Chapter 10 Health and Medicine

Learning Objectives

- 10.1 Describe the social determinants of health

- 10.2 Explain the three measures of epidemiology

- 10.3 Describe how the different sociological perspectives address problems related to health and medicine

- 10.4 Identify the relationship between education and health

- 10.5 Summarize the different models of health care in the United States

If you are thinking that this is going to be a discussion about human physiology and theories about germs and viruses, full of medical terms, you’re wrong. Although medicine can identify the biological pathways to disease (Wilkinson 1996), we will need a sociological perspective to address the social determinants of health. “Health is a result of an individual’s genetic makeup, income and educational status, health behaviors, communities in which the individual lives, and the environments to which he or she is exposed” (Lurie and Dubowitz 2007: 1119). To better understand the connection between our social structure and health, we must investigate how our political economy, our corporate structure, and the distribution of resources and power influence health and illness (Conrad 2001a).

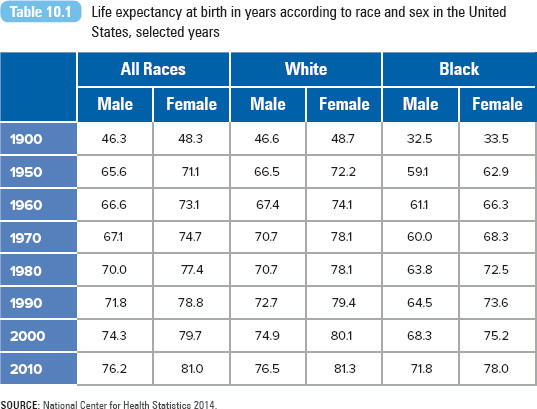

Consider the gross inequalities in health between and within countries. Life expectancy at birth is highest for a child born in Japan (81.9 years) and lowest for one born in Sierra Leone (34 years). Within the United States, there is a 20-year gap in life expectancy between the most and least advantaged populations (Marmot 2005). There is no biological reason why life expectancy should be 48 years longer in Japan than in Sierra Leone or why there is a gap in life expectancy between the rich and the poor in the United States. In Health, United States, 2013 (National Center for Health Statistics 2014), the CDC reported that life expectancy had reached 78.7 years (see Table 10.1). Although Americans are living longer, life expectancy gains have lagged behind other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2013).

When two U.S. aid workers contracted the Ebola virus while working in West Africa in 2014, they were flown back to the states and treated with an experimental drug. There is no vaccine for this hemorrhagic virus. News of the experimental and special treatment of the doctor and nurse raised criticism, most notably why ZMapp was not made available in West Africa but was made available in the United States to two White aid workers. As of the end of 2014, Ebola had infected 15,145 people and killed 5,420 in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria. Between 60% and 90% of those infected had died from the disease. The aid workers were declared fully recovered, though it is unclear whether the drug, ZMapp, contributed to their recovery.

Finally, consider how politics and the law serve as agents of health system change. Before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (also referred to as the Affordable Care Act, ACA, or Obamacare), 44 million Americans did not have health insurance. President Barack Obama said he was signing the bill on behalf of his mother, along with others who struggled to find affordable and comprehensive health coverage. The signing of the bill enshrined “the core principle that everybody should have some basic security when it comes to their health care” (Obama 2010). Under the law, health insurance coverage was expanded through private insurance or Medicare or Medicaid plans.

Sociological Perspectives on Health, Illness, and Medicine

The sociology of health and illness includes the field of epidemiology. Epidemiology is the study of the patterns in the distribution and frequency of sickness, injury, and death and the social factors that shape them. Epidemiologists are like detectives, investigating how and why groups of individuals become sick or injured (Cockerman and Glasser 2001). They don’t focus on individuals; rather, epidemiologists focus on communities and populations, addressing how health and illness experiences are based on social factors such as gender, age, race, social class, or behavior (Cockerman and Glasser 2001). Epidemiology has successfully increased public awareness about the risk factors associated with disease and illness, leading many to quit smoking, to participate in more physical exercise, and to eat healthier diets (Link and Phelan 2001).

For example, type 2 diabetes, the most common form of the disease, occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin or when the cells ignore the insulin. An estimated 25.8 million Americans have type 2 diabetes (diagnosed or undiagnosed). However, the disease can be effectively managed with healthy behaviors such as meal planning, exercise, and weight management (American Diabetes Association 2012). Modernization, fast foods, and physical inactivity have led to significant increases in the number of type 2 diabetes cases in countries such as Brazil and India. Indian public health officials estimate that by 2035 there will be 109 million diabetic patients ages 20 to 79 (Lipska 2014). A disease that usually affects the old is affecting the younger Indian population, primarily because they have adopted a modern lifestyle and diet (Kleinfield 2006). Similar dire predictions are made for China; by 2035 it is expected that there will be 142.7 million Chinese with diabetes (Lipska 2014).

Epidemiologists use three primary measures of health status: fertility, mortality, and morbidity. These data are routinely collected by the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. Fertility is the level of childbearing for an individual or a population. The basic measure of fertility is the crude birthrate, the number of live births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 in a population. The U.S. crude birthrate for 2012 was 12.6 births per 1,000 women (Martin et al. 2013). Related to this is the measure of fecundity, the maximum number of children that could be born (based on the number of women of childbearing age in the population).

In the early 1900s, a woman could expect to give birth to about four children, whereas a woman during the Great Depression of the 1930s could expect to have only two (U.S. Census Bureau 2002). The lowest number of births per woman was 1.8 children in the mid-1970s. Since then, the rate has averaged around two births per woman. Fertility is determined by a set of biological factors, such as the health and nutrition of childbearing women. But innovations in medicine, in the form of infertility treatments, have also made childbirth possible for women who once considered it impossible. Social factors, such as our social values and definitions of the role of women, the ideal family size, and the timing of childbirth, can influence fertility. Fertility rates have also been determined by the ethnic and foreign-born composition of the population. Demographer Kenneth Johnson explains, “You could shut off immigration tomorrow and the impact of the foreign born on U.S. demographic trends would still be a powerful force” (quoted in Roberts 2010:A13). Hispanics are not only the largest minority group in the United States but also the youngest. One in four newborns is Hispanic (Pew Hispanic Center 2009).

Mortality is the incidence of death in a population. The basic measure of mortality is the crude death rate, the number of deaths per 100,000 people in a population in a given year. For 2011, the U.S. death rate was 807.3 deaths per 100,000 people (Hoyert and Xu 2012). In the United States, it is unlikely that we’ll die from acute infectious diseases, such as an intestinal infection or measles. Rather, the leading causes of death are chronic conditions such as coronary heart disease, cancer, stroke, and chronic lower respiratory disease, all of which have been linked to heredity, diet, stress, and exercise. The leading causes of death vary considerably by age. The leading cause of death of college-age Americans is unintentional injuries, followed by homicide and suicide. Among the elderly, mortality caused by chronic diseases (heart disease, cancer, chronic bronchitis, diabetes) is more prevalent.

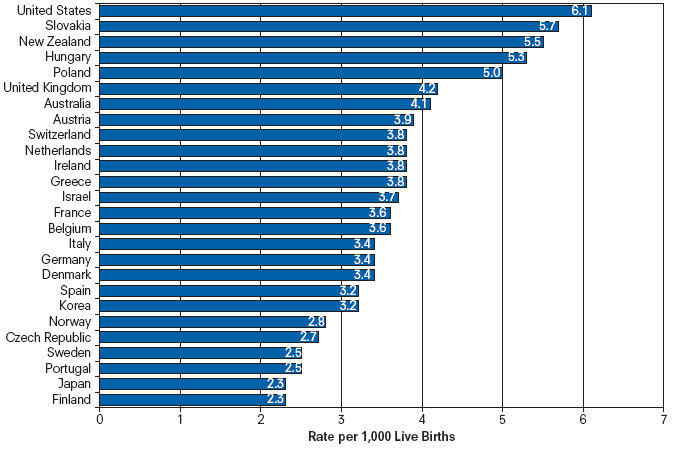

Infant mortality is the rate of infant death per 1,000 live births. For 2010, the infant mortality rate was 6.1 deaths per 1,000 live births (MacDorman et al. 2014). The three leading causes of death among U.S. infants were congenital birth defects, low birth weight, and sudden infant death syndrome. Infant mortality is considered a basic indicator of the well-being of a population, reflecting the social, economic, health, and environmental conditions in which children and their mothers live. Though infant mortality rates in the United States have declined, rates are disproportionately higher for minority children. In 2010, the highest rate, 11.61 deaths per 1,000 live births, for infants of non-Hispanic Black mothers, was more than double the death rate of infants born to White mothers (5.19) (Murphy, Xu, and Kochanek 2012).

The infant mortality rate is historically higher in the U.S. than in other developed countries. (Refer to Figure 10.1 for a comparison of 2010 infant mortality rates.) When comparing U.S. infant mortality rates with the rates of other countries, researchers note that maternal health care is more widely and uniformly available in countries with national health care programs (UNICEF 2012).

Figure 10.1 Infant mortality rates: Selected Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Countries, 2010

SOURCE: MacDorman et al. 2014.

Morbidity is the study of illnesses and disease. Illness refers to the social experience and consequences of having a disease, whereas disease refers to a biological or physiological problem that affects the human body (Weitz 2001). Epidemiologists track the incidence rate, the number of new cases within a population during a specific period, along with the prevalence rate, the total number of cases involving a specific health problem during a specific period (Weitz 2001). For example, the 2013 incidence rate for diabetes was 1.7 million people age 20 years or older; the prevalence rate was 29.1 million or 9.3% of the population (American Diabetes Association 2014). Incidence rates help measure the spread of acute illnesses, which strike suddenly and disappear quickly, such as chicken pox or the flu. The prevalence rate measures the frequency of long-term or chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, asthma, or HIV (Weitz 2001). The National Center for Health Statistics publishes the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, a weekly summary of surveillance information on reported diseases and deaths.

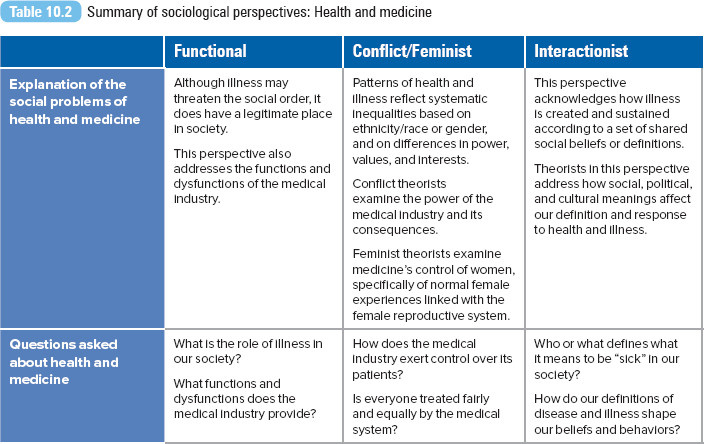

In addition to epidemiological analyses, sociologists have applied theoretical perspectives to better explain the social problems of health and illness.

Functionalist Perspective

Émile Durkheim conducted the first empirical analysis of suicide in the late 1800s. Before Durkheim’s work, scientists attributed suicide primarily to psychological or individual factors. However, Durkheim treated suicide as a social fact and identified the relationship between suicide and the level of social attachment or regulation between an individual and society. His research is the first true epidemiological analysis, and, most important, it revealed the relationship between illness and the larger social structure. The stability of society is paramount from a functionalist’s perspective. Consider for a moment what happens when you become sick. When are you sick enough not to attend class? How do others begin to treat you? According to the functionalist perspective, illness has a legitimate place in society. The first sociological theory of illness was offered by Talcott Parsons (1951); the theory addresses how individuals are expected to act and to be treated while sick (Weitz 2001), a set of rights and responsibilities condoned by society (Barclay 2012). This set of behaviors is part of Parsons’s theory of the sick role.

The sick role has four parts. In the first, sick people are excused from fulfilling their normal social role. Illness allows them to be excused from work, from chores around the house, or even from attending class! Second, sick people are not held responsible for the illness. The flu that’s going around is no one’s fault, so you aren’t personally blamed if you catch it (although your roommates may blame you if they catch what you have). Third, sick people must try to get well. Illness is considered a temporary condition, and sick people are expected to take care of themselves with appropriate measures. In relation to this, Parsons offers the last part, that sick people are expected to visit medical authorities and to follow their advice.

Although Parsons legitimized the social role of illness, he also identified a critical source of the problem in health care today. In the fourth element, Parsons identified the authority and control of the physician. Even though you’re the one who is sick, the doctor has the ultimate power to diagnose your condition and to tell you that you’re “really” sick.

Doctors play a prominent role in managing our illnesses, but they don’t do it alone. Doctors, along with nurses, pharmaceutical corporations, hospitals, and health insurers, form a powerful medical industry. The medical industry has served us well with its technological and scientific advances, offering a wider array of medical services and treatment options. However, this industry has also created a set of problems, or dysfunctions, as functionalists like to refer to them. Medicine has shifted from a general practitioner model (a family doctor who took care of all your needs) to a specialist model (where one doctor treats you for a specific ailment). You are receiving quality care, but at a price (and you are paying to be treated by many different doctors, instead of just one). As a result, health care costs have become less affordable, leaving many without adequate coverage and care. The system intended to heal us does not treat everyone fairly. We will explore this further in the next perspective.

Population Clock

Population Growth and Health Care

Conflict Perspective

According to conflict theorists, patterns of health and illness are not accidental or solely the result of an individual’s actions. Conflict theorists identify how these patterns are related to systematic inequalities based on ethnicity/race or gender and on differences in power, values, and interests.

Conflict theorists may take a traditional Marxist position and argue that our medical industry is based on a capitalist system, founded not on the value of human life, but on a pure profit motive. A conflict theorist argues that instead of defining health care as a right, our capitalistic system treats health care as a valuable commodity dispensed to the highest bidder. Studies consistently find that those in upper social classes have better health, health insurance, and medical access than men and women of lower socioeconomic status. The alternative would be a dramatic change in the medical system, ensuring that health care is provided to all regardless of their race, class, or gender.

According to this perspective, what we have in place is a medical system driven by economics. In their investigation of pharmaceutical companies in the United States and Latin America, Rebeca Jasso-Aquilar and Howard Waitzkin (2011) documented how the government, transnational corporations, and international governance bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) are favorable partners with pharmaceutical companies. WHO, while it has promoted various initiatives and funding for mental health in low- and middle-income countries (Saraceno and Saxena 2004), also “contributed to the expansion of the market for pharmaceutical products and health insurance companies, while generally disregarding culturally-based ways of healing and patient–healer interaction” (Jasso-Aquilar and Waitzkin 2001, p. 249). The researchers warn about the increasing reliance of poor countries on a Western model of disease and treatment.

The medical system itself ensures that those already in charge maintain power. In health care, no other group has greater power than medical physicians and their professional organization, the American Medical Association (AMA), established in 1847. On its website, the AMA identifies itself as “the nation’s most influential medical organization.” In his book The Social Transformation of American Medicine, Paul Starr (1982) explains how the AMA’s authority over the medical profession and education was secured in the early 1900s, with a series of events that culminated with the Flexner Report. The 1910 report was written by Abraham Flexner and was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and supported by the AMA. Through the report, Flexner and the AMA were able to pass judgment on the quality of each medical school, based on an assessment of its curriculum, facilities, faculty, admission requirements, and state licensing record. This report eventually led to strict licensing criteria for all medical schools, which led to the closure of schools that could not meet the new standards. Starr reveals that although the increased standards and school closures may have improved the quality of medical training and care, they also increased the homogeneity and cohesiveness of the profession. From 162 schools in 1906, the number of medical schools dropped to 81 by 1922. Some of the closed schools were exclusively for African Americans and women. According to Rose Weitz (2001), with the increasing cost of education and higher educational prerequisites, fewer minorities, women, immigrants, and poor students could meet the requirements. As a result,

fewer doctors were available who would practice in minority communities and who understood the special concerns of minority or female patients. At the same time, simply because doctors were now more homogenously White, male, and upper class, their status grew, encouraging more hierarchical relationships between doctors and patients. (Weitz 2001:327)

The legacy of the Flexner Report—higher medical standards and more limited access to medical education and care—continues to this day. Examinations of the social and economic backgrounds of medical students in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain confirm that medical students tend to be recruited from families with higher socioeconomic standing and with medical professionals among their members (Magnus and Mick 2000; Mathers and Parry 2009). African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans are the most underrepresented minority groups in the medical profession. Though together they make 25% of the U.S. population, only 6% of practicing doctors come from these groups (Association of American Medical Colleges 2010).

Income and Health

Feminist Perspective

According to Peter Conrad (2001b), illness and how we treat it can reflect cultural assumptions and biases about a particular group. Take, for example, the case of women and their medical care. Conrad explains that throughout history, there are examples of medical and scientific explanations for women’s health and illnesses that reflect dominant and often negative conceptions of women. Since the 1930s, women’s natural physical conditions and experiences, such as childbirth, menopause, premenstrual syndrome, and menstruation, have been medicalized. Medicalization refers to the process through which a condition or behavior becomes defined as a medical problem (Weitz 2001). Although the medicalization of these conditions may have been effective in treating women, various feminist theorists see it as an extension of medicine’s control of women (Conrad 2001b), specifically normal female experiences linked with the female reproductive system (Markens 1996), inappropriately emphasizing the psychological, biomedical, or sociocultural origins (Hamilton 1994). Once a condition is defined as a medical problem, medicine, rather than the woman herself, gains control of its diagnosis and treatment.

Menopause, a natural physiological event for women, was defined in the medical community as a “deficiency disease” in the 1960s when commercial production of estrogen replacement therapy became available (Conrad 2001b; Lock 1993). Although a few medical writers refer to menopause as a natural process, many continue to describe it as a “hormonal imbalance” that leads to a “menopausal syndrome” (Lock 1993). Though estrogen replacement treatment has been presented as a means for women to retain their femininity and to maintain good health, feminists argue that menopause is not an illness; actually, estrogen therapy may not be necessary and may be dangerous (Conrad 2001b) and may do little to improve the quality of older women’s lives (Haney 2003).

Studies have suggested that the meanings and experiences of menopause may also be bound by cultural definitions. In North America, where women are defined by their youth and beauty, aging women are set up as a target for medicalization. In Japan, however, public attention focuses on a woman’s life course experience. For a middle-aged Japanese woman, what matters is how well she fulfills her social and familial duties, especially the care of elderly family members, rather than her physical or medical experiences. The Japanese medical community has a different perspective on menopause than its American colleagues do: most doctors in Japan define menopause as natural and an inevitable part of the aging process (Lock 1993). Asian American midlife women also report lower rates of physical and psychological symptoms related to menopause compared with midlife women from other ethnic groups (Sievert et al. 2007).

Gender salary inequality exists in the medical profession. Overall, female physicians earn less than male physicians, even after controlling for specialty, practice type, and hours worked (Seabury et al 2013).

© George Steinmetz/Corbis

The gender pay gap we discussed in Chapters 4 and 9 also exists among physicians. Historically, female physicians earn less than male physicians, the difference previously attributed to specialty choice (women selecting general practice, while men choose specialty fields) and hours worked (women working less hours than men). However research has confirmed that salary differences continue to exist, even after controlling for specialty, practice type, and hours worked. Seth Seabury, Amitabh Chandra, and Anupam Jena (2013) reported that the 1987–1990 earnings of male physicians were higher than those of female physicians by $33,480. Though they also controlled for differences in hours worked and years of experience, the gender gap in physician earnings continued to increase over time: $34,620 in 1996–2000 and $56,019 in 2006–2010.

Interactionist Perspective

From the interactionist perspective, health, illness, and medical responses are socially constructed and maintained. In the previous sections, we discussed how health issues are defined by powerful interest or political groups. We just reviewed how the medicalization of women’s conditions reflects our cultural assumptions or biases about women. Each example demonstrates how social, political, and cultural meanings affect our definition and response to health and illness.

A patient’s experience with the medical system can be disempowering (Goffman 1961), but the experience can be mediated by social meaning and interpretations (Lambert et al. 1997). According to Suni Peterson, Martin Heesacker, and Robert C. Schwartz (2001), when people contract a disease, they define their illness according to a socially constructed definition of the disease, which includes a set of images, beliefs, and perceptions. Patients use these definitions to create a personal meaning for their diagnosis and to determine their subsequent behavior. The authors argue that these social constructs have a greater influence on the patient’s actions and decisions about his or her health than recommendations from health professionals do.

Sociologists also examine how the relationship between doctors and their patients is created and maintained through interaction. In particular, sociologists focus on how medical professionals use their expertise and knowledge to maintain control over patients. Research indicates that doctors’ power depends on their cultural authority, their economic independence, cultural differences between patients and doctors, and doctors’ assumed superiority to patients (Weitz 2001). Studies consistently demonstrate the systematic differences in the level of information provided by physicians to their patients. Although differences might be attributed to the doctor responding to a patient’s particular communication style, researchers argue that information varies according to the doctor’s impressions of a patient (e.g., intelligence), subjective judgments about what information the patient needs (Street 1991), and status differentials between doctor and patient (male vs. female or White vs. non-White) (Peck and Conner 2011). Educated and younger patients tend to receive more diagnostic information, as do patients who ask more questions and express more concerns; doctors are likely to communicate as equals with their educated, older male patients (Street 1991). African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics are more likely than Whites to experience difficulties in communicating with their doctors. The difficulties include not understanding their doctors, not feeling that their doctors are listening to them, and having questions for their doctors that they did not ask (Collins et al. 2002).

Interactionists and social constructionists also investigate how a disease is socially constructed. This doesn’t mean that disease and illness do not exist. Rather, the focus is on how illness is created and sustained according to a set of shared social beliefs or definitions. In his essay “The Myth of Mental Illness,” Thomas Szasz (1960) argues that mental disorders are not actually illnesses. He considers mental illness a convenient myth to cover up the “everyday fact that life for most people is a continuous struggle” (Szasz 1960:118). The disease of mental illness is constructed and maintained through a set of medical, legal, and social definitions. The social construction of disease has also been applied to infertility (Greil, McQuillan, and Slauson-Blevins 2011), attention-deficit disorder (Mather 2012), and HIV/AIDS.

For a summary of sociological perspectives on health and medicine, see Table 10.2.

Health Inequalities and Problems

Gender

As noted in Table 10.1, women live about five years longer than men. The three leading causes of death for males and females are identical: heart disease, cancer, and stroke. Although women live longer than men, women experience higher rates of nonfatal chronic conditions (Waldron 2001; Weitz 2001). Men experience higher rates of fatal illness, dying more quickly than women when illness occurs (Waldron 2001; Weitz 2001).

These differences in mortality have been attributed to three factors: genetics, risk taking, and health care (Waldron 2001). Biological differences seem to favor women; more females than males survive at every age (Weitz 2001). Because of differences in gender roles, men are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors or potentially dangerous activities: driving too fast or incautiously, using legal or illegal drugs, or participating in dangerous sports (Waldron 2001). The workplace offers more dangers for men. More men than women are employed, and men’s jobs tend to be more hazardous (Waldron 2001); about 9 of every 10 fatal workplace accidents occur to men (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014a). Finally, because women obtain more routine health examinations than men do, their health problems are identified early enough for effective intervention (Weitz 2001). Typically, women eat healthier diets and smoke and drink less alcohol than men do (Calnan 1987).

According to the Men’s Health Network (2002), “no effective program exists which is devoted to awareness and prevention of the leading killers of men.” Although men die of cancer at twice the rate of women by the age of 75, there is little education for men in cancer self-detection and prevention. Whereas there is a popular national campaign for breast cancer, there is no national educational campaign teaching men how to self-examine for testicular cancer, a leading killer of men from 15 to 40 years of age. In addition, there are no quality educational programs regarding prostate cancer. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men, after skin cancer.

Education

A similar relationship has been documented between education and health—the higher your education, the better your health (no matter how it is measured—mortality, morbidity, or other general health measures). Education might be a more important correlate to good health than is one’s occupation or income (Grossman and Kaestner 1997), as it serves as a pathway to health because it is a resource itself (Mirowsky and Ross 2005).

Recent studies on the effects of compulsory education in Sweden, Denmark, England, and Wales consistently identify that a longer educational experience leads to better health (Kolata 2007). Michael Murphy and his colleagues (2006) identified mortality trends by educational level for Russian men and women between 1980 and 2001. Murphy et al. concluded that better-educated men and women had a significant mortality advantage over less-educated men and women. In 1980, life expectancy at age 20 for university-educated men was three years greater than for men with only an elementary education. By 2001, however, the gap between university- and elementary-educated men had increased to 11 years. Similar differentials were also noted among Russian women.

Researchers suggest that education helps individuals choose and practice a healthier lifestyle regarding diet, exercise, and other health choices. Highly educated men and women are likely to visit their primary physicians more often and regularly and may be more willing to use new medical technologies or medicines. Knowledge about the health consequences of smoking and drinking has been shown to decrease smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Educated parents will also transmit their healthier lifestyle to their children (Grossman and Kaestner 1997). Education represents both the long-term influence of early life circumstances and the influence of adult circumstances on adult health (Beckles and Truman 2011).

Researchers have demonstrated the link between education and future orientation. Future-oriented individuals attend school for longer periods. Educated individuals are able to link their current actions to their future, not only for their education but also for preventative health care practices. For example, a future-oriented person will say, “I’m going to college now so that I can have a good job when I graduate.” Applied to health behaviors, the same person will say, “I won’t start smoking because I know there are long-term health consequences of smoking.” Studies have shown that men and women who discount the future are more likely to become addicted to alcohol or other drugs (Becker and Mulligan 1994).

For more information about what other demographic characteristics are related to health care utilization, refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature.

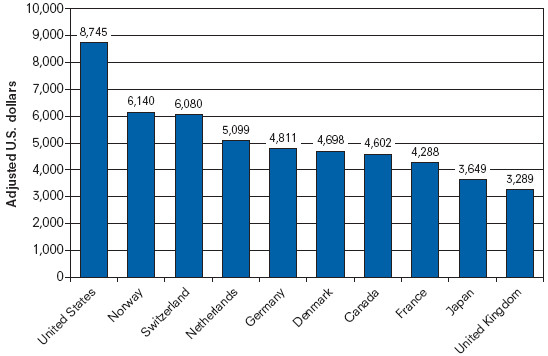

Figure 10.5 Total health expenditures per capita, United States and selected countries, 2012 (or nearest year)

SOURCE: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2014.

Inactivity and Health

Exploring social problems

Health Care Utilization

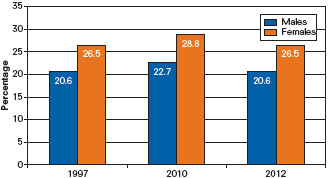

Figure 10.2 Percentage of Americans who had doctor, emergency department, or home visits four to nine times in the past 12 months, by gender

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics 2014.

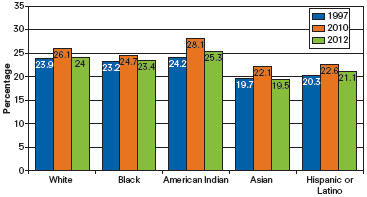

Figure 10.3 Percentage of Americans who had doctor, emergency department, or home visits four to nine times in the past 12 months, by ethnicity

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics 2014.

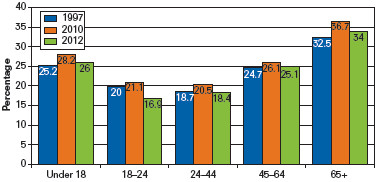

Figure 10.4 Percentage of Americans who had doctor, emergency department, or home visits four to nine times in the past 12 months, by age

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics 2014.

What Do You Think?

Multiple social factors determine how much health care people use, the types of health care they access, and the timing of that care. Gender, race and ethnicity, and age are just some of the demographic characteristics tracked by medical and public health researchers.

Health care utilization for 1997 through 2012 is presented in Figures 10.2 through 10.4. Health care utilization is defined as accessing a doctor, visiting an emergency department, or having a home visit four to nine times in the last year and is reported by percentages for each group.

Review each figure and identify the group or groups with the lower percentages of utilization.

What types of educational or outreach programs would increase the number of health care visits?

Immigrant Health Care Use

The Cost of Health Care

The United States spends about 17% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care—the largest expenditure in this category among industrialized countries. (A per capita spending comparison with other countries is presented in Figure 10.5.) In 2012, total health care spending reached $2.8 trillion, with an average of $8,915 spent per person in health expenses (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2014a). U.S. national health care spending had grown more slowly after 2010, attributed to the Great Recession and to a sluggish economy. More Americans delayed visits to their doctors or hospitals, reduced their prescription drug purchases (Pear 2012), or lost their insurance coverage along with their jobs (Lowrey 2012). Changes in Medicare’s payment policies, growth in patient cost-sharing, and state efforts to contain Medicaid costs have also been identified as contributing to the decline in health spending (Holahan and McMorrow 2013).

Even though the U.S. health system is the most expensive in the world, “comparative analyses consistently show the United States underperforms relative to other countries on most dimensions of [health] performance” (Davis et al. 2007:viii). In their pre–Affordable Care Act analyses of health care systems and outcomes in Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Karen Davis and her colleagues (2007) concluded that the United States failed to achieve better health outcomes and scored last on the dimensions of access, quality, efficiency, and equity despite spending the most per capita on health care.

The fastest-growing sector of medical care is prescription drug spending. In 2012, $263.3 billion was spent on prescription drugs. The cost of drugs remains a significant burden for elderly Americans.

Jose Luis Pelaez Inc./Getty Images

Given our lack of universal health care coverage, when compared with these other nations, more Americans are uninsured or underinsured and are more unlikely to seek necessary care because of costs. Davis and her colleagues (2007) identify how

other nations ensure the accessibility of care through universal health insurance systems and through better ties between patients and the physician practices that serve as their long term “medical home.” . . . It is also apparent that the U.S. is lagging in adoption of information technology and national policies that promote quality improvement. (p. viii)

(Information systems in countries such as Germany, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom enhance the ability of physicians to monitor patients’ chronic conditions and medication use. These countries also routinely use nonphysician clinicians to assist with patients with chronic diseases.) Germany ranked first on access to health care (the ability of patients to obtain affordable care in a timely manner), and the United Kingdom ranked first for health care quality (safe, coordinated, and patient-centered health care), efficiency (maximizing the quality of care and outcomes given the system’s resources), and equity (providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status). The United States ranked last on both measures.

The cost of medical care, particularly out-of-pocket expenses, is a financial burden even to those with health insurance. Harvard researchers concluded that illness or medical bills contributed to 62% of all bankruptcies in 2007 (Sack 2010). More than three fourths of those with medical debt had medical insurance (Sack 2010). Though spending on prescription drugs in the United States is the highest in the world, economic hard times caused some patients to alter their spending or their dosage of prescription drugs (Saul 2008). Through the first eight months of 2008, the number of all dispensed prescriptions was lower than in the same period of time in 2007 (Saul 2008). The decrease was attributed to individual cost-cutting measures, causing concern among physicians about the health and well-being of their patients. Patients reduced their medications (cutting their pills in half or taking medications every other day) or, among those who could no longer afford their medications, stopped taking their medicine altogether without consulting their physician (Saul 2008).

Policy makers and consumers have been keeping an eye on the cost of prescription drugs, one of the fastest-growing sectors of medical care. Increases in drug costs are expected to outstrip the overall growth in health care spending for the next 10 years. Spending for prescription drugs in 2012 totaled $263.3 billion. Out of this total, about $47 billion was out-of-pocket expenses (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2014b).

Rising Medical Costs Analysis

The Uninsured Population

A year before the full implementation of the ACA insurance mandate, surveyed Americans reported the primary reason for not being insured was the affordability of coverage, followed by loss of employment (Kaiser Family Foundation 2014). (Refer to the In Focus discussion for a summary of health insurance plans.) Data from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that 42.0 million Americans or 13.4% of the U.S. population had no health insurance at any time during 2013 (Smith and Medalia 2014). As reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation (2014), almost a third of uninsured adults went without medical care due to cost. Most uninsured were in low-income working families; nearly 8 in 10 were in a family with a worker. Adults were more likely to be uninsured than children. People of color were at a higher risk of being uninsured than non-Hispanic Whites.

The Kaiser Family Foundation (2014) tracked ACA enrollment data for most of 2014, confirming that the U.S. uninsured rate is falling. The data reveal that over 8 million selected plans through the federal or state Marketplaces, though the 2013 online enrollment was plagued by serious technological glitches. Data also show that Medicaid enrollment grew by 8 million, highest among states that chose to expand Medicaid eligibility under ACA.

Expanding health care coverage has many benefits. In 2008, Oregon’s Medicaid agency realized that it had enough funds to provide health insurance to an additional 10,000 adults (Oregon Health Study 2012). The agency decided to distribute the extra funds via a lottery system, drawing names to determine who would receive the Medicaid coverage. As part of the implementation, the Oregon Health Study was initiated to track the social, economic, and health outcomes among those enrolled in Medicaid and those who were not. Results of the study will provide policy makers with data on the effects of expanding health insurance at both individual and system levels. After a year of tracking the two study groups, Amy Finkelstein and her colleagues (2011) concluded that enrollment in Medicaid increased access to and use of health care (including preventative care and regular office or clinic visits), increased financial security (decreasing the probability of having an unpaid medical bill sent to a collection agency), and improved health and well-being (reporting to be in good to excellent health, increased probability of not screening positive for depression) compared to those who were not enrolled in the Oregon Medicaid program.

The Kaiser Family Foundation (2014) report concludes,

Even with the availability of new coverage options, millions remain uninsured. Previous analyses show that many poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid will continue to be at risk to be uninsured. People of color, people living in the South, and individuals living in rural areas are especially at risk to be left out of ACA coverage expansions.

The program’s second enrollment period began in the fall of 2014. National surveys reveal that the majority of Americans (56%) disapprove of the law, while 37% approve (McCarthy 2014).

In Focus

U.S. Health Insurance and Health Care Delivery Systems

The U.S. health care system is often referred to as a private health care system, but in reality, it is a mixed system of public and private insurance (Oberlander 2002). Refer to the Taking a World View section of this chapter for more information. Most Americans receive health insurance from their employers. This type of insurance is referred to as group insurance or as employment-based private insurance. Employers buy into a health insurance program, paying for part or all of the cost of the insurance premiums. A premium is a monthly fee to maintain your health coverage.

Under the Affordable Care Act, health insurance coverage was expanded through three avenues: subsiding insurance premiums for lower-income individuals and families, expanding the coverage of Medicare and Medicaid, and legally requiring everyone to sign up for a policy.

That handy insurance card in your wallet identifies your insurance provider, the amount of your deductible (payment due at the time of service), and the amount of coverage for prescription drugs or emergency services. There are many different types of group insurance programs:

Fee-for-service plan. Under this plan, also known as an indemnity health plan, insurance companies pay fees for services provided to the people covered by the policy. This type of program emphasizes patient choice and immediate patient care.

Health maintenance organization (HMO). These organizations operate as prepaid health plans. For your premium, the HMO provides you and your family comprehensive care. This plan is also known as managed health care, a plan that controls costs by controlling access to care. You’ll be assigned to a primary care provider, who will provide most of your medical care, but if necessary, that doctor will refer you to specialists within the HMO practice or to providers contracted by the HMO. Under the plan, there is limited coverage for any treatment outside the HMO network.

Preferred provider organization (PPO). A PPO is a combination of the fee-for-service and HMO plan. With a PPO, you can manage your own health care needs by selecting your own doctors. These specialists will be on a preferred provider list supported by the PPO plan. If you use a provider outside your plan, you may have to pay a larger percentage of your health care expenses.

Federal health plans. Medicare is available to Americans 65 years or older or those with disabilities, whereas Medicaid pays for medical and long-term care for the poor; low-income children, pregnant women, and elderly; the medically needy; and people requiring institutional care.

Community, Policy, and Social Action

Health Care Reform

During his first administration, President Bill Clinton said problems connected with the U.S. health care system were the most pressing in the United States. In 1993, Clinton pushed for passage of the Health Security Act, an attempt at comprehensive health care reform. The act would have required all employers to provide health insurance to their employees and would have given small businesses and unemployed Americans subsidies to purchase insurance. After Congress rejected Clinton’s health care plan, Americans looked to the private market to restrain health care costs and to enhance patient care and choice. U.S. medicine moved aggressively toward managed care arrangements, HMOs, and for-profit health plans (Oberlander 2002).

Sixteen years later, with Democratic majorities in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate, President Barack Obama declared “a season for action. . . . Now is the time to deliver on health care” (Obama 2009). After months of contentious and politically charged debate, Congress passed a compromise health reform bill in March 2010. Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, along with the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, into law. Several ACA elements went into immediate effect: young adults up to age 26 remain covered by their parents’ health insurance, plans were available for those with preexisting conditions, and lifetime limits on coverage were eliminated.

The full implementation of the law was challenged in the country’s highest court. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA, examining specifically the individual health insurance mandate and the portion of the law that will require states to expand their Medicaid rolls by 2014. The majority of justices likened the penalty for not obtaining health insurance to a tax. “Because the Constitution permits such a tax, it is not our role to forbid it, or to pass upon its wisdom or fairness,” wrote Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. (quoted in Liptak 2012:A1). The Medicaid expansion was upheld by the Court, but states would be permitted to keep their current federal money for Medicaid while refusing to expand the program. The Court ruled that states could decide whether to go along with the expansion without penalties to their existing Medicaid payments (Liptak 2012).

The expansion of Medicaid has been controversial, not only for the increased cost to states but also because of claims that the program is ineffectual and may also be associated with worse health (Belluck 2012). More than a dozen Republican governors announced that their states would not comply with the Medicaid expansion. However, most governors from both parties responded to the ruling with caution, stating that they would need to study the impact of Medicaid expansion on their state’s budget and on their uninsured population (Cooper 2012). The Congressional Budget Office (2012b) estimated that the Supreme Court’s decision would lead to about 6 million fewer people being covered by the federal Medicaid program, yet half of them should gain private insurance coverage through health insurance exchanges established by ACA. The other half, a predicted 3 million, would be uninsured.

By 2014, all citizens and legal residents had to purchase health insurance or face an annual fine. Additionally, states are required to expand Medicaid coverage to those with incomes at 133% of the federal poverty line. Another feature of the law is elimination of gender rating, using gender as a factor in setting health insurance rates. It is estimated that by 2016, the ACA will increase the number of nonelderly people with health insurance by 30 to 33 million (Congressional Budget Office 2012a).

Passing the Affordable Care Act

State Health Care Reforms

Several states aggressively moved forward on health reform, and several—Florida, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington—expressed commitment to providing health coverage for all their citizens. It is unclear how implementation of the ACA will impact these state plans. Following are summaries of three state plans.

Hawaii was one of the first states to act on health care reform. In 1974, the state passed the Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Act, requiring employers to provide health insurance for all employees working more than 20 hours per week and to pay at least 50% of the cost. Hawaii is the only state that requires employer payments to medical insurance under a congressional exemption of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). ERISA bars states from requiring all employers to offer health insurance, from regulating or taxing self-insured plans, and from mandating the specific benefits to be covered by employer health plans (Beatrice 1996). Hawaii’s plan also limits employees’ share of the insurance premium expenses to no more than 1.5% of their income. Recently, there has been a call to repeal or at least revise the Prepaid Health Care Act because of increasing health care costs. The percentage of uninsured Hawaiians is 7.8% (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, and Smith 2012).

Massachusetts became the first state to provide universal health care coverage to all its residents in 2006. The plan reduced the number of uninsured in the state to 3.7% (Smith and Medalia 2014), the lowest in any state. The plan allows the state to provide sliding-scale coverage, low-cost coverage, and free insurance coverage to uninsured residents depending on their income, age, or employment status. Individuals who can afford health insurance will be penalized on their state income taxes if they do not purchase it. There were modest provisions included in the plan to control costs, but not enough. Massachusetts spends 23% more per person on health care ($9,000) than the national average ($8,000). While spending continues to be a concern, analysts have noted how health care reform has led to gains in access to and use of health care in the state (Long, Stockley, and Dahlen 2012). Massachusetts government and health industry officials agreed that universal coverage would not be sustainable if they did not address the growth of health care spending (Sack 2009). In 2012, the state legislature passed a bill that would not allow health care spending to grow any faster than the state’s economy through 2017 (Goodnough 2012).

MinnesotaCare became law in Minnesota in 1992. Also known as the Health Right Act, the legislation included a variety of laws aimed at reducing costs and expanding access to health care for the uninsured (Beatrice 1996). MinnesotaCare is funded through a tax on health care providers and through enrollee premiums (based on family size, number of people covered, and income) (Sacks, Kutyla, and Silow-Carroll 2002). The act set price controls for health care spending (repealed in 1997), set statewide managed care guidelines, initially mandated that all non-HMO physicians follow a state fee structure (repealed in 1995), placed all HMOs under the regulation of the Commission of Health, and mandated that HMOs be nonprofit (Citizens Council on Health Care 2003). The act also subsidized health insurance for low- and middle-income uninsured families and individuals. Minnesota placed all MinnesotaCare recipients into HMOs (Beatrice 1996; Citizens Council on Health Care 2003). A small number of Minnesotans, about 9.2%, are uninsured (DeNavas-Walt et al. 2012).

Children’s Health Insurance Program

The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was adopted in 1997 as an amendment to the Social Security Act, Title XXI. The program is administered under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). CHIP enables states to implement their own children’s health insurance programs for uninsured low-income children 18 years old or younger and targets the children of working parents or grandparents. For example, a family of four that earns as much as $44,700 a year (in 2011) is eligible. The insurance plan pays for regular checkups, immunizations, prescription medicines, and hospitalizations. CHIP uses comprehensive outreach materials and educational programs to recruit eligible children and their families, especially through elementary and secondary schools. In many states, as CHIP enrollments began, so did Medicaid enrollments. In 2011, the number of children enrolled in CHIP had reached a record high of more than 7.7 million.

Based on his concern that CHIP expansion would be too costly and would be a step toward universal health coverage, in fall 2007, George W. Bush vetoed a House bill that proposed coverage for more than 10 million children as well as expansion of coverage to include dental services, mental illness, and pregnant women with low incomes. The expansion bill was supported by many state governors whose states were running out of federal funds to support the program (Pear 2007). CHIP advocates accused the president and his congressional supporters of placing their concerns for socialized medicine over the necessary expansion of health coverage for children. With the House unable to override the president’s veto, the administration promised to work with Congress on a bill compromise.

In 2009, Obama signed the CHIP expansion bill. The measure provided coverage to an additional 4 million uninsured children over the next five years, raising the total number of uninsured children covered by the program to 11 million. Obama praised the program for providing access to quality affordable health care and emphasized the program’s importance during a time when families had lost their jobs and health insurance. The bill was passed with partisan support from House and Senate Democrats. The expansion was financed with a 62-cent-per-pack increase in the federal tax on cigarettes.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 maintains CHIP eligibility standards through 2019 and provided funding to promote Medicaid and CHIP enrollment.

Eradicating Black Fever

Taking a World View

Not-So-Foreign Models of Health Care

Opponents of health care reform equated Obama’s plan to “socialized medicine,” believing that increasing government control of health care is intrusive and restrictive. Journalist T. R. Reid (2009) describes the term as a powerful political weapon, first used in 1947 to disparage President Truman’s national health care proposal. But, as Reid explains, the argument against socialized medicine is flawed. First, most national health care systems are not socialized. Many countries provide universal health care using private doctors, hospitals, and insurance plans. In fact, there is no single health care system in the world that is exclusively government owned and operated. Second, the United States already has socialized medicine, government-run medicine, in the form of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Medicare system.

As Reid (2009) explains, “We’re like no other country, because the United States maintains so many separate systems for separate classes of people” (p. 21). In his 2009 book The Healing of America: A Global Quest for Better, Cheaper, and Fairer Health Care, Reid identifies the four separate systems of health care in our country:

- Bismarck model. For most working Americans under 65 years of age, health care coverage is similar to the health systems in Germany, France, and Japan. Under this model, the worker and the employer share the cost of health insurance premiums.

- Beveridge model. Native Americans, military personnel, and veterans are covered under health care systems much like Great Britain and Cuba. Care is provided by doctors who are government employees working in government-owned clinics and hospitals. Patients who use this system never receive a medical bill.

- National health insurance model. Americans over the age of 65 are covered under Medicare, a system similar to the Canadian health system. Most health care providers are private, but the payer is a single government-run insurance program that every citizen pays into.

- Out-of-pocket model. Americans without a health insurance policy are no different from citizens from poor countries such as Cambodia or parts of rural China or India. If medical care is available, individuals will have to pay the bill out of their own pocket. Care is often available from emergency rooms or community-based free clinics.

In his analysis of these different models of care, Reid (2009) concludes that no system is perfect. Health care reform debates are taking place in other countries.

Voices in the Community

Victoria Hale

In 2005, Victoria Hale was named by Esquire magazine as its businesswoman of the year. She is the director and founder of OneWorld Health, the first nonprofit pharmaceutical company in the United States.

Hale was working as an analyst for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and then at Genentech (a biotechnology firm) when she first envisioned her company. Her position in the pharmaceutical industry allowed her to see how drugs were being set aside simply because they were not making enough money. The industry dedicates less than 10% of its total research and development budget to eradicating diseases of the developing world, which account for 90% of the world’s total infections (Heffernan 2005). Of the more than 1,500 drugs marketed worldwide between 1974 and 2004, only 21, or 1.3%, were used to treat diseases of the developing world (Buse 2006).

She established OneWorld Health to accomplish what she believed the industry should be doing—investing in the development and distribution of drugs that could be used to eradicate diseases in the developing world. Says Hale, “We deliberately chose neglected diseases that others were not working on. . . . There has been little research done on these diseases, and limited money for research or development. We don’t choose projects because money is available, we choose projects and then we go find funding” (Roth 2006:2). OneWorld Health is funded by charitable contributions.

Hale’s strategy was simple. She searched for drugs whose patents had expired or were not being used because of low profit margins. The first drug OneWorld Health invested in was paromomycin, an antibiotic that cures a parasitic disease called visceral leishmaniasis, also known as black fever or kala-azar. The disease afflicts half a million people annually worldwide, particularly in Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Nepal, and Sudan. Hale discovered that the development of paromomycin had been shelved before its clinical trials were completed. After continuing and completing clinical trials with the drug, Hale found a company, Gland Pharma, based in Hyderabad, India, that agreed to produce paromomycin and sell it for $10 per full course of treatment, affordable for the poor people of India.

Victoria Hale combined her pharmaceutical background with a mission to reduce health inequities. She currently leads Medicines360.

John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation—See more at: http://www.macfound.org/fellows/781/#sthash.Vh2F6fC8.dpuf

The use of paromomycin was approved in India in late 2006. The government publicly announced its goal of eradicating the disease by 2010. Eradication dates have also been set in Bangladesh and Nepal for 2015. After dealing with the initial skepticism of the pharmaceutical industry and its executives, Hale’s OneWorld Health has been heralded as an innovative, socially minded organization. Hale’s work will continue: “You can’t take care of all two billion of the world’s poorest poor at one time. But you can go disease by disease and determine which one you can succeed with” (Roth 2006:2). OneWorld Health is working on three additional drugs—for malaria (the most severe parasitic disease), diarrhea (the number-two killer of children in the developing world), and soil-transmitted hookworm infection (nearly 2 billion people have active infections).

In 2009, Hale founded Medicines360. The organization’s mission is to “address unmet needs of women by developing innovative, affordable, and sustainable medical solutions,” beginning with access to birth control (Medicines360 2014).

Sociology at Work

Medicine

Matthew Peters – Class of 2013

Undergraduate Major: Sociology

Undergraduate Minors: Biology, Chemistry

All U.S. physicians complete four years of undergraduate school, four years of medical school, and three to eight years in an internship or residency program depending on their specialty. While no specific undergraduate major is required, all students must complete prerequisite coursework in biology, chemistry, physics, English, mathematics, and the social sciences (sociology) and humanities. Applicants must also submit letters of recommendation, Medical College Admission Test scores, and evidence of volunteer or service experience in a health care setting (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014b).

Matthew Peters

Courtesy of Matthew Peters

When he started his undergraduate program, Matthew Peters knew that he wanted to be a doctor, but didn’t know anything about sociology. But after taking two sociology courses, Matthew decided to become a Sociology major while remaining on his prerequisite track for medical school. He is currently in medical school and admits,

Sociology in many ways is what brought me to medicine. To my knowledge, there are not many physician-sociologists, but I believe that is beginning to change, primarily because our country is currently engaged in big conversations about the future of healthcare in our country, from the social determinants of health to health equity. On the patient-care side of things, I believe that my sociological imagination makes me a more aware, sensitive, and thoughtful physician. Although it is easy to become caught up in the science of medicine, my “soci-brain” (as my wife puts it) has a tendency to make me pull back, think about a patient’s social context, then use that perspective to shape the encounter and care of the patient.

Through his Sociology program, Matthew completed a summer internship at a federally funded community health center. The experience was invaluable:

Although my tasks as an intern were not always traditional sociological work, the position really opened my eyes to the experiences of various disadvantaged populations as I began to see the disparities they face to receive fair and equal care. Working with large homeless, immigrant, and recently released convict populations challenged me to rethink my idealistic views of medicine in our country, while also realizing that my draw to medicine isn’t simply a fascination or interest; it’s a vocation and a mission.

“Do what excites you—even if you do not immediately see how it connects to sociology. Sure, there are ‘traditional’ sociology careers that are great for some, but do not let yourself feel locked into something that you are not enthusiastic about,” says Matthew. “That is one of the best things about sociology—it helps us to be aware of the boxes that contain us in everyday life and step outside of them. Sociology is more than a skill set; it is a way of thinking that I believe can make you more successful in any field.”

State Prescription Drug Plans

In an effort to control drug costs for their residents, several states have offered innovative cost-control models. Pennsylvania is second to Florida in the proportion of its population that is 65 years or older (Pear 2002). More than 300,000 people in Pennsylvania are enrolled in the Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly (PACE) or PACENET. For PACE, men and women 65 years or older can enroll in the program if they have annual incomes less than $23,500 for an individual or $31,500 per couple. The program is financed largely from state lottery proceeds. The program requires the use of low-cost generic drugs, which account for about 45% of all filled prescriptions. PACE was established in 1984 with strong bipartisan support, but with the rising cost of drugs and the increasing number of patients, lawmakers are looking for more cost-cutting strategies (Pear 2002). Pennsylvania also supports PACENET, an assistance program available for elderly individuals with household incomes between $14,500 and $23,500, or between $17,700 and $31,500 per couple. PACE and PACENET members pay a $6 or $8 copay for generic prescription drugs.

U.S. laws prohibit the importation of drugs from other countries into the United States, unless their safety is certified by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health and Human Services Task Force on Drug Importation concluded that savings on foreign drugs were not as much as consumers would expect and warned about significant risks to consumers purchasing imported drugs. The report questioned the safety and effectiveness of foreign-made drugs.

At the release of the report, consumer and health advocates weighed in, criticizing the task force for failing to address the fundamental problem of providing affordable prescription drugs to those who cannot afford them. Unlike other countries, in the United States drug prices are set according to market demands. Critics often remark how U.S. patients subsidize the rest of the world’s drug supply. The U.S. constitutes less than 5% of the world’s population, but buys more than 50% of its prescription drugs (Werth 2013).

Despite the federal restrictions, several states and cities permit their residents to buy prescription drugs from other countries. Maine is the first state to allow residents to buy mail-order drugs from accredited pharmacies in Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. The FDA and Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America objected to the legislation, arguing that access to the foreign drugs would jeopardize patient safety. Supporters of the law argued that Maine residents would have access to affordable medication.

Community-Based Health Centers

Community health centers (CHCs) were based on neighborhood health clinics first established during the War on Poverty in the 1960s. CHCs are operated by a variety of nonprofit organizations, health departments, religious and faith-based organizations, medical organizations, and schools. Costs are covered through a variety of sources, ranging from private insurance to government contracts or grants. These centers have been called the most effective tool to reduce health disparities and can increase access to health care to the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, and other underserved populations (Hargreaves, Arnold, and Blot 2006).

The U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) administers the network of nearly 1,300 nonprofit centers, sometimes also referred to as Federally Qualified Health Centers. These centers provide comprehensive, culturally competent, quality primary health care to medically underserved communities and vulnerable populations. Health centers are located in every state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Pacific Basin. These centers served more than 21 million people in 2013. It is estimated that one of out every 15 people relies on a HRSA-funded clinic for primary care (HRSA 2014a, 2014b).

With a clinic motto of “Trust.Heal.Care.,” the Erie Family Health Center, based in Chicago, Illinois, serves more than 50,000 medical patients each year (Erie Family Health Center 2014). The clinic was established in 1957 by volunteer physicians with a mission of health care as a right, not a privilege. The clinic serves patients at 13 sites across the city, including several large primary care facilities and school-based health centers and a freestanding teen health provider. Almost 80% of its patients are Hispanics, 54% are served in Spanish, and 68% are female. Eighty-three percent come from households with incomes below the federal poverty line.

Under the ACA, a five-year $11 billion fund was established for the operation, expansion, and construction of 300 new health centers and the renovation of 600 clinics.

Chapter Review

- 10.1 Describe the social determinants of health

A sociological perspective addresses the social determinants of health. Research continues to demonstrate the relationship between the individual and society and the structural effects on health: how our health is affected by our social position, work, families, education, and wealth and poverty.

- 10.2 Explain the three measures of epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study of the patterns in the distribution and frequency of sickness, injury, and death and the social factors that shape them. Epidemiologists focus on communities and populations, addressing how health and illness experiences are based on social factors such as gender, age, race, social class, and behavior.

- 10.3 Describe how the different sociological perspectives address problems related to health and medicine

According to the functionalist perspective, illness has a legitimate place in society. Conflict theorists believe that patterns of health and illness reflect systematic inequalities based on ethnicity/race or gender and differences in power, values, and interests. Although the medicalization of such conditions as premenstrual syndrome and menopause may have been effective in treating women, various feminist theorists see this trend as an extension of medicine’s control of women. From an interactionist’s perspective, health, illness, and medical responses are socially constructed and maintained.

- 10.4 Identify the relationship between education and health

Researchers suggest that education helps individuals choose and practice a healthier lifestyle regarding diet, exercise, and other health choices. Highly educated men and women are likely to visit their primary physicians more often and regularly and may be more willing to use new medical technologies or medicines. Educated parents will transmit their healthier lifestyle to their children.

- 10.5 Summarize the different models of health care in the United States

There are four models of health care: (1) the Bismark model, in which the worker and the employer share the cost of health insurance premiums; (2) the Beveridge model, in which care is provided by doctors who are government employees in government-owned clinics and hospitals; (3) the national health insurance model, in which every citizen pays into a single government-run insurance program; and (4) the out-of-pocket model, in which patients pay for their care out of their own pocket.

Key Terms

- acute illnesses, 275

- epidemiology, 273

- fecundity, 273

- fertility, 273

- incidence rate, 275

- infant mortality, 274

- medicalization, 279

- morbidity, 275

- mortality, 274

- prevalence rate, 275

- sick role, 276

Study Questions

- How is health examined from a sociological perspective?

- How is illness functional in society? What behavior is expected from someone who is sick?

- Explain from a conflict perspective how health inequalities are shaped by conflict and competing interests between groups.

- Using eating disorders as the basis for your answer, examine how illness and disease are socially constructed.

- Review the inequalities of health and health care access by gender, race/ethnicity, and social class.

- Why is the United States the last industrial country to adopt a national health care program? Which sociological perspective(s) best explains why public and political support for health care reform has been difficult to achieve?

- Do you know what a “mommy job” is? Featured in print and television advertisements, a mommy job is a cosmetic surgical procedure that may include a breast lift, a tummy tuck, and liposuction to reduce the stretch marks, slackened skin, and excess fat that result from pregnancy and childbirth. Targeting women of childbearing age, the marketing of mommy makeovers has been described as an attempt to “pathologize the postpartum body, characterizing pregnancy and child birth as maladies with disfiguring aftereffects that can be repaired with the help of scalpels” (Singer 2007:E3). From a sociological perspective, is a mommy job a surgical necessity or an invention? What do you think?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.