Chapter 13 Crime and Criminal Justice

Learning Objectives

- 13.1 Explain the difference between biological, psychological, and sociological theories of crime

- 13.2 Identify how the different sociological perspectives examine crime

- 13.3 Summarize the different types of crime

- 13.4 Explain how race/ethnicity is an important predictor of offender or victim status

- 13.5 Describe the transformation of American policing

- 13.6 Explain whether private prisons are more effective than public prisons

Think of a crime, any crime. Picture the first “crime” that comes into your mind. What do you see? The odds are you are not imagining a mining company executive sitting at his desk, calculating the costs of proper safety precautions and deciding not to invest in them. Probably what you see with your mind’s eye is one person physically attacking another or robbing something from another via the threat of a physical attack.

—Reiman (1998:57)

When we think of crime, we imagine violent or life-threatening acts, not white-collar crimes committed by men and women using accounting ledgers and calculators as deadly weapons. Yet, an act does not have to be violent or bloody to be considered criminal. For our discussion, a crime is any behavior that violates criminal law and is punishable by fine, jail, or other negative sanctions. Crime is divided into two legal categories. Felonies are serious offenses, including murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault; these crimes are punishable by more than a year’s imprisonment or death. Misdemeanors are minor offenses, such as traffic violations, that are punishable by a fine or less than a year in jail. In this chapter, we examine crimes as a social problem. We consider a full range of crimes, not just violent events that make the headlines on your evening news. Before we review the specifics about crimes, let’s review sociological explanations of why people commit crime.

Sociological Perspectives on Crime

Biological explanations of crime tend to address how criminals are “born that way.” Early explanations were intended to classify criminal types by appearance and genetic factors, such as Cesare Lombroso’s 19th-century theory of “born criminal” types. Lombroso argued that criminals could be easily identified by distinct physical features: a huge forehead, a large jaw, and a longer arm span. Contemporary biological explanations focus on biochemical (diet and hormones) and neurophysical (brain lesions, brain dysfunctions) characteristics related to violence and criminality. Like biological theories, psychological perspectives focus on inherent criminal characteristics. Researchers link personality development, moral development, or mental disorders to criminal behaviors. Both biological and psychological theories address how crime is determined by individual characteristics or predispositions to crime, but they fail to explain why crime rates vary between urban and rural areas, different neighborhoods, or social or economic groups (Adler, Mueller, and Laufer 1991). Sociological theories attempt to address the reasons for these differences, highlighting how larger social forces contribute to crime.

Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists offer several explanations for criminal behavior. For the first explanation, we return to one of the first sociologists, Émile Durkheim. Criminal behavior, according to Durkheim, is normal and inevitable. Criminal behavior is functional because it separates acceptable from unacceptable behavior in society. Though not a criminologist, Durkheim provided the field with one of its most enduring concepts—anomie (Walsh and Ellis 2007). Recall from our discussion in Chapter 1 that Durkheim argued that society and its rules are what make people human; without any social regulation, people are able to pursue their own desires (even criminal ones). He defined anomie as a state of normlessness, a structural condition where there is no or little regulation of behavior, which leads to deviant or criminal behavior.

Robert K. Merton applied Durkheim’s theory of anomie to develop the strain theory of criminal behavior. He argued that we are socialized to attain traditional material and social goals: a good job, a nice home, or a great-looking car. We assume that society is set up in such a way that everyone has the same opportunity or resources to attain these goals. Merton explains that society isn’t that fair; some experience blocked opportunities or resources because of discrimination, social position, or talent. People feel strained when they are exposed to these goals but do not have the access or resources to achieve them. This disjunction between cultural goals and structural impediments is anomic, and this is where crime is bred (Walsh and Ellis 2007).

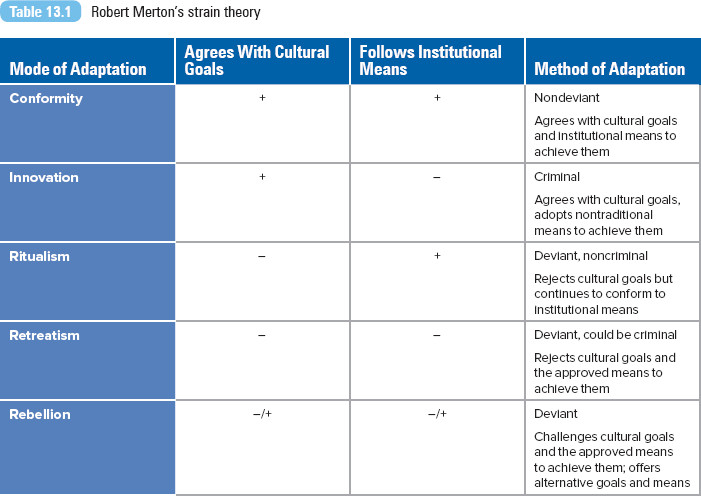

This anomie creates an opportunity to establish new norms or break the old ones to attain these goals. Merton’s strain theory explains how people adapt to life in this anomic situation. Merton presents five ways in which people adapt to society’s goals and means, as presented in Table 13.1. Most individuals fit under the first category, conformity. Conformers accept the traditional goals and have the traditional means to achieve them. Attending college is part of the traditional means to attain a job, an income, and a home. Criminal behavior comes under the innovation category. Innovators accept society’s goals, but they don’t have the legitimate means to achieve them. They are under a great strain or pressure to achieve these positively valued goals and thus innovate by stealing from their boss, cheating on their taxes, or robbing a local store to achieve them.

Working from Merton’s assumptions, scholars argue that criminal activity would decline if economic conditions improved. Solutions to crime would target strained groups, providing access to traditional methods and resources to attain goals. Several studies have confirmed that when anomie is reduced among the poor, lower crime rates may result. Factors usually associated with anomie—the prevalence of female-headed families, the percentage of the population that is African American, and family poverty rates—are more weakly related to crime in areas with higher levels of welfare support (Hannon and Defronzo 1998). But in general, there has been a lack of empirical support for Merton’s theory.

Robert Agnew (1992) expanded upon Merton’s strain theory to consider multiple individual and structural sources of strain, asserting that negative experiences and relationships motivate and promote criminal behavior (Kaufman et al. 2008). In his general strain theory, Agnew identified three types of social-psychological sources of strain: the failure to achieve positively valued outcomes (not only due to blocked opportunities as explained by Merton, but also because of individual inadequacies due to ability or skill), the removal of positive or desired stimuli from the individual (e.g., the loss of something or someone of great worth), and the confrontation with negative action (or stimuli) by others (e.g., child abuse, adverse school experiences) (Akers and Sellers 2009). Agnew’s theory is able to explain criminal offending differences by gender, class, race/ethnicity, communities, and those that occur over the life course, as well as situational variations in crime (Akers and Sellers 2009).

The second functionalist explanation links social control (or the lack of it) to criminal behavior. Whereas Merton’s and Agnew’s theories ask why someone commits a crime, social control theorists ask why someone doesn’t commit crime. Society functions best when everyone behaves. Durkheim identified how well society provides us with a set of norms and laws to regulate our behavior. According to sociologist Travis Hirschi (1969), society controls our behavior through four elements: attachments, our personal relationships with others; commitment, our acceptance of conventional goals and means; involvement, our participation in conventional activities; and beliefs, our acceptance of conventional values and norms. Delbert Elliot, Suzanne Ageton, and Rachelle Canter (1979) redefined Hirschi’s elements as integration (involvement with and emotional ties to external bonds) and commitment (expectations linked with conventional activities and beliefs). They believe that when all these elements are strong, criminal behavior is unlikely to occur.

Conflict Perspective

Sociologist Austin Turk (1969) explains that criminality is not a biological, psychological, or behavioral phenomenon; rather, it is a way to define a person’s social status according to how that person is perceived and treated by law enforcement. An act is not inherently criminal; society defines it that way. Theorists from this perspective argue that criminal laws do not exist for our own good; rather, they exist to preserve the interests and power of specific groups.

In this view, criminal justice decisions are discriminatory and designed to sanction offenders based on their minority or subordinate group membership (race, class, age, or gender) (Akers and Sellers 2009). Turk (1969, 1976) states that criminal status is defined by members of the dominant class. Criminal status is imposed on members of the subordinate class, regardless of whether a crime has actually been committed. Francis Cullen and Robert Agnew (2011, p. 271) explain,

In general, the injurious acts of the poor and powerless are defined as crime, but the injurious acts of the rich and powerful—such as the corporations selling defective products or the affluent allowing disadvantaged children to go without health care—are not brought into the reach of the criminal law.

Laws serve as a means for those in power to promote their ideas and interests against others. Law enforcement agents protect the interests and power of the dominant class at the expense of subjects. Police may use force, sometimes excessive; “when economic inequality is extreme, elites and polity as a whole may see a need for show of violent force to discourage civil disturbances” (Liska 1992:13). Excessive police force in Brazil is featured in this chapter’s “Taking a World View” section.

From this perspective, problems emerge when particular groups are disadvantaged by the criminal justice system. Although the powerful are able to resist criminal labels, the labels seem to stick to minority power groups—the poor, youth, and ethnic minorities. Minority power groups’ interests are on the margins of mainstream society, so most of their activities can be criminalized by dominant authorities (Walsh and Ellis 2007). Conflict theorists argue that the criminal justice system is intentionally unequal and serves as the vehicle for conflicts between opposing groups. The solution is the creation of a more equitable and just society (Cullen and Agnew 2011).

Feminist Perspective

For a long time, criminology ignored the experiences of women, choosing to apply theories and models of male criminality to women. Feminist researchers have been credited with making female offenders visible (Naffine 1996) and with documenting the experiences of women as the victims or survivors of violent men and as victims of the criminal justice system (Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2004). Feminist scholarship has attempted to understand how women’s criminal experiences are different from those of men and how experiences of women differ from each other based on race, ethnicity, class, age, and sexual orientation (Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2004; Flavin 2001).

Female inmates wait to be chained together before being transported for “burial duty,” where they will bury dead homeless and indigents at White Tanks Cemetery, 40 miles west of Estrella Jail in Phoenix, Arizona. Approximately 4 feet of chain separates each inmate, and there are four or five inmates to a group. Estrella Jail, in Maricopa County, is home to the only female chain gang in America.

© Scott Houston/Corbis

Freda Adler (1975) was one of the first to explain that women were “liberated” to commit crime when they were no longer restrained by traditional ideals of feminine behavior and could take on more masculine traits, including criminal behavior. Called the liberation approach, the logic of the argument is that as gender equality increases, women are more likely to commit crime. Although the approach was met with wide public acceptance, it has been discredited because of lack of empirical evidence (Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2004).

Recently, gender inequality theories have been presented as explanations of female crime. According to Darrell Steffensmeier and Emilie Allan (1996), patriarchal power relations shape gender differences in crime, pushing women into criminal behavior through role entrapment, economic marginalization, and victimization or as a survival response. The authors point out, “Nowhere is the gender ratio more skewed than in the great disparity of males as offenders and females as victims of sexual and domestic abuse” (p. 470). The logic of the inequality argument is that female crime increases as gender inequality increases.

Women are more likely to kill intimate partners, family members, or acquaintances than men are, “so the connection between women’s overall homicide offending rates and gender inequality lies largely in the connection between gender stratification and women’s domestic lives,” explains Vicki Jensen (2001:8). Jensen describes gender inequality as being composed of economic, political-legal, and social inequalities experienced by women. Lower gender equality can negatively affect women’s freedom and opportunities; these situations can push women into situations in which lethal violence seems to be the only way out. In the case of women killing abusive intimate partners, low levels of economic security limit women’s opportunities to escape abusive situations. Low levels of gender equality can increase the emphasis on traditional gender norms, placing the responsibility on women to please men and requiring that women must be submissive and accept whatever their partner does (including violence). Jensen explains that most women who kill an intimate partner do so in response to abuse situations, in imminent self-defense, or when all other strategies have failed.

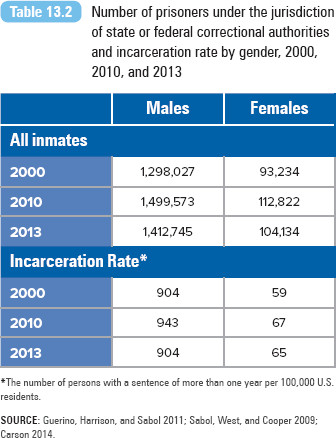

Research indicates that the surge in women’s incarceration has little to do with any major change in women’s criminal behavior. In comparison to men’s, women’s crime participation rates have remained stable over time (Becker and McCorkel 2011). Since 1995, the annual rate of growth in the number of U.S. female prisoners averaged 5%, higher than the 3% for male prisoners (refer to Table 13.2). The public’s “get tough with crime” approach, along with a legal system that encourages treating women equally to men, has resulted in the greater use of imprisonment as punishment for female criminal behavior (Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2004).

Sarah Becker and Jill McCorkel (2011) examined how gender affects access to criminal opportunities, specifically looking at the types of crime committed by men and women and considering how the presence of a male co-offender alters women’s crime participation. They found that most men and women co-offend with men; all-female offender groups are rare. Their analysis of national crime data revealed how women are more likely to be involved in gender-atypical offenses like drug trafficking, homicide, gambling, kidnapping, and weapons offenses when they have at least one male co-offender compared to when they work alone or in a same-sex group. The range of women’s crime participation increases with the presence of a male co-offender.

The number of persons with a sentence of more than one year per 100,000 U.S. residents.

SOURCE: Guerino, Harrison, and Sabol 2011; Sabol, West, and Cooper 2009; Carson 2014.

During 2013, 111,300 females were in prison, accounting for 7% of all U.S. prisoners (Glaze and Kaeble 2014). The International Centre for Prison Studies analyzed data on the number of incarcerated women worldwide at the beginning of 2012. Based on data from 212 prison systems in countries and dependent territories, the center reported that more than 625,000 women and girls were currently being held in penal institutions as pretrial detainees or having been convicted and sentenced. The highest numbers of female detainees or prisoners were in the United States (201,200), China (84,600), the Russian Federation (59,002), and Brazil (35,596) (Walmsley 2012).

The increase in the number of women inmates has caused prison officials to reconsider custody procedures for women, especially specific programs and services available to women. Also, there are major differences between male and female prisoners, which have implications for women’s confinement and release (Galbraith 2004). In particular, women are more likely (a) to be serving their first sentence, (b) to be the primary caregiver of their children, (c) to be victims of sexual abuse and trauma (Morash, Byrum, and Koons 1998), and (d) to suffer from depression. Parenting has become a focus of many programs.

Incarcerated Women

Interactionist Perspective

Interactionists examine the process that defines certain individuals and acts as criminal. The theory is called labeling theory, highlighting that what’s important isn’t the criminals or their acts, but rather the audience that labels the persons or their acts as criminal. As Kai Erickson (1964) explains, “deviance is not a property inherent in certain forms of behavior; it is a property conferred upon these forms by audiences which directly or indirectly witness them” (p. 11). The theory also considers how definitions of crime or deviance can change over time.

The basic elements of labeling theory were presented by sociologist Edwin Lemert (1967), who believed that everyone is involved in behavior that could be labeled delinquent or criminal, yet only a few are actually labeled. Lemert’s theory identifies the consequences of being labeled and treated as a criminal. He explained that deviance is a process, beginning with primary deviation, which arises from a variety of social, cultural, psychological, and physiological factors. Although most primary acts of deviance go unnoticed, they may lead to a social response in the form of an arrest, punishment, or stigmatization. Secondary deviation includes more serious deviant acts, which follow the social response to the primary deviance. Once a criminal label is attached to a person, a criminal career is set in motion.

John Braithwaite (1989) observed that nations with low crime rates are those where shaming has great social power. Braithwaite defined shaming as all processes of “expressing disapproval which have the intention or effect of invoking remorse in the person being shamed and/or condemnation by others who become aware of the shaming” (p. 9). Braithwaite agreed with Lemert that shaming could be “stigmatizing” (increasing the distance between the offender and society) and lead to additional criminal acts. However, he proposed that shaming should be “reintegrative” (restoring the link between the offender and society) and lead to less crime.

Interactionists also attempt to explain how deviant or criminal behavior is learned through association with others. Edwin Sutherland’s (1949) theory of differential association states that individuals are likely to commit deviant acts if they associate with others who are deviants. This criticism is often raised about our jail and prison systems; instead of rehabilitation, prisoners are able to learn more criminal activity and behavior while serving their sentences. Psychologists Craig Haney and Philip Zimbardo (1998) noted how “department of corrections data show that about a fourth of those initially imprisoned for nonviolent crimes are sentenced a second time for committing a violent offense. Whatever else it reflects, this pattern highlights the possibility that prison serves to transmit violent habits and values rather than to reduce them” (p. 721). Sutherland’s theory does not address how the first criminal learned criminal behavior, but he does highlight how criminal behavior emerges from interaction, association, and socialization.

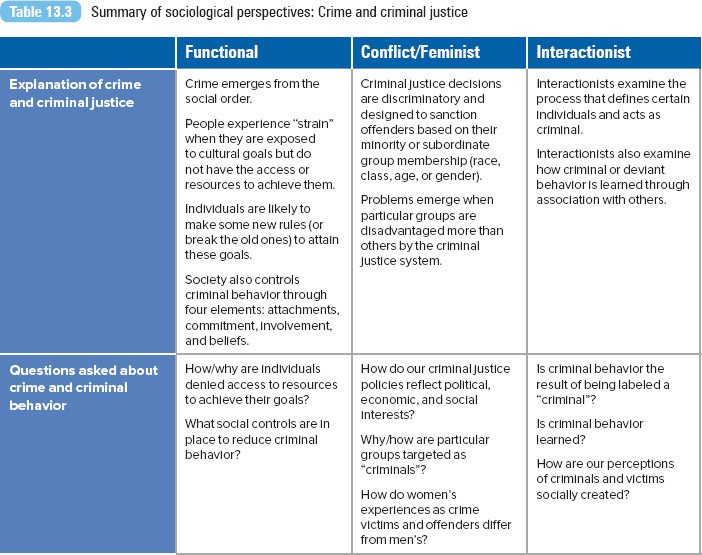

For a summary of sociological perspectives, see Table 13.3.

The Psychology of Evil

Sources of Crime Statistics

We rely on three sources of data to estimate the nature and extent of crime in the United States. The primary source is annual data collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Since 1930, the FBI has published the Uniform Crime Report (UCR), data supplied by 17,000 federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. The UCR reports two categories of crimes: index crimes and nonindex crimes. Index crimes include murder, rape, robbery, assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, arson, and larceny (theft of property worth $50 or more). All other crimes except traffic violations are categorized as nonindex crimes. The UCR provides law enforcement officers and agencies with useful data about serious rates across states, counties, and cities, as well as trend and longitudinal data since its inception. The second source of crime data emerged in 1982, when the FBI began to use the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), which adds detailed offender and victim information to the UCR data. Currently, 31 states provide NIBRS information.

However, the often-cited problem with the UCR and the NIBRS is that the data reflect only reported crimes. The FBI cannot collect information on crimes that have not been reported, but it is estimated that only 3% to 4% of crimes are actually discovered by police (Kappeler, Blumberg, and Potter 2000). Also, being reported doesn’t mean that a crime has actually occurred. The FBI does not require that a suspect has been arrested or that a crime is investigated and found to have actually occurred; it only needs to be reported (Kappeler et al. 2000).

In addition to the UCR, the FBI releases the Crime Clock, a graphic display of how often specific offenses are committed. Although it may make for good newspaper copy or give law enforcement and political officials clout (Chambliss 1988), the Crime Clock has been accused of exaggerating the amount of crime, leaving the public with the impression that they are in imminent danger of being victims of violence (Kappeler et al. 2000).

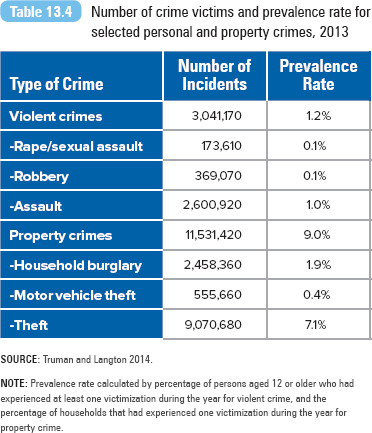

The third data source about crime is the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS or NCS), which has been published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics since 1972. The survey is based on victimization surveys first conducted in Denmark (in 1720) and Norway (in the late 1940s). Twice a year, the U.S. Census Bureau interviews members of about 77,200 households regarding their experience with crime. The NCVS identifies crime victims whether or not the crime was reported. The survey includes information about victims and crimes but covers only six offenses (compared with the eight index crimes reported by the UCR). Also included is information on the experiences of victims with the criminal justice system, self-protective measures used by victims, and possible substance abuse by offenders. NCVS crime victim data for 2013 are presented in Table 13.4.

SOURCE: Truman and Langton 2014.

NOTE: Prevalence rate calculated by percentage of persons aged 12 or older who had experienced at least one victimization during the year for violent crime, and the percentage of households that had experienced one victimization during the year for property crime.

The results of the NCVS are often compared with the UCR to indicate that the number of crimes committed is actually higher than the number of crimes reported, suggesting that the UCR may not be an adequate measure of violent crime. However, “a more thoughtful interpretation of the inconsistency between these statistical reports concludes that while neither the UCR nor the NCVS is by itself an adequate measure of violence, each is an estimate of the scope and nature of violent crime” (Brownstein 2001:8–9).

Types of Crime

Violent Crime

Violent crime is defined as actions that involve force or the threat of force against others and includes aggravated assault, murder, rape, and robbery. The victimization rate for crimes of violence in 2013 was 23.2 victimizations per 1,000 people age 12 or older, declining from 26.1 in 2012 (Truman and Langton 2014).

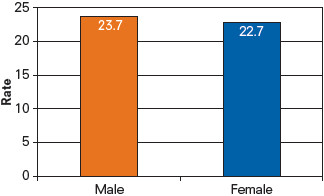

In 2013, males and females had similar rates of violent victimization—23.7 per 1,000 males and 22.7 per 1,000 females (Truman and Langton 2014). Male homicide victimization rates are higher than female rates worldwide. Comparing homicide victimization rates from 1950 to 2001, the countries with the highest male homicide victimization rates were Mexico, 35.13 per 100,000, followed by Puerto Rico, 24.64. For female homicide, the highest victimization rate was in Puerto Rico, 3.53 per 100,000; Mexico was second at 3.40. For the same period, rates for the United States were reported at 11.88 for males and 3.37 for females (LaFree and Hunnicutt 2006). For 2010, the victimization rate for U.S. males (11.6 per 100,000) was three times higher than the rate for females (3.4 per 100,000) (Cooper and Smith 2011).

Males are more likely to be victimized by a stranger, whereas women are more likely to be violently victimized by a friend, an acquaintance, or an intimate partner (U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics 2003a). For rape and sexual assault victimization tracked for 1994–2010, most victims (about 75%) knew their offender. For 2005–2010, 34% of all rape or sexual assault victimizations were committed by an intimate partner (former or current spouse, girlfriend or boyfriend), 6% by a relative or family member, and 38% by a friend or acquaintance (Planty et al. 2013). In 2012, the federal government expanded the definition of forcible rape to include male victims and the types of sexual assault that would be counted by the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report. The revised definition includes forcible oral or anal penetration, along with nonconsensual sex (Savage 2012).

Intimate violence (violence at the hands of someone known to the victim) is primarily committed against women in both the developed and developing worlds. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2005), in its study of women from 10 different countries, revealed that violence by an intimate partner is “common, widespread, and far-reaching in its impact” (WHO 2005:viii). WHO reports that the proportion of ever-partnered women who had experienced physical or sexual violence or both by an intimate partner ranged from 29% to 62% in most studied countries. Women in Japan were the least likely to experience either type of violence, and the greatest amount of violence was reported by women living in provincial rural areas of Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Peru, and the United Republic of Tanzania (WHO 2005). In 2010, U.S. women experienced 407,700 rape, sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault victimizations at the hands of an intimate partner; among men, 101,530 were victims of violent crimes by an intimate partner (Truman 2011).

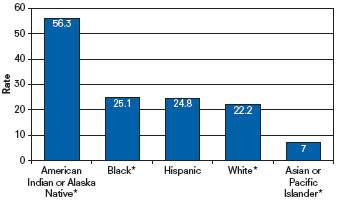

Since 1973, Blacks have had the highest violent crime victimization rates. In 2013, 25.1 of 1,000 Black people experienced a violent crime versus 22.2 out of 1,000 Whites and 24.8 out of 1,000 Hispanics (Truman and Langton 2014). Research by William Julius Wilson (1996) and Robert Sampson and Wilson (1995) revealed that structural disadvantages, rather than race, contribute to higher levels of crime and victimization in Black communities (Ackerman 1998). The structural factors include neighborhood poverty, unemployment, social isolation, and economic disadvantage.

Data collected for 2008 reveal that disabled persons are more likely to experience higher rates of violence (40 crimes per 1,000 persons age 12 or older) than those without a disability (2% or 20 crimes per 1,000 persons). The violent crime rate was approximately 86% for youth ages 16 to 19 with disabilities versus 34% for youth without. Females with a disability had a higher victimization rate than males with a disability (Harrell and Rand 2010). Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for a summary of violent crime victimization by selected social characteristics.

Exploring social problems

Violent Crime Victimization

Figure 13.1 Victimization rate per 1,000 persons aged 12 or older, by gender, 2013

SOURCE: Adapted from Truman and Langton 2014.

Figure 13.2 Victimization rate per 1,000 persons aged 12 or older, by race/ethnicity, 2013

SOURCE: Adapted from Truman and Langton 2014.

NOTE: *Excludes persons of Hispanic Origin

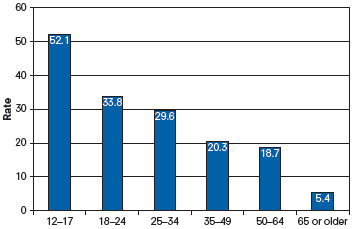

Figure 13.3 Victimization rate per 1,000 persons aged 12 or older, by age, 2013

SOURCE: Adapted from Truman and Langton 2014.

What Do You Think?

Figure 13.1 to 13.3 present the rate of victimization for violent crimes per 1,000 persons age 12 or older by gender, race/ethnicity, and age. The discussion in the previous section reviews data trends presented in these figures.

From a sociological perspective, explain why some groups are more likely to be victims of violent crime than others. For example, what makes the 12- to 17-year-old age group more than twice as likely to experience violent crime than the group of 35- to 49-year-olds?

Property Crime

Property crime consists of taking money or property from another without force or the threat of force against the victims. Burglary, larceny, theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson are examples of property crimes. Property crimes make up about three fourths of all crime in the United States. In 2013, there were an estimated 16.8 million property crimes, including 3.3 million household burglaries and 661,250 motor vehicle thefts (Truman and Langton 2014).

Juvenile Delinquency

The term juvenile delinquent often refers to a youth who is in trouble with the law. Technically, a juvenile status offender is a juvenile who has violated a law that applies only to minors 7 to 17 years old, such as cutting school or buying and consuming alcohol (Sanders 1981). In certain cases, minors can be tried as adults. Crimes committed by juveniles are more likely to be cleared by law enforcement than crimes committed by adults.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention monitors data on rates of juvenile crime. For 2011, the total number of juvenile arrests was 1.47 million. Females accounted for 29% of juvenile arrests. Almost half of all juvenile arrests involved larceny-theft, simple assault, drug abuse violations, disorderly conduct, or liquor law violations. Only 5% of all violent crimes involved offenders younger than age 18 (Puzzanchera 2013). Unlike the United States, many countries do not collect systematic data on delinquency, and among the countries that do, their data are described as “incomplete because of faulty record keeping” (Stafford 2004:486).

For 2011, the racial composition of the U.S. juvenile population was 76% White (Hispanics are also classified as White), 17% Black, 5% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 2% American Indian. Although Black youth accounted for 17% of the youth population between the ages of 10 and 17, they were involved in 51% of the arrests for violent crimes and 35% of property crimes (Puzzanchera 2013).

Delinquency is often explained by the absence of strong bonds to society or the lack of social controls. In studies of serious adolescent crime, research indicates that the economic isolation of inner-city neighborhoods, along with the concentration of poverty and unemployment, leads to an erosion of the formal and informal controls that inhibit delinquent behavior (Laub 1983). Juveniles without any or much social control are likely to engage in illegal behavior when they live in any environment that offers opportunities for illegal activities. Youth who are strongly bonded to conventional role models and institutions (parents, teachers, school, community leaders, and law-abiding peers) are least likely to engage in delinquent behaviors.

Inside Juvenile Prison

White-Collar Crime

The term white-collar crime was first used by Sutherland in 1949. He used the term to refer to “a crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation” (Sutherland 1949:9). Since then, the term has come to include three categories of offense: crimes committed by an offender (someone of high social status and respectability as described by Sutherland), crimes committed for financial or economic gain, and crimes taking place in a particular organization or business (Barnett n.d.).

The FBI (1989) has defined white-collar crime by the type of crime:

[White-collar crime includes] illegal acts which are characterized by deceit, concealment, or violation of trust and which are not dependent upon the application or threat of physical force or violence. Individuals or organizations commit these acts to obtain money, property or services; to avoid payment or loss of money or services; or to secure personal and business advantage. (p. 3)

Such acts include credit card fraud, insurance fraud, mail fraud, tax evasion, money laundering, embezzlement, and theft of trade secrets. Corporate crime may also include illegal acts committed by corporate employees on behalf of the corporation and with its support. Corporate fraud has been identified as the highest priority of the FBI’s Financial Crimes Section. As of the end of fiscal year 2011, the FBI had pursued 726 cases, several which involved losses to public investors that individually exceeded $1 billion (FBI 2011). White-collar crimes cost taxpayers more than all other types of crime.

One of the most widespread forms of white-collar crime is Internet fraud and abuse, also known as cybercrime. The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) is a joint partnership between the FBI and National White Collar Crime Center. IC3 handles complaints and crimes that include identity theft, online credit card fraud schemes, theft of trade secrets, sales of counterfeit software, and computer intrusions (a hacker breaking into a system). Years ago, when computer systems were relatively self-contained, there was no concern about cybercrime. Committing cybercrime is easier with the growth of the Internet, increasing computer connectivity, and the availability of break-in programs and information. As computer-controlled infrastructure and networks have expanded, many systems—power grids, airports, rail systems, hospitals—have become vulnerable (Wolf 2000). In response to Internet crimes, the FBI and the Department of Justice have established computer crime teams or offices. Some states, such as Massachusetts and New York, have created high-technology crime units.

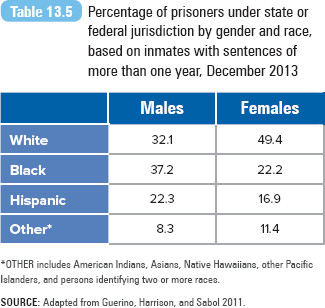

Other includes American Indians, Asians, Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, and persons identifying two or more races.

SOURCE: Adapted from Guerino, Harrison, and Sabol 2011.

Cybercrime Infographic

The Inequalities of Crime—Offenders and Victims

Offenders

Reports consistently reveal that African American males are overrepresented in incarceration statistics. Most jail or prison inmates are male and African American (refer to Table 13.5). On December 31, 2013, almost 3% of the Black male U.S. population of all ages were imprisoned, compared to 1% of Hispanic males and 0.5% of White males. On the same day, Black females were imprisoned at more than twice the rate of White females (Carson 2014). That a category of people is overrepresented among violent offenders does not necessarily mean that this group is responsible for more violent acts (Brownstein 2001). Keep in mind that these statistics are based only on those who were caught by the criminal justice system.

A number of studies confirm that regardless of the seriousness of the crime, racial and ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans and Hispanics, are more likely to be arrested or incarcerated than are their White counterparts. Though Latinos make up only 13% of the U.S. adult population, they account for 40% of federal prison inmates, due in part to tougher enforcement of immigration laws (Lopez and Light 2009). This is also true for minority juvenile delinquents. Minority youth are overrepresented at every stage in the juvenile justice system; they are arrested more often, detained more often, overrepresented in referrals to juvenile court, and institutionalized at a disproportionate rate compared with White youth (Joseph 2000). In its analysis of contacts between police and the public for 2008, the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that Black (12.3%) and Hispanic (5.8%) motorists were more likely to be searched during a traffic stop than White drivers (3.9%) (Eith and Durose 2011). Blacks and Hispanics were more likely than Whites to report being involved in an incident where police force was used (Eith and Durose 2011).

An early criminological explanation was offered by Marvin Wolfgang and Franco Ferracuti (1967), who argued that Blacks have adopted violent subcultural values, creating a “subculture of violence.” Although this is an often-cited theory, there is insufficient empirical evidence to support the idea that Blacks are more likely to embrace a violent value system. Actually, studies have indicated that White males are more likely to express violent beliefs or attitudes than Black males (Cao, Adams, and Jensen 2000).

Family structure, specifically the presence of female-headed households in African American communities, has also been identified as a potential source for racial crime disparities. Yet, criminological research has not articulated how family structure or family processes are related to crime (Morenoff 2005). Does the structure of the family itself increase the likelihood of crime? Is the incidence of crime related to the amount of parental supervision, the level of parental effectiveness, or the nature of the parent–child relationship? These questions remain the focus of researchers.

Criminologists and sociologists have examined patterns of racial bias or discrimination in the law enforcement and criminal justice system. Racial profiling is the use of race or ethnicity by law enforcement, consciously or unconsciously, as a basis of judgment for criminal suspicion. Racial profiling is supported by some in law enforcement as a rational and efficient strategy, targeting those most likely to commit crime. Yet most agree that profiling is dysfunctional, creating “racial inequities by denying people of color privacy, identity, place, security, and control over their daily life” (Cross 2001:5). President Obama, responding to the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, said, “Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago... There are very few African-American men in this country who have not had the experience of being followed when they are shopping at a department store. That includes me” (White House 2013).

Michelle Alexander (2010) characterizes mass incarceration as a caste system, much like the Jim Crow laws (1876–1965) that defined permanent second-class status for Black Americans. Specifically, the War on Drugs served as a form of legalized discrimination, entrapping African Americans in the criminal justice system. The harm to individuals and families only intensifies when prisoners are released. She explains,

They enter a separate society, a world hidden from public view, governed by a set of oppressive and discriminatory rules and laws that do not apply to everyone else. They become members of an undercaste—an enormous population of predominately black and brown people who, because of the drug war, are denied basic rights and privileges of American citizenship and are permanently relegated to an inferior status. (Alexander 2010:181–82)

New racial profiling rules were released by the Obama administration after nationwide protests over the decisions in New York and Ferguson, Missouri, not to prosecute White officers for the deaths of unarmed Black men (Apuzzo and Schmidt 2014). Citing the need for “even-handed law enforcement,” the categories of racial profiling were expanded to include religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Under the new rules, law enforcement officials cannot consider any of those factors in making routine or spontaneous law enforcement decisions. Agencies whose officers make traffic stops may not use any of these categories as a reason to pull someone over. The new guidelines apply to federal law enforcement officers and to local police assigned to federal task forces, but not to local police agencies (Apuzzo and Schmidt 2014; U.S. Department of Justice 2014).

Mass Incarceration: Locked out of the American Dream

Victims

Early studies on crime victims tended to perpetuate the image that the victim was simply at the “wrong place at the wrong time” (Davis, Taylor, and Titus 1997). Following that reasoning, not being a victim of crime could be explained simply as good luck. However, research indicates that some individuals, by virtue of their social group or social behavior, are more prone than others to become victims (Davis et al. 1997). What people do, where they go, and with whom they associate affect their likelihood of victimization (Laub 1997).

For most individuals, their interaction with police officers is limited to traffic violation stops. Police departments are incorporating new methods of policing based on community and problem-solving approaches, hoping to increase the interaction between officers and citizens.

© Douglas Kirkland/Corbis

Victimization is distributed across key demographic dimensions (Laub 1997). Victimization rates are substantially higher for the poor, the young, males, Blacks, single people, renters, and central city residents (Davis et al. 1997). The likelihood of being injured because of a violent crime is higher among the young, the poor, urban dwellers, Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians (Simon, Mercy, and Perkins 2001). Injury rates are lower for the elderly, for people with a higher income or higher educational attainment, and for people who are married or widowed (Simon et al. 2001).

Black males have the highest rate of violent victimization, and White females have the lowest (Laub 1997). Blacks also have the highest rate of overall household victimization. Although rates of violent crimes declined during the 1990s, mortality from homicide among minority groups is still high. Homicide is the leading cause of death among Black males between the ages of 15 and 24, and it is the second leading cause of death for Latino males in the same age group (Rich and Ro 2002). People who have been victims once are at an elevated risk of becoming victims again. Repeat victimization is likely to occur in poor, predominantly Black areas (Davis et al. 1997).

Our Current Response to Crime

The Police

For 2011, there were more than a million full-time law enforcement employees. About 70% were sworn officers. Local police departments were the largest employer (60% of all employees) (FBI 2014a). We rely on the police force to serve as the first line of defense against crime, and some officers lose their lives in the line of duty. In 2013, 27 law enforcement officers were feloniously killed in the line of duty, and 49 were killed in accidents (FBI 2014b).

American policing has gone through substantial changes during the past several decades (MacDonald 2002). Traditional models of policing emphasized high visibility and the use of force and arrests as deterrents to crime. Policing under these models relies on three tactics: police patrols, rapid response to service calls, and retrospective investigations (M. Moore 1999). These models reinforce an “us” versus “them” division, sometimes pitting the police against the public they were sworn to protect. High-profile incidents of police brutality and violence, such as the cases that involved Rodney King in Los Angeles and Amadou Diallo in New York City, increased public distrust and tainted the image of policing.

Studies indicate that “net of all other factors, race and personal experience with racial profiling are among the strongest and most consistent predictors of attitudes toward the police” (Weitzer and Tuch 2002:445). Whites trust police more and have more positive interactions with them than do Blacks; Hispanics fall between these two groups (Norris et al. 1992). Black youth tend to have the most negative or hostile feelings toward police (Norris et al. 1992). Residents from poor or disadvantaged areas have a much lower regard for the police than does the general public. However, research has also indicated that when citizens believe they are treated fairly, they tend to grant police more legitimacy and are more likely to comply with police (Stoutland 2001).

Police departments are now incorporating new methods of policing based on the community and problem-solving approaches (Goldstein 1990; MacDonald 2002). The community policing approach refers to efforts to increase the interaction between officers and citizens, including the use of foot patrols, community substations, and neighborhood watches (Beckett and Sasson 2000). By 2000, two thirds of all local police departments and 62% of sheriff’s offices had full-time sworn personnel engaged in community policing activities (U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics 2003b). We learn more about community policing in the section titled “Community, Policy, and Social Action.”

Prisons

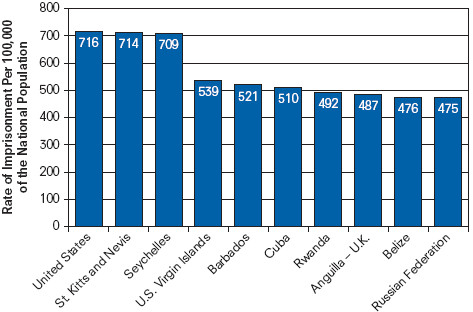

Despite the decline in crime rates, prison populations are increasing (Anderson 2003), though the rate of new admissions has declined in recent years (Sabol, West, and Cooper 2009). At the end of 2013, the federal and state inmate population was more than 1.6 million. Though the United States represents 5% of the world’s population, the number of incarcerated in our country represents nearly 25% of the world’s prison population (Rosen 2010). Data reveal that the United States has the highest prison population rate in the world (refer to Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4 Highest prison population rates in the world, 2013

SOURCE: Adapted from Walmsley 2014.

Mandatory sentencing, especially for nonviolent drug offenders, is a key reason why inmate populations have increased for the past 30 years. Drug offenders now make up more than half of all federal prisoners (Anderson 2003). The United States incarcerates more people for drug offenses than any other country (Justice Policy Institute 2008). The majority of men and women sentenced under these laws are nonviolent, low-level drug offenders—couriers, street dealers, bystanders, or drug addicts—convicted for possession or sales of small amounts of drugs (Human Rights Watch 1999, 2000).

Additionally, probation and parole revocations are a growing source of prison admissions. Among prisoners released in 2005 who returned to prison, 49.7% had a parole or probation violation or an arrest for a new offense within three years that led to imprisonment, and 55.1% had a parole or probation violation or an arrest that led to imprisonment within five years (Durose, Cooper, and Snyder 2014).

Along with the increase in the number of prisoners comes an increase in prison budgets. In 2010, the average state inmate cost about $31,286 per year (Henrichson and Delaney 2012). Average operating costs per inmate varied by state, indicating differences in costs of living, wage rates, and other related factors. The three states with the highest annual operating costs per inmate were New York ($60,076), New Jersey ($54,865), and Connecticut ($50,262).

Human Rights Watch (2012) documented the aging of the U.S. prison population, reporting that the number of prisoners age 65 or older increased by 63% between 2007 and 2010. For 2012, there were 26,200 prisoners in this age group. Providing medical care to older prison populations suffering from chronic, disabling, and terminal illnesses will be expensive, no different from the level of care and spending required for an older nonprison population. While no systematic data are available regarding the annual cost of care, Human Rights Watch (2012) reported a range of state expenses from $4,000 to $8,500 per elderly prisoner per year.

What is the purpose of the prison system? Some argue that the system is intended to rehabilitate offenders, to prevent them from committing crime again. However, beginning in the mid-1970s, U.S. rehabilitation programs and community-based programs began to lose funding. Probation and parole offices redefined their core missions from treatment to control and surveillance (Tonry 2004). Other Western governments, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian countries, continue to make large investments in treatment and educational programs in comparison with the United States (Albrecht 2001), with evidence revealing that some programs are able to reduce future reoffending (Gaes et al. 1999). For example, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden have established crime prevention agencies that develop programs for developmental, community, and situational crime prevention (Tonry and Farrington 1995); there are no comparable agencies in the United States (Tonry 2004).

The U.S. record of recidivism (or repeat offenses) indicates how badly our prison system is working. Data analyzed by the Pew Center on the States (2011) found that the three-year return-to-prison rate for inmates released in 1999 was slightly higher than the recidivism rate for inmates released in 2004, 45.4% versus 43.3%. Released offenders returned to prison for committing a new crime or for a technical violation (not reporting to their parole officer or failing a drug test). Previous studies indicate that men, Blacks, non-Hispanics, and prisoners with longer prior records were more likely to be rearrested. Younger prisoners were also more likely to reoffend than were older prisoners (Langan and Levin 2002). The Bureau of Justice Statistics released data for 2007, noting that 15.5% of 1.2 million parolees returned to incarceration that year (Glaze and Bonczar 2009).

Taking a World View

Policing in Brazil

Policing in Brazil has a dark and ugly history. The death squads of Brazil began in 1958, when Army General Amaury Kruel, chief of the police forces in Rio de Janeiro, handpicked a group of special policemen to combat rising theft and robberies in the city. These “bandit hunters” were given permission to hunt and kill these criminals. In other states and cities, teams of police hunters were formed to pursue pistoleiros (armed criminals), undesirables, and gangsters. Each new death squad, whether targeting economic or political criminals, became more distant from the formal criminal justice system (Huggins 1997). Through several political regimes, Brazilian police have never abandoned their practices of violent enforcement and vigilantism.

After 21 years of military dictatorship (1964–1985), the civilian government (inaugurated in 1985) set out to reform Brazil’s authoritarian practices. In 1988, armed with a new constitution, the democratic leadership lifted the barriers to political participation and attempted to restore the legal premises of universal citizenship rights (Mitchell and Wood 1999). In 1996, President Fernando Henrique Cardoso released the National Human Rights Plan, a comprehensive set of measures to address human rights violations in Brazil, including cases of police abuses (Human Rights Watch 1997).

Yet, police violence and human rights violations all increased dramatically under democratic rule (Caldeira and Holston 1999). Police are some of the primary agents of violence in Brazil. According to organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, many citizens continue to suffer systematic abuse and violations at the hands of their own police force. Police in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo have killed more than 11,000 people since 2003 (Human Rights Watch 2009). For 2012, 1,890 people died during police operations in Brazil, an average of five people per day (Human Rights Watch 2014).

Although Brazilian law endorses due process, criminal proceedings and police methods subvert this principle (Mitchell and Wood 1999), supporting extralegal conduct in the majority of cases (Huggins 1997; Mitchell and Wood 1999). Government leaders also offer their support of extralegal activities. Three days after state civil police officers killed 13 suspected drug traffickers, Marcello Alencar, governor of Rio de Janeiro, was quoted as saying, “These violent criminals have become animals. They are animals. They can’t be understood any other way. These people don’t have to be treated in a civilized way. They have to be treated like animals” (Human Rights Watch 1997).

According to Martha Huggins (1997), police violence in Brazil comes in two forms: on-duty police violence and death squads. Highly organized, elite police units carry out extralegal killings while on duty. The police violence is usually deliberately planned and conducted during routine street sweeps and dragnets, actions justified by the state’s war on drugs and crime. There is also death squad violence conducted by a group of murderers, usually off-duty police, who are paid by local businesses or politicians for their services. Huggins calls them privatized security guards serving commercial or political interests.

In 1985, Brazil implemented women’s police stations, Delegacias de Policia dos Direitos da Mulher (DPMs or delegacias). The DPMs were created in response to pressure from feminist groups demanding that violence against women be addressed. The first groups were formed in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, where the first DPM was established in 1985 (Hautzinger 1997). The female officers at each station are conventionally trained police, with no specialized training or qualifications for serving at the DPM except for the fact that they are women. There are more than 250 DPMs in Brazil today (Hautzinger 2002). Although domestic violence complaints were the original mission of the DPMs, these account for only 80% of the caseloads (Hautzinger 2002). Human Rights Watch (1995) reports that despite the presence of DPMs, “many rural and urban women have found police to be unresponsive to their claims and have encountered open hostility when they attempted to report domestic violence.”

The Death Penalty

Seven states executed 35 inmates in 2014. For the year, there were 3,035 inmates serving death sentences. The majority of death row inmates were White (43%), followed by Blacks (42%) and Hispanics (13%). Since 1976, a total of 1,394 prisoners have been executed (Death Penalty Information Center 2014).

The death penalty was instituted as a deterrent to serious crime. The penalty applies only to capital murder cases, where aggravating circumstances are present. However, research indicates that capital punishment has no deterrent effect on committing murder. In fact, states with the death penalty have murder rates significantly higher than states without the death penalty. Kappeler and his colleagues (2000) explained that only a small proportion of people charged with murder can be sentenced to death. For example, between 1980 and 1989, 206,710 murders were reported to the police, but during the same period, only 117 executions were carried out. This is about 1 execution for every 1,767 murders committed during the same period (Kappeler et al. 2000).

Worldwide, 139 countries have abolished the use of the death penalty. In 2013, 778 were executed around the world in at least 22 countries. Eighty percent of these executions were in three countries: Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The number of executions in China, believed to be in the thousands, cannot be confirmed (Amnesty International 2014).

Opponents of the death penalty point out the racial disparities in its application. The most significant studies of racial disparities point to the race of the victims as the critical factor in sentencing. Those convicted of committing a crime against a White person are more often sentenced to death. Data reported by the Death Penalty Information Center (2012) reveal that the majority of victims in death penalty cases were White (76%), followed by Blacks (15%). Nationally, only 50% of murder victims are White. In their analysis of 1990–1999 California death penalty cases, Michael Radalet and Glenn Pierce (2005) reported that those who killed a non-Hispanic African American were 56% less likely to be sentenced to death than were those who killed non-Hispanic Whites. The difference increases to 67% when comparing those sentenced to death for killing Whites versus those sentenced for killing Hispanics.

Lessons From Death Row Inmates

Community, Policy, and Social Action

U.S. Department of Justice

We may perceive our criminal justice system as a single system when, actually, we have 51 different criminal justice systems: 1 federal and 50 state systems. The federal system is led by the U.S. Department of Justice. Headed by the Attorney General of the United States, the Department of Justice comprises many separate component organizations, including the FBI; the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which controls the border and provides services to lawful immigrants; the Antitrust Division, which promotes and protects the competitive process in business and industry; and the Bureau of Prisons, which oversees correctional operations and programs (U.S. Department of Justice 2002).

Funding for the U.S. Department of Justice and its organizations comes from federal legislation. The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act was the largest crime bill in history, providing funds for 100,000 new officers, $9.7 billion for prisons, and $6.1 billion for prevention programs. Under the Violence Against Women Act, the Office on Violence Against Women, administered by the Department of Justice, has awarded more than $6 billion in grant funds to U.S. states and territories. These grants have helped state, tribal, and local governments and community-based agencies to train personnel, establish domestic violence and sexual assault units, assist victims of violence, and hold perpetrators accountable (Office on Violence Against Women 2010).

Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Programs

The U.S. Department of Justice also supports the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. As its mission, the office attempts to provide national leadership, coordination, and resources to prevent and respond to juvenile delinquency and victimization. The office is guided by the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974 reauthorized by Congress in 2002 (U.S. Congress, 2002).

The office sponsors more than 15 programs targeting juveniles and their communities. The Tribal Youth Program is part of the Indian Country Law Enforcement Initiative to support tribal efforts to prevent and control juvenile delinquency. The Child Protection Division administers programs related to crimes against children, such as the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and the Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force. Recently the office has been promoting and studying the positive influence of mentoring on at-risk and delinquent youth. It sponsors a 32-site demonstration program to develop and test program models that incorporate advocacy and teaching roles for mentors.

Faith-based and community organizations have also been involved in delinquency prevention programs. One such program is the Blue Nile rites-of-passage program based in Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church (established before President George W. Bush’s initiative). Since 1994, the program has relied on a community-based mentoring component to address the spiritual, cultural, and moral character development of African American youth (Harlem Live 1999). In general, the program was designed to have “a positive impact on the family relationships, self-esteem, sexual behaviors, drug use, peer and sibling relationships, and the religious and social values of the youth” (Irwin 2002:30). Darrell Irwin (2002) says that faith-based initiatives contain much of what has been found to be valuable in traditional mentoring programs, with the church as a backdrop. In the Harlem program, students are assigned to a mentor, either a church minister or a congregation member. During weekly meetings, mentors work with their partnered youth, emphasizing problem-solving and decision-making skills. In addition, the mentors introduce the youth to different educational and cultural activities as examples of potential community interactions. The program also includes a media literacy component where students learn how to film, edit, direct, and produce their own videos (Harlem Live 1999).

The New American Prison

In an effort to reduce the costs of incarceration to state and federal correctional agencies, the idea of private correctional institutions has gained momentum. The perception that public prisons were deteriorating and overcrowded helped to encourage the growth of private prisons in the 1980s (Pratt and Maahs 1999). Private prisons incarcerate about 7% of the sentenced adult population, usually housing low-risk offenders. Globally, Australia has the highest proportion (17%) of prisoners in private prisons, followed by the United Kingdom (10%) (L. Roth 2004).

It has been argued that private correctional institutions save taxpayers money, providing more services with fewer resources; studies reveal a slight advantage to private prisons and demonstrate a reduction in per-inmate cost over time (Larason Schneider 1999). State correction officials are also responding to the problem of chronic prison overcrowding. For example, one third of Hawaii’s 6,000 state inmates are jailed in private prisons in Arizona, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Oklahoma because Hawaii does not have enough room in its own state facility (S. Moore 2007). Studies have indicated that the savings from private prisons are likely to come from lower wages and benefits, fewer staff, more efficient uses of staff, or a combination of these factors (Camp and Gaes 2002).

Scott Camp and Gerald Gaes (2002) found that private prisons did not perform better than public ones and in some cases did worse. According to the researchers, one of the most reliable indicators of prison operations is the rate at which inmates test positive for use of drugs or alcohol. If substance abuse is high, it indicates a pattern of poor security practices. For the private institutions, tests showed no drug use in 34% of the facilities and low to high drug use in 66% of the facilities. Nearly 62% of public prisons showed no evidence of drug use. In their analysis of another important performance measure, William Bales et al. (2005) found no significant difference in recidivism rates between public and private prisoner offenders. There were no significant differences among three groups in their study: adult males, adult females, and youth offender males.

Passed in 1996, the Prison Litigation Reform Act requires prisoners to exhaust all internal and administrative remedies before they can file federal lawsuits to challenge the conditions of their confinement or to report civil rights violations. The act was intended to prevent frivolous or unfounded lawsuits, but it has made it impossible for prisoners with valid complaints to be heard. Prisoners cannot file lawsuits for mental or emotional injury unless they can also show that physical injury occurred. Prisoners are required to pay for their own court filing fees; monthly installments can be taken out of their prison commissary account (American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU] 1999). The act also prohibits prison officials from settling lawsuits by agreeing to make changes in unconstitutional prison conditions. The ACLU and its National Prison Project have challenged the constitutionality of the Prison Litigation Reform Act, claiming that it “slams the courthouse door on society’s most vulnerable members” (ACLU 1999). Despite its questionable constitutionality, many government leaders and courts have applauded the act.

Private Prisons

Community Approaches to Law

Community Oriented Policing Services, or COPS, was created in response to the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The goal of the program is to shift from traditional law enforcement to community-oriented policing services, a change that includes putting law enforcement officers within a community and emphasizing crime prevention rather than law enforcement (COPS 2003). As stated on the COPS website, “Community policing is a law enforcement philosophy that focuses on community partnerships, problem-solving and organizational transformation” (COPS 2014). Researchers found that “police administrators have hailed community oriented policing as the preferred strategy for the delivery of services” (Novak, Alarid, and Lucas 2003:57).

One of the central premises of community policing is the relationships among the police, citizens, and other agencies. Since 1981, the National Night Out program has worked to strengthen police–community partnerships in anticrime efforts. Usually scheduled in August, National Night Out activities first involved just turning on the front porch lights of houses, but they now include block parties, cookouts, parades, and neighborhood walks involving community members and police officers (National Night Out 2003). The community plays an important role in ensuring its own safety. In community policing, “problem solving requires that police and the community work together in identifying neighborhood problems, and that the community assumes greater ‘guardianship’ of the neighborhood” (Greene and Pelfrey 1997:395).

COPS sponsors grants and initiatives in selected communities, offering specialized training and programs to police professionals, such as technological innovations (mobile computing, computer-aided dispatch, automated fingerprint identification systems) or policing methods. In addition, the program supports innovative strategies linking police with their communities. COPS highlighted the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department’s El Protector Program as one of the best strategies for working with communities whose members have limited English proficiencies. The program, established in 2004, includes two full-time officers who speak fluent Spanish. Assigned to precinct areas with the highest Latino populations, the officers work with community members and business leaders to reduce DUIs, traffic fatalities, and domestic violence.

It is difficult to assess the effectiveness of community policing methods because many of these community approaches have not been sufficiently implemented (MacDonald 2002). Jihong Zhao, Matthew Scheider, and Quint Thurman (2002) report that an additional problem is that much of the research designed to assess COPS programs is limited to the individual programs or cities. However, based on their analysis of COPS programs in 6,100 cities, the researchers discovered that COPS hiring and innovative programs resulted in significant reductions in local violent and nonviolent crime rates in cities with populations greater than 10,000. In addition, an increase of $1 in grant funding per resident for hiring contributed to a decline of 5.26 violent crimes and 21.63 property crimes per 100,000 residents. However, COPS grants had no significant impact on violent and property crime rates in cities with fewer than 10,000 residents. Data also indicate how the COPS program accelerated the establishment of new community policing programs and tactics, such as late-night recreation programs, victim assistance programs, and efficiencies in police work in funded cities (Roth and Ryan 2000).

In Focus

A Public Health Approach to Gun Control

The most deadly U.S. shooting occurred on April 16, 2007, when Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University student Cho Seung-Hui shot and killed 32 people, including himself. In 2005, a Virginia court had declared Cho mentally ill and a danger to himself and sent him for psychiatric treatment. A month before the shooting, he purchased two semiautomatic pistols and 50 rounds of ammunition. Under federal law, Cho should have been prohibited from purchasing a gun after the Virginia court declaration. Federal law prohibits anyone who has been “adjudicated as a mental defective,” as well as those who have been involuntarily committed to a mental health facility, from purchasing a gun.

Since the shooting at Virginia Tech, there have been several other deadly incidents. In July 2011, confessed killer Anders Behring Breivik killed 77 in Norway in two attacks, a bombing in downtown Oslo and a shooting massacre at a youth camp. A year later, James Holmes opened fire in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, during a premiere of The Dark Knight Rises. Holmes killed 12 and injured 56 others. Holmes amassed his weapons over several months, purchasing much of his ammunition via the Internet. In December 2012, gunman Adam Lanza killed 26 people, 20 of them children between the ages of 5 and 10 years, at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. The guns used by Lanza were legally registered to his mother Nancy, also one of his victims. Each tragedy reignited the debate over the regulated sale of firearms in the United States.

According to David Hemenway (2004),

The 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting reignited the debate over gun control. Many parents of the Sandy Hook victims lent their support to national and state campaigns to prohibit the sale and manufacturing of certain types of semi-automatic guns and magazines with more than 10 rounds of ammunition.

Gordon M. Grant / Splash News/Newscom

The United States has more firearms in civilian hands than any other high income nation. About 25 percent of adults in the United States personally own a firearm. Many gun owners have more than one firearm; some 10 percent of adults own over 75 percent of all firearms in the country. The percentage of households with a firearm has declined in the past two decades; about one in three households now contains a firearm. (p. 85)

He notes that public health approaches have reduced the burden of infectious disease, tobacco-related illness, and motor vehicle injuries, suggesting that a similar approach could be successfully applied to reducing gun violence, focusing on the impact of gun violence on one’s community, and encouraging collaboration, research, and comprehensive policies. Hemenway (2004) explains what would be necessary for a public health approach to gun control:

Like the approach to reducing motor vehicle injuries, a public health approach to curtailing problems caused by firearms suggests pursuing a wide variety of policies while maintaining the ability of law-abiding Americans to use guns responsibly. This approach emphasizes the importance of obtaining accurate, detailed and comparable information each year on the extent and nature of the problem. For each motor vehicle death in the United States, the Fatality Analysis Reporting System collects data on more than one hundred variables. This information suggests interventions and permits evaluation of which policies are effective and which are not.

A major problem is that the detailed national information about firearm injuries does not exist. For example, whether most unintentional firearm injuries occur at home or away from home, or with long guns or handguns, is unknown. Many groups have backed the creation of a national violent death reporting system to provide detailed information on all homicides, suicides, and unintentional firearm deaths.

Although firearms are among the most lethal consumer products, killing tens of thousands of civilians each year, firearm manufacturing is one of the least-regulated industries in the United States. No federal regulatory body has specific authority over firearm manufacturing, which is exempt from regulation by the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

A public health approach would create incentives for firearm manufacturers to make products that reduce rather than increase the burden on law enforcement. Rather than producing and promoting firearms that appear primarily designed for criminal use, such as those who do not retain fingerprints, manufacturers could produce guns with unique, tamper resistant serial numbers. They could also make guns that “fingerprint” each bullet to permit authorities to match bullet and firearm with a high degree of accuracy.

Policies common in other developed countries—registration of handguns, licensing of owners, and background checks for all gun transfers—could reduce the U.S. homicide rate substantially by making it harder for adolescents and criminals to obtain handguns.

The public health approach to reducing gun violence emphasizes the need for prevention as well as punishment, recognizes that alternations in the product and the environment are more likely to be effective than attempts to change individual behavior, and urges the pursuit of multiple strategies to tackle the problem. The public health community understands the importance of involving the entire community and sees roles for many groups, including educational institutions, religious organizations, medical associations and the media.

SOURCE: Hemenway 2004.

Voices in the Community

Max Kenner

The brainchild of Max Kenner, the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) was created in 1999 to address the educational needs of prisoners and to provide them with the opportunity and the means to attain higher education while remaining within the correctional system.

To understand the logic behind such a program as BPI, one must revisit the 1970s, a time when the federal government looked favorably upon college in prison programs. Since then, numerous studies have shown that college in prison programs reduce the rate of recidivism, lower the number of violent incidents that occur within prisons, reestablish broken relationships between incarcerated parents and their children, and create a general sense of hope among inmates. Despite these beneficial consequences, in 1994, President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act into law, essentially abrogating federal support and funding for existing programs. As a result, of the 350 programs that had arisen, only three remained.

“The prison system is so large,” Kenner muses, “because it locks people up at a young age, and when they return home, they are less equipped to work, to attend school, and to function as social beings.” These deficiencies result in an increased chance that released prisoners will commit another crime of a greater magnitude, thereby paving the road back to prison, but this time for a much longer sentence.

Most state correctional systems offer some sort of educational programming. However, only a third offer college courses or degrees.

AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli

As an undergraduate of Bard College, Kenner immersed himself in the prevailing culture of social justice advocacy on campus. In 1999, he and a group of like-minded individuals made the unsettling discovery that of the 72,000 men and women in the New York State prison system, four out of every five inmates were from New York City. Armed with this finding, and an increasing frustration with governmental divestment from education in social services, the group set out to tackle the issue of educating prison inmates. “We felt that if we were really going to commit ourselves to some kind of effort to improve social justice it should be broad-based, and it should be based on public institutions,” explains Kenner.

With that in mind, Kenner embarked on a mission to make Bard College an institutional home that would allow either faculty or students to gain access to prisons by lending its transcript services and by offering credit-bearing courses and degrees to prison inmates.

After the national collapse of the college in prison programs, however, there was an incredible distrust among people in corrections who wanted to see the colleges come back and people in higher education who wanted colleges in the prison. According to Kenner, colleges only wanted to offer courses if they could make a profit or if they could do so under ideal circumstances. Some colleges were simply not interested.

It took Kenner one and a half years to begin working with prisons. He was able to organize student volunteer programs that allowed students to conduct writing, GED, literacy, and theology workshops within the prison. “By the spring of my senior year, we had some 40 students volunteering at the prison on a weekly basis. Many of them said that it was the single most profound and influential thing that they had done at their time at Bard,” says Kenner.

Upon graduation, Kenner made a proposal to Bard College President Leon Botstein, requesting that the college provide him with an office and grant him access to its transcripts so that they could begin offering college credit to prison inmates. The only stipulation was that Kenner would have to find a way to raise money to support the program.

Following graduation, Kenner was given a salaried position by Episcopal Social Services (EPS). “The Bard Prison Initiative officially started as a partnership between EPS and Bard College,” says Kenner, “and five months later, in 2001, we began offering credit bearing courses to 17 students.”

Currently, BPI offers two educational programs to inmates. Anyone with a GED can apply for the pre-college program and those with a higher level of education can apply for the associate’s degree program. In the fall [of 2005], BPI will begin offering a bachelor’s program that is consistent with the degree conferred to Bard College students. Those who have successfully completed the associate’s degree program in two or three years can then reapply for admission into the bachelor’s degree program.

Kenner hopes that the programs that have been implemented thus far will remain active and prove to be self-sustaining. He remains a passionate advocate for the return of college in prison programs and will continue to play an integral role in enhancing their opportunities.

BPI currently enrolls 300 incarcerated men and women in five prisons across New York state. The curriculum offerings include more than 60 courses each semester. By 2013, 300 degrees had been awarded to BPI graduates. Through the Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison, Bard College is providing support to college-in-prison programs in other states and schools (Bard Prison Initiative 2014).