Chapter 11 The Media

Learning Objectives

- 11.1 Define media

- 11.2 Explain how the different sociological perspectives examine social problems related to the media

- 11.3 Review the importance of the digital divide

- 11.4 Explain the relationship between media technology and a boundary-less workplace

- 11.5 Identify the importance of media literacy

Imagine that you wake up tomorrow in a sort of “Twilight Zone” parallel society where everything is the same except that media do not exist: no television, no movies, no radio, no recorded music, no computers, no Internet, no books or magazines or newspapers.

—Croteau and Hoynes (2000:5)

What would your life be like without the media? Without communication, and the media to communicate with, there would be no society. The term media is the plural of medium, derived from the Latin word medius, which means middle. A medium is a method of communication—television, telephone, cable, Internet, radio, or print—between (or in the middle of) a sender and a receiver. But taken all together, the media, as defined by David Croteau and William Hoynes (2000), are the “different technological processes that facilitate communication between the sender of the message and the receiver of that message” (p. 7).

Communication is a basic social activity (Seymour-Ure 1974). It is impossible not to communicate and not to come in contact with the media. Today’s college students are described as “digital natives” who are technology dependent and capable of accessing information instantly and using many technological devices for everyday living and communication (Black 2010). Take a moment and inventory the number of devices you own—cell phone, laptop, desktop, e-reader, iPod, digital camera? It is estimated that by the age of 21, Millennials have averaged 10,000 hours playing video games, 2,000 hours watching television, 10,000 hours on the cell phone, and have sent or read 200,000 emails (Barnes, Marateo, and Ferris 2007).

The media reflect “the evolution of a nation that has increasingly seized on the need and desire for more leisure time” (Alexander and Hanson 1995:i). Technological developments have increased our range of media choices, from the growing number of broadcast and cable channels to the ever-increasing number of Internet websites. New technologies have also increased our viewing control of and access to the media. For example, technology allows us to choose where and when we want to see a recent film. Are you taking a long road trip? You can download your favorite movie to your notebook or your phone and watch it on the road. Need to access your e-mail? You can check e-mail with a wireless connection in your classroom or with your phone from nearly any location. In fact, u cn comnC8 w/yr F W txt msgN A3 (translation: You can communicate with your friends with text messaging anytime, anywhere, anyplace). As Croteau and Hoynes (2001) observed, “We navigate through a vast mass media environment unprecedented in human history” (p. 3).

Yet, the media have been blamed for creating and promoting social problems and accused of being a problem themselves. Media critics have expressed concern about the highly controlled process by which the images that we see are conceived, produced, and disseminated by media conglomerates. Social researchers and policy makers have identified the unequal advantage some social groups have over others in our increasingly high-tech media environment. Are we losing our individual rights and privacy for the sake of increasing connectivity? Before we review the media and their related social problems, we first examine the media from a sociological perspective.

Sociological Perspectives on the Media

Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists examine the structural relationship between the media and other social institutions. Even before the content is created, political, economic, and social realities set the stage for media content. The media are shaped by the social and economic conditions of American life and by society’s beliefs about the nature of men and women and the nature of society (Peterson 1981). The first American printing press arrived in Boston along with a group of Puritans fleeing England in 1638. The press became an instrument of religion and government, used to print a freeman’s oath that presented the conditions of citizenship in this new country, as well as an almanac and a book of hymns (Peterson 1981).

Through electronic and print messages, the media continue to frame our understandings about our lives, our nation, and our world. The media serve as a link between individuals, communities, and nations. They help create a collective consciousness, a term used by Émile Durkheim to describe the set of shared norms and beliefs in a society. The mass media provide people with a sense of connection that few other institutions can offer. Live media events, such as the Olympics, the Super Bowl, or the Oscars, are set off from other media programs. People gather in groups to watch, they talk about what they see, and they share the sense that they are watching something special (Schudson 1986). News events captured by the media, such as the 2012 Summer Olympic games, the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, or the 2014 demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri, connect a nation and even the world.

An estimated 18.6 million U.S. households watched television coverage of the 2011 royal wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton. In addition to network and cable television programming, the ceremony was streamed live online via Facebook, Yahoo, and Hulu. iPad and iPhone apps also allowed fans to follow the royal nuptials.

Samir Hussein / Getty Images

In particular, television has contributed to a corresponding nationalization of politics and issues, taking local or regional events and turning them into national debates. Socially and politically, the media make our world smaller. Thanks to various forms of social media, the world watched as millions of Egyptians converged on Tahrir Square in 2011 demanding the overthrow of the regime of President Hosni Mubarak. Mubarak resigned after 18 days of demonstrations. Facebook and Twitter are credited with unifying protestors and ultimately shaping the political debate.

Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter were credited with helping organize Egyptian protestors during the 2011 Arab Spring.

© Sallie Pisch / Demotix/Demotix/Demotix/Corbis

The media have been accused of creating serious dysfunctions and social problems in society. Research has documented the link between viewing of media violence and the development of aggression, particularly among children who watch dramatic violence on television and film. Television has been called the “other parent” or the “black box,” accused of draining the life and intelligence out of its young viewers. Popular media culture has been accused of undermining our educational system and subverting traditional literacy (Postman 1989). Public health studies have documented the link between television viewing and poor physical health among children and adults. The one thing television viewers seem to do while watching television is eat, and the danger is in what they choose to eat and drink—unhealthy snack foods or high-calorie drinks (Van den Bulck 2000).

Conflict Perspective

The media, says Noam Chomsky (1989), are like any other businesses. The fundamental principle in American media is to attract an audience to sell to advertisers. Yes, you read that correctly. Commercial television and radio programming depend on advertising revenue, and in turn, the networks promise that you, the consumer audience, will buy the advertisers’ products. “The market model of the media is based on the ability of a network to deliver audiences to these advertisers” (Croteau and Hoynes 2001:6).

In the United States, media organizations are likely to be part of larger conglomerates where profit making is the most important goal (Ball-Rokeach and Cantor 1986). Since the very beginning of mass communications, ideas, information, and profit have mixed. The first books printed in the colonies may have been devoted to religion, but the printers made money (Porter 1981). The media, according to conflict theorists, can only be fully understood when we learn who controls them.

One of the clearest, and some say most problematic, trends in the media is the increasing consolidation of ownership. The corporate media play a major role in managing consumer demand, producing messages that support corporate capitalism, and creating a sense of political events and social issues (Kellner 1995). In 1984, more than 50 corporations controlled most of our newspapers, magazines, broadcasting, books, and movies. By 1997, Ben Bagdikian reported that there were 10 media giants. The top five entertainment multinational conglomerates controlling the media for 2011 are listed in Table 11.1. These companies are truly multimedia corporations, producing movies, books, magazines, newspapers, television programming, music, videos, toys, and theme parks in the global marketplace. Under this increasing media consolidation, women- and minority-owned broadcasting has declined. People of color own only 3% of commercial television stations (Wade 2008).

SOURCE: CNN Money 2011.

NOTE: For more information about these media companies, visit the website “Who Owns What,” sponsored by the Columbia Journalism Review. Log on to the SAGE edge select companion site, Chapter 11, at http://edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e for a link.

Miller (2002) warned that the most corrosive influence of the 10 media conglomerates cited by Bagdikian (1997) was their impact on journalism. Journalism has traditionally been referred to as the fourth estate, an independent institutional source of political and social power that monitors the actions of other powerful institutions such as politics, economics, and religion. However, conflict theorists remind us that someone is in charge of the fourth estate. Those who control the media are able to manipulate what we see, read, and hear. The media, serving the interest of interlocking state and corporate powers, frame messages in a way that supports the ruling elite and limits the variety of messages that we read, see, and hear (Chomsky 1989).

Edward Jay Epstein (1981) reveals that what we consider news is not the product of chance events; “it is the result of decisions made within a news organization” (p. 119). He explains that the crucial decisions on what constitutes news—what will and won’t be covered—are made not by the journalists but by executives of the news organization. Although the public expects news reporters to act like independent fair-minded professionals, reporters are employees of corporations that control their hiring, firing, and daily management (Bagdikian 1997). News executives are in control of the selection and deployment of specific reporters, the expenditure of time and resources for gathering the news, and the allocation of space for the presentation of news (Epstein 1981). And because they are economically motivated, news organizations are mindful of their audiences’ preferences and try to cater to those preferences as much as possible (Baron 2006).

Regina Branton and Johanna Dunaway concluded that audience preferences and newspaper profit motives result in differences between English and Spanish news coverage of immigration in the United States. In their 2008 study, Spanish-language news outlets generated a larger volume of immigration coverage than English-language outlets. On the other hand, English-language news media were more likely to focus on negative aspects of immigration than Spanish-language media outlets. Both patterns, according to the researchers, are motivated by profit and the desire to satisfy their different target audiences. Branton and Dunaway suggest that conflicting media coverage may even contribute to the differences in immigration attitudes between Anglos and Latinos.

Who Owns the Media?

Feminist Perspective

Douglas Kellner (1995) says that the media represent “a contested terrain, reproducing on the cultural level the fundamental conflicts within society” (p. 101). Feminist theorists attempt to understand how the media represent and devalue women and minorities. This perspective examines how the media either use stereotypes disparaging women and minorities or completely exclude them from media images (Eschholz, Bufkin, and Long 2002).

One of the most important lessons young children learn is expected gender roles, learning masculine versus feminine behaviors. Although these lessons are taught by parents and teachers, a significant source of cultural gendered messages is television programs (Powell and Abels 2002). Regular exposure to television’s stereotypical gender roles has been associated with young children having more stereotypical beliefs about masculine and feminine characteristics and activities (Signorielli and Lears 1992). In his analysis of children’s programming, Mark Barner (1999) found that women are typically portrayed in passive roles as housewives, waitresses, and secretaries, whereas men are seen in active roles as construction workers or doctors. Rivadeneyra and Ward (2005: 454) argue, “If women are seldom portrayed as problem solvers, heroines, and working mothers, and if men are rarely depicted as nurturant and sensitive, viewers’ own self-conceptions, aspirations and gender ideologies may become equally constrained.”

Feminist scholarship demonstrates how the media undermine women, particularly those who challenge traditional gender roles (Gibson 2009). In 2006, Katie Couric made history when she debuted as the first woman to solo anchor a major network newscast. Her debut and performance, according to Katie Gibson (2009), was critiqued in the media through a sexualized frame. By focusing primarily on her body and her appearance (her hair style, legs, and fashion), the media objectified Couric and undermined her as a legitimate news professional.

During the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, media reports addressed Governor Sarah Palin’s lack of political experience, but also focused on her appearance and her beauty pageant background.

© EdStock/iStock

Researchers have identified how female political candidates receive different attention from their male counterparts. News reports focus on political women’s physical appearance, lifestyle, and family life rather than on campaign issues and how women are the targets of negative coverage regarding their lack of experience and knowledge (Wasburn and Wasburn 2011). Coverage about a female candidate’s political positions will feature women’s topics such as abortion, child care, or education as opposed to men’s issues such as the economy or national security. Philo Wasburn and Mara Wasburn (2011), in their analysis of media coverage of Governor Sarah Palin’s vice presidential campaign, concluded that “with respect to the coverage of political women, the political culture of America’s commercial media remained largely unchanged through decades of election cycles” (p. 1039). Though there was more coverage of Palin than Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential candidate, Palin was objectified by the media and treated as a sex object through references to her beauty queen background, her appearance, and her wardrobe. There was frequent mention of her lack of national and global political experience, and policy coverage was focused on her take on women’s issues.

Body Evolution

Interactionist Perspective

In what they tell us and what they choose not to tell us, the media define our social world (McNair 1998). The interactionist perspective focuses on the symbols and messages of the media and how the media come to define our “reality.” It might be best to view the media, as Michael Gurevitch and Mark Levy (1985) suggest, as “a site on which various social groups, institutions, and ideologies struggle over the definition and construction of social reality” (p. 9).

The mass media become the authority at any given moment for “what is true and what is false, what is reality and what is fantasy, what is important and what is trivial” (Bagdikian 1997:xliv). The mass media define what events are newsworthy. The first criterion is proximity; events happening close are more newsworthy than those happening at a greater distance. Second, deviation is an important criterion. Events that can be reported as disruptions (natural disasters, unexpected deaths, murders), deviations from cultural or social norms of behavior (especially sexual, e.g., philandering clergy or politicians), and lifestyle deviance (alternative lifestyle reports) make the news (Galtung and Ruge 1973).

Sociologist Herbert Gans (1979) explained that the news isn’t about just anyone; it is usually about “knowns.” Women and men identified by their position in government or their fame and fortune are automatically newsworthy. Knowns are elites in all walks of life, but especially from politics, the entertainment industry, and sports. Incumbent presidents appear in the news most often. The president is the only individual whose routine activities are noteworthy. (When was the last time that a news crew followed your every move?) In recent years, “celebutantes” (daughters from wealthy or famous families), such as the Kardashian sisters, have been deemed newsworthy by the media, with their every move and fumble chronicled.

One of the biggest news stories of the late 20th century was the death of Princess Diana. The facts and circumstances of her 1997 death and the fairy-tale life that preceded it conformed to all the criteria of newsworthiness. Although it occurred in France, her death involved cultural proximity: Princess Diana was a worldwide celebrity. The nonstop coverage of her life and death began as a story of celebrity fascination but ended as an international tragedy (McNair 1998). Shortly after Princess Diana’s death, Mother Teresa, a renowned humanitarian, died. Although Mother Teresa’s death was a news story, it never got the same attention and coverage as the death of Princess Diana did. As journalist Daniel Schorr (1998) said, the difference between the two women’s lives was “the difference between a noble life well lived and a media image well cultivated. . . . Mother Teresa was celebrated, but was not a celebrity” (p. 15).

The mass media play a large role in shaping public agendas by influencing what people think about (Shaw and McCombs 1997) and, ultimately, what people consider a social problem (Altheide 1997). David Altheide (1997) describes the news media as part of the “problem-generating machine” produced by an entertainment-oriented media industry. The news informs the public, but its message is also intended to serve as entertainment, an opportunity for voyeurism, and a “quick fix” rather than providing an understanding of the underlying social causes of the problem.

Altheide (1997) argues that the fear pervasive in American society is mostly produced through messages presented by the news media. The disproportionate coverage of crime and violence in the news media affects readers and viewers (Glassner 1997). Despite evidence that Americans have a comparative advantage in regard to diseases, accidents, nutrition, medical care, and life expectancy, American women and men perceive themselves to be at greater risk than do their counterparts elsewhere and express fears about this (Altheide 1997). In a national poll, respondents were asked why they believe the country has a serious crime problem. About 76% said they had seen serious crime in the media, whereas only 22% said they had had a personal experience with crime (Glassner 1997). In a study of 56 local news programs, crime was the most prominently featured subject, accounting for more than 75% of all news coverage in some cities (Klite, Bardwell, and Salzman 1997).

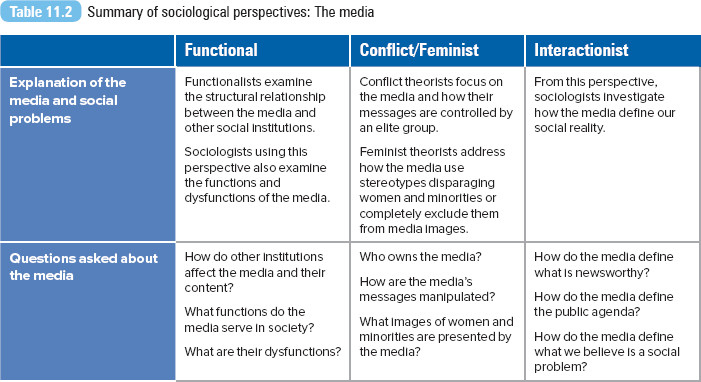

For a summary of sociological perspectives, see Table 11.2.

Growing Up Online

Taking a World View

Women’s Feature Service, New Delhi, India

Established in 1978, the Women’s Feature Service (WFS) began as an effort to include gender analyses and views in the media. The international news service is directed and staffed by women, syndicating 250 to 300 articles a year in print and electronic media. By gathering and providing access to these stories about women’s lives, WFS seeks to build awareness about women’s lives, rights, and concerns (Women’s Feature Service 2014).

WFS exists because of the felt need for a gender balance in news coverage and because of dissatisfaction about the ways in which news organizations—in India and elsewhere—treat news coverage about women. Often, the media either ignore important stories altogether, relegate reporting to obscure places in the newspaper, or sensationalize incidents without examining the underlying context or causes. The media tend to focus on women only when it comes to “women’s issues,” forgetting that women also have an equal stake in so-called “male concerns” such as the budget, economy, globalization, agriculture, and conflict resolution. (Parekh 2001)

Women occupy about 36% of all reporting jobs based on an international survey of 59 nations (International Women’s Media Foundation 2010).

Pamela Phillopose served as WFS editor until 2014. As a journalist, she advocates the importance of telling people-centric stories.

In a country like India, where the well-being of an increasing number of people is being threatened, directly and indirectly, by reversals of all kinds, ranging from the food and environmental crises to global recessions, there is space for a more people-centric definition of journalism. We need more than ever media practitioners who travel beyond the confines of privileged enclaves, leaving behind the “big spenders” of metropolitan India, to tell their stories. We need media practitioners who have the knowledge, capacity and technological ability to communicate on the real issues of our times and speak truth to power in compelling ways. (Phillopose, quoted in Neupane 2014)

The news organization also sponsors international conferences on women-related issues and media workshops for journalists. WFS is based in New Delhi, India (Women’s Feature Service 2014).

From an interactionist’s perspective, how does the media define what is newsworthy? Is there a way to alter the media’s influence?

The Media and Social Problems

Loss of Privacy

Erving Goffman (1959) theorized that individuals practice impression management, creating a favorable impression of themselves to others. He argued that we maintain a distinction between a public self (performing on a front stage for the benefit of others) and a more private self (more natural and comfortable on the backstage). However the advent of social media has increasingly blurred the lines between public and private. “Before our children can walk or talk, we teach them to share. So it is no wonder that we have flocked to social media, a platform based on sharing, to share everything from our birth dates to films of our child’s birth,” said Julie Brill, commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) (quoted in Naoum 2012).

And in some cases you do not have a choice in what information you share. Documents leaked by former National Security Agency subcontractor Edward Snowden in 2013 confirmed how for years the agency was intercepting phone calls and online communications of American citizens. Under its PRISM program, the agency was gathering data on non-U.S. citizens through its access of Apple, Facebook, Google, Skype, and Yahoo servers. Though the agency was accused of violating the U.S. Constitution and several federal privacy laws, General Keith Alexander (NSA’s Chief) defended the program citing the Patriot Act. According to Alexander, the agency’s phone and Internet surveillance programs were essential to preventing terrorist acts around the world (Bash and Cohen 2013). In 2014, a British court ruled that electronic mass surveillance under programs like PRISM were legal and had enough safeguards to protect individuals’ online privacy (Scott 2014).

Websites routinely track your personal information and online activities (Nguyen 2011). Websites and online applications use cookies to track information about users. Cookies allow website operators to see your browsing history, store your log-in information, and help personalize sites by remembering your preferences and searches from previous visits. Though many Internet users have learned how to disable cookies through control panels, most Internet users do not do so. Facebook and other social media networks also maintain and track personal data about their users, including where the users live and users’ personal interests and activities. Many Facebook applications (including Zynga, the creator of the online game FarmVille) were transmitting Facebook user IDs to advertisers and Internet tracking firms. Facebook and Zynga both pledge not to share personally identifiable information with third parties (Nguyen 2011).

Google’s and Facebook’s privacy policies have been scrutinized by media watch groups, politicians, and consumers. In 2011, Facebook settled FTC charges that it deceived users by telling them that it would keep their Facebook information private, though it was sharing users’ personal data with others. According to its settlement, Facebook must not make any deceptive privacy claims, is required to get consumers’ approval before making changes in data sharing, and is required to obtain assessments of its privacy practices by independent, third-party auditors through 2031 (FTC 2011). In 2012, Google announced plans to unify data collections across all its services, including its search engine, YouTube, and Gmail. Consumer privacy groups expressed concern that the data consolidation would reveal information about a person’s location, religion, sexual orientation, health status, and personal interests. Google claims that it maintains a priority on user security, transparency, and control.

What Corporations Know

In Focus

The Boundary-less Workplace

Wendy Boswell and Julie Olson-Buchanan (2007) describe how communication technology (CT) has changed the media we use to communicate with each other in the workplace, but also how it has significantly changed our connection to work. CT allows for greater flexibility in managing one’s work, but it may give employees little opportunity to disengage from work. We don’t think much about responding to a voice message after dinner or checking e-mail messages while on vacation. Though employees may not be officially on the job, CT has “enabled an anytime-anywhere connectedness of employees to their work” (Fenner and Renn 2004:184).

Teresa Sullivan (2014) cautions against the merging of work versus non-work time. Referring to Lewis Coser’s (1974) concept of greedy institutions, she highlights how different institutions compete for the limited energies and time commitments of individuals. The workplace has become our primary greedy institution via CT. “Continuous connectivity allows employers to reach into the after hours of their employees’ lives, extending the workday beyond its traditional limits. And globalization, which extends a firm’s reach across many time zones, requires more workers to be alert and responsive for more hours of the day” (Sullivan 2014:4).

CT use during non-work time has been positively correlated to an employee’s workload and career ambitions. Remaining connected is viewed as a convenient means to keep up with one’s work and as a way to get ahead in one’s organization or occupation (Boswell and Olson-Buchanan 2007). This high level of connectivity could be described as an expectation of our work. At the same time, CT use during non-working hours has been linked to higher employee stress levels, job burnout, and lower job satisfaction (Fonner and Roloff 2010; Leonardi, Treem, and Jackson 2010). In their 2014 study, Kevin Wright and his colleagues discovered that as the number of outside-of-work hours increased via CT, perceptions of work versus life conflict increased. Individuals noted how their personal life suffered or their personal needs were neglected because of checking in on their work online.

In 2014, Daimler, the German automobile corporation, announced that their employees can take advantage of a Mail on Holiday program. The program automatically deletes all incoming email while an employee is on vacation. The sender is notified that the email has not been received and then is asked to contact a substitute. How does this program alter expectations of the employee?

The Digital Haves and Have-Nots

The term digital divide was first used in the mid-1990s by policy leaders and social scientists concerned about the emerging split between those with and those without access to computers and the Internet. The term refers to the gap separating individuals who have access to new forms of technology from those who do not. In addition, others have identified a gap between those who can effectively use new information and communication tools and those who cannot (Gunkel 2003). Despite the increasing diffusion of computers and an overall increase in Internet use, a deep divide remains “between those who possess the resources, education and skills to reap the benefits from the technology and those who do not” (Servon 2002:4). President Obama has pledged to make high-speed Internet service available to most Americans, raising access to 90% in the coming decade.

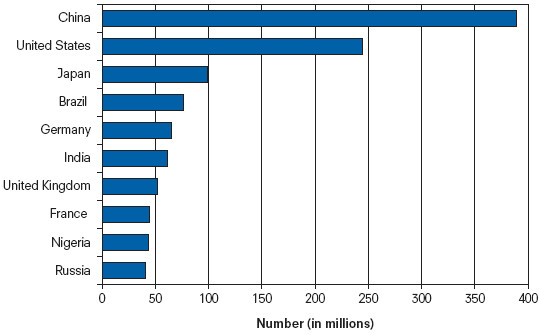

The divide is also a global phenomenon. Less than 10% of the world’s population uses the Internet (Guillén and Suárez 2005). According to data collected by the Central Intelligence Agency (2012), China and the United States rank the highest with Internet users—each has more than 200 million users (refer to Figure 11.1). Developing non-Western countries such as those in Africa, South America, and South Asia have fewer than a million Internet users.

The Internet has been described as both empowering and discriminating, enabling residents in some countries to pursue a better life while others are left behind (Guillén and Suárez 2005). Cross-national research has linked the diffusion of Internet technology with developed service sector economies, an educated population, economic development, and significant research and development investment. Users in less-developed countries have basic access problems: economic (cost of basic necessities vs. cost of Internet access), technological (varying ability of local networks), and geographical (limited access outside urban areas) aspects (Vartanova 2002). Mainly because of income differentials, the Internet is beyond the reach of global citizens. For example, in countries with low human development, the average annual income is about $1,200 (in U.S. dollars); the cost of owning a cheap personal computer would take more than half of that income, about $700 (Drori 2004; United Nations Development Programme 2001). On the other hand, pay-as-you-go plans have made cellular phones more affordable. Nearly 40% of all adults living in poverty are cellular-only users compared with 21% of adults with higher incomes (Blumberg et al. 2011). Some states also provide cellular phone subsidies for low-income residents.

The digital divide implies a chain of causality. Access and ability to use computers and Internet technology help improve one’s social and economic well-being; lack of access to computers and the Internet harms one’s life chances. But it is also true that those who are already marginalized in society will have fewer opportunities to access and use computers and the Internet (Warschauer 2003). Among persons with incomes of $30,000 or less, only 52% have broadband access compared with 91% of individuals with incomes more than $75,000. Data also indicate that rates of broadband usage are higher among individuals with a bachelor’s degree or more (90%) than among those with a high school degree (58%) (Pew Research Internet Project 2013). The U.S. Census Bureau (2010) projected that the average consumer would spend almost $1,000 for media usage (e.g., television, Internet, cell phone, and radio) in 2010. In contrast, in 2004, the average consumer spent $770.

The digital divide is a symptom of a larger social problem in the United States: social inequality based on income, educational attainment, and ethnicity/race. Data from the Pew Internet & American Life Project (2012) reveal how Internet use is divided along demographic and socioeconomic lines. Internet use is higher among Whites and Blacks than among Hispanics. Higher Internet use is positively associated with higher incomes and educational attainment. (Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for more information about the digital divide.) However, as digital access has improved, researchers have noted an overall increase in the use of media for time wasting among youth and continuing disparities. As reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation (Rideout, Foehr, and Roberts 2010), youth whose parents attained a high school degree or less spend more time per day exposed to media (television, music, video games, and movies) than youth whose parents have a college degree.

Internet access is not the only issue facing underserved communities. Wendy Lazarus and Francisco Mora (2000) identified four online content barriers. The greatest barrier is the lack of locally relevant information. They discovered that low-income users seek practical and relevant information that affects their daily lives, on topics such as education (adult high school degree programs), family (low-cost child care), finances (news on public benefits, consumer information), health (local clinics, low-cost insurance resources), and personal enrichment (foreign-language newspapers). In some instances, information may be available in printed documents, but these may be difficult to locate or obtain. General information may exist online, but it might not be suitable to low-income audiences. For example, online housing services might list high-end rental units rather than lower-rent housing.

The second barrier identified by Lazarus and Mora (2000) was the lack of information at a basic literacy level. According to the authors, a number of online tutorials that review computer program and Internet skills are written at a higher level of literacy. The third barrier was the need for content for non-English speakers. There is little government material (e.g., on voting, Medicare, or taxes) translated into Spanish. Last, there is a need for more websites that reflect diverse cultural heritages and practices.

Social Media’s Growing Influence

Reducing the Digital Divide

Exploring social problems

Internet Access

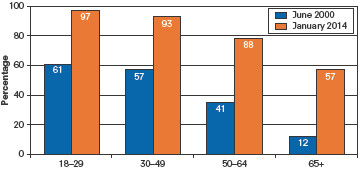

Figure 11.2 Internet use by age, 2000 and 2014 (percentage of adults age 18+ reported)

SOURCE: Fox and Rainie 2014.

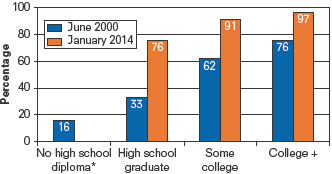

Figure 11.3 Internet use by educational attainment, 2000 and 2014 (percentage of adults age 18+ reported)

SOURCE: Fox and Rainie 2014.

NOTE: For 2014, high school graduate and no high school diploma categories were combined.

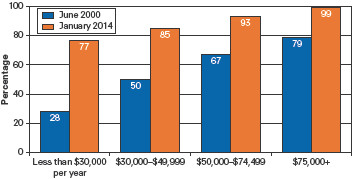

Figure 11.4 Internet use by income level, 2000 and 2014 (percentage of adults age 18+ reported)

SOURCE: Fox and Rainie 2014.

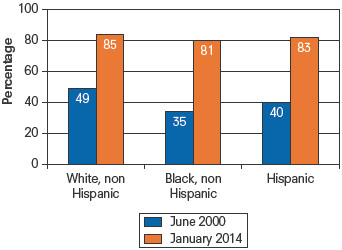

Figure 11.5 Internet use by race, 2000 and 2014 (percentage of adults age 18+ reported)

SOURCE: Fox and Rainie 2014.

What Do You Think?

In 1995, only 14% of U.S. adults had Internet access, mostly through dial-up modem connections, according to the Pew Research Center. Forty-two percent had never heard of the Internet. Two decades later, 87% of U.S. adults use the Internet for either work or personal use (Fox and Rainie 2014).

Figures 11.2 through 11.5 present 2000 and 2014 U.S. data on Internet use based on four demographic variables—age, education, income, and race.

How would you describe the change in Internet use between the two reported years? Which demographic characteristic has had the most increase in level of use?

Fifty-three percent of Internet users say it would be very hard to give up the Internet (Fox and Rainie 2014). Could you give up Internet access in some or all parts of your life?

The Death of the Newspaper?

As the fourth estate, journalism serves as a watchdog for government activities. Independent reporters, especially through print media, keep the public informed about political issues and activities. According to Robert McChesney and John Nichols (2010), citizens should have “media that regard the state secret as an assault to popular governance, that watch the politically and economically powerful with a suspicious eye, that recognize as their duty the informing and enlightening of citizens” (p. 2).

Yet, in our increasingly digital age, newspaper readership has declined while the use of online news sources has increased. In 2010, 37% of Americans said they read a paper yesterday (compared with 43% in 2006), while the number who said they read news online yesterday was 34% (compared with 29% in 2006) (Project for Excellence in Journalism 2011).

This transition has caused concern among those in the newspaper industry: owners and employees. According to the Newspaper Association of America (2012), in 2000, there were 1,468 daily papers. By 2011, the number of daily papers had declined to 1,382. Nearly every large paper has fewer pages and fewer articles; some have eliminated entire sections (Pérez-Peña 2009). In 2012, 2,600 full-time newsroom jobs were cut. While some argue that news is more accessible via the Internet, the quality and content of the news is changing. According to the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism (2012), the decline in print newspapers will mean “less coverage of government in suburbs or remote cities, pulling back on state government coverage, the decimation of specialty beats like science or religion, fewer feature stories and elimination of many weekday feature sections.”

So what will take the place of your local newspaper? Several online companies have created hyperlocal news sites that allow readers to create their own neighborhood-focused news site—with stories, information, and advertising catering to their specific interests and needs. But some think that online news services are not the same. In a 2009 Senate hearing on journalism, Senator Benjamin Cardin (D-MD) testified, “As local newspapers disappear, we lose an important check on local governments, state governments, the federal government, elected officials, corporations, school districts, businesses, individuals and more. Newspapers and the investigative journalism they provide are essential in a free, democratic society and must be preserved” (quoted in Tucker 2009:8). According to Gary Kebbel, journalism program director for the Knight Foundation, the news business “is in a difficult time period right now, between what was and what will be” (quoted in Miller and Stone 2009:B1).

Newspaper Readership Then, Now and in the Future

Driving Distracted

In 2007, a 53-year-old male driver was checking his e-mail while driving and caused a five-car pileup on Interstate 5 outside of Seattle, Washington. Driving while texting (DWT) is part of the growing phenomenon of distracted driving. Texting, along with the use of cell phones while driving, has been attributed to at least 1.3 million traffic accidents. Cell phone use causes more crashes than texting—1.3 million versus 200,000. According to the National Safety Council (2010), 28% of all traffic accidents involve talking and texting on cell phones. Drivers who use a cell phone—handheld or hands-free—are four times more likely to be involved in an accident.

The Seattle incident led to the passage of two laws, the first of their kind in the nation. One law prohibits driving while texting, and the second prohibits the use of a handheld phone while driving. Both laws are secondary enforcement laws, which means a driver will be ticketed for the offense only if pulled over for another driving violation. Public support for laws banning cell phone use while driving is gaining momentum (National Safety Council 2010). Since 2009, 44 states have enacted bans on texting while driving, and 38 states have enacted total cell phone bans for young drivers. Fourteen states ban the use of handheld devices while driving (Governors Highway Safety Association 2014).

Texting, along with the general use of cell phones while driving, has been attributed to at least 1.3 million traffic accidents.

© sshepard/iStock

In an executive order signed by President Obama, federal employees are not allowed to text while driving. The federal government also plans to ban texting by interstate bus drivers and truckers. The use of cell phones may be limited to emergency situations.

Do You Trust the News Media?

Whether we are watching CNN, ABC, NBC, CBS, or Fox, we rely on reporters for most if not all our information about our community and our world. According to the Project for Excellence in Journalism (2004), public attitudes about the press have been growing less positive for about 20 years. In its report, The State of the News Media 2004, the Project for Excellence in Journalism identified the disconnection between the public and the news media over motive as the fundamental reason for the decline in public support. Whereas journalists believe they are working in the public interest, the public believes that news organizations are working primarily for profit and that journalists are motivated by professional ambition. In 2011, reporters from the News of the World, a tabloid newspaper in Great Britain, were exposed for phone hacking practices used to gather information about celebrities, politicians, and other people in the news.

The public debate about whether U.S. media are liberal or conservative also sensitizes the public to how the media could be manipulative or subjective in content. In addition, people are increasingly distrustful of the large multinational corporations that own and control most of the news media (Project for Excellence in Journalism 2004). These findings are confirmed by the Pew Research Center (2011). Eighty percent of the public feel that news organizations are influenced by powerful people and organizations rather than being independent. Approximately 60% of Americans consider news organizations politically biased. In addition, more than 75% believe news organizations tend to favor one side rather than treat all sides fairly.

In addition, the Pew Research Center examined how Americans regard their news organizations over time. In 1985, 55% of those surveyed felt that the news media usually get their facts straight, while 34% believed that news organizations usually provide inaccurate reports. In 2011, the percentages have switched: 25% of those surveyed felt that the news media get the facts straight and 66% believed their stories are often inaccurate (Pew Research Center 2011). The 2011 survey found that most Americans prefer news with no political viewpoint.

During the early months of the 2008 presidential campaign, a news report claimed that Democratic candidate Senator Barack Obama had attended a madrassa (a Muslim religious school) while living in Indonesia. The allegation was first raised in Insight, a conservative Internet magazine owned by the Washington Times, and it was repeated by other news services. The magazine alleged that Obama had been raised as a Muslim and that the sources of its information were researchers close to rival Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton’s campaign. The deputy headmaster of the school Obama attended stated that the school is a public one that does not focus on religion. Obama’s campaign staff maintained that the story was “completely ludicrous” and identified the candidate as a committed Christian. Clinton’s staff claimed that they had nothing to do with the story.

Community, Policy, and Social Action

Federal Communications Commission and the Telecommunications Act of 1996

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was established by the Communications Act of 1934 and is charged with regulating interstate and international communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable. As an independent agency, the FCC oversees violations of federal law and policies and reports directly to the U.S. Congress (FCC 2004). Under current FCC rules, radio stations and broadcast television channels cannot air indecent language or material that shows or describes sexual or excretory functions between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m., when children may be watching. In response to a violation, the FCC may issue a warning, revoke a station’s license, or impose a monetary fine. In the entire history of the FCC, the commission has fined two television stations for indecency (K. Kelly, Clark, and Kulman 2004).

Introduced a week before the Super Bowl in 2004, the Broadcast Decency Enforcement Act was designed to amend the Communications Act of 1934. The bipartisan bill increased penalties to $500,000 for violating FCC regulations. Broadcasters could also lose their license if they violated indecency standards three times. The act would not apply to cable television programming. In the case of the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show, each CBS station that aired the program could have been fined as much as $27,500. After the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show (and Janet Jackson’s wardrobe malfunction), television broadcasters began to police their programming more closely.

Through the FCC, the public can file complaints on a range of issues: billing disputes, wireless questions, telephone company advertising practices, telephone slamming (switching a consumer’s telephone service without permission), unsolicited telephone marketing calls, and indecency and obscenity complaints. Along with the FTC, the FCC is enforcing the National Do Not Call Registry, which went into effect in October 2002. The FCC and FTC report that more than 55 million people have signed up for the registry.

The first major overhaul of the original 1934 act, the Telecommunications Act of 1996, was seen as a way to encourage competition in the communications industry. The law specified how local telephone carriers may compete, how and under what circumstances local exchange carriers can provide long-distance services, and ways to deregulate cable television rates. Also included in the act were provisions to make telecommunications more accessible to disabled Americans. A Decency Act makes it a crime to knowingly convey pornography over the Internet on a website accessible to children.

Although the act was presented as an opportunity to encourage competition and break down media monopolies, industry watchers noted that the 1996 law swept away the minimal consumer and diversity protections of the original 1934 act. The 1996 act reduced competition and allowed more cooperation between media giants. Data we reviewed in an earlier section of this chapter seem to support this. The new law permitted some of the largest industries—those not active in creating media content, such as telephone companies—to enter the television, radio, and cable industry. New industries joined older media companies to form interlocking partnerships, rather than become independent competitors as the act had predicted. For example, U.S. West, one of the largest telephone companies in the country, acquired Continental Cablevision, the third-largest cable system. Sprint, the long-distance telephone company, formed a joint venture with TCI, a cable company. The merger between Disney, ABC Broadcasting, and Capital Cities was made possible only through the passage of the 1996 law (Bagdikian 1997).

Who Is Watching the Media?

Numerous organizations have emerged as watch groups monitoring media accuracy and content. Groups such as Accuracy in Media (AIM) and the Center for Media and Public Affairs (CMPA) are nonprofit, grassroots organizations that attempt to expose biased and inaccurate news coverage while encouraging members of the media to report the news fairly and objectively. AIM publishes a newsletter and weekly newspaper column, broadcasts a daily radio commentary, and promotes a speaker’s bureau to expose faulty reporting. On its website, current news stories are posted, along with AIM’s analysis of the story’s accuracy. CMPA conducts scientific research of the news and entertainment events, such as coverage of the presidential elections, the current presidential administration, international media, science and health, and religion (Center for Media and Public Affairs 2012).

Several organizations attempt to improve and protect the integrity of journalists in print, electronic, and Internet media. The Project for Excellence in Journalism (2004) began as an initiative by journalists to clarify and raise the standards of American journalism. The project serves as a research organization, conducting an annual review of local television news, producing a series of content studies on press performance, and offering educational programs for journalists. The project also provides information to the public about what to expect from the press, how to write a letter to the editor, and how to talk to the news media. Another organization, the Committee to Protect Journalists, is an independent, nonprofit organization promoting press freedom worldwide by defending the rights of journalists to report the news without fear of reprisal. The organization documents attacks on the press worldwide, including the number of journalists killed, missing, or imprisoned. For 2014, the committee reported that 60 journalists were killed; international journalists covering conflict and dangerous situations in the Middle East, Ukraine, and Afghanistan were at higher risk (Committee to Protect Journalists 2014).

Voices in the Community

Geena Davis

Responding to the lack of female characters in television and motion picture programming, Geena Davis founded the See Jane program to promote and advance gender balance in media for children 11 years of age or younger. Davis (2006) explains that after she gave birth to her daughter and began to watch preschool programs, she did a study of her own, examining the characters in her daughter’s videos, and she realized that the programs were dominated by male characters. The See Jane program was renamed the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media.

Where the Girls Aren’t was the first research project sponsored by the program, using content analysis to examine 101 top-grossing G-rated animated and live action films from 1990 to 2004 (Kelly and Smith 2006). In these films, researcher Stacy Smith found that there were three male characters for every one female character. Twenty-three percent of speaking characters were female, and more than 80% of film narrators were male. This gender imbalance can affect children’s gender development, reinforcing children’s stereotypical attitudes and beliefs about gender. According to Davis, “by making it common for our youngest children to see everywhere a balance of active and complex male and female characters, girls and boys will grow up to empathize with and care more about each other’s stories” (quoted in Kelly and Smith 2006:9–10).

In the institute’s 2014 study, Stacy Smith, Marc Choueiti, and Katherine Pieper examined female characters in the most popular films released between January 2010 and May 2013 in 11 countries. Their study confirms the continuing absence of women and girls on screen. Based on a total of 5,799 speaking or named characters on screen, only 31% were female, a gender ratio of 2.24 males to every one female. Only 23.3% of the films had a girl or woman as the lead or co-lead in the story. When females were shown, they were more than two times likely to be shown in sexually revealing clothing (24.8% vs. 9.4%), thin (38.5% vs. 15.7%), or partially or fully naked (24.2% vs. 11.5%) than males (Smith, Choueiti, and Pieper 2014). Smith and her colleagues highlight the important relationship between filmmaker gender and character gender—films with at least one female director or writer have a higher percentage of girls/women on the screen than those without—and conclude that the industry needs more female directors and writers to improve the number of female lead characters.

Geena Davis visits a class of second graders to promote lessons on gender stereotypes in the media. Davis leads the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, advocating for more girls and women in television and films, in front of and behind the camera.

Splash News/Newscom

Certainly Davis’s experience on the film Thelma and Louise helped her recognize the impact of a strong female character on women and men. She acknowledges the effect of media images on adults, but her concern is on the impact on children. “We know that kids learn their value by seeing themselves reflected in the culture. They say, ‘I see myself! I must matter. I must count.’” Her goal is for media portrayals to be “normal and natural for children to see worlds and characters—be they Martians or dinosaurs or talking toaster ovens—that are roughly half female and male. Just like the real world that our kids live in” (Davis 2006).

In addition to ongoing research, the institute continues to educate parents and child professionals about the importance of gender equity in the media. The program’s goal is to see females constituting half of all characters in media made for young children.

Media Literacy and Digital Literacy

There are ongoing efforts among scholars, policy makers, and educators to promote media literacy, the ability to understand, analyze, and critique media content. It is about shifting from the role of a passive receiver of media to an active critical receiver and includes asking several questions: For whom is this media message intended? Who wants to reach this audience, and why? From whose perspective is this story being told? Whose voices are being heard, and whose are absent? (Media Awareness Network 2004). This type of literacy develops one’s abilities to examine the social and commercial context of media messages as well as the consequences of those messages (Considine, Horton, and Moorman 2009). Media literacy is important for the development of democracy and active citizenship, lifelong learning, and economic and labor competitiveness (Livingston, Van Couvering, and Thumin 2004).

Recently, the definition of literacy has expanded to include digital media. Digital literacy refers to an individual’s ability to appropriately use digital tools and skills to identify, manage, evaluate, analyze, and synthesize digital sources; to construct new knowledge; and to communicate with others (Martin 2006). Elizabeth Thoman and Tessa Jolls (2004) observed how “teens today have no memory of life without television; kindergarteners know only a world with cell phones, laptops, instant messaging, and movies on DVD. To ignore the media-rich environment they bring with them to school is to shortchange them for life.”

Since 2007, the European Commission has promoted a set of guiding principles and initiatives promoting media literacy, with a focus on digital media and technology, claiming,

The rapid rise of digital technology and its increasing use in business, education and cultural activities has offered new challenges as well as new opportunities. With the nature of media changing and the volume of information increasing, it is important to ensure that individuals have the necessary skills to be able to use and make informed decisions about media and digital technologies. (European Commission 2014)

There is no U.S. federal initiative regarding media literacy.

Media Effects

Sociology at Work

Software Development

Jenny Grinblo – Class of 2011

Undergraduate Major: Sociology

Undergraduate Minor: Global Citizenship

Software developers write the hidden codes for your word processing program or for your favorite app on your phone. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014) describes software developers as the “creative minds” behind computer programming. To enter this occupational field, you will need a bachelor’s degree, usually in a related area like Computer Science. You should also have strong computer programming skills. There are two types of software developers: applications software developers, who design computer applications such as games, and systems software developers, who create operating systems for computers (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014).

Since graduating in 2011, Sociology alum Jenny Grinblo has worked in a mobile app agency in London, where she leads the User Experience and Design Team. She describes her job as an intersection of her internship (as a graphic designer in a local theatre) and her Sociology degree. Jenny helps “build digital products which balance client business needs and end-user needs well, and are useful, easy to use, and provide a positive experience.”

A large part of my work is being able to ignite empathy among our team and clients, so that they can “walk in the shoes” of our apps’ end users. I frequently employ ethnographic interviewing, surveys, and do the equivalent of literature reviews of relevant resources. I’ve also given talks and run workshops to teach people how to employ qualitative research methods in order to uncover people’s needs and find patterns in individual stories.

Jenny received the majority of her career advice from networking (in person and via Twitter) and online resources (job postings, LinkedIn, and blogs). To current majors considering their future employment, Jenny says,

I would advise Sociology majors to look beyond their immediate academic activities and make a list of the skills and interests they possess, for example: writing, understanding people, gathering a lot of information and making sense of it, etc., and look for intersections between those interests and skills, rather than trying to apply a portion of them due to a perceived lack of options. I was lucky to meet a mentor who suggested that the combination of my skills could be applied in the User Experience field, but there might be other fields out there that can allow Sociology majors to build on their core skills and interests in a similar way.

Chapter Review

- 11.1 Define media

Media are the technological processes facilitating communication between a sender and a receiver.

- 11.2 Explain how the different sociological perspectives examine social problems related to the media

Functionalists examine the structural relationship between the media and other social institutions that affect content, including the social and economic conditions of American life and society’s beliefs about the nature of men, women, and society. Conflict theorists believe that the media can be fully understood only when we learn who controls them. The media frame messages in a way that supports the ruling elite and limits the variety of messages that we read, see, and hear. Feminist theorists attempt to understand how the media represent and devalue women and minorities. They examine how the media either use stereotypes disparaging women and minorities or completely exclude them. The interactionist perspective focuses on the symbols and messages of the media and how the media come to define our social reality.

- 11.3 Review the importance of the digital divide

The term digital divide refers to the gap separating individuals who have access to and understanding of new forms of technology from those who do not. This divide is a symptom of a larger social problem: social inequality based on income, educational attainment, and ethnicity/race.

- 11.4 Explain the relationship between media technology and a boundary-less workplace

E-mail and smartphones may help employees manage their work better, but these technologies also give employees little opportunity to disengage from their work. Their work becomes boundary-less as their work continues online or on the phone after work hours or at home.

- 11.5 Identify the importance of media literacy

Evidence shows that media education can help mitigate the harmful effects of the media. Parents can provide the most effective intervention to reduce the effects of media violence on children, and school-based intervention also seems to help. The goal is media literacy, shifting the viewer from the role of passive receiver to that of active critical receiver.

Key Terms

- digital divide, 311

- digital literacy, 321

- impression management, 309

- media, 300

- media literacy, 321

- social media, 302

Study Questions

- Explain how the media serve to unite and divide members of society.

- How is control over the content of the media (according to conflict and feminist perspectives) problematic? What groups are in conflict?

- From an interactionist perspective, examine how Michael Jackson’s death met the three criteria for newsworthiness.

- How is one’s access to media and technology related to one’s life chances?

- Which sociological perspective could best explain how trust is earned by new agencies and outlets? Do you trust the news media? Why or why not?

- Define what is meant by media literacy. How does media literacy mitigate the harmful effects of the media?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.