, nations, and the world: increased demand for social and human services; increased economic and political burdens, particularly for poorer developing countries; and global environmental degradation (Desai 2004). Some segments of the population are more vulnerable than others are. By 2030, 60% of all urban dwellers will be younger than age 18. Cities need to ensure that appropriate levels of basic services, education, housing, and medical care are available for these youth; if not, life on these urban streets will threaten the quality of youths’ health, education, safety, and future (United Nations Population Fund 2007).

Despite its dire message, the United Nations Population Fund (2007) concludes, “Urban and national governments, together with civil society, and supported by international organizations, can take steps now that will make a huge difference for the social, economic and environmental living conditions of a majority of the world’s population” (p. 3). Suggesting the need for more proactive and creative approaches, the organization recommends strategies to improve the social conditions of the poor, promote gender equality, and ensure environmental sustainability. A major component of the recommendations is to empower women and increase the level of reproductive health services available to families, believing that these interventions will influence individuals’ fertility preferences (the number of children and the timing of births) and their ability to meet them. Such a strategy “empowers the exercise of human rights and gives people greater control over their lives” (United Nations Population Fund 2007:70).

In its 2007 report, the United Nations Population Fund predicted that “at the global level, all future population growth will [thus] be in towns and cities” (p. 6). Urban population growth is expected to occur in developing nations such as Africa and Asia, with slower expansion expected in Latin America and in the Caribbean.

B MATHUR/REUTERS

Conflict and Feminist Perspectives

Since the late 1960s, a new perspective on urban study has emerged. Referred to as the critical political-economy perspective or socio-spatial perspective, this approach uses a conflict perspective to focus on how cities are formed on the basis of racial, gender, or class inequalities. From this perspective, cities are shaped by powerful social and political actors from the private and public sectors, working within the modern capitalistic structure (Feagin 1998b). Social problems are natural to the system, rising from the unequal distribution of power between politicians and taxpayers, the rich and the poor, the homeowner and the renter, or Whites and Blacks.

Residential segregation is defined as the neighborhood clustering or separation of groups by racial, ethnic, or economic characteristics within a geographic area. Residential segregation is a form of social organization that enables differential access to resources and opportunities, such as public services, schools, and employment opportunities (Dickerson 2008), advantaging one group over another. From this perspective, residential segregation is not accidental, but is the product of institutional discrimination, city governments, zoning laws, mortgage redlining policies, tax bases, and school systems that perpetuate racialized socioeconomic inequalities (Hanlon 2011; Judd and Swanstrom 2004).

Sociologists offer three primary explanations for the persistence of Black–White segregation: housing market discrimination, differences in socioeconomic status, and preferences for specific neighborhood racial composition (Massey and Denton 1993; Charles 2003). Martha Mahoney (1997) explains:

For whites, residential segregation is one of the forces giving race a “natural” appearance: “good” neighborhoods are equated with whiteness, and “black” neighborhoods are equated with joblessness. This equation allows whiteness to remain a dominant background norm, associated with positive qualities for white people, at the same time that it allows unemployment and underemployment to seem like natural features of black communities. (p. 330)

Within this tradition, scholars also examine the role of capitalism and capitalists in shaping cities (Feagin 1998b). Land-use decisions are made by politicians and businesspeople (Gottdiener 1977), real estate developers and financiers (Molotch 1976), or coalitions between public officials and private citizens (Rast 2001). Joe Feagin (1998b) presented a theory of urban ecology that accented the role of class structure and powerful land-oriented capitalist actors in shaping the location, development, and decline of U.S. cities. Land speculators shape the internal structure of cities by identifying and packaging particular parcels of land for business or residential use. As Feagin (1998b) describes it,

powerful land-interested capitalists have contributed substantially to the internal physical structure and patterning of cities themselves. The central areas of cities such as San Francisco have been intentionally remade, in the name of private profit, by combinations of speculators and other capitalists, such as developers. (p. 154)

Although women play a pivotal role in urban life, theories about urbanization have taken a gender-blind approach (Women’s International Network News 1999). Urban studies have not systematically considered cities as sites of institutionalized patriarchy (Garber and Turner 1995) and have not legitimately considered the role of women in urban development. In the 1880s, women activists advocated quality housing, public health and sanitation services, food safety, and health and social services in emerging cities (Parker 2011). Feminist urbanists have argued for the development of a comprehensive field of theory and research that acknowledges the role of women in urban structures (Masson 1984).

By incorporating feminist theory in patriarchy and urban studies, we can understand an additional dimension of urban life, namely the complex ways in which cities reproduce and challenge patriarchy (Appleton 1995) and the problems this creates. Cities are places where gender is experienced and constituted. As Judith Garber and Robyne Turner (1995) explain,

urban environments are constructed around the delivery of public services and the development of policies. These shape women’s ability to cope with complex urban locations, largely through the responsiveness of public and private organizations to the needs of diverse groups of women and children. (p. xxiii)

Turner (1995) argues that the living conditions of lower-income, inner-city women have been affected by the economic restructuring of cities and the patterns of downtown development. Woman-headed households increasingly make up the majority of inner-city households. Turner explains that although low-income women may find inner-city housing less costly and more accessible than housing in the suburbs is, urban living also presents a unique set of challenges in transportation, housing, employment, services, and safety. Inner-city women have less control over their living situations than suburban women do. City development decisions are made by those in power, often men, whereas the decisions affect women, the young, and the elderly. Turner (1995) concludes, “It is important to recognize the implications for women, as the heads of households, in the debate on economic restructuring, land based economies, and the portrayal of political power” (pp. 287–88).

Suburban Discrimination

Interactionist Perspective

Georg Simmel ([1903] 1997) was the first sociologist to explain how city life is also a state of mind. In his 1903 essay, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” Simmel described how life in a small town is self-contained; interactions with others are routine and rather ordinary. But a city’s economic, personal, and intellectual relationships cannot be defined or confined by its physical space; rather, they are as extensive as the number of interactions between its residents. City dwellers must interact with a variety of people for goods and services and for personal and professional relationships. City living stimulates the intellect and individuality of its residents (Karp, Stone, and Yoels 1991). Elijah Anderson (2004) described how urban public settings (like markets, restaurants, parks), which he referred to as cosmopolitan canopies, encourage people to treat others with a certain level of civility or at least simply to behave themselves. These canopies “allow people of different backgrounds the chance to slow down and indulge themselves, observing, pondering . . . testing or substantiating stereotypes and prejudices” (p. 21).

But how well are city dwellers connected with their neighbors? The answer is that they may not be as connected as Simmel or Anderson predicted. The way a city is constructed might actually interfere with social interaction. Our dependency on automobiles compartmentalizes neighborhood relations (we only know neighbors on our block or street) and interferes with street life (no space for ball games, block parties, bike riding, and joggers) (Gottdiener 1977). Home and residential designs limit our face-to-face contact with our neighbors. Without porches, there is no place to sit out front and visit with one’s neighbors; without sidewalks or local parks, families find it less appealing to take walks around their neighborhood and less easy to meet with neighbors.

Does urban living (and the preoccupation with personal technology) unite or divide residents?

© Shaun Lombard/iStock

Tridib Banerjee and William Baer (1984) discovered that how we define our cities is linked to what we value or use within them. What goods and services do people use in their community? Is it the coffee shop, the local dry cleaner, or the neighborhood grocery store? Or is it the local park, the bicycle lanes, or the athletic center down the street? The researchers asked residents of several Southern California cities to draw maps of their residential areas and discovered that illustrations by middle- and upper-income individuals contained more details and area than illustrations by lower-income people did. Upper-income groups included amenities such as tree-lined streets, wooded areas, and golf courses, whereas middle- and low-income groups included commercial and retail locations, such as gas stations, discount stores, or drug stores. Corporate symbols were commonly used to define landmarks in middle- and low-income illustrations. Banerjee and Baer concluded that income was the single most important variable in explaining the quality of residential experiences and residents’ judgments about what constitutes a “good place” to live.

Based on his examination of the transformation of European cities from industrial centers to recreational destinations, Mathis Stock (2006) concluded that a city may be defined by conflicting constituent groups (residents vs. tourists) and the vastly different experiences of the city they cohabit. The transformation of cities such as Paris, Venice, and Florence into tourist destinations is often intentional, with city leaders and businesses embracing the symbols of tourism—the language, images, practices, and customs—in their cities. To entice visitors to their city, they promote their city’s annual festivals and package them along with well-known cultural and historical sites as part of a cultural heritage experience. This transformation has its detractors, who, though acknowledging the revenue benefit of tourism, question whether this process has stripped these historical European cities of their authentic identities and subordinated native residents as a result. In 2009, Venetians held a mock funeral as a sign of protest for their city, complete with a fake coffin floating down the Grand Canal. The number of historic center residents dropped from 74,000 in 1993 to 60,000 in 2009; the decline is blamed on rising rents and increasing numbers of tourists that pushed locals onto the mainland (Donadio 2009).

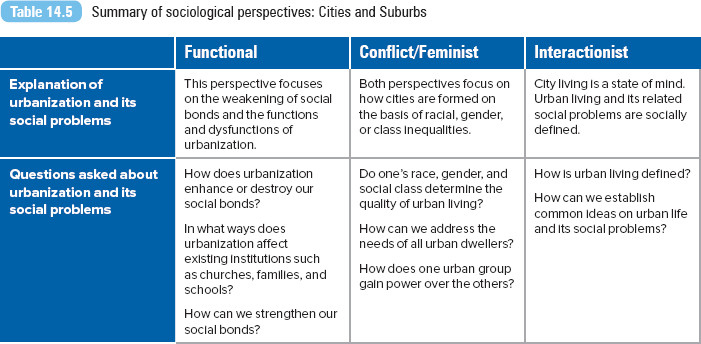

For a summary of the different sociological perspectives, see Table 14.5.

Social Capital

The Consequences of Urbanization

Along with suburbanization came the decentralization, some may even say the demise, of U.S. cities. Inner cities became repositories for low-income individuals and families, as the suburbs enjoyed higher tax bases and fewer social programs (Massey and Eggers 1993). Researchers have suggested that the poor economic outcomes of racial minorities, particularly African Americans, are partly the result of patterns of housing prejudice and discrimination that have prevented minority groups from moving at the same pace as the suburbanization of employment (Massey 2001; Pastor 2001). According to Douglas Massey and Mitchell Eggers (1993),

the simultaneous proliferation of poverty and affluence created a situation in which social problems among those at the bottom of the income hierarchy multiplied rapidly at a time when more and more people had the means to escape these maladies. (p. 313)

Many of the social problems we discuss in this text seem to be magnified in urban areas. In this next section, we will review specific social problems plaguing urban areas: quality housing, crowding, homelessness, gentrification, and urban sprawl and transportation.

Urban Living Environment

Many aspects of urban life—quality of air and drinking water, sanitation and fire services, and the availability and affordability of health care—have well-established connections to the health of urban dwellers (Cohen and Northridge 2000). For example, India’s cities are characterized by “teeming hovels of dirt and garbage, overcrowded and noisy lanes, and proliferation of slums” (Siddiqui and Pandey 2003:590). India’s urban centers are home to more than a quarter of India’s total population. Deprived of the basic amenities of water, sewage, and waste disposal facilities, India’s urban residents are subject to unsafe and unhealthy living conditions.

One area that is often overlooked is the quality of housing. Substandard housing (homes with severe or moderate structural problems such as malfunctioning plumbing or heating) is a major U.S. public health issue (Krieger and Higgins 2002), particularly among urban dwellers and people of color. Housing quality has been associated with morbidity from infectious diseases, chronic illnesses, injuries, poor nutrition, and mental disorders (Krieger and Higgins 2002). Disparities in quality housing have remained unchanged since the 1970s. Approximately 7.5% of non-Hispanic Blacks and 6.3% of Hispanics live in moderately substandard housing compared with 2.8% of Whites (Jacobs 2011).

Interior residential density refers to the number of individuals per room in a dwelling. The criterion for crowding is more than one person per room in the household. In the United States, household crowding is more likely to be found among poor, immigrant, or urban families. Research indicates that children who live in more crowded homes have greater behavioral problems in the classroom. Crowding also leads to greater conflict between parents and children. In crowded homes, parents have been found to be more critical of and less responsive to their children (Evans, Saegert, and Harris 2001). Crowding is also related to infectious disease transmission such as tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases.

William Clark, Marinus Deurloo, and Frans Dieleman (2000) argue that household crowding is linked to inequalities in housing consumption. The researchers explain that the rising income of a large segment of U.S. society has led to increases in the overall quality of housing in the United States. But at the same time, growing income inequalities create affordability and crowding problems for very-low-income households. Affluent households demand better-quality and larger houses, increasing their consumption of livable space, pushing housing outside of inner-city boundaries. Clark et al. explain that as middle-class families move to the suburbs, they leave behind inner cities plagued with increased density and housing shortages.

Cities with large numbers of immigrants—such as those in such states as California, Texas, Arizona, and Florida—are especially subject to crowding. A study based in Southern California reveals that households of Hispanics who immigrated in the 1970s are 212 times more likely to be overcrowded than are those of earlier Hispanic immigrants or White immigrants (Myers and Lee 1996). Clark et al. (2000) also report that in metropolitan areas with high levels of recent immigration, overcrowding is higher than in nonimmigrant areas. Poor immigrant households experience the most crowding and have the most difficulty in transitioning to better, more affordable housing. Studies suggest that competition for housing in cities with many immigrants may increase the cost of housing and can lead to a housing squeeze. Cultural norms may also play a role in encouraging crowding among Hispanic immigrant homes.

Crowding is also a global issue, in countries experiencing rapid population growth. For example, the population of Lagos, Nigeria, has doubled over 15 years to 21 million (Rosenthal 2012). City residents typically live in apartments, 7- by 11-foot rooms described as “Face Me, Face You.” Up to 50 people may share a kitchen, toilet, and sink (Rosenthal 2012).

Overcrowding and Illness

Homelessness

By its very nature, homelessness is impossible to measure with 100% accuracy (National Coalition for the Homeless 2002). Most estimates are based on head counts in shelters, on the streets, or at soup kitchens. These estimates do not include those who live in temporary or unstable housing (e.g., those who move in with friends or relatives). Most public and private sources agree that the number of homeless people is at least in the hundreds of thousands, not counting those who live with relatives or friends (Choi and Snyder 1999). There are several national estimates of homelessness. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2014) estimated that 578,424 people were homeless on a given night. The majority (69%) were staying in residential (shelter) programs, while the rest (31%) were in unsheltered locations. Nearly one quarter of all homeless were children under the age of 18. About 37% of the homeless were families. For information about the U.S. homeless population, refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature.

Homelessness is impossible to measure with 100% accuracy (National Coalition for the Homeless 2002). This field researcher collects information from a homeless man.

Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Globally, the highest concentrations of homeless people tend to be located in urban settings and segregated in some of the traditionally poorest areas (Toro 2007). In contrast to the United States, European countries experience lower rates of homelessness because their social welfare system guarantees some level of income, health care, and housing for all citizens. Japan is facing a rapidly growing problem of homelessness because its welfare system is even more underdeveloped than that of the United States (Toro 2007).

Before the mid-1970s, the majority of the homeless were older, single males with substance abuse or physical or mental problems (Choi and Snyder 1999). Their individual disabilities or personal pathologies were likely to have caused their homelessness. Since the mid-1970s, however, the increasing number of homeless men, women, and families indicates that more than individual disabilities or personal characteristics are causing homelessness (Choi and Snyder 1999).

The U.S. Conference of Mayors (2013) identified several interrelated causes of homelessness for families and single adults: unemployment and lack of affordable housing. When asked what three things cities should do to address homelessness, the mayors identified more mainstream assisted housing, more or better-paying employment opportunities, and permanent supportive housing for people with disabilities.

Hiding Homelessness

Affordable Housing Shortage

Exploring social problems

Commuting

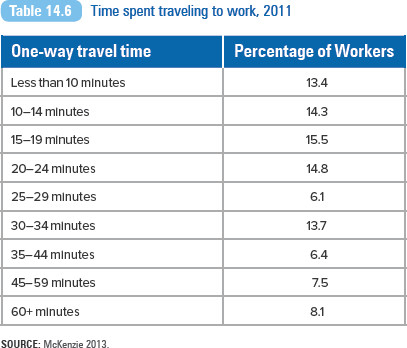

SOURCE: McKenzie 2013.

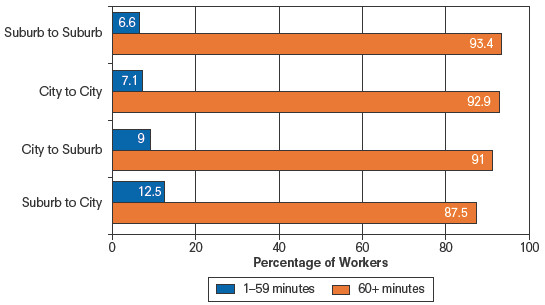

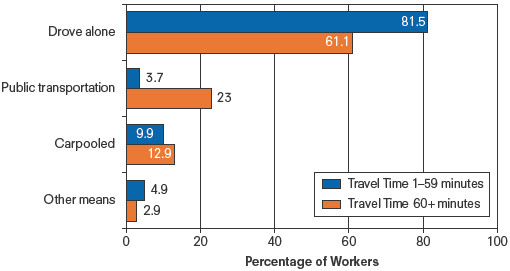

Figure 14.1 Residence-to-work pattern by commute time, 2011

SOURCE: McKenzie 2013.

Figure 14.2 Commute mode by commute time, 2011

SOURCE: McKenzie 2013.

What Do You Think?

The national average travel time to work (one way) was 25.5 minutes in 2011 (McKenzie 2013). Workers in the New York and Washington, DC, metro areas had the two longest travel times, 34.9 minutes and 34.5 minutes, respectively. The percentage of workers by one-way travel time is presented in Table 14.6.

Those who commuted from suburbs to a city for work were more likely to have a 60+ minute commute compared to other home/workplace categories (refer to Figure 14.1).

The mode of commuter transportation varied by time travel (refer to Figure 14.2). Workers commuting 60+ minutes or longer relied on carpools or public transportation more than workers with commute times under an hour. However, for both groups, driving alone was the most popular transportation mode.

How would you define a “long” commute? How important is it for you to live in close proximity to where you work (or go to school)?

Gentrification

In their report “Dealing With Neighborhood Change,” Maureen Kennedy and Paul Leonard (2001) reveal that gentrification, “the process of neighborhood change which results in the replacement of lower-income residents with higher-income ones, has changed the character of hundreds of urban neighborhoods in America over the last 50 years” (p. 1). Gentrification has occurred in waves: the urban renewal efforts in the 1950s and 1960s and the “back-to-the-city” movement of the late 1970s and 1980s. Gentrification is a global experience, with renewal efforts documented in Tokyo, London, Mexico City, Cape Town, Paris, Shanghai, and Sydney, as well as in many other countries and cities (N. Smith 2002). Gentrification continues today.

The researchers describe gentrification as a “double edged sword.” Officials and developers point to the increasing real estate values, tax revenues, and commercial activity that take place in revitalized communities. But is there a price for these capital and economic improvements? The most contentious by-product of gentrification is the involuntary displacement of a neighborhood’s low-income residents. No consistent data exist on the number of individuals who have been displaced through gentrification, yet the evidence suggests that where housing markets are tight (or limited), the amount of displacement is likely to be greater and the impacts on those displaced more serious (Kennedy and Leonard 2001).

Gentrification is most often associated with the disproportionate pressure it puts on marginalized poor, elderly, or minorities. The benefits of neighborhood revitalization are not equally distributed. Research reveals how gentrification is more economically successful in higher-income neighborhoods than in minority or low-income neighborhoods. Residents of higher-income gentrified neighborhoods experience greater integration and economic benefit than residents of low-income neighborhoods that gentrify (Hwang and Sampson 2014). For example, Richard Barrett and his colleagues (2008) reported a negative association between gentrification and the health of low-income residents. The researchers concluded that neighborhood economic vitalization encourages more expensive service providers to move into the neighborhood, thus disrupting or eliminating low-income residents’ access to low-cost health care. In a study of public education outcomes, Micere Keels, Julia Burdick-Will, and Sara Keene (2013) concluded that neighborhood revitalization had no effect on public school revitalization. The researchers found no significant difference in reading and math test scores between students enrolled in schools in gentrified neighborhoods compared to students enrolled in un-gentrified neighborhood schools. Their research casts doubt on the idea that low-income children will benefit from gentrification.

Though overall U.S. home values dropped between 2008 and 2011, values of homes in close-in or mixed-use neighborhoods held or increased their value. Demand for walkable urban places, with amenities of mixed housing types, destinations within walking distance, and public transportation options, increased above demand for homes in suburban areas with large home lots, ample parking, and driving as the primary means of transportation (Leinberger and Alfonzo 2012). In their analysis of sample neighborhoods in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, Christopher Leinberger and Mariela Alfonzo (2012) documented how residents of more walkable places have lower transportation costs and higher transit access, but higher housing costs. Residents of walkable places are more affluent than residents of places with poor walkability. Leinberger (2012) reported how similar class and cost patterns are present in other urban areas, such as Seattle, Washington; Denver, Colorado; Columbus, Ohio; and Atlanta, Georgia.

Urban Sprawl and Transportation

As urban areas spread out, they create a phenomenon referred to as urban sprawl. Urban sprawl began with land development after World War II. Sprawl is defined as the process in which the spread of development across the landscape outpaces population growth (Ewing, Pendall, and Chen 2002). Sprawl creates four conditions for an urban area: a population that is widely dispersed in low-density developments; rigidly separated homes, shops, and workplaces; a network of roads marked by huge blocks and poor access; and a lack of well-defined activity centers, such as downtowns or town centers (Ewing et al. 2002). Sprawl increases stress on urban livability as goods and services, along with economic and educational opportunities, become less accessible to inner-city residents (W. A. Johnson 2007; Powell 2007).

As sprawl increases, so do the number of miles traveled, the number of vehicles owned per household, traffic fatality rates, air pollution (Corvin 2001; Ewing et al. 2002), and, eventually, our risk of asthma, obesity, and poor health. On average, an American spends 443 hours per year behind the wheel (Crenson 2003). Public transportation usage is higher in metro areas. The New York–northern New Jersey–Long Island metro area had the highest percentage of workers who commuted to work via public transportation, 30.5% (McKenzie and Rapino 2011). New suburban residential developments don’t include sidewalks, and automobiles are needed to get from place to place.

Bicycles are ubiquitous in the Netherlands. There are an estimated 13 million bikes for the country’s 16 million residents. The Dutch have established a vast network of efficient and safe bike paths.

© pidjoe/iStock

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that urban sprawl increases our time on the road and decreases our time spent exercising, including walking, jogging, or riding a bike (Corvin 2001). Residents who live in spread-out areas spend fewer minutes each month walking and weigh about 6 pounds more on average than do those who live in densely populated areas (Stein 2003).

Americans spend more than 100 hours per year commuting to work (U.S. Census Bureau 2005). On average, an American worker’s daily commute is about 25 minutes (one-way commute time), and 75% of workers drive alone to work (McKenzie and Rapino 2011). Only 5% of commuters travel to work using public transportation. Residents from larger cities tend to have longer commutes: New York (38 minutes); Chicago (33 minutes); Newark, New Jersey (31 minutes); and Riverside, California (31 minutes) (U.S. Census Bureau 2005). Long commutes are also a global experience, particularly for poor disadvantaged workers. For example, commuting to Brazil’s largest industrial city, São Paulo, can take as much as four hours each way. São Paulo commuters are mostly minimum-wage laborers, commuting daily from their working-class poor suburbs to the city’s factories.

Car-free zones have also been embraced in several U.S. cities. New York, San Francisco, Kansas City, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, and El Paso have begun promoting car-free days in public parks, designated neighborhoods, and green spaces. Since 2010, the city of Los Angeles has sponsored CicLAvias, a car-free event spanning about 10 miles of city roads and streets. Advocates argue that these car-free practices promote family activities, active lifestyles, and closer communities (Wood 2007).

The overall reduction in driving, particularly by the Millennial generation, provides an opportunity to transform U.S. transportation policies. U.S. PIRG (2013) recommended increasing programs that could encourage Americans to drive less (public transportation systems, bicycling and pedestrian infrastructures) and creating a strategic plan for the repair and maintenance of existing transportation infrastructure (highways and bridges).

Magic Johnson Enterprises

In Focus

Living Car Free

North Americans are known for their love affair with, maybe even addiction to, their automobiles (Boddy 2000). Though the average number of persons per household has declined, 3.16 in 1969 to 2.66 in 2009, the number of vehicles has increased in the same time period from 1.16 to 1.92 (U.S. Department of Energy 2010). Despite rising fuel prices, U.S. housing and work patterns make it hard for suburban commuters to change their driving habits (Ohlemacher 2007). As of December 2014, the highest recorded average price for a gallon of regular gas was $4.43 in 2008.

However, many European countries and cities have found innovative and community-friendly ways to deal with gas prices consistently higher than $6.00 per gallon. For example, most of the 4,700 residents of Vauban, Germany, live car free. The rate of Vauban car ownership is 150 per 1,000 inhabitants compared with 640 per 1,000 residents in the United States. How does Vauban do it? Extensive city planning and innovative public policy. The city was built with an extensive system of bike paths and few parking spots. Parking spots for vehicles are available in a garage at the edge of the community for €17,500 (more than $20,000 per year). Vauban city planners have also encouraged residents to use public transportation such as tramways and buses. Many of the city’s streets were designed to be too narrow for cars (de Pommereau 2006).

In 2007, the city of Paris introduced Vélib’, a self-service bicycle transit system. From more than 700 locations throughout the city, individuals can rent bikes by the hour. There are 230 miles of cycling lanes in Paris.

Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz

Car use is discouraged in many different ways throughout the world. In Germany, there is a yearly car tax based on the automobile engine size—the bigger the engine, the higher the tax. Several European cities maintain fleets of bikes for public use to encourage bike riding as a transportation alternative. European Union countries, such as France, Italy, and Germany, have closed off parts of their city centers to cars for a day or permanently. In 1983, Bogotá, Colombia, initiated a program called ciclovía (bike path). Designated streets are closed to cars every Sunday, encouraging residents to jog, walk, or ride their bikes on the streets and revitalizing their neighborhoods as a result. One and a half million people are said to turn out for the Sunday ciclovía (Wood 2007).

Voices in the Community

Magic Johnson

Since his retirement from the Los Angeles Lakers, Earvin “Magic” Johnson has become a commercial developer opening state-of-the-art multiplex theaters including restaurants, retail, personal service, and Starbucks locations. Johnson’s company, Magic Johnson Enterprises, specifically targets business opportunities in minority inner-city and suburban neighborhoods.

At the opening of a 12-screen multiplex, the Magic Johnson Theatres, in South Central Los Angeles, Johnson was confident that such a business would succeed in inner cities because African Americans make up about 13% of the moviegoing audience (Dretzka 1995). Johnson said,

We’re the No. 1 movie goers of any (minority) group but you can’t find any theaters in your neighborhood. That’s why our theaters are doing so much business. We have great numbers, and for everybody in the neighborhood, it means more to them than just a theater. It’s a pride situation, bringing the community together. (quoted in Dretzka 1995:1)

Since retiring from professional basketball, Magic Johnson has become a commercial and real estate developer in minority inner-city and suburban neighborhoods.

© EdStock/iStock

The Magic Johnson Theatres cost an estimated $11 million and feature an art deco lobby with a large concession stand and a two-level parking garage. The Johnson Development Corporation has also opened theaters in Atlanta, Houston, Cleveland, and Harlem. The five theater complexes grossed $30 million in revenue in 2002 (Johnson 2003).

Johnson brought his understanding of the inner-city community to the business. In his movie concessions, knowing that inner-city children grew up drinking Kool-Aid, Johnson sells flavored sodas. “Used to be we couldn’t afford to go to dinner and the movie afterward. I told Loew’s [his theater partner], ‘Black people are going to eat dinner at the movies,’” says Johnson (quoted in Wilborn 2002). As a result, in addition to hot dogs and popcorn, the concessions sell chicken wings and buffalo shrimp.

At his theaters, no gang colors or hanging out in large groups is allowed. Before each movie, a clip of Johnson is played, reminding his audiences: “So we got a few policies that apply to everyone. They are not meant to disrespect. They’re there so we can all have a good time. So if you have a problem, leave it in the street” (Wilborn 2002).

Johnson has joined Howard Schultz, chief executive officer of Starbucks, in a franchise deal. Their partnership opened more than 100 stores. Their first location was in Ladera Center, a few miles away from the Los Angeles International Airport. The location is one of the biggest grossing in the Starbucks chain. Schultz explains that through the partnership, “we could create unique opportunities for the community—employment opportunities, opportunities for vendors—and also some hope and aspiration about a leading consumer brand doing business in underserved communities, and perhaps other companies would follow us in” (Johnson 2003:77).

Johnson’s business philosophy is simple: “All of my businesses deal with people, customer service, and entertainment because that’s what I’m good at. Everything flows together from that, and all the companies help each other” (quoted in E. Smith 1999:80).

In 2002, Johnson established a technology initiative program, currently operating in 11 states and the District of Columbia. Attempting to address the digital divide (refer to Chapter 11, “The Media”) affecting poor and minority children, the program establishes Community Empowerment Centers providing youth and community members access to computer technology, training, and experience. The centers also support the Magic of Reading Program, providing students access to books and literacy programs. As of 2014, the centers provided direct services to 255,000 students in 16 urban markets.

Community, Policy, and Social Action

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

The federal agency responsible for addressing the nation’s housing needs and improving and developing the nation’s communities is HUD. Created in 1965 as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, HUD was given the authority to enforce fair housing laws and to administer a variety of federal programs to provide a decent, safe, and sanitary living environment for every American (HUD 2003b; Martinez 2000).

HUD’s history extends back to the National Housing Act of 1934 and to the 1937 amendment that created the U.S. Housing Authority for low-rent housing. HUD’s efforts to encourage home ownership are rooted in the Housing Act of 1949, a declaration that all Americans have the right to become homeowners. Despite its expressed goal of creating “well planned and integrated residential neighborhoods,” the Housing Act did not improve housing conditions for nonminority households (Martinez 2000). The goals of the Housing Act of 1949 were reaffirmed in the Fair Housing Act of 1968, authorizing the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to make sure that home ownership was affordable and accessible for every U.S. family, including minorities and the poor (Martinez 2000). HUD continues its housing mission, expanding services to elderly residents and overseeing health care facilities and lead hazard control.

In addition, HUD has been a major player in influencing land-use decisions in urban areas (Williams 2000), spurring economic growth and development in distressed communities (HUD 2003b). HUD’s major urban initiatives have included the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1970, which established a national growth policy that emphasized new community and inner-city development; the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, which established community development block grants; and the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, which created the first enterprise zones to stimulate economic development in distressed areas. Enacted in 2000, the Community Renewal and New Markets Initiative reinforced HUD’s focus on fostering economic opportunity, enhancing the quality of life, and building a stronger sense of community in impoverished inner-city neighborhoods (Williams 2000).

With oversight provided by HUD, the renewal communities, empowerment zones, and enterprise communities program took an innovative approach to revitalization that targets inner cities and rural areas. The program brought communities together through public and private partnerships to attract the social and economic investment necessary for sustainable economic and community development (HUD 2003c). Each program integrated four principles: a strategic vision for change, community-based partnerships, economic opportunity, and sustainable community development. The program began with the assumption that local communities can best identify and develop local solutions to the problems they face (HUD 2003c). The empowerment zones and renewal communities program ended in December 2013.

Urban Revitalization Programs

The HOPE VI program was established by Congress in 1992. Originally called the Urban Revitalization Demonstration Program, from 1993 to 2006 HOPE VI spent nearly $6.2 billion to tear down public housing facilities and revitalize others into larger modern townhomes and detached homes with the goal of creating mixed-income communities in inner cities. Community and service programs are also established as part of the funding. In 2008, six housing authorities in four states (Illinois, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) were awarded a total of $97 million (HUD 2009).

The HOPE VI program was created based on recommendations from the National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing (HUD 2003a). The commission recommended revitalization in three areas: physical improvements, management improvements, and social and community services to address residents’ needs. Program grants pay for demolition of distressed public housing and rehabilitation or new construction. The program has been criticized for worsening the local housing situation because not all demolished units are replaced and program data reveal that not all residents return to the redeveloped HOPE VI sites.

Although the program’s primary focus is on the quality of housing units, HUD officials reported that the HOPE VI program has made an impact on its residents through community and supportive programs for residents. When the program was honored in 2000 by the Institute for Government Innovation, HOPE VI officials reported that nearly 3,500 public housing residents had left welfare and more than 6,500 residents had found new jobs as a result of the program (Institute for Government Innovation 2000).

The Obama administration established the Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative (NRI) in 2008, a collaborative effort with the Departments of HUD, Education, Health and Human Services, Justice, and the Treasury. The interagency strategy was promoted as an interdisciplinary, place-based, locally led and data-driven solution to the interconnected challenges of neighborhood revitalization. The initiative includes two new programs—Choice Neighborhoods and Promise Neighborhoods. Promise Neighborhoods is a neighborhood revitalization program to improve the educational and developmental outcomes of children and youth. The program utilizes place-based community change efforts, identifying and mobilizing community residents, leaders, public and private businesses and local organizations to lead and transform neighborhoods. At the end of 2012, the program was implemented in 21 states and the District of Columbia.

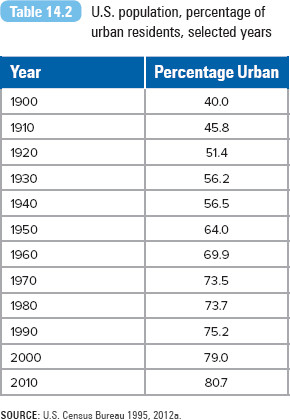

Creating Sustainable Communities

Tyler Norris (2001) chronicled the emergence and importance of the sustainable community movement. Since the early 1960s, thousands of public–private partnerships have been formed to work for economic development, educational improvement, environmental protection, health care, social issues, and other issues critical to communities. An array of private and public community groups form these partnerships. These alliances have been identified by several names and terms: healthy communities, sustainable communities, livable communities, safe communities, whole communities, and smart growth. Much of the improvement in public health, community revitalization, and quality of life can be attributed to these alliances. The best partnerships, according to Norris, bring together traditional leaders and community members often not included in the decision-making process. A summary of best practices from successful sustainable communities is presented in Table 14.7.

Examples of sustainable communities include the following:

- Highlander Research and Education Center, New Market, Tennessee. The center was established in 1932, working primarily on social change and education in the areas of labor, civil rights, and Appalachian issues. In the 2000s, the center defined its focus on four broad, interconnected issues—economic justice, racial justice, environmental justice, and democratic participation—that it believed were critical to making progress toward a more just and humane society. Current programs include an internship program, a children’s justice camp, a capacity-building/leadership program, and cultural programs. Each program serves as an invaluable resource to community groups in Appalachia and in the South.

- Greensburg GreenTown, Greensburg, Kansas. After an EF5 tornado leveled the town of Greensburg in 2007, residents, city officials, and businesses made a commitment to rebuild their city sustainably. GreenTown documents and coordinates the community’s green building projects. The program offers green tours, allowing visitors to see examples of public, single-family residential, multifamily residential, and commercial construction. GreenTown also provides technical assistance to individuals, community groups, businesses, and local governments wishing to adopt similar green building strategies.

Sociology at Work

Nonprofit Work

Mairead Shutt—Class of 2001

Undergraduate Major: Sociology

Undergraduate Minor: Business

In describing what it means to live a life of moral and civic responsibility, Anne Colby and her colleagues (2003, p. 7) say, “If today’s college graduates are to be positive forces in this world, they need not only to possess knowledge and intellectual capacities but also to see themselves as members of a community, as individuals with a responsibility to contribute to their communities.”

Because of their personal interest or commitment to similar goals, college graduates are often drawn to nonprofit organizations, organizations that are neither for-profit businesses or government agencies. Nonprofits include hospitals, private schools, churches, social welfare organizations, and charitable organizations (Taylor 2010; Butler 2009). Many of the community-based homeless programs are nonprofits. Operations are funded by grants from the government, but also from private donations.

A bachelor’s degree may be required for some entry positions; some management or administrative positions require a master’s degree in Business, Public Policy, or a related field. An often-cited downside to nonprofit work is the salary, which is typically lower than for comparable positions in the for-profit world. The type of work you can do varies widely from direct client service to recruiting volunteers to program operations or fundraising.

Mairead Shutt is a relationship manager for a medium-sized environmental education nonprofit organization. She is responsible for donor development and stewardship. “My primary goal, on a day-to-day basis, is to engage donors at a highly personal level; partner with Board Members to engage donors, and stay engaged with our education programs and the impact these programs are having on students, teachers, and the community.”

After completing her BA in Sociology and working in several nonprofits, Mairead went back to school to earn an MBA. She continues to use sociology in her work with donors. She says,

My foundation in sociology has helped me to see the people I interact with through my profession (including my colleagues, the students and teachers my organization serves, and the donors I communicate with) as unique individuals, as well as people that are impacted by a larger social system that helps inform their world views, opportunities, and preferences. This has allowed me to excel at working with diverse groups of people, keeping an open mind about people’s experience and personal history, and communicating effectively. My sociology training is also valuable to me at work because it helped me to combine both qualitative and quantitative data, research, and analysis to understand the big picture of a situation, problem, or opportunity. Today, I regularly combine hard data and metrics with more qualitative assessments to measure fundraising progress and to evaluate goals.

Mairead offers three excellent suggestions to undergraduate Sociology majors.

(1) It is acceptable to need time and space to explore and learn about the world before knowing exactly what you would like to do for the rest of your life. Don’t beat yourself up if you don’t have the answer by your senior year. (2) Take on as many learning opportunities as you can. Volunteer for causes you are passionate about and build your network. (3) Do the math. Understand the salary ranges in different sectors. While I would never discourage anyone from a career in the nonprofit world, I would encourage graduates to go in with a solid understanding of the financial realities.

Housing and Homelessness Programs

The one community response to homelessness that most of us are familiar with is the homeless shelter. These shelters have been referred to as “Band-Aid” solutions, helping but not really fixing the problem. However, these emergency programs can provide immediate and necessary assistance and, in particular, security for families with children. If these shelters are to be truly effective, more humane and supportive shelter environments should be promoted to assist families and to better prepare them for independent living (Choi and Snyder 1999). For example, existing social and human services programs will be more effective if the homeless are able to obtain the benefits that they are already eligible for (Rossi 1989), such as Social Security, disability payments, and food stamps.

In 1987, Congress passed the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act, which established assistance programs for homeless individuals and families. Under this act, 20 programs were authorized to provide emergency food and shelter, transitional and permanent housing, education, mental health care, primary health care, and veterans’ assistance services. In an effort to create more affordable housing, under Title II of the 1998 Cranston-Gonzalez National Affordable Housing Act, the HOME program provides grants to state and local governments to build, buy, or rehabilitate affordable housing for rent or homeownership. Working with community groups, the HOME program continues to serve low-income families.

Community efforts are important for the homeless and low-income families. The best-known community-based housing program is Habitat for Humanity International. Habitat serves primarily low- and very-low-income families with support from local volunteers, churches, and businesses, as well as from the sweat equity of future homeowners. Habitat families have incomes of about 30% to 50% of the area’s median income.

Project Homeless Connect began in San Francisco in 2004 when Mayor Gavin Newsom had the idea of bringing city hall staff and programs to the homeless community. The project, replicated in more than 200 U.S cities and in Canada and Australia, attempts to reach out to a city’s homeless population by delivering an array of services—social, medical, mental health, housing—all under one roof at a local venue. Quality-of-life services are also offered for the day, including haircuts, wheelchair repair, eyeglasses, and dental services. The project connects homeless men and women with program representatives and members of the community. It is staffed by more than 700 volunteers and is supported through donations from local businesses.

Although supportive services are necessary for the homeless, homelessness cannot be prevented or eliminated without enough housing for the poor. Homelessness cannot be prevented or eliminated without a livable wage, employment opportunities for inner-city residents, more efficient management of public housing projects, emergency rent assistance programs, and the expansion of low-income housing subsidies (Choi and Snyder 1999).

Project Homeless Connect

Chapter Review

- 14.1 Define demography

Demography, an essential part of urban studies, is the study of the size, composition, and distribution of human populations, as well as changes and trends in those areas. An additional demographic element is migration, the movement of individuals from one area to another.

- 14.2 Compare the processes of urbanization and suburbanization

Urbanization is the process by which a population shifts from rural to urban locales, expanded in the latter half of the 19th century. Suburbanization is the outward expansion of central cities into suburban areas, moving population centers away from city centers.

- 14.3 Explain how a population is affected by its age distribution or ethnic composition

Age distribution, or the distribution of individuals by age, is particularly important as it provides a community with some direction in its social and economic planning. Ethnic and age compositions will also affect community services and priorities.

- 14.4 Summarize how the sociological perspectives explain urbanization and its related social problems

Functionalists are critical about the shift from simple to complex societies, arguing that we lose our social bonds and connections to others in the process. The conflict perspective examines how cities are formed on the basis of racial, gender, or class inequalities stemming from capitalism. Social problems are natural to the system, arising from the unequal distribution of power among various groups. Feminist theorists have argued for the development of a comprehensive field of theory and research that acknowledges the role and experiences of women in urban environments. The structure of our urban public settings, along with how we use or experience them, contributes to how we define our cities.

- 14.5 Analyze the pros and cons of gentrification

Though gentrification involves the revitalization of an urban area, the benefits of gentrification are not evenly distributed. The quality of life and economic opportunities for lower-income or minority residents may not improve or may be negatively affected.

- 14.6 Describe the sustainable community movement

Since the early 1960s, thousands of public–private partnerships have been formed to work for economic development, educational improvement, environmental protection, health care, social issues, and other issues critical to communities. An array of private and public community groups form these partnerships.

Key Terms

- age distribution, 395

- critical political-economy perspective, 399

- crowding, 404

- domestic migration, 392

- emigration, 392

- ethnic composition, 396

- gentrification, 408

- human ecology, 392

- immigration, 392

- interior residential density, 404

- mechanical solidarity, 397

- migration, 392

- organic solidarity, 397

- overurbanization, 393

- residential segregation, 399

- socio-spatial perspective, 399

- suburbanization, 393

- urban population, 394

- urban sociology, 392

- urban sprawl, 409

- urbanization, 393

- urbanized area, 394

Study Questions

- Define urbanization and suburbanization. What are some ways that urbanization and suburbanization contribute to social problems?

- Explain the societal transition from mechanical to organic solidarity as identified by Émile Durkheim.

- From an interactionist’s perspective, how connected are you to your community? Do you define your community by what you value in it or what you use within it?

- Access to affordable and/or quality housing is a problem facing urban and suburban dwellers. Identify the extent of each problem and identify solutions for each.

- It is difficult to accurately measure the extent of the homeless problem in the United States. How does this disadvantage our understanding of homelessness? Of attempting to solve it?

- How can sociology be used to encourage the expansion of car-free or pedestrian zones? Which sociological perspective(s) would best apply?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.