Chapter 12 Alcohol and Drug Abuse

Learning Objectives

- 12.1 Explain how the different sociological perspectives explain alcohol and drug problems

- 12.2 Describe how the social structure regulates drinking

- 12.3 Identify the correlates of Ecstasy use among college students

- 12.4 Assess the theory that college students mature out of heavy or binge drinking

- 12.5 Examine the pros and cons of the drug legalization movement

President Richard Nixon first declared the War on Drugs in 1971. Some refer to it as a war with “no rules, no boundaries, no end” (PBS 2000). Since the mid-1980s, the United States has adopted a series of aggressive law enforcement strategies and criminal justice policies aimed at reducing and punishing drug abuse (Fellner 2000). Changes in federal law require all sentenced federal offenders to serve at least 87% of their court-imposed sentences. Many drug offenders are subject to mandatory minimum sentences based on the type and quantity of drugs involved in their arrest (Scalia 2001). According to the most recent Uniform Crime Report (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2013), 1,552,432 drug arrests were made in 2012. Although some consider the large number of drug arrests a good sign, critics charge that mandatory sentencing denies drug users what they really need: access to treatment. Tougher sentencing has failed to decrease the availability of drugs and has failed to reduce illicit drug use. And some say that the war’s greatest legacy is the increase in the prison population; since 1980, the number of drug offenders in federal prison has increased by 21 times (Washington Post 2014).

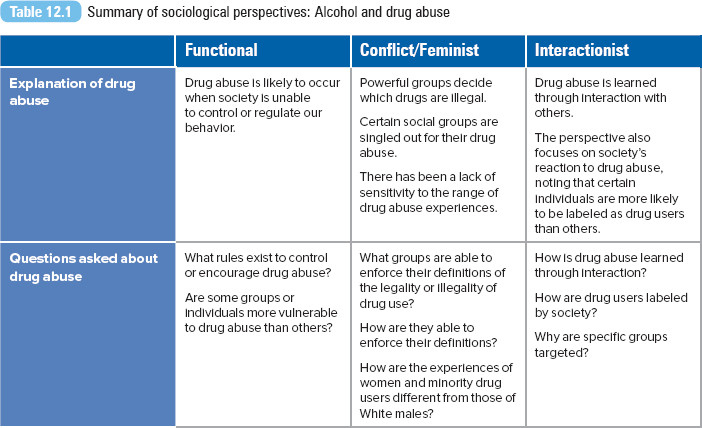

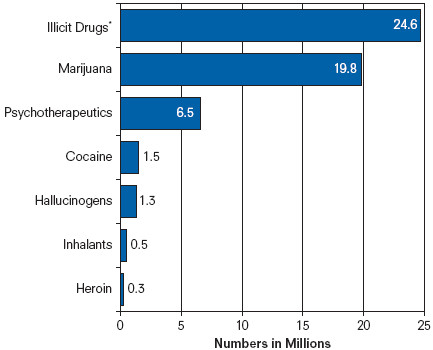

There seems to be no argument about the seriousness of the drug problem in the United States and worldwide. According to the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 24.6 million Americans (or 9.4%) age 12 or older reportedly were current users of illicit drugs other than marijuana (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] 2014). (Refer to Figure 12.1 for illicit drug use among persons aged 12 years or older.) Nearly 17 million American adults abuse alcohol or are alcoholics (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA] 2014). Globally, more than 76 million individuals have diagnosable drinking problems (World Health Organization 2004), and between 15 and 39 million are problem drug users (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC] 2012b). The most widely produced and consumed illicit drug is cannabis, or marijuana. Refer to Figure 12.2 for more information.

Figure 12.1 Past-month illicit drug use among persons aged 12 or older, by drug, 2013

SOURCE: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014.

NOTE: Includes marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or prescription-type psychotherapeutics.

Although we might focus first on one drug user and his or her personal trouble with drugs, it doesn’t take long to recognize how drug use affects the user’s family and friends, workplace or school, and neighbors and community. Throughout this chapter, we will examine the social problem of drug abuse, reviewing its extent, its social consequences, and our solutions. We begin first with a look at how the sociological perspectives address the problem of drug abuse.

Sociological Perspectives on Drug Abuse

Biological and psychological theories attempt to explain how drug abuse is based on the individual. Both perspectives assume that there is little a person can do to escape from his or her abuse: a person’s abuse is genetic or inherited. Abuse may emerge from a biological or chemical predisposition or from a personality or behavioral disorder. Such explanations also have consequences for treatment. Programs focus on the individual, arguing that the abuser needs to be “fixed.” Although both perspectives have been important in shaping our understanding of drug abuse, these perspectives cannot explain the social or structural determinants of drug abuse. In this next section, we will examine how sociological perspectives address the problems of drug abuse.

Figure 12.2 Annual prevalence of cannabis use as a percentage of the population aged 15–64, selected countries, estimates from 2007 to 2009

SOURCE: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2012b.

Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists argue that society provides us with norms or guidelines on drug use. Cross-cultural studies reveal that there is variation in the way people expect to behave when they drink. For example, violent behavior is associated with alcohol consumption in the United States, Great Britain, and Australia; yet drinking behavior is described as “peaceful and harmonious” in Mediterranean and South African countries (Social Issues Research Center 1998).

A set of social norms identifies the appropriate use of drugs and alcohol. The use of prescription drugs, as directed by a physician, is considered acceptable behavior. Prescription drugs alleviate pain, reduce fevers, and curb infections. Alcohol in moderation may be routinely consumed with meals, for celebration, or for health benefits. One glass of red wine a day has been shown to reduce one’s risk of heart disease.

Yet society also provides norms regarding the excessive use of drugs. For example, college students share the perception that excessive college drinking is a cultural norm (Butler 1993); this perception is enforced by the media and advertisers (Lederman et al. 2003). Aaron Brower (2002) argues that binge drinking is determined by and is a product of the college environment. For example, because of particular organization norms that support binge drinking, members of Greek social organizations have higher rates of binge drinking when compared to other college students (Chauvin 2012). According to Brower (2002), unlike alcoholics, college students are able to turn their willingness to binge drink on and off depending on their circumstances (e.g., whether they have to study for an exam).

To explain drug abuse, functionalists identify a culture or the social structure as the cause. In examining substance abuse among adolescents, researchers contend that peers may be the most influential (Allen et al. 2003). Howard Kaplan, Steven Martin, and Cynthia Robbins (1984) write, “The use of illicit drugs persists as part of ongoing peer subculture(s) which may endorse, if not require, use of illicit drugs” (p. 271). Peer influence may be direct or indirect: peers provide social opportunities to engage in substance abuse, and peers shape attitudes toward substance abuse (Leventhal and Cleary 1980; Prinstein and Wang 2005).

Émile Durkheim believed that under conditions of rapid cultural change, there would be an absence of common social norms and controls, a state he called anomie. If people lack norms to control their behavior, they are likely to pursue self-destructive behaviors such as alcohol abuse (Caetano, Clark, and Tam 1998). During periods when individuals are socially isolated (such as moving to a new neighborhood, experiencing a divorce, or starting a new school year), they may experience high levels of stress or anxiety, which may lead to deviant behaviors, including drug abuse. Society can also be the source of role strain—when an individual has insufficient resources to deal with demanding social situations or circumstances. The strain occurs when the demands of one’s role exceed one’s ability and resources to fulfill that role (Wheaton 1990). Illicit drug use or self-medication can be perceived as an adaptive coping response to stress—people turn to drug use to reduce their level of stress (Crutchfield and Gove 1984). For example, Shelly McGrath, Catherine Marcum, and Heith Copes (2012) documented how drug use was used as a coping strategy among adult prisoners experiencing a sense of danger or stress during their incarceration.

Conflict Perspective

Although many drugs can be abused, conflict theorists argue that intentional decisions have been made over which drugs are illegal and which ones are not. Powerful political and business interest groups are able to manipulate our images of drugs and their users.

Economist Arthur Benavie (2009) explains how the War on Drugs in this country is defined by subjective social, religious, and political positions. For example, drugs are classified by five schedules, categories that define their susceptibility to abuse and medical application. Criminal penalties are applied to the drugs in Schedules I and II, dangerous drugs with a high potential for abuse. Benavie highlights how the classification of these drugs is determined by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) rather than the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the Surgeon General.

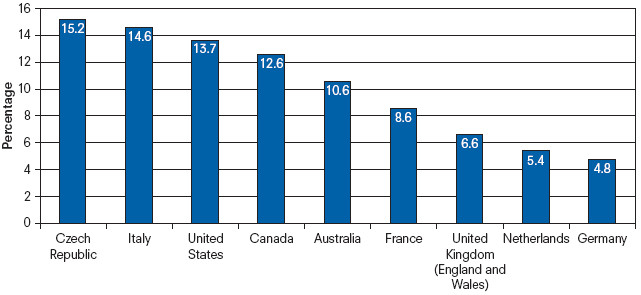

During the late 1800s and early 1900s cocaine was promoted as a medicinal ingredient to treat pain or coughing. Heroin and opium were also used in over the counter treatments.

Encyclopædia Dramatica

Our history of drug laws, concludes Benavie (2009), has little to do with objective information about the effects or dangers of illicit drugs. Drug policy has been fueled by racial, ethnic, and economic antagonisms. For example, heroin, opium, and marijuana were considered legal substances in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but public opinion and law changed when their use was linked to ethnic minorities and crime. Opium smoking, most associated with Chinese immigrants brought here to work on the railroads, became the subject of intense antidrug efforts after completion of the railroad system. At the same time, the oral consumption of opium, more widespread among Whites, was never considered problematic (Reinarman and Levine 1997).

According to Benavie (2009), the War on Drugs is a crusade, fueled by a fear of social disorder and disease, a perceived threat to our capitalistic economic structure, and a religious crusade against sin and vice.

Why Fight Drugs?

Feminist Perspective

Theorists and practitioners in the field of alcohol and drug abuse have ignored the experiences unique to women, ethnic groups, gay and lesbian populations, and other marginalized groups. Women face unique social stigmatization as a result of their drug use and may also experience discrimination as they attempt to receive treatment (Drug Policy Alliance 2003).

The scientific literature did not address women’s addiction until the 1970s. Specifically, there has been a lack of sensitivity to the range of drug abuse experiences beyond the male or White perspective. Early prevention and treatment models treated female abusers no differently than men were treated, failing to provide comprehensive services for women such as prenatal and gynecologic care, contraceptive counseling, job training, and abuse counseling (Roberts 1991). However, there is increasing recognition of the importance of gender-specific and gender-sensitive treatment models, including the development of separate women’s treatment programs. Female users have a variety of different treatment and psychosocial needs, influenced by their backgrounds, experiences, and drug problems. Most outpatient clinics do not provide child care, and many residential programs do not admit children (Roberts 1991). And single, career-oriented women without children will have different treatment needs and priorities than will single mothers or married mothers (National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information [NCADI] 2003a).

Data suggest that the dramatic increase in women’s imprisonment (refer to Chapter 13) is due primarily to the prosecution of drug offenses, leading some researchers to characterize the War on Drugs as the war on women (Bush-Baskette 1998). Katherine Beckett (1995) and Dorothy Roberts (1991) describe how women of color were unfairly targeted in the War on Drugs in the 1980s. As crack cocaine use spread throughout the inner cities, prosecutors shifted their attention to drug use among pregnant women, making drug and alcohol abuse during pregnancy a crime. The approach treated pregnant drug users as criminals and was “aimed at punishing rather than empowering women who use drugs during their pregnancy” (Beckett 1995:589). As Beckett (1995) explains, “Prosecutions of women for prenatal conduct thus create a gender specific system of punishment and obscure the fact that male behavior, socio-economic conditions, and environmental pollutants may also affect fetal health” (p. 588). Roberts (1991) argues that poor Black women are the primary targets for prosecutors. Research indicates that African American women are about 10 times more likely than are other women to be reported to civil authorities for drug use.

In the 1990s, federal drug legislation shifted to methamphetamine offenses, making some of the penalties similar to crack cocaine offenses. Though methamphetamine convictions were last among the five types of drugs women were convicted for in 1996 (10.3%), Stephanie Bush-Baskette and Vivian Smith (2012) report that by 2006, the number of methamphetamine convictions had doubled (23%). There was a 300% increase in the number of women convicted and sentenced for methamphetamine offenses between 1996 and 2006. White women represented the largest percentages of women incarcerated for methamphetamine. The majority of those women had little or no prior criminal record.

Interactionist Perspective

Sociologists Edwin Sutherland and Howard Becker argue that deviant behavior, such as drug abuse, is learned through others. Sutherland (1939) proposed the theory of differential association to explain how we learn specific behaviors and norms from the groups we have contact with. Deviance, explained Sutherland, is learned from people who engage in deviant behavior. In his classic study “Becoming a Marijuana User,” Becker (1963) demonstrated how a novice user is introduced to smoking marijuana by more experienced users. Learning is the key in his study:

No one becomes a user without (1) learning to smoke the drug in a way which will produce real effects; (2) learning to recognize the effects and connect them with drug use . . . ; and (3) learning to enjoy the sensations he perceives. (Becker 1963:58)

This perspective also addresses how individuals or groups are labeled abusers and how society responds to them. For example, consider alcohol abuse among the Native American population. Alcohol abuse and alcoholism are leading causes of mortality among Native Americans, and there are disproportionately higher rates of alcohol-related crimes among Native Americans. Yet Malcolm Holmes and Judith Antell (2001) argue that alcohol abuse and its related problems are not entirely objective phenomena; they also involve interpretation and stigmatization of deviant behavior. One persistent societal myth maintains that as a group, Native Americans have problems handling alcohol. However, research indicates that factors such as demography (a young population) and geography (rural Western environment) may explain high rates of alcohol-related problems in Native American populations.

The authors highlight the considerable variation in drinking patterns within and between tribal communities; there is a large segment of the Native population that do not drink or are non-problem drinkers (Hawkins and La Marr 2012). The social construction of the “drunken Indian” stereotype links alcohol abuse to the perceived “weaker” cultural and individual characteristics of Native Americans. Holmes and Antell (2001) explain, “The persistence of such myths in the symbolic-moral universe of the dominant White culture, despite evidence to the contrary, suggests that alcohol use by Native Americans still documents allegations of weak will and moral degeneracy” (p. 154).

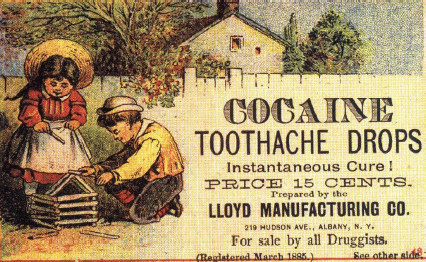

For a summary of these four sociological perspectives, see Table 12.1.

What Is Drug Abuse?

Drug abuse is the use of any drug or medication for a reason other than the one it was intended to serve or in a manner or in quantities other than directed, which can lead to clinically significant impairment or distress. Drug addiction refers to physical or psychological dependence on the drug or medication. Although many drugs can be abused, three drugs will be reviewed in the following section—alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana—along with rave or club drugs. Marijuana and club drugs are considered illicit (illegal) drugs. Most of the information presented in this section is based on data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP). For more information, log on to the SAGE edge select companion site, Chapter 12, at http://edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e.

Alcohol

Alcohol is the most abused drug in the United States. Although the consumption of alcohol by itself is not a social problem, the continuous and excessive use of alcohol can become problematic. Four symptoms are associated with alcohol dependence or alcoholism: craving (a strong need to drink), loss of control (not being able to stop drinking once drinking begins), physical dependence (experiencing withdrawal symptoms), and tolerance (the need to drink greater amounts of alcohol to get “high”) (NIAAA 2003b). Alcohol use is related to a wide range of adverse health and social consequences, both acute (traffic deaths or other injuries) and chronic (stroke, alcohol dependence, liver damage) (NIAAA 2005).

National surveys reveal the differences in alcohol consumption by individual attributes, cultural factors, and structural factors. For example, in 2013, current drinking (12 or more drinks in the past year) among adults was highest for Whites and persons reporting two or more races. Heavy alcohol use (five drinks on a single day at least once a month for adults) was highest among Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders and Whites. Overall, alcohol consumption was lowest among Asian, Hispanic, and Black adults and Asian and Black college students (SAMHSA 2014).

Studies suggest that ethnic/racial groups have different sets of norms and values regulating drinking. While some groups exhibit low rates of problem drinking because their culture associates the use of alcohol primarily with eating, social occasions, or rituals (Herd and Grube 1996), other ethnic/racial groups may consider drinking as an activity separate from eating or ritual celebrations, leading to higher rates of problem drinking. In an examination between first- and second-generation Asian American adults, second-generation adults are at higher risk for alcohol use or abuse. Some researchers attribute this higher risk to the process of acculturation—when individuals from different cultures come together, practices and behaviors that are different from one’s own group may be adopted or learned. Due to acculturation, second-generation Asian Americans begin to develop drinking behaviors similar to their non-Asian peers (Iwamoto, Takamatsu, and Castellanos 2012).

Although social class, occupational and social roles, and family history of alcohol use all play a role in determining the drinking patterns of people in general, specific factors put women particularly at risk (Collins and McNair 2003). Research indicates that a woman’s risk for drinking increases with the experience of negative affective states, such as depression (Hesselbrock and Hesselbrock 1997) or loneliness, and negative life events, such as physical or sexual abuse during childhood or adulthood (Wilsnack et al. 1997). Other factors decrease women’s chances of developing alcohol problems. Traditionally, women are socialized to abstain from alcohol use or to drink less than men (Filmore et al. 1997). Women who do not participate in the labor force may have less access to alcohol than men do (Wilsnack and Wilsnack 1992), and women’s roles as wife and mother may also discourage alcohol intake (Leonard and Rothbard 1999).

World Health Organization: Alcohol Abuse

Tobacco and Nicotine

Tobacco is the world’s number-one problem drug, killing more people than all other drugs combined (Goode 2004). According to the World Health Organization (2014), if current smoking patterns continued, by 2030 8 million people per year worldwide would die of diseases caused by cigarette smoking. Cigarette smoking is the most prevalent form of nicotine addiction, and tobacco is the most frequently used addictive drug in the United States (NCADI 2003b). Nicotine is both a stimulant and a sedative to the central nervous system. An average cigarette contains about 10 milligrams of nicotine. Through inhaling the cigarette smoke, the smoker takes in 1 to 2 milligrams of nicotine per cigarette. In 2013, 66.9 million Americans (or 26%) reported current use of a tobacco product (SAMHSA 2014).

In the United States, the prevalence of smoking is highest among Native Americans and Alaska Natives (40.1%), followed by persons who reported two or more races (31.2%), Whites (29.5%), Blacks (27.3%), and Hispanics (21.9%) (SAMHSA 2014). Thirty-seven percent of young adults aged 18 to 25 years were current smokers (SAMHSA 2014).

Cigarette smoking is the most important preventable cause of cancer in the United States. It has been linked to most cases of lung cancer in Europe and in the United States (Crispo et al. 2004). Smoking has also been linked to other lung diseases, such as chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and to cancers of the mouth, stomach, kidney, bladder, cervix, pancreas, and larynx. The overall death rates from cancer are twice as high among smokers as nonsmokers (NIDA 1998). It is estimated that more than 400,000 annual deaths are attributable to cigarette smoking in the United States (American Lung Association 2006).

Passive or secondhand smoke is a major source of indoor air contaminants. Nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke at home or work increase their risk of developing heart disease by 25% to 30% and lung cancer by 20% to 30% (NIDA 2006). Secondhand smoke is estimated to cause about 3,000 lung cancer deaths per year and may contribute to as many as 34,000 deaths related to cardiovascular disease in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2014a; NIDA 1998). More than 79,000 adults die each year as a result of passive smoking in the European Union countries (European Lung Association 2006).

Despite the persistent public health message that smoking is bad for your health, smoking among teenagers has been on the rise since 1991 (Lewinsohn et al. 2000). In a study comparing adolescent smokers with nonsmokers, adolescent smokers were found to have more stressful environments, more academic problems, and poorer coping skills than nonsmokers have. Adolescent smoking has also been associated with a number of environmental factors, such as disruptive home environment, parental and peer smoking, low social support from family and friends, conflict with parents, and stressful life events (Lewinsohn et al. 2000). About three out of four teen smokers will become adult smokers (CDC 2014b).

E-cigarettes arrived on the U.S. market in 2007. The cigarettes are battery operated, turning nicotine and other chemicals into a vapor. Smoking the cigarettes is also referred to as vaping. As of November 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had not reviewed clinical studies about the safety of e-cigarettes. The FDA had not approved any e-cigarette product for therapeutic uses or as a cessation aid. Concerns have been raised about the appeal of the e-cigarettes to the teen market. In 2014, the National Institute on Drug Abuse report found that e-cigarette use surpassed traditional cigarette use among 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade teens (Tavernise 2014). According to the CDC (2014b), more than 260,000 youth who had never smoked a cigarette used an e-cigarette in 2013, representing a three-fold increase from 79,000 teen e-cigarette users in 2011.

Marijuana

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug, widely used by adolescents and young adults (NIDA 2002). An estimated 125 and 203 million (between 2.8% and 4.5%) of the world population used cannabis at least once during the past year (UNODC 2012a). It is a favorite drug among youth and adolescents, with use (at least once in a lifetime) estimated as high as 37% in some countries (UNODC 2006). The major active chemical in marijuana is THC or delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, which causes the mind-altering effects of the drug. THC is also the main active ingredient in oral medications used to treat nausea in chemotherapy patients and to stimulate appetite in AIDS patients (ONDCP 2006).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 38.4% of surveyed high school students and 49% of college students reported lifetime use of marijuana. Longitudinal data show increases in marijuana use during the 1960s and 1970s, declines in the 1980s, and increasing use since the 1990s (NIDA 2002). In 2010, there were a reported 19.8 million current (past-month) users of the drug, or 7.5% of the population (SAMHSA 2014).

Acute marijuana use can impair short-term memory, judgment, and other cognitive functions, as well as a person’s coordination and balance, and it can increase heart rate. Chronic abuse of the drug can lead to addiction, as well as increased risk of chronic cough, bronchitis, or emphysema. Addictive use of the drug may interfere with family, school, or work activities. Smoking marijuana increases the risk of lung cancer and cancer in other parts of the respiratory tract more than smoking tobacco does (NIDA 2002). Marijuana smoke contains 50% to 70% more carcinogenic hydrocarbons than tobacco smoke does (ONDCP 2006). Because marijuana users inhale more deeply and hold their breath longer than cigarette smokers do, they are exposed to more carcinogenic smoke than cigarette smokers are.

Club or Rave Drugs

Raves began in the 1990s as illegal underground all-night dance parties. Though raves are advertised as safe and/or alcohol-free parties, they remain a popular venue for the distribution of club drugs such as MDMA (an amphetamine-based hallucinogenic), GHB (a nervous system depressant), methamphetamine (a central nervous stimulant), ketamine (a hallucinogenic), and Rohypnol (a sedative, also referred to as the date rape drug). Today, rave parties are larger organized festivals featuring different types of electronic dance music. Drugs remain a key part of the rave experience.

Antidrug organizations have heightened their concern regarding the risks and health consequences associated with MDMA use. Ecstasy is the pill form of the drug, while Molly is the powder or crystal form of MDMA. Even when they are not fatal, Ecstasy or Molly are not harmless. MDMA produces an intense release of serotonin in a user’s brain, which can cause irreparable damage to the brain and memory functions. Research indicates that long-term brain damage, especially to the parts of the brain critical to thought and memory, may result from its use. Users may also experience psychological difficulties (such as confusion, depression, and sleeping problems) while using the drug and sometimes for weeks after. As a result of using the drug, individuals can also experience increases in heart rate and blood pressure and physical symptoms such as nausea, blurred vision, or faintness (NIDA 2003a). When users overdose, they can experience rapid heartbeat, high blood pressure, faintness, panic attacks, and even loss of consciousness (Vaughn 2002).

Though advertised as drug free zones, raves continue to be a venue for the distribution and use of club drugs like MDMA and GHB.

© milos-kreckovic/iStock

In a study of undergraduates at a large midwestern university, Carol Boyd, Sean E. McCabe, and Hannah d’Arcy (2003) found that men and women were equally likely to have used Ecstasy, and that several factors predicted its use. White students were more likely to report lifetime Ecstasy use than were African American or Asian students. According to the researchers, sexual orientation was also related to Ecstasy use: those who identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual were more likely to report lifetime, annual, or past-month Ecstasy use than were heterosexual students. Students with a grade point average (GPA) of 3.5 or higher were consistently less likely to have used Ecstasy in the past year or their lifetime than were students with GPAs below 2.5. Students who reported binge drinking within the past two weeks were also more likely to report past-month Ecstasy use. In a separate study, Kira Levy et al. (2005) confirmed the role of social pressure in the experimentation with and use of Ecstasy among college students. When sober and surrounded by Ecstasy-using friends, students described the urge to experience the drug’s effect with others.

Though deaths associated with the drug remain rare, overdoses and emergency room visits have increased in recent years. In 2013, two rave concertgoers died from Molly overdoses. Ecstasy-related emergency room visits increased from 10,200 in 2004 to 17,865 visits in 2008, an increase of 75% (ONDCP 2014). Canada is the primary source of MDMA smuggled into the United States.

Electronic Music and Ecstasy

Colorado Drug Legislation

The Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado: The Impact

Taking a World View

The Marijuana Legalization Movement

The 2012 legalization of marijuana in Colorado and Washington has been credited with encouraging legalization efforts in other states and in other countries. The small South American country of Uruguay was the first in the world to legally regulate the production, sale, and consumption of marijuana for adults. Beginning in 2014, Uruguayans over the age of 18 have had legal access to marijuana through home cultivation of up to 6 plants per household, membership clubs where 15 to 45 members can collectively grow up to 99 plants, or sales of up to 10 grams per week through licensed pharmacies. The system is regulated through the Institute for Regulation and Control of Cannabis (IRCCA) and includes educational and health programming for residents (Hetzer 2014).

As reported by the United Nations Office of Drug and Crime (2014), between 125 million and 227 million people (or between 2.7% and 4.9%) between the ages of 15 to 64 years were estimated to have used marijuana in 2012. Globally, countries with the highest rate of use are Western and Central Europe and North America.

Marijuana is grown in almost every country in the world, ranging from personal home cultivation to large-scale farm and warehouse operations. In 2012, more than 5 tons of cannabis were seized. The largest quantity was seized in the United States, which accounts for over 60% of the seizures worldwide. The area with the second highest amount of seizers was Central and South America and the Caribbean (UNODC 2014).

In its 2014 report, the UNODC expresses concern regarding cannabis legalization in Washington and Colorado. The organization warns, “While it is not yet clear how the market will change, the commercialization of cannabis may also significantly affect drug-use behaviors. Commercialization implies motivated selling, which can lead to directed advertisements that promote and encourage consumption” (p. 43).

Jamaica, Mexico, Morocco, and other countries have expressed interest in changing their marijuana laws, moving to some form of legalization. Economics is often cited as the motivation for legalization.

Do you agree with the UNODC’s concern about the commercialization of marijuana? Why or why not?

The Problems of Drug Abuse

Drug Use in the Workplace

Employers have always been concerned about the impact of substance abuse on their workers and their businesses because drug use may undermine employee productivity, safety, and health (Frone 2004). It is estimated that 14 million U.S. workers meet the diagnostic criteria for substance dependence (Jacobson and Sacco 2012). Drug abuse cost American businesses $120 billion in lost productivity, due mainly to labor participation costs, participation in drug abuse treatment, incarceration, and premature death (ONDCP 2014).

In their examination of occupational risk factors for drug abuse, Scott MacDonald, Samantha Wells, and T. Cameron Wild (1999) found that problem drinking or drug use was linked to the quality and organization of work, drinking subcultures at work, and the safety of the workplace. Respondents reporting alcohol problems were more likely to have jobs involving repetitive tasks and dangerous working conditions. Respondents with alcohol problems were also more likely to drink with coworkers and experience some social pressure to drink. The same pattern was true for workers with drug problems: They considered their jobs “boring” or repetitive, they identified their job as dangerous, they experienced stress at work, or they were likely to be part of a drinking subculture at work. Among all factors they identified, the presence of a drinking subculture at work was the strongest risk factor for alcohol and drug abuse.

By occupation, the highest rates of current illicit drug use and heavy drinking were reported by construction workers (15%), sales personnel (11.4%), and food preparation, wait staff, and bartenders (11.2%) (U.S. Department of Labor 2014). Among employed adults, White, non-Hispanic males between the ages of 18 and 25 who have less than a high school education are likely to report the highest rates of heavy drinking and illicit drug use (U.S. Department of Labor 2003).

Problem Drinking Among Teens and Young Adults

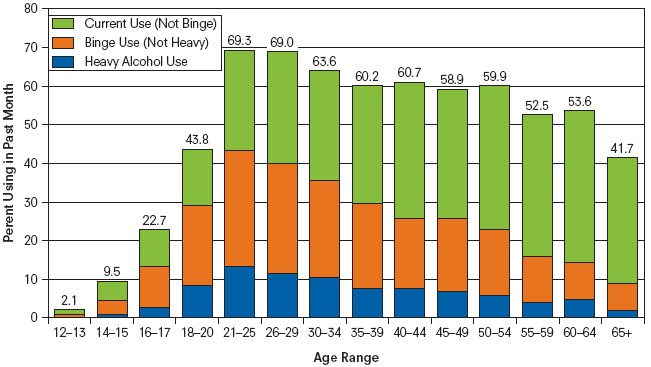

For 2013, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reported that the highest prevalence of binge drinking (drinking five or more drinks within a few hours or within one sitting) was for young adults aged 21 to 25 (43.3%), followed by 26- to 29-year-olds (40%). Heavy drinking (five or more drinks on the same occasion on at least five different days in the past 30 days) was reported by 13.1% of those 21 to 25 years of age (SAMHSA 2014). See Figure 12.3 for a summary of heavy alcohol use among persons ages 12 and older for 2013.

An international comparative study on drinking trends among 15- and 16-year-olds revealed that teens in the United Kingdom were among those most likely to drink heavily and to experience intoxication. In 2003, 52% of boys and 56% of girls reported binge drinking in the past 30 days (Plant, Miller, and Plant 2005). From 1995 to 2003, although there was no significant increase in the proportion of boys engaging in binge drinking, researchers observed a sharp increase in the proportion of girls binge drinking since 1999. The rise in binge drinking among girls is consistent with recent reports documenting the increase in heavy episodic or binge drinking among young women in Britain. The majority of surveyed teens, 75%, reported that they had at some time “been drunk” in 2003. Researchers concluded that U.K. teenagers drink in ways that are potentially harmful and that binge drinking among U.K. teens is a matter of real concern (Plant et al. 2005).

Figure 12.3 Current, binge, and heavy alcohol use among persons aged 12 and older, by age, 2014

SOURCE: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014.

By the time they reach the eighth grade, nearly 50% of U.S. adolescents report having had at least one drink, and more than 20% report having been drunk (NIAAA 2003b). Underage drinkers account for nearly 20% of the alcohol consumed in the United States (Tanner 2003). In 2013, 16- to 17-year-olds had the highest rate of currently alcohol use (23%), followed by persons aged 14 or 15 (10%) and persons aged 12 or 13 (2%) (SAMHSA 2014).

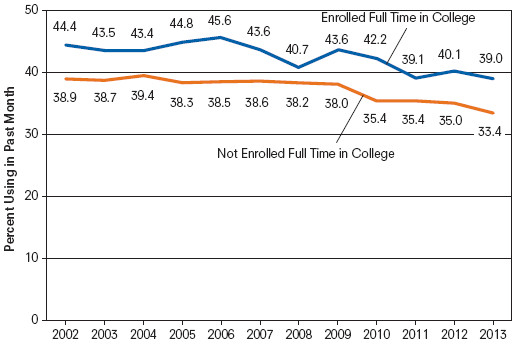

Binge drinking among college students has been called a major U.S. public health concern (Clapp, Shillington, and Segars 2000). (Refer to Figure 12.4 for a comparison of heavy drinking among those enrolled full-time in college and those who are not. Drinking rates are consistently higher for those enrolled full-time.) Henry Wechsler (1996) reported results from the 1996 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study, highlighting how binge drinking had become widespread among college students. In the Wechsler study, binge drinking was defined as five or more drinks in a row one or more times during a two-week period for men and four or more drinks in a row one or more times during a two-week period for women. The author explains that men, students younger than 24, fraternity and sorority residents, Whites, students in athletics, and students who socialize more are most likely to binge drink. On average, students who engaged in high-risk behaviors such as illicit drug use, unsafe sexual activity, and cigarette smoking were more likely to be binge drinkers. In contrast, students who were involved in community service, the arts, or studying were less likely to be binge drinkers (Wechsler 1996).

Binge drinking among college students has been called a major U.S. public health concern. According to the 2013 National Institute for Drug Use and Health, 43.3% of 21-25-year-olds reported binge drinking during the year (SAMSHA 2014).

REUTERS/Gerardo Garcia

Although the demographic and social correlates of college drinking have been consistently identified in many studies, attempts to explain the behavior through various sociological perspectives have been limited. Most prevalent in the literature are theories that identify drinking as part of the social learning process: addressing the role of peer groups, students’ attitudes, and perceptions as well as the social construction of drinking norms related to alcohol consumption. Similar social learning theories have also been linked to substance abuse (Durkin, Wolfe, and Clark 2005).

Access to alcohol is also related to problem drinking. Weitzman et al. (2003) reported a positive relationship between alcohol outlet density (number of bars and liquor stores near campus) and frequent drinking (drinking on 10 or more occasions in the past 30 days), heavy drinking (five or more drinks at an off-campus party), and drinking problems (self-reported).

The Task Force of the National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2010) concluded that 1,825 college students between the ages of 18 and 24 die each year from alcohol-related unintentional injuries, including motor vehicle crashes. About half a million students between the ages of 18 and 24 are unintentionally injured while under the influence of alcohol, and more than 600,000 students are assaulted by another student who has been drinking. In addition, the task force reports that 25% of college students report academic consequences (poor grades, poor performance, missing classes) as a result of their drinking, and more than 150,000 develop an alcohol-related health problem. Based on self-reports about their drinking, 31% of college students meet the criteria for alcohol abuse, and 6% meet the criteria for alcohol dependence (Task Force of the National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2010).

Brower (2002) explains that there is no evidence that drinking in college leads to later-life alcoholism or long-term alcohol abuse. He writes, “Real life is a strong disincentive for the kind of binge drinking that college students do” (Brower 2002:255). He suggests using the term episodic high-risk drinking to describe more accurately how college students drink: infrequently drinking a large quantity of alcohol in a short period. Brower and other researchers describe a “maturing out” of college drinking, shifting to moderate alcohol consumption with no associated alcohol use problems. The maturing-out process usually coincides with life changes such as employment, marriage, or a general shift to a conventional life style.

Figure 12.4 Heavy alcohol use among adults aged 18 to 22, by college enrollment: 2002 to 2013

SOURCE: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014.

Teen Substance Abuse

Punishment or Treatment?

Stricter federal policies have increased the number of men and women serving jail or prison time for drug-related offenses. As conflict and symbolic interaction theories suggest, drug laws are not enforced equally, with certain groups being singled out. Although most illicit drug users are White, Blacks constitute about 80% to 90% of all people sent to prison on drug charges (Fellner 2000). Nationwide, Black men are sent to state prison on drug charges at 13 times the rate of White men (Fellner 2000). Most women in prison are untreated substance abusers incarcerated for nonviolent offenses (Alleyne 2007). Drug enforcement usually targets urban and poor neighborhoods while ignoring drug use among middle- or upper-class people. Whereas our society treats middle- or upper-class drug use as a personal crisis, lower-class drug use is defined as criminal. Consider, for example, how the media reported the drug treatment of celebrities Lindsay Lohan and Britney Spears—was either referred to as a criminal?

Sasha Abramsky (2003) explains that with tougher drug laws, the U.S. drug war was taken away from public health and medical officials and placed into the hands of law enforcement and the courts. The notion that drug abuse is a disease was replaced with the idea that drug abuse is a crime. A punishment model has also been adopted in China, where its rehabilitation centers serve as forced labor camps punishing, not treating, addicts (Jacobs 2010). In contrast, the Netherlands defines drug abuse as a public health issue and has implemented harm reduction strategies, placing the priority on drug education and treatment rather than on punishment.

However, as overall crime rates began to decline, public support for the get-tough-on-drugs policy began to wane. Research conducted by the Pew Research Center revealed how 63% of Americans favored rolling back mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders and 67% believed drug use should be treated as a disease rather than as a crime (Desilver 2014).

Abramsky (2003) identified key legislative changes in several states. Arizona and California passed legislation that diverted thousands of drug offenders into treatment programs instead of prisons. In 1998, Michigan repealed its mandatory life sentence law for those caught in the possession of more than 650 grams of certain narcotics. In 2002, Michigan governor John Engler signed legislation that rolled back the state’s tough mandatory-minimum drug sentences. The Kansas Sentencing Commission proposed reforms of the state’s mandatory sentencing codes, along with expansion of treatment programs. The reforms were accepted in March 2003. Though California’s 2010 ballot initiative to legalize marijuana did not pass, that same year Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed into law a bill that reduced the penalty for marijuana possession from a misdemeanor to a nonarrestable infraction (e.g., a traffic ticket).

At the federal level, the Obama administration, through the ONDCP, has focused on addiction as a disease and has called for increases in drug prevention and treatment programs for all who need them, including drug-involved offenders. In 2010, President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act into law, reducing the disparity in the amounts of powder cocaine and crack cocaine required for the imposition of mandatory minimum sentences. In 2011, the U.S. Sentencing Commission voted to retroactively apply the new guidelines to individuals sentenced before the federal law was enacted. In 2014, Governor Jerry Brown signed the California Fair Sentencing Act, reducing the same sentencing disparity in crack versus powder cocaine offenses.

Federal Drug Laws and Criminal Sentencing

In Focus

Alcopops

Flavored alcoholic beverages, sugary fruit-flavored alcoholic beverages such as Mike’s Hard Lemonade and Bacardi Silver, have become popular with young drinkers. Though the alcohol content must be included in the packaging, some packaging makes these beverages appear more like nonalcoholic soft drinks or energy drinks than an alcoholic beverage containing 5% to 7% alcohol per volume. State lawmakers and parents have increasingly grown concerned about the popularity of these drinks, believing that these beverages contribute to underage drinking (Marshall 2007) and referring to them as “gateway” drugs (leading youth to more traditional alcoholic beverages).

A 2001 national poll revealed that 41% of all teens ages 14 to 18 had tried an alcopop, with twice as many 14- to 16-year-olds preferring them to beer or mixed drinks. When asked why they would choose these beverages over beer, wine, or liquor, teens reported that they liked the sweet taste of the drinks and the disguised taste of alcohol. Most surveyed teens believed the products were marketed to their age group (Alcohol Policies Project 2001).

However, there appears to be more concern about the growing consumption of these beverages among young girls. The American Medical Association released 2004 poll results that indicated that a third of all teen girls older than age 12 have tried alcopops. As part of an effort to urge then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to reclassify these beverages as hard liquor, Cinthya Luis, a high school senior and member of the San Diego Youth Council, explained, “Kids all over the state and the nation call these products ‘cheerleader beer’ and ‘girlie beer’ because they are so popular with underage girls—their sweet taste is designed to appeal to young drinkers.” Though Schwarzenegger vetoed the bill in 2005, the California State Board of Equalization voted to reclassify alcopops as distilled spirits (taxable at $3.30 per gallon) rather than beer (taxable at $0.20 per gallon). Prevention and youth advocates applauded the decision, hoping the higher cost would discourage underage consumption.

In addition to California, several other states, such as Arkansas, Illinois, and Nebraska, have considered reclassifying these beverages as hard liquor. Critics argue that these beverages are no different from beer, which contains 4% to 6% alcohol per volume. Maine and Utah have already reclassified these beverages as hard liquor.

Community, Policy, and Social Action

Federal Programs

Throughout the first part of this chapter, I have already referred to three U.S. offices: NIDA, the ONDCP, and the NIAAA. All three programs are federally funded.

The NIAAA was established after the passage of the Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act of 1970. Signed into law by President Richard Nixon, the legislation acknowledged alcohol abuse and alcoholism as major public health concerns. The law instructed the NIAAA to “develop and conduct comprehensive health, education, research, and planning programs for the prevention and treatment of alcohol abuse and alcoholism and for the rehabilitation of alcohol abusers and alcoholics” (NIAAA 2003a). Since then, the NIAAA’s mission has been revised to include support and implementation of biomedical and behavioral research, policy studies, and research in a range of scientific areas to address the causes, consequences, treatment, and prevention of alcoholism and alcohol-related problems (NIAAA 2003b).

NIDA was established in 1974 as the federal office for research, treatment, prevention, training services, and data collection on the nature and extent of drug abuse. Like the NIAAA, NIDA is part of the National Institutes of Health, the federal biomedical and behavioral research agency. NIDA’s stated mission is to bring “the power of science to bear on drug abuse and addiction” (NIDA 2003b). NIDA supports more than 85% of the world’s research on the health aspects of drug abuse and addiction.

The ONDCP is the newest federal drug program, operated through the White House. Established in 1988 through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, the ONDCP’s mission was to set national priorities, design comprehensive research-based strategies, and certify federal drug control budgets. According to the act, the purpose of the office was to prevent young people from using illegal drugs, reduce the number of drug users, and decrease the availability of drugs (ONDCP 2003). Ten years later, the ONDCP’s mission was expanded under the Reauthorization Act of 1998. Some of the legislative requirements included a commitment to a five-year national drug control program budget, the establishment of a parents’ advisory council on drug abuse, development of a long-term national drug strategy, and increased reporting to Congress on drug control activities (ONDCP 2003). The act also provided support for the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) program, coordinating local, state, and federal law enforcement drug control efforts.

Use of illegal drugs continues despite the efforts of these three lead agencies. And the War on Drugs comes with huge economic costs, with the Obama administration having requested $25.4 billion for prevention and treatment programs and law enforcement and incarceration for 2015.

Drug Legalization

The contemporary debate about the legalization of drugs emerged in 1988 during a meeting of the U.S. Conference of Mayors. Baltimore’s Kurt L. Schmoke called for a national debate on drug control policies and the potential benefits of legalizing marijuana and other illicit substances (Inciardi 1999). Proponents present several arguments for the legalization of drugs: current drug laws and law enforcement initiatives have failed to eradicate the drug problem, arresting and incarcerating individuals for drug offenses does nothing to alleviate the drug problem, drug crimes are actually victimless crimes, legalization will lead to a reduction in drug-related crimes and violence and improve the quality of life in inner cities, and legalization will also eliminate serious health risks by providing clean and high-quality substances (Cussen and Block 2000; Silbering 2001). Many supporters of legalization argue that drugs should be legalized based on the libertarian legal code (Trevino and Richard 2002), namely that the legalization of drugs would give a basic civil liberty back to citizens by granting them control over their own bodies (Cussen and Block 2000).

The term legalization is often used interchangeably with another term, decriminalization. The terms vary in the extent to which the law can regulate the distribution and consumption of drugs. In general, decriminalization means keeping criminal penalties but reducing their severity or removing some kinds of behavior from inclusion under the law (e.g., eliminating bans on the use of drug paraphernalia). Some would support regulating drugs in the same way alcohol and tobacco are regulated, whereas others would argue for no restrictions at all. Legalization suggests removing drugs from the control of the law entirely (Weisheit and Johnson 1992).

Several European countries including Portugal, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland have moved toward drug legalization or decriminalization in some form. The country most identified with liberal drug policies is the Netherlands. Since the mid-1970s, Netherlands coffee shops have been allowed to sell marijuana products. Though possession and sale of marijuana are not legal, in practice sales through these shops are not prosecuted, and buyers (18 years of age or older) are not prosecuted for possession of small (personal use) amounts.

In the United States, drug legalization is generally opposed by the medical and public health community (Trevino and Richard 2002). The American Medical Association has consistently opposed the legalization of all illegal drugs, arguing that most research shows drugs, particularly cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines, to be harmful to an individual’s health. Opponents charge that drug use is a significant factor in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, and drug users are more likely to engage in risky behaviors and in criminal activity (Trevino and Richard 2002). The DEA has also been clear about its opposition to drug legalization, citing concerns about potential increases in drug use and addiction, drug-related crimes, and costs related to drug treatment and criminal justice.

In the 1990s, the drug debate began to change, with legalization proponents advocating a “harm reduction” approach. Many opposed to legalization began to accept aspects of the harm reduction approach. Harm reduction is a principle suggesting that “managing drug misuse is more appropriate than attempting to stop it all together” (Inciardi 1999:3). Proponents acknowledge that current drug policies are not working, but they are still not in favor of full decriminalization (McBride, Terry, and Inciardi 1999). The harm reduction approach emphasizes treatment, rehabilitation, and education (McBride et al. 1999), including advocacy for changes in drug policies (such as legalization), HIV/AIDS-related interventions, broader drug treatment options, counseling and clinical case management for those who want to continue using drugs, and ancillary interventions (housing, healing centers, advocacy groups) (Inciardi 1999). Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for a discussion on the legalization of marijuana.

Exploring social problems

Support of the Legalization of Marijuana

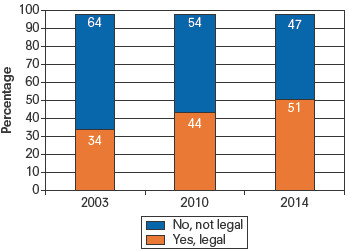

Figure 12.5 Percentage who support legalization of marijuana, 2003, 2010, and 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from Saad 2014.

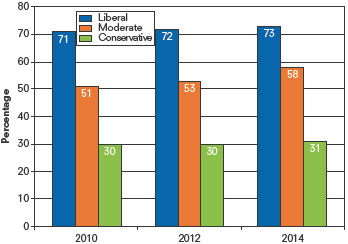

Figure 12.6 Percentage who support legalization of marijuana, by political views, 2010, 2012, and 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from Saad 2014.

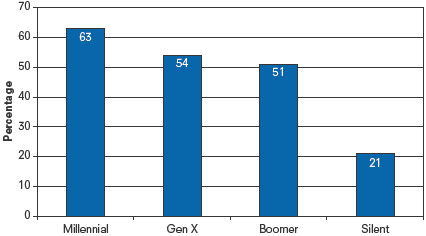

Figure 12.7 Percentage who support legalization of marijuana by age cohort, 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from Motel 2014.

What Do You Think?

Though general support for the legalization of marijuana has shifted in recent years (refer to Figure 12.5), there is still some variation by social groups (refer to Figures 12.6 and 12.7).

Based on Figure 12.6, compare the differences in legalization support for the three groups presented. Which group’s level of support changed the most? Which group’s level of support changed the least?

How would you describe the difference in legalization support by generational group (Millennials born 1981–1998, Gen X born 1966–1980, Boomers born 1948–1964, and Silent born 1928–1945) as reported in Figure 12.7? How does age affect level of support?

From a sociological perspective, how are attitudes about marijuana legalization dependent upon social or structural factors?

Drug Treatment and Prevention Programs

Individual Approaches

Drug addiction is a “treatable disorder” (NIDA 2003b). Traditional treatment programs focus on treating the individual and his or her addiction. The ultimate goal of treatment is to enable users to achieve lasting abstinence from the drug, but the immediate treatment goals are to reduce drug use, improve users’ ability to function, and minimize their medical and social complications from drug use.

Treatment may come in two forms: behavioral treatment includes counseling, support groups, family therapy, or psychotherapy; medication therapy, such as maintenance treatment for heroin addicts, may be used to suppress drug withdrawal symptoms and craving. Short-term treatment programs can include residential treatment, medication therapy, or drug-free outpatient therapy. Long-term programs (longer than six months) may include highly structured residential therapeutic community treatment or, in the case of heroin users, methadone maintenance outpatient treatment. Research conducted during the past 25 years indicates that treatment does work to reduce drug intake and drug-related crimes. Patients who stay in treatment longer than three months have better outcomes than do people who undergo shorter treatments (NIDA 2003b).

Workplace Strategies

Certain employers, such as employers in the transportation industry and organizations with federal contracts in excess of $100,000, are required by law to have drug-free workplace programs. The federal government, through the Drug Free Workplace Program, also encourages private employers to implement such programs in an effort to reduce and eliminate the negative effects of alcohol and drug use in the workplace (SAMHSA 2003b). It is estimated that more than 80% of employers implement drug testing at the workplace. After implementing a drug-free workplace program, employers, unions, and employees are likely to see a decrease in administrative work losses (sick leave abuse, health insurance claims, disability payments, and accident costs), hidden losses (poor performance, material waste, turnover, and premature death), legal losses (grievances, threat to public safety, work site security), and costs of health and mental health care services (SAMHSA 2003a).

Drug-testing programs have been subject to lawsuits during the past decade for challenging the employees’ right to privacy and their constitutional freedom from unreasonable searches by the government (SAMHSA 2003b). There have also been challenges to the accuracy of drug tests. Critics have asserted a positive test does not always correlate with poor job performance, a criterion for assessing the adverse effects of drugs (Klingner, Roberts, and Patterson 1998). Consistent with conflict theories on drug use, some have argued that drug testing promotes various political agendas and reflects the manipulation of interest groups that market and sell drug testing and security services (Klingner et al. 1998). Yet many U.S. companies consider drug-testing programs part of an effective policy against substance abuse among workers (Hoffman and Larison 1999). Drug testing is also part of a preventative strategy, as the U.S. Department of Labor (2007) reports that between 10% and 20% of workers who die on the job test positive for alcohol or other drugs.

Paul Roman and Terry Blum (2002) report that employee assistance programs (EAPs) are the most common intervention used in the workplace to prevent and treat alcohol and other drug abuse among employees. The primary goal for many of these programs is to ensure that employees maintain their employment, productivity, and careers. These EAPs usually include health promotion, education, and referral to abuse treatment as needed. Most of these programs do not target the general workplace population; rather, services are directed to those already affected by a problem or in the early stages of their abuse. There is some evidence of the effectiveness of these programs, returning substantial proportions of employees with alcohol problems to their jobs (Roman and Blum 2002). In their 2012 study, Jodi Jacobson and Paul Sacco noted how EAPs are in a prime position to reach out to working adults and engage them in education and treatment for alcohol and drug abuse problems earlier than traditional community-based substance abuse programs. They also stated how EAPs could better target racial or ethnically diverse worker groups.

The New Heroin Addicts

Campus Programs

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that drug testing in schools is legal for student athletes (1993) and for students in other extracurricular activities (2002). In both rulings, the Court stated that drug screenings play an important role in deterring student drug use.

However, a national study of 76,000 high school students reported no significant difference in drug use among students in schools with testing versus students in schools without testing. Researchers Ryoko Yamaguchi, Lloyd Johnston, and Patrick O’Malley (2003) reported that 37% of 12th graders in schools that test for drugs said that they had smoked marijuana in the previous year, compared with 36% of 12th graders in schools that did not test. In addition, 21% of 12th graders in schools with testing reported that they had used illicit drugs (cocaine or heroin) in the previous year compared with 19% of 12th graders in schools without drug screenings. The study found that only 18% of schools did any kind of drug screening between 1998 and 2001. Large schools (22.6%) reported more testing than did smaller schools (14.2%). Most drug tests were conducted in high schools. The study did not compare schools that conducted intensive regular screenings with those that occasionally tested for drugs. The study indicated that education, rather than testing, may be the most effective weapon against abuse (Winter 2003).

Colleges and universities play critical roles in the prevention and early intervention of drug use, as they are able to implement large-scale prevention and educational programming to reach young adult students. In their review of 94 college drug prevention programs, Andris Ziemelis, Ronald Buckman, and Abdulaziz Elfessi (2002) identified three prevention models that produced the most favorable outcomes of drug use prevention efforts. The first model includes student participation and involvement, such as volunteer services, advisory boards, or task forces, to discourage alcohol or other drug use or abuse. The researchers documented how these activities reinforce students’ beliefs that they are in control of the outcomes in their lives and that their efforts and contributions are valued. This model encourages student ownership and development of the program. The second model includes educational and informational processes, such as instruction in classes, bulletin boards and displays, and resource centers. The most effective informational strategies were those that avoided coercive approaches but instead encouraged interactive communication between students and professionals on campus. The last model includes efforts directed at the larger structural environment, changing the campus regulatory environment and developing free alternative programming, such as providing alcohol-free residence halls or mandatory alcohol and drug abuse classes as part of campus intervention. In general, models that discouraged or deglamorized alcohol and drug use were associated with better outcomes than were those that merely banned or restricted substance use (Ziemelis et al. 2002).

Community Approaches

In 1997, the Drug-Free Communities Act became law. The act was intended to increase community participation in substance abuse reduction among youth. The program is currently directed by the White House’s ONDCP. The program supports more than 700 coalitions of youth; parents; law enforcement; schools; state, local, and tribal agencies; health care professionals; faith-based organizations; and other community representatives. The coalitions, such as Project Northland, rely on mentoring, parental involvement, community education, and school-based programs for drug prevention and intervention.

Based in northern Minnesota, Project Northland was the largest community trial in the United States to address the prevention of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among adolescents (Williams and Perry 1998). Adopting a holistic approach, the project assumed that prevention efforts should be directed at adolescents and their immediate social environment (family, peers, friends) and should include larger peer groups (teachers, coaches, religious advisers) as well as the broader community of businesses and political leaders. The project was recognized for its programming by SAMHSA, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Department of Education.

Project Northland included youth participation and leadership, parental involvement and education, community organizing and task forces, media campaigns, and school curriculum as part of its strategies for alcohol use prevention. The program included two phases. Phase 1 focused on strategies to encourage adolescents not to use alcohol. Phase 2 emphasized changing community norms about alcohol use, reducing the availability of alcohol among high school students, and adopting a functionalist approach in reinforcing community norms and boundaries. Community strategies included making compliance checks of age-of-sale laws (coordinated through local police departments), holding training sessions for responsible beverage servers at retail outlets and bars, and encouraging businesses to adopt “gold card” programs where discounts are provided to students who pledge to remain free of alcohol. At the end of Phase 2, significant differences between the intervention and comparison groups were observed. The rates of increase in underage drinking were lower among the intervention students (Perry et al. 2002). In 2002, Project Northland was implemented internationally. First-year program data from primary and secondary schools in Croatia reveal that Project Northland was effective in increasing dialogue between Croatian students, parents, and teachers about students’ actual use of alcohol (Abatemarco et al. 2004).

The Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA) is a nonprofit organization that provides technical assistance and training to community-based coalitions. The organization was established in 1992 by Jim Burke and Alvah Chapman and currently serves more than 5,000 antidrug coalitions in 18 countries. The program provides community groups with lobbying handbooks, alerts on drug-related legislation, funding information, and coalition training on various drug abuse topics. One CADCA affiliate is California’s Ashland Cherryland Together. Through community data collection, the coalition recognized how prescription drugs were being improperly used or shared or resold on the illegal market. The coalition identified the need for a permanent, policy change that would provide access to and awareness of convenient disposal of unused medication. The community partners supported the adoption of the Safe Medication Disposal Ordinance in July 2012. The first law of its kind, it brings together government, medical, environmental, and community organizations in a comprehensive campaign around the effects of prescription drug misuse. There are more than 30 drug disposal locations throughout the community (CADCA 2014).

Voices in the Community

Shilo Murphy

Syringe or needle exchange programs emerged at the height of the AIDS epidemic to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS and other blood-borne diseases. The programs also facilitate access to drug treatment and health care services. The first needle exchange program was introduced in Amsterdam, Holland, to reduce the risk of hepatitis B and HIV among injecting drug users. These programs also serve a public health function, reducing accidental needle-stick incidents among the general public.

In 1997, Shilo Murphy was a homeless addict when he found the University District Needle Exchange in Seattle, Washington. He says he began volunteering for the program to change the life conditions of his friends and family. Murphy currently serves as the program’s executive director.

The needle exchange was renamed the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance (PHRA) in 1999. PHRA, according to Murphy, is “a user-run organization, so active drug users make all of our decisions.... We’re a living, breathing organization in that we constantly change our policies by the needs of people we serve and our bosses are the people we serve” (quoted in Gunawan 2014). The alliance distributes approximately 3 million needles each year and is supported by more than 100 volunteers in three Western Washington counties.

Murphy explains,

I think [needle exchanges are] important so that a new generation of drug users don’t have to go through the pain and suffering when we had to bury so many people who overdosed, so many people who committed suicide because society hated them so much... I wanted another generation to have the opportunity to have a better life. (quoted in Gunawan 2014)

Murphy describes his clients as members of a community, members of his family, and individuals who are precious and worthy of love. “[Exchange volunteers] will always follow our hearts and we always take the knowledge and experience of the drug users we serve to give their lives just a little better place” (Murphy 2014).

As of 2013, it was estimated that there were needle exchange sites in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

Identify other functions or benefits of needle exchange programs.

Sociology at Work

Public Health

Erika Meyer—Class of 2011

Undergraduate Majors: Sociology, Global Studies

Public health is “the science of protecting and improving the health of families and communities through promotion of healthy lifestyles, research for disease and injury prevention and detection and control of infectious diseases” (CDC Foundation 2014). Unlike doctors and nurses who treat the sick or injured, public health professionals also address disease prevention through educational programs, research, and public policy.

Educational requirements for employment in the public health sector vary. A bachelor’s degree is the minimum requirement to become a health educator or community worker; but to work as an epidemiologist (studying the patterns and causes of disease and injury in humans), you will need at least a master’s degree (U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014).

After earning her bachelor’s degree in Sociology and her master’s in Public Health, Erika Meyer now works as a program associate at Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network (TEPHINET). A partner with the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, TEPHINET manages and provides resources to 59 field epidemiology training programs (FETPs) in over 80 countries. Erika’s primary work involves coordinating the accreditation process for the FETPs. She also serves as a project manager for several other projects, including working with CDC’s Infection Disease Surveillance and Response Team to build an online disease detection and reporting course for community health workers in Africa.

Erika says that she engages her sociological imagination most when she’s designing training and programs for field epidemiologists in countries and cultures very different from her own.

For example, in response to the Ebola epidemic, CDC and TEPHINET are putting together basic surveillance trainings for frontline staff—nurses, community healthcare workers, labor and delivery staff—to teach them about disease reporting. They not only need to know what kinds of symptoms to look for (including Ebola, but also influenza, polio, cholera, etc.), but who to tell that information to and what the data feedback loop should look like. We have to work with the Ministries of Health in the 10 countries to make sure this is a culturally relevant and sensitive training, and that there is the administrative capacity to handle what we are hoping will be an upswing in reporting of outbreaks. We have to carefully navigate the political and social structures that hold decision-making power and sway. The Ebola epidemic provides a salient case study of a “public issue,” and my project has to respect the post-colonial scars affecting each country as they response to a crisis of this magnitude.

If your school does not have any courses or programs in a field you’re interested in, Erika suggests doing the research on your own as she did.

I sought out summer and school-year internship opportunities that fit my academic and professional interests, and also had the opportunity to spend a semester abroad studying global public health, which afforded me incredible personal and academic growth. I found this to be a great way for me to “try on” the discipline academically, and it really piqued my interest to continue this work in graduate school and as a career.

Chapter Review

- 12.1 Explain how the different sociological perspectives explain alcohol and drug problems

Functionalists argue that society provides us with norms or guidelines on alcohol and drug use. A set of social norms identifies the appropriate use of drugs and alcohol. Conflict theorists address how powerful political and business interest groups have made intentional decisions about which drugs are illegal. Feminists argue that theorists and practitioners in the field of alcohol and drug abuse have ignored experiences unique to women and other marginalized groups. The interactionist perspective examines how drug abuse is learned from others; it also addresses how individuals or groups are labeled abusers and how society responds to them.

- 12.2 Describe how the social structure regulates drinking

Studies suggest that ethnic/racial groups have different sets of norms and values regulating drinking, such as encouraging moderate alcohol consumption on social events or celebrations. The consumption of alcohol among women is also moderated by social norms. Women’s roles of wife and mother may discourage alcohol intake.

- 12.3 Identify the correlates of Ecstasy use among college students

Some of the correlates identified in Boyd et al.’s 2003 study include: White students were more likely to report lifetime Ecstasy use than were African American or Asian students. Those who identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual were more likely to report lifetime, annual, or past-month Ecstasy use than were heterosexual students. Students with a grade point average (GPA) of 3.5 or higher were consistently less likely to have used Ecstasy in the past year or their lifetime than were students with GPAs below 2.5.

- 12.4 Assess the theory that college students mature out of heavy or binge drinking

According to researchers, maturing-out is a natural process related to a general shift toward a conventional life style, employment, and/or marriage.

- 12.5 Examine the pros and cons of the drug legalization movement

Opponents charge that drug use is a significant factor in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, and that drug users are more likely to engage in risky behaviors and in criminal activity. There are also expressed concerns about drug-related crimes and costs related to drug treatment and criminal justice. Proponents acknowledge that current drug policies are not working, emphasizing a harm reduction approach that focuses on treatment, rehabilitation, and education.

Key Terms

- alcoholism, 334

- decriminalization, 347

- differential association, 332

- drug abuse, 333

- drug addiction, 333

- episodic high-risk drinking, 342

- legalization, 347

- role strain, 330

Study Questions

- How are sociological explanations of drug abuse different from biological or psychological approaches?

- From a functionalist perspective, explain how the social structure contributes to drug use.

- Explain how stereotypes of drug use and abusers influence how specific individuals and groups are labeled abusers and how society responds to them.

- Define drug abuse and drug addiction.

- Is drinking a problem among teens and young adults? Why or why not?

- Define drug legalization. Would it be effective in reducing the amount of drug use? Why or why not?

- What treatment programs are available to drug users? What type of prevention programs?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.