Chapter 9 Work and the Economy

Learning Objectives

- 9.1 Describe the transition from agricultural to industrial production

- 9.2 Compare how the sociological perspectives explain social problems related to work

- 9.3 Explain the difference between unemployment and underemployment

- 9.4 Identify which forms of discrimination workers are protected against

- 9.5 Identify how labor unions have changed their membership strategy

News headlines in our country often refer to unemployment as a social problem. Between 2008 and 2009, the United States lost 8.4 million jobs, or about 6.1% of all payroll employment, the largest job loss since the Great Depression (Economic Policy Institute 2012). The Great Recession of 2007–2009 was referred to as “one of the most difficult financial and economic episodes in modern history” by former U.S. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke (2009).

Unemployment was no longer limited to people of color, immigrants, or the undereducated. Unique to the recession was its impact on the educated and the (formerly) middle class. Many more people, across different demographic groups, experienced the hardships of unemployment. For September 2014, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014a) reported that 9.3 million women and men were unemployed, an overall rate of 5.9%. This is the lowest unemployment rate since 2008. More than 146 million women and men were employed in the United States, about 63% of the population aged 16 years or older (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014a).

After the recession ended, unemployment rates declined in Asia, in India, and throughout the European Union (EU). In the EU, the unemployment rate was 11.5% in August 2014, with rates being highest in Greece and Spain (Eurostat 2014). The 2013 U.S. median household income was estimated at $51,759 (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014). The 2013 real household income was 8.0% lower than in 2007 ($54,489), the year before the recession.

Though political and economic attention has shifted to job creation, economic stimulus packages, and unemployment, these aren’t the only problems facing workers. For some, work remains a dangerous place, leading to injury or death. Others are victims of discrimination or harassment in the workplace. And for many men and women, even though they are employed, their paychecks do not provide a livable wage.

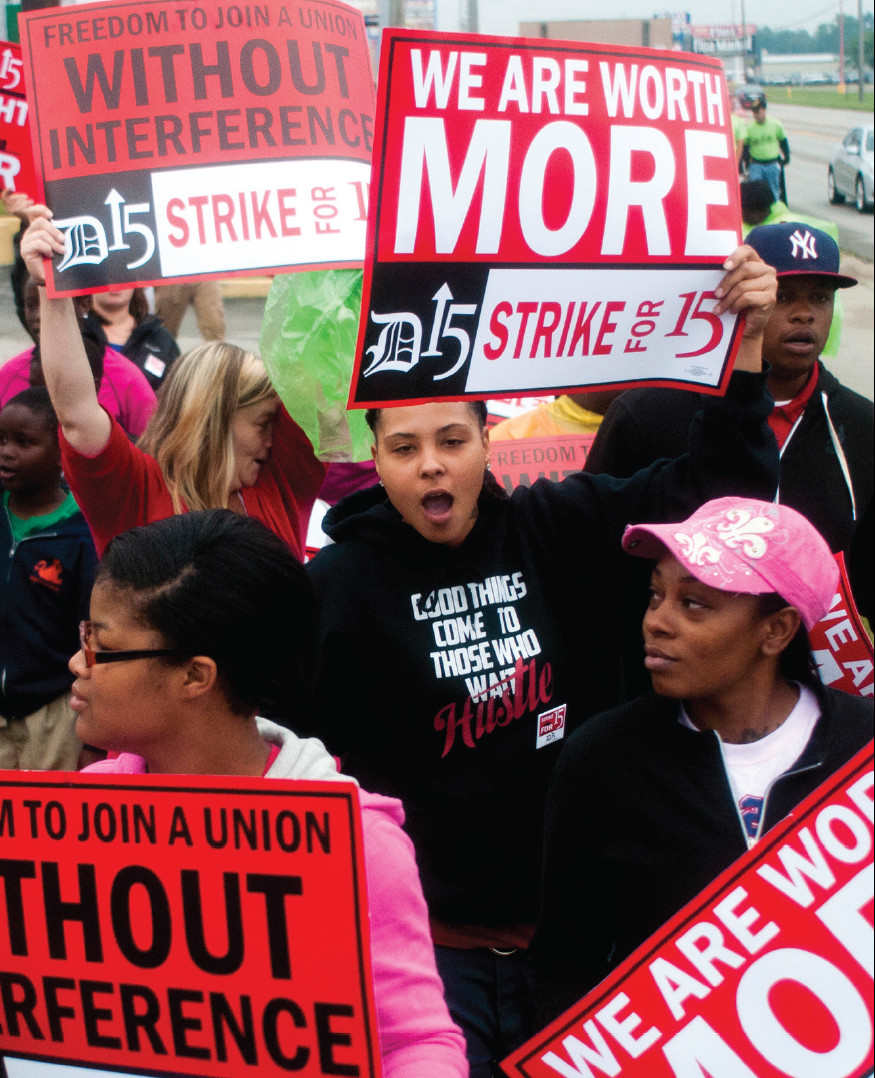

Beginning in 2012, hundreds of fast-food workers staged sit-ins or one-day work strikes around the country. Workers and protestors even appeared at McDonald’s corporate headquarters in Illinois just in time for the 2014 annual shareholder meeting. Holding signs that read, “Low pay is not okay” and “We are worth more,” workers and protest organizers were demanding a $15-per-hour wage and the right to unionize. On average, a McDonald’s employee makes $8.25 per hour before taxes.

Work isn’t just what we do; work is a basic and important social institution. It fuels our economy and provides economic support for individuals and families. Work is also important for our social and psychological well-being. Individuals find a sense of fulfillment and happiness, and for most, work provides a self-identity. Much of our social status is conferred through our occupation or the type of work we do. Because of the importance of work, problems related to work become categorized as social problems, as everyone’s problem. In this chapter, we examine the work that we do, the social organization of work itself, and the social problems associated with our work and economy. We begin first with a review of the changing nature of work.

What Was the Great Recession?

The Changing Nature of Work

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the means of production shifted from agricultural to industrial. In agrarian societies, economic production was very simple, based primarily on family agriculture and hunting or gathering activities. Each family provided its own food, shelter, and clothing. This changed during the Industrial Revolution, an economic shift in how people worked and how they earned a living. Family production was replaced with market production, in which capitalist owners paid workers wages to produce goods (Reskin and Padavic 1994).

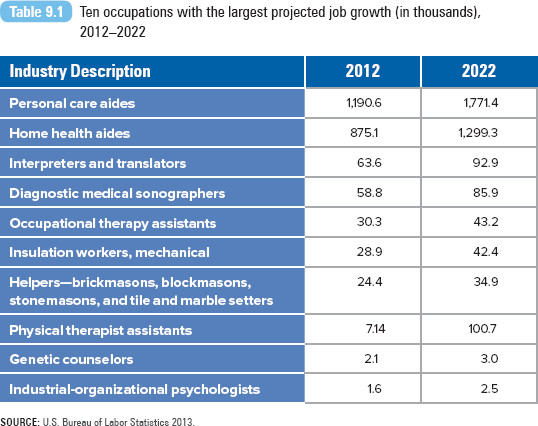

As a whole, we don’t produce goods anymore; we provide services. Since the late 1960s, the U.S. economy has shifted from a manufacturing to a service-based economy (Brady and Wallace 2001). In 1950, manufacturing accounted for 33.7% of all nonfarm jobs; by 2000, manufacturing’s share had dropped to 14% (Pollina 2003). The service revolution is an economy dominated by service and information occupations. Examine Table 9.1, which lists the 10 fastest-growing projected occupations between 2012 and 2022. Only one category involves manufacturing (brick and stonemasons), while the rest involve jobs in health care and service.

This shift has been referred to as deindustrialization, a widespread, systematic disinvestment in our nation’s manufacturing and production capacities (Bluestone and Harrison 1982). Less manufacturing takes place in the United States because most jobs and plants have been transferred to other countries. The expansion of industrialization in other regions such as Asia, the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, and Africa has encouraged managers to reduce their manufacturing costs by exporting manufacturing jobs there (T. Sullivan 2004). In addition, U.S. factories have closed as a result of mergers or acquisitions as well as poor business. And thanks to technological advances, it takes fewer people to produce the same amount of goods.

U.S. manufacturing lost 5.7 million or about 33% of manufacturing jobs in the 2000s. Affected areas have experienced devastating social and economic losses, turning some into ghost towns (Brady and Wallace 2001) or leading cities into deep debt or bankruptcy—the plight of Cleveland, Ohio, and Detroit, Michigan. The phenomenon was also observed in Great Britain in the 1970s and 1980s in cities such as Birmingham and Manchester (Carley 2000). Lost manufacturing jobs are often replaced with unstable, low-paying service jobs or no jobs at all. As a result, cities may experience a significant loss of revenue to support basic public services such as police, fire protection, and schools (Bluestone and Harrison 1982).

In addition to the transformation in the type of work we do, there has been a transformation in who is doing the work. The first significant workforce change began in World War II with the entry of record numbers of women into the workplace. In 1940, the majority of 11.5 million employed women were working as blue-collar, domestic, or service workers out of economic necessity (Gluck 1987). White and Black women’s entry into defense jobs signaled a major breakthrough. One fourth of all White women and nearly 40% of Black women were wage earners who had previously worked in lower-paid clerical, service, or manufacturing jobs.

By 1944, 16% of working women held jobs in war industries. At the height of wartime production, the number of married women in the workplace outnumbered single working women for the first time in U.S. labor history. Almost one in three women defense workers were former full-time homemakers. In Los Angeles, women made up 40% of the aircraft production workforce.

These heavy industry jobs may have paid better, but the jobs held an important symbolic value: these jobs were men’s jobs. After the war, although the proportion of women workers in durable manufacturing increased in many cities, many women were forced back into low-paying, female-dominated occupations (Gluck 1987) or back to their homes.

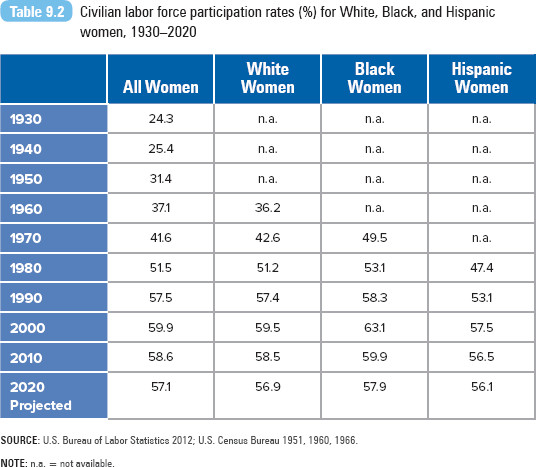

Labor force participation rates have steadily increased for White, Black, and Hispanic women since World War II (see Table 9.2). In 2012, 72.6 million or 58% of women aged 16 years or older were labor force participants (working or looking for work) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014b). Women dominated financial (53%), education and health services (75%), and leisure and hospitality (51%) occupations during that year (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014b). In 2010, for the first time in U.S. history, women outnumbered men in the workplace (nonfarm jobs)—50.3% versus 49.7%. Legislation ensuring gender equality, along with increasing higher education enrollment among women, has improved women’s value and participation in the labor market (Economist 2009).

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2012; U.S. Census Bureau 1951, 1960, 1966.

NOTE: n.a. = not available.

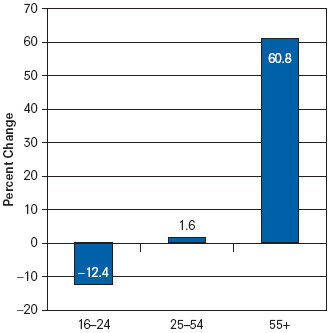

The second workforce change has been the record numbers of elderly Americans returning to work. Since the mid-1980s, the labor force participation rates of older Americans have consistently increased (Toossi 2005). In 2013, 31 million Americans aged 55 or older were employed in the labor force, reflecting a 38% participation rate (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014a). The percentage of Americans aged 55 years or older staying employed or going back to work after retirement is projected to increase by 2020, more than for any other age group (refer to Figure 9.1).

Although Americans are working longer partly because they are living longer, additional factors contribute to the increase in 55-plus employment. Government policies have eliminated mandatory retirements and outlawed age discrimination in the workplace. In 2000, older Americans were also encouraged to go back to work with the removal of age restrictions and taxes on their earned wages (Toossi 2005). Stung by the economic recession, older Americans are still delaying their retirement, deciding that they should work longer.

Figure 9.1 Projected percentage change in number of labor force participants by age group, 2010–2020

SOURCE: Toossi 2012.

Immigration is the source of the last workforce shift, affecting the numbers and diversity of labor force participants. The number of foreign-born workers rose from a low of 4.3 million in 1970, to 11.6 million in 1990, to 17.3 million in 2000. For 2013, there were 25.3 million foreign workers in the United States, about 16% of the labor force (Newburger and Gryn 2009; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014c). Foreign-born workers are more likely to be male, less educated, and younger (in their late 20s and early 30s) than native-born workers. Ronald Pollina (2003) predicted that, as our native population continues to age, the U.S. workforce will become increasingly dependent on foreign-born workers.

For 2013, foreign-born workers were more likely than native-born workers to be employed in service occupations and less likely to be employed in management, professional, and sales and office occupations. About 40% of foreign workers lived in the West and the Northeast (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014c). Immigrants settle in regions with perceived economic opportunities, seeking established ethnic enclaves providing interpersonal and job support (Mosisa 2002). The median weekly earnings of full-time foreign-born workers was $643, about 80% of the earnings of full-time native-born workers ($805).

What Was the Industrial Revolution?

Sociological Perspectives on Work

Functionalist Perspective

According to the functionalist perspective, work serves specific functions in society. Our work provides us with some predictability about our life experiences. We can expect to begin paid employment around the age of 18 years or after high school graduation (or we could delay it for four or five more years by attending college and graduate school). Your work may determine when you get married, when you have your first child, and when you purchase your home. Work serves as an important social structure as we become stratified according to our occupations and our income. Finally, even for the most independent among us, the way we live depends on the work of thousands—for our food, clothing, safety, education, and health. Our lives are bound to the products and activities of the labor force (Hall 1994).

Recall that from this perspective, work can also produce a set of dysfunctions that can lead to social problems (or that may be problems themselves). Employers encourage workers to become involved with their work, hoping to increase their productivity as well as their quality of work (a function). However, getting too involved in one’s work may lead to job stress, overwork, and job dissatisfaction for workers (all are dysfunctional). Although technology improves the speed and quality of work for some (a function), as machines replace human laborers, technology can also lead to job and wage losses (dysfunctions).

As some researchers have focused on the functions and dysfunctions of work, others have tried to understand the nature of work itself. Frederick W. Taylor, a mechanical engineer, offered an analysis that revolutionized 19th- and 20th-century industrial work. Using what he called scientific management, Taylor broke down the functional elements of work, identifying the most efficient, fastest, best way to complete a task. In one of his first research projects, Taylor determined the best shovel design for shoveling coal. He believed that with the right tools and the perfect system, any worker could improve his or her work productivity, all for the benefit of the company. In his book The Principles of Scientific Management, Taylor (1911) wrote, “In the past the man has been first; in the future the system must be first” (p. 5).

From a conflict perspective, capitalism produces a unequal social structure. Owners of the means of production occupy the highest position, while laborers occupy the lowest.

International Pub. Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Although scientific management in its pure form has rarely been implemented, Taylor’s principles continue to serve as the foundation for modern management ideology and technologies of work organization (Bahnisch 2000). Beyond simply changing how work was organized, Taylor offered his ideas about the organization of work: the need for defining a clear authority structure, separating planning from operational groups, providing bonuses for workers, and insisting on task specialization. In contrast, Max Weber ([1925] 1978) warned that in exchange for the efficiency and predictability of bureaucracy, workers would lose their individual freedom, ultimately dehumanizing their labor. Indeed, Taylor’s model shifted power to management, forcing skilled workers to give up control of their own work (Hirschhorn 1984), which was a cause for concern expressed by theorists from the next theoretical perspective.

Conflict Perspective

Power, explained Karl Marx, is determined according to one’s relationship to the means of production. Owners of the means of production possess all the power in the system, he believed, with little (probably nothing) left for workers. As workers labor only to make products and profits for owners, workers’ energies are consumed in the production of things over which they have no real power, control, or ownership (Zeitlin 1997). According to Marx, man’s labor becomes a means to an end; we work only to earn money. Marx predicted that eventually we would become alienated or separated from our labor, from what we produce, from our fellow workers, and from our human potential. Instead of work providing a transformation and fulfillment of our human potential, work would become the place where we felt least human (Ritzer 2000).

Modern systems of work continue to erode workers’ power over their labor. In an extreme case, 17 young Chinese men and women committed suicide at Foxconn Technology, a computer hardware company that makes products for Apple, Dell, and HP. The 2010 suicides and suicide attempts involved workers aged 18 to 24, recently hired by the company. Ma Xiangqian, a 19-year-old worker, leapt to his death from his dormitory floor. Company records revealed that Xiangqian had worked 286 hours in the month before he died, including 112 hours of overtime (three times the legal labor limit). He earned about $1.00 per hour, even with extra pay for overtime. Thousands of Foxconn factory workers resigned from their jobs (Barboza 2010).

Deskilling refers to the systematic reconstruction of jobs so that they require fewer skills and, ultimately, management can have more control over workers (Hall 1994). Although Taylor (1911) proposed scientific management as a means to improve production, sociologist Harry Braverman (1974) argued that by altering production systems, capitalists and management increase their control over workers. Once dependent on the workers’ abilities, the nature of work shifts to managerial and organizational priorities. Management, according to Braverman (1974), “controls each step of the labor process and its mode of execution” (p. 119). This heightened level of control and routinization increases worker alienation and hinders creativity and flexibility among workers. Deskilling may also limit job prospects for the employee, as job tasks and specialization become company specific, not transferrable to another (Jagoda 2013).

Although Marx predicted that capitalism would disappear, capitalism has grown stronger, and at the same time, the social and economic inequalities in U.S. society have increased. Capitalism has become more than just an economic system; it is an entire political, cultural, and social order (Parenti 1988). Modern capitalism includes the rise and domination of corporations, large business enterprises with U.S. and global interests. Conflict theorists argue that capitalist and corporate leaders maintain their power and economic advantage at the expense of their workers and the general public.

Deskilling: The Perils of Automation

Feminist Perspective

From a feminist perspective, work is a gendered institution. Through the actions, beliefs, and interactions of workers and their employers, as well as the policies and practices of the workplace (Reskin and Padavic 1994), men’s and women’s identities as workers are created, reproduced, and then solidified in the everyday routines of informal work groups and formal workers’ organizations (Brenner 1998). We already discussed the importance of World War II for women’s employment; but recall that after the war, there was pressure on women to resume their roles as housewives or to assume more appropriate occupations. As a gendered institution, work defined the roles appropriate for World War II women and defines them for women today. The workplace does not treat women and men equally. Women are concentrated in different—and lower-ranking—occupations than men, and women are paid less than men (Reskin and Padavic 1994).

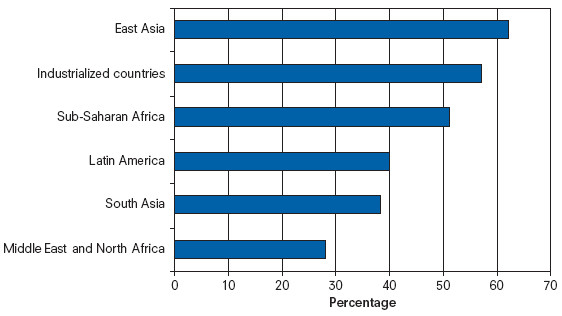

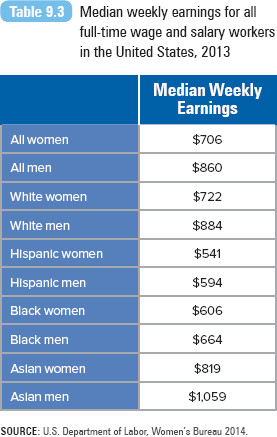

A fundamental feature of work is the gendered division of labor, the assignment of different tasks and work to men and women. This division of labor leads to a devaluing of female workers and their work, providing some justification for the differential compensation between men and women (Reskin and Padavic 1994). In the United States, as in most other countries, women earn less than men (England and Browne 1992). There is no country in the world where women make the same as or more than men (refer to Figure 9.2). In the early 1960s, U.S. women earned about 59 cents for every dollar earned by men (Armas 2004). By 2013, for every dollar a man earned, a woman made 78.3 cents (National Committee on Pay Equity 2014). (Refer to Table 9.3 for a comparison of women’s median weekly earnings by race, for 2013.)

In pay, compared with men, women are disadvantaged because they are in lower-paying feminized jobs or because they are paid less for the same work (Budig 2002). Sociologists and feminist scholars insist that no natural differences between men and women would lead to this. Instead, these researchers offer several structural explanations for the differences: differential socialization (women are socialized to pursue careers that traditionally pay less or are lower in status), differential training (men are better educated, so should be rewarded with higher pay), and workplace discrimination (Reskin and Padavic 1994). For additional discussion of these perspectives, refer to Chapter 4, “Gender.”

Figure 9.2 Women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s earnings, in U.S. dollars, 2003

SOURCE: UNICEF 2012.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau 2014.

A problem feminist advocates and scholars have addressed is workplace discrimination based on pregnancy or motherhood. In a 2006 study of women in the United Kingdom, one in six women identified revealing their pregnancy to their employer as one of the most challenging experiences of their work career (Phillips 2006). The U.S. federal government has enacted several laws protecting mothers against discrimination. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) allows both men and women to take 12 weeks of unpaid leave for the birth or adoption of a child. Feminist scholars argue that FMLA assumes that women can afford to take leave, perpetuating stereotypes that women are dependent on men as providers and that women, not men, are the primary caregivers and less dedicated employees (Reuter 2005).

Interactionist Perspective

The sociologies of work and symbolic interaction were developed side by side in the 1920s and 1930s at the University of Chicago. There are strong similarities between the two sociological perspectives: in the same way that symbolic interactionists are interested in how individuals negotiate their social order, the sociologists of work are interested in the negotiated order of work (Ritzer 1989). Interactionists address norms in the workplace, how workers interact with their peers, how workers deal with stress, and how workers find meaning in the work they do. This perspective allows us to understand the process by which individuals understand, interpret, and create their work.

For example, Geraldine Byrne and Robert Heyman (1997) interviewed nurses in the United Kingdom, investigating the relationship between their perceptions of work and patients and how it influenced their communication with patients. The researchers noted how nurses distinguished their work with “major trauma” and “minor” patients. They defined their work as more valuable and satisfying in trauma cases, giving them an opportunity to feel technically expert and rewardingly useful. Their time with minor patients was described as boring or repetitive and a small part of their daily work. Although nurses felt that all patients experience some anxiety in the hospital, they felt that those with more serious illnesses or injuries would be more anxious than others. As a result, they spent more time with the seriously ill or injured patients, but they made sure to “pop in” with all patients as a way of demonstrating that they had not forgotten about them and providing some nursing contact.

According to symbolic interactionists, we attach labels and meanings to an individual’s work (and major). If you meet a fellow student for the first time, one of the first questions you may ask is “What’s your major?” Why ask about a major? Think of it as a shortcut for who you are. Based simply on whether you are a Sociology major or a Physics major, people make assumptions about how much you study or your academic quality. This is no different from asking someone what he or she does for a living. These social constructs create an order to our work and our lives, but they can also create social problems.

Problems arise when these social constructs serve as the basis of job discrimination. A study by researchers from the University of Chicago and Massachusetts Institute of Technology revealed discrimination in the recruiting process based only on what was perceived about someone’s first name (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2003). Researchers sent 5,000 résumés in response to job advertisements in the Boston Globe and Chicago Tribune. First names were selected based on a review of local birth certificates. Fictional applicants with “White” first names—Neil, Brett, Emily, and Jill—received one callback for every 10 résumés mailed out. In contrast, equivalent “Black” applicants—with names such as Aisha, Rasheed, Kareem, and Tamika—received one response for every 15 résumés sent. Other aspects of discrimination were revealed in the study. If the résumé indicated that the applicant lived in a wealthier, more educated, or more-White neighborhood, the rate of callbacks increased. This effect did not vary by race.

Though employers report positive attitudes toward people with disabilities, actual hiring rates reveal an opposite trend. Since 1986, the jobless rate of people with disabilities has been around 66%. Researchers have attributed the persistence of stigma regarding the disabled and the negative impact on hiring them to a variety of reasons. For many, disability is associated with low or no ability, poor performance, or unsafe work behavior (Rubin and Roessler 2008). Employers are also concerned about the perceived costs of accommodations and the possibility of other workers demanding special consideration themselves (Schur, Kruse, and Blanck 2005). The stigma attached to disability is compounded by other personal characteristics such as age, race or ethnicity, or gender; these individuals are doubly disadvantaged in the workplace (McMahon et al. 2008).

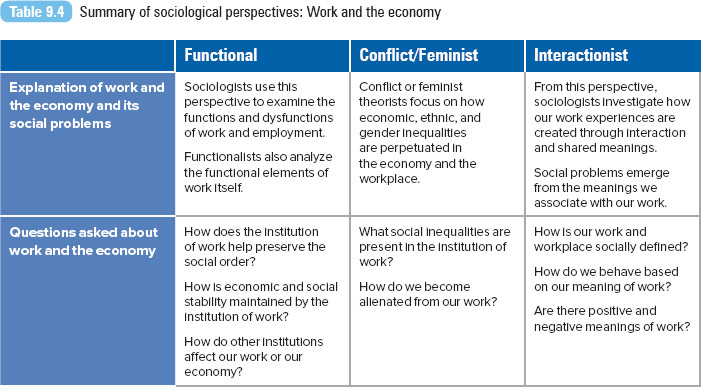

See Table 9.4 for a summary of all perspectives.

The American Dream in Crisis

Problems in Work and the Economy

Unemployment and Underemployment

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014a), about 146.6 million Americans were employed and 9.3 million were unemployed in September 2014. Compared with the (seasonally adjusted) unemployment rate of Whites, 5.1%, the rate was 11.0% for African Americans and 6.9% for Hispanics. Nearly 3.2 million individuals were long-term unemployed or unemployed for 27 weeks or more (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014a).

The recent recession has been characterized as a man’s recession or a “man-cession.” In 2008–2009, the U.S. unemployment rate for men increased more steeply than the rate for women, due largely to layoffs in manufacturing and construction, where men made up roughly 70% and 85% of the workforce, respectively (Cook 2009). On the other hand, women are concentrated in occupations that are more resistant to the economic decline, such as health, education, and public service. Health care employment has been among the strongest in this recession (Rampell 2010). Post-recession, as of September 2014, 5.9% of men aged 16 or older were unemployed, compared with 6.0% of women in the same age group (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014a).

During and after the Great Recession, the unemployment rate for young adults has been a concern in the United States and globally. In the United States, the unemployment for all four-year college graduates is 4.5%; however, the unemployment rate for recent four-year graduates is higher at 6.8% and for recent high school graduates is nearly 24% (Carnevale, Jayasundera, and Cheah 2012). A college degree has been described as “the best umbrella in this historic economic storm and the best preparation for the economy that is emerging in recovery” (Carnevale et al. 2012:1). For Europeans 15 to 24 years of age (level of education not identified), the rate of unemployment was 21.6% in 2011 (Eurostat 2012).

In addition to unemployment, we should be aware of another rate, underemployment. Underemployment is defined as the number of employed individuals who are working in a job that underpays them, is not equal to their skill level, or involves fewer working hours than they would prefer (taking a part-time job when a full-time job is not available). In September 2014, the number of people working part-time because of cutbacks or because they were unable to find a full-time job was 7.1 million (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014a).

There is significant variation in unemployment and underemployment rates. People who are young, non-college-educated, and members of ethnic/racial minorities have higher underemployment rates (Bernstein 1997). Minority group underemployment is significantly higher than underemployment among non-Hispanic Whites. Min Zhou (1993) reports that at least 40% of the members of each minority group he analyzed (Puerto Ricans, Blacks, Mexicans, Cubans, Chinese, and Japanese) were underemployed. In particular, Blacks and Puerto Ricans have the highest rates of labor force nonparticipation (were not in the labor force and had not worked in the last two years) and joblessness. Joblessness includes subemployment (individuals who were not in the labor force but worked within the last two years) and underemployment rates (based on either low wage or occupational mismatch). Recent immigrants, a large portion of the Asian and Hispanic minority groups, may have difficulty in securing employment because of lack of job skills or language proficiency and, as a result, are more likely underemployed than are native-born and non-Hispanic White workers (DeJong and Madamba 2001).

Scholars have documented the destructive effects of joblessness on overall health (Rodriguez 2001) and emotional well-being (Darity 2003). Unemployment has been consistently linked with higher levels of alienation, anxiety, and depression (Rodriguez 2001) and a lower sense of overall health (Darity 2003). Cross-national data reveal how long periods of unemployment are related to increased rates of suicide and spousal abuse (Darity 2003). Among Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites, long-term exposure to unemployment produces a “scarred worker effect.” The experience of unemployment undermines the worker’s will to perform, leading that person to become less productive and less employable in the future (Rodriguez 2001).

The Problem of Globalization

Globalization, introduced in Chapter 1, is a process whereby goods, information, people, communication, and forms of culture move across national boundaries. Though we tend to think of globalization as an economic phenomenon, we should not lose sight of its political, social, and cultural implications (Eitzen and Baca Zinn 2006).

Globalization has transformed the nature of economic activity (Eitzen and Baca Zinn 2006). It has been credited with bringing the world together—creating a world market where all businesses, employers, and employees must compete. This competition keeps corporations focused on innovation, quality, and production. Increasing productivity and output creates more jobs and stimulates economic growth (Weidenbaum 2006), creating a new middle class and reducing poverty in many countries (Yergin 2006). The United States has benefited from globalization, having experienced a doubling in foreign trade during the 1990s, which led to the creation of more than 17 million new jobs (Yergin 2006).

Yet, globalization has its dark side (Weidenbaum 2006). Foremost, worker security has declined everywhere, including in the United States. Skilled workers are threatened by the unfair competition of low-cost sweatshops, of cheaper labor to be found in other nations. More than 3 million U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost from 2001 to 2004 (Dobbs 2004). These high-paying jobs ($16 per hour) migrated to other countries, in a process characterized as the “race to the bottom.” Corporations are moving to lower-wage economies, shifting their production from the United States to Mexico to China (where the average manufacturing wage is 61 cents per hour) (Eitzen and Baca Zinn 2006).

There are conflicting assessments on the relationship between globalization and poverty. Some highlight how progress in poverty reduction has been limited and geographically isolated (Weller and Hersh 2006). Others conclude that globalization has reduced global poverty (pointing to the overall reduction of the number of poor according to the World Bank standard, discussed in Chapter 2), while also warning about the threat from the persistent inequality between rich and poor countries. Developed (rich) countries are able to reap more economic benefits from less developed (poor) countries through the system of globalization (Shin 2009).

Women are particularly vulnerable in the new global economy. The global assembly line is filled with girls and women engaged in work that is low-wage, temporary, part-time, or home-based and usually performed under unsafe working conditions. More than half the world’s legal and illegal immigrants are women—third-world women moving to postindustrial societies for jobs as nannies, maids, and sex workers (Eitzen and Baca Zinn 2006).

How to Stop Outsourcing Jobs

Exploring social problems

Characteristics of Minimum-Wage Workers

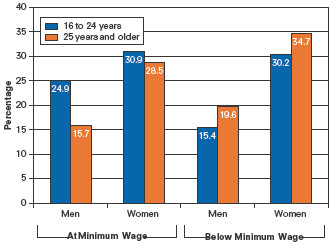

Figure 9.3 Percentage of workers earning minimum wage or below, by gender and age, 2013

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014d.

NOTE: Due to rounding, these percentages do not add up to 100%.

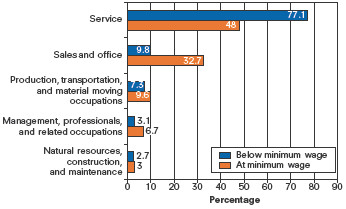

Figure 9.4 Percentage of workers earning minimum wage or below, by occupation, 2013

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014d.

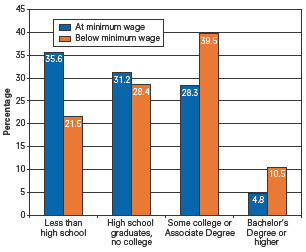

Figure 9.5 Percentage of workers earning minimum wage or below, by educational attainment, 2013

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014d.

What Do You Think?

For 2013, 3.3 million workers earned wages at or below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

The probability of earning minimum wage or lower varies by your social characteristics. Figures 9.3 to 9.5 present data on the percentage of minimum wage workers by gender, occupation, and educational attainment.

Review the data presented in Figure 9.3. Overall, a higher percentage of women work at or below the minimum wage than men. Those 25 years or older are more likely to work at or below the minimum wage level than those 16 to 24 years of age.

Based on the data presented in Figure 9.4, which occupation has the highest rate of workers earning at or below minimum wage? Which jobs within this occupation would earn below minimum wage?

Does having some college education or a college degree decrease the likelihood of earning below minimum wage? What evidence from Figure 9.5 supports your answer?

Explain how the gendered division of labor might contribute to the minimum wage patterns presented in Figures 9.3 and 9.4.

Minimum Wage

One way the United States addresses economic inequality is through the federal minimum wage. A three-step wage increase was passed by Congress in 2007, when the minimum hourly wage was $5.15. The current federal minimum wage is $7.25. However, when adjusted for inflation, the current federal minimum is still less than the minimum wage from 1961 to 1981 (Filion 2009). Most states have a minimum wage above the federal minimum.

While the minimum wage raises the wages of low-income workers in general, many low-income families continue to move in and out of poverty. Data indicate that low-wage or poverty-level workers are likely to be minority, female, non-college-educated, and nonunion, working in low-end sales and service occupations (Bernstein 1997; Bernstein, Hartmann, and Schmitt 1999; Mishel, Bernstein, and Shierholz 2009; U.S. Department of Labor 2002).

In her 2001 book Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, Barbara Ehrenreich explored life and work on minimum wage in three states: Florida, Maine, and Minnesota. Working as a hotel maid, a nursing home aide, a sales clerk, a waitress, and a cleaning woman, Ehrenreich rated her work performance as a B or maybe even a B+. In each new job, Ehrenreich had to master new terms, new skills, and new tools (and not as quickly as she thought she would be able to master them). How did Ehrenreich survive on minimum wage? She discovered that she needed to work two jobs or seven days a week to achieve a “decent fit” between her income and her expenses. She describes getting her meals down to a “science”: chopped meat, beans, cheese, and noodles when she had a kitchen in which to cook; if not, fast food at about $9 per day. For housing, she shuffled between motel rooms and apartments, moving to a trailer park at one point. Ehrenreich (2001) concluded,

Something is wrong, very wrong, when a single person in good health, a person who in addition possesses a working car, can barely support herself by the sweat of her brow. You don’t need a degree in economics to see that wages are too low and rents too high. (p. 199)

A Hazardous and Stressful Workplace

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2014e), there were 4,405 fatal work injuries in 2013. The majority of fatalities occurred in men, mostly caused by the type of work they do. The private construction industry had the highest number of fatal occupational injuries, about 18% in 2013. Highway or transportation incidents are the most common cause of fatal work injuries (about 40%). Workplace violence—including assaults and suicides—accounted for 17% of all work-related fatal occupational injuries in 2013.

In the same year, a total of 3.0 million nonfatal injuries and illnesses were reported in private industry workplaces, a rate of about 3.4 cases per 100 full-time workers (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013b). Approximately 2.8 million were injuries, the most occurring in the service-providing industries (trade, transportation, and utilities). The goods-producing industries had the largest share of occupational illnesses, about 34.3%. The U.S. Department of Labor monitors illnesses such as skin diseases, respiratory conditions, and poisonings. New reported workplace illnesses were related directly to work activity, such as contact dermatitis or carpal tunnel syndrome. Some conditions, such as long-term illnesses related to exposure to carcinogens, are usually underreported and not adequately recognized (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2009).

The 2010 explosions at the Upper Big Branch Mine in West Virginia and the Deepwater Horizon oil platform in the Mississippi River Delta heightened concerns about the safety of industrial workers. In West Virginia, 29 were killed in an explosion in the country’s worst mine disaster in 40 years. These incidents led to an ongoing reevaluation of mine regulation, employee training, and safety and the development of emergency response teams, along with improvements in underground communications technology. Coal mining is an inherently dangerous occupation, with deaths and injuries having been documented worldwide. China and Russia have the largest number of coal mine fatalities annually. The Deepwater Horizon explosion resulted in the deaths of 11 operators and is the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion resulted in the deaths of 11 workers and led to the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history.

U.S. Coast Guard

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (2003) defines job stress as the harmful emotional or physical response that occurs when a job’s characteristics do not match the capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker. Certain job conditions are likely to lead to job stress: a heavy workload, little sense of worker control, a poor social environment, uncertain job expectations, or job insecurity. Eventually, job stress can lead to illness, injury, or job failure. Studies have analyzed the impact of stress on our physical health, noting the relationship of stress to sleep disturbances, ulcers, headaches, or strained relationships with family or friends. Recent evidence suggests that stress also plays a role in chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, and psychological disorders (NIOSH 2003).

Taking a World View

Mexico’s Maquiladoras

Maquiladoras are textile, electronics, furniture, chemical, processed food, or machinery assembly factories where workers assemble imported materials for export (Abell 1999; Lindquist 2001). The maquiladora program allows imported U.S. materials to enter Mexico without tariffs; when the finished goods are sent back to the United States, the shipper pays duties only on the value added by the manufacturer in Mexico (Abell 1999; Gruben 2001). The program began in 1965 as an employment alternative for Mexican agricultural workers. Drawn to Mexico because of its proximity to U.S. borders and by low labor costs, nearly every large U.S. manufacturer has a maquiladora location. Several Asian and European companies including Sony, Sanyo, Samsung, Hitachi, and Philips also have maquiladora locations (Lindquist 2001). There are an estimated 5,000 export manufacturers along Mexico’s border with the United States, employing over 1.3 million workers (Bacon 2011). The maquiladora program has been described as the engine of growth in Mexico (Mollick and Ibarra-Salazar 2013).

The maquiladora program became controversial as soon as it appeared (Gruben 2001). Supporters of the maquiladora program argue that if these plants had not located in Mexico, they would have gone to other low-wage countries. Opponents argue that the program helped U.S. firms and others take advantage of the low-wage Mexican labor force. The maquiladoras have been criticized for their treatment of female workers, dangerous work conditions, and impact on the physical and social environment of border towns.

Most maquiladora workers are women. Yolanda is a worker from Piedras Negras.

As the sun rises, Yolanda is already awake and working—carrying water from a nearby well, cooking breakfast over an open fire, and cleaning the one-room home that she and her husband built out of cardboard, wood, and tin. She puts on her blue company jacket and boards the school bus that will take her and her neighbors across Piedras Negras to a large assembly plant. Yolanda and 800 coworkers each earn US$25 to US$35 a week for 48 hours’ work, sewing clothing for a New York–based corporation that subcontracts for Eddie Bauer, Joe Boxer, and other U.S. brands. These wages will buy less than half of their families’ basic needs (Abell 1999:595).

Yolanda’s job provides a wage, but it is not adequate to support her or her family. The daily salary for maquiladora women is about $4.67, described not as a standard of living but, rather, as a standard for survival (Moffatt 2005). According to Elizabeth Fussell (2000), early maquiladora factories attracted the “elite” of the Mexican female labor force: young, childless, educated women. Current maquiladora laborers are likely to be the least-skilled Mexican women: slightly older, poorly educated women with young children (Fussell 2000).

Yolanda’s town of Piedras Negras is no different from other maquiladora towns such as Tijuana and Matamoros. Once-quaint border towns have been transformed by maquiladora activity. Despite their profits, companies do not invest in the physical and social infrastructure of these border towns. As a result, most factory neighborhoods lack basic health and public services such as clean drinking water or sewage systems, electricity, schools, health facilities, and adequate housing (Abell 1999).

Sexual harassment is often used as a method of intimidation in the maquiladora. Supervisors taunt female workers and proposition them by offering lighter workloads in exchange for dates and sexual favors. Supervisors have also sexually assaulted female workers. Women, on and off their jobs, are subject to intimidation and violence (Moffatt 2005). As noted by Joanna Swanger (2007), female factory workers are subject to a deep and violent sexism, a culture that regards them as little more than prostitutes.

Under the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), tariff breaks formerly limited to all imported parts, supplies, and equipment used by Mexican maquiladoras now also apply to manufacturers in Canada and the United States (Lindquist 2001). During the recent national debate about immigration, NAFTA and the maquiladora program were blamed for failing to improve Mexico’s economic and business infrastructure and thus failing to reduce illegal immigration in the United States.

In Focus

Sweatshop Labor

According to Sweatshop Watch (2003), there is no legal definition of a “sweatshop.” The General Accounting Office (1994) defines a sweatshop as a workplace that violates more than one federal or state labor law. The term has come to include exploitation of workers, for example, with no livable wages or benefits, poor and hazardous working conditions, and possible verbal or physical abuse (Sweatshop Watch 2003); employers who fail to treat workers with dignity and violate basic human rights (Co-op America 2003); and businesses that violate wage or child labor laws and safety or health regulations (Foo 1994). The term sweatshop was first used in the 19th century to describe a subcontracting system in which the contractors earned profits from the margin between the amount they received for a contract and the amount paid to their workers. The margin was “sweated” from the workers because they received minimal wages for long hours in unsafe working conditions (Sweatshop Watch 2003).

Jill Esbenshade (2008) describes the networks of production that promote sweatshops and labor exploitation. She identifies how a single company, like Gap or Levi’s, relies on manufacturing in dozens of countries on four or five continents supported by an extensive competitive network of agents, factories, and small subcontractors. This type of production arrangement severs the legal liability of the brand-name companies from the workers who make their products. For example, in 2012, Apple was scrutinized for poor working conditions among iPad production workers in China. Esbenshade (2008) explains, “For garment workers this means they have little leverage in the production system, and in general have not been able to successfully organize to change their conditions. Garment factories, with little capital investment, close down and move on when confronted with an organized and demanding labor force” (p. 457). Clothing and other lightly manufactured products sold in the United States are made in more than 100 countries (International Labor Rights Forum 2011).

Though there is no legal definiton of a sweatshop, the term has come to refer to the exploitation of workers with no livable wages or benefits, working in poor or hazardous working conditions.

© EdStock/iStock

All U.S. manufacturers must follow the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which establishes federal minimum wage, overtime, child labor, and industrial homework standards. The Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division makes routine enforcement sweeps in major garment centers, fining businesses that are in violation of the FLSA. Globally, antisweatshop activists have increased regulatory and monitoring systems in producing countries and have pressured contractors to improve working conditions and to recognize unions (Esbenshade 2008).

Community, Policy, and Social Action

Federal Policies

When President William Howard Taft signed Public Law 426-62 in March 1913, he created the U.S. Department of Labor. From the beginning, the department was intended to foster and promote the welfare of U.S. wage earners, to improve working conditions, and to advance opportunities for profitable employment. In its current mission statement, the department includes improving working conditions, advancing opportunities for profitable employment, protecting retirement and health care benefits, helping employers find workers, and strengthening collective bargaining as part of its charge. The department administers and enforces more than 180 federal laws that regulate workplace activities for about 10 million employers and 125 million workers.

In addition to the FLSA, the Department of Labor enforces several statutes applicable to most workplaces. It regulates the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (pension and welfare benefit plans), the Occupational Safety and Health Act (ensuring work and a workplace free from serious hazards), the Family and Medical Leave Act (granting eligible employees as many as 12 weeks of unpaid leave for family care or medical leave), and several acts that cover workers’ compensation for illness, disability, or death resulting from work performance.

There have been two legislative responses to the labor market and income consequences of the recent recession. In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was signed into law. ARRA was a stimulus package that allowed for benefit increases and tax cuts for households, along with federal investments in infrastructure and technology. A second stimulus package, the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act, was signed into law in 2010. This package extended temporary income and payroll tax cuts and provided additional funding for emergency unemployment compensation. The nation’s long-term recovery after the recession was a primary focus of the 2012 presidential election.

Two labor issues continue to be debated in Congress. The first is raising the minimum wage. In 2001, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts and Representative David Bonior of Michigan, both Democrats, introduced legislation that proposed a $1.50 raise in the minimum wage over three years. Efforts to increase the minimum wage are supported by unions and poverty organizations, which argue that doing so will help the nation’s working poor and low-income families. Opponents, who include members of the business community and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, argue that increasing the minimum wage would put an unnecessary stress on medium-size and small businesses but would not decrease poverty. Some predict that businesses would be forced to eliminate jobs, reduce work hours, or close altogether. Results from policy analyses and academic research have not provided conclusive evidence for either argument (Information for Decision Making 2000). In 2007, the U.S. Congress passed legislation that would increase the minimum wage to $7.25 over two years.

The second issue involves protection against workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) was established in 1964 by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. The EEOC monitors and enforces several federal statutes regarding employment discrimination based on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (race, color, gender, national origin, or religion), the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (1967), the Vocational Rehabilitation Act (1973), and the Americans With Disabilities Act (1990). The EEOC (2013) has received between 95,000 and 99,000 charges of employment discrimination annually since 2008.

The Employment Non-Discrimination Act, which prohibits employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, has been introduced in every Congress (except the 109th) since 1994. The bill has yet to pass. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have passed laws prohibiting employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and 32 states and Washington, DC, also prohibit discrimination based on gender identity (Human Rights Campaign 2015). In 2015, President Obama’s executive order prohibiting workplace discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity by all federal contractors went into effect.

Trendy Clothes Are Cheaper Than Ever. Why?

Job Market Relief in 2014

The Living Wage Movement

The term “living wage” was first used in the 1800s, as labor activists argued that employers should pay employees wages high enough to support themselves and a family. More recently, living wages have been promoted as a policy tool to address economic and social inequality (Luce 2012). Maryland became the first state to require a living wage, effective October 2007. For 2011, Maryland employers with state contracts were required to pay workers a minimum of $12.49 an hour in the Baltimore-Washington areas and $9.39 an hour in rural counties (Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation 2011). States, unwilling to wait for congressional action on a federal minimum wage increase, have passed higher minimum wage laws during the past decade (Uchitelle 2006). Between 2004 and 2006, 25 states increased their minimum wage. City and county governments have done the same. Seattle residents voted to increase the city’s minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2018. Mayors in Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco were also promoting higher minimum wages for their residents. Currently there are living wage ordinances in over 140 cities, counties, and universities.

Though opponents claim that higher living wages will hurt the local economy, research has not confirmed these negative consequences. Based on scholarly research and city program evaluation, there is no evidence of increased costs for city contracts (and higher taxes for city residents) or a decrease in the number of firms bidding on contracts as a result of living wage ordinances. Additionally, none of the existing studies documented employment loss (Luce 2012).

What has been consistently noted is how the living wage increases worker’s wages. Based on a study of Boston workers, the living wage ordinance raised earnings by $6,950 per year, from $21,770 to $28,720, for workers who stayed with the same employer before and after the ordinance. Stephanie Luce (2012:19) argues,

The ordinances are not always enough to raise workers out of poverty, and still do not reach enough workers. They are difficult to enforce and, in fact, have been repealed or blocked in some cities. Where implementation is more successful, it requires constant effort by workers or worker organizations to monitor employers and the city.

In his 2014 State of the Union address, President Obama endorsed a $10.10 national minimum wage. He later signed an executive order to raise the minimum wage for individuals working on new federal service contracts to $10.10 per hour. There are living wage campaigns in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan.

Voices in the Community

Judy Wicks

Businesses have also found a way to give back to their communities, to combine their work with their social activism. Judy Wicks accomplished this as the owner of Philadelphia’s White Dog Café between 1983 and 2009. In an interview with Maryann Gorman (2001), Wicks examined how her business and activist philosophies merged at the White Dog:

Judy Wicks successfully combined her business, the White Dog Café, with her social and political activism.

RON CORTES/KRT/Newscom

A person could go to the White Dog Café just to eat. Many customers do—at least for the first time. . . . But many of the diners who come just for the food end up staying for the activism. Wicks tells of a salesman who sold the restaurant its insurance, then attended a Table Talk on the School of the Americas and became a regular at the annual protests held at the School. Wicks jokes, “I use food to lure innocent customers into social activism.”

The Dog offers diners an array of learning experiences in lecture or hands-on formats as well as field trips to other countries. There are Table Talks on a variety of topics: the American war on drugs, the Supreme Court’s decision in the 2000 election, racism. And the White Dog often organizes rides to rallies and marches, like the demonstrations against Clinton’s impeachment that Jesse Jackson called for, the Million Mom March, Stand for Children and more....

Wicks’ White Dog venture began when she sensed the dissonance between her profession and her activism. Her energies drained by splitting her values into the commercial and nonprofit worlds, she sought a simpler solution, which first led her to managing someone else’s restaurant. “I realized with the nonprofit and the for-profit that in order to really be effective, I needed to focus on one organization,” Wicks says. “So I eventually abandoned the publishing work and focused on the restaurant. But it wasn’t all my restaurant, and when I started experimenting with bringing my values to work, like having a breakfast for Salvadoran refugees, I had to part ways with my partner there. This idea of compartmentalizing your life, and having certain values in one area and other values in another, has never worked for me.”

The first step, Wicks says, was simply to change her life so that she lived where she worked. “I think that society teach[es] us, ‘Separate work from home; don’t mix them together. That’ll be too stressful.’ And I’ve always worked against that.” So the White Dog, located in a block of row houses near the University of Pennsylvania, became both her home and her business. “I’m kind of a holistic person,” she says. “I live where I work. I live ‘above the shop,’ in the old-fashioned way of doing business.” . . .

Not only does she not have to commute, . . . but she doesn’t have to go food shopping or do the dishes. “But it’s more than that,” she says, “It’s about energy and focus. And relationships. Being able to foster all these relationships.”

The relationships she speaks of are those with her staff. One of the White Dog’s missions is “Service to Each Other,” an in-house goal of creating a tolerant and fair workplace. . . . Moving past standard business boundaries in this way has informed Wicks’ creative development of the White Dog’s missions. From encouraging her employees to re-create their job descriptions to fostering a sense of community among other Philadelphia restaurants, Wicks has shown that profitable businesses don’t have to be stark-raving competitive.

In 2009, Wicks sold the White Dog Café to allow her to focus full-time on her social and humanitarian efforts. In 2001, Wicks cofounded the national organization Business Alliance for Local Living Economies. The organization brings together more than 22,000 independent U.S. and Canadian businesses to build economies that are community-based, green, and fair (Business Alliance for Local Living Economies 2012).

SOURCE: Gorman, Maryann. 2001. “The White Dog’s Tale” YES! Magazine, Spring 2001. Reprinted from YES! Magazine, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110. Subscriptions: 800/937-4451. Web: www.yesmagazine.org

Worker-Friendly Businesses—Conducting Business a Different Way

Each year Fortune magazine releases a list of the “100 Best Companies to Work For.” For 2007, the magazine wrote,

Ten years ago, when we began compiling this list, the idea that your employer would deliver your groceries (a new perk at Microsoft) or allow you to do your laundry at work (Google) might have seemed crazy. . . . Indeed, much has changed in the American workplace over the past decade. (Levering and Moskowitz 2007:94)

No. 1 on Fortune’s 2014 list was Google. This employer features 30 free gourmet cafeterias in its Mountain View, California, headquarters. But Google was named number one for more than its food. This business rewards its 46,000 employees with benefits that include competitive salaries and stock options, on-site laundry and dry-cleaning, outdoor and indoor recreational facilities, a community-supported fishery program, and a generous parental leave program (22 weeks for new mothers and 12 weeks for new fathers).

There is no big secret to creating worker-friendly organizations, although some organizations are slow to learn their values. Beyond the standard employee benefit package of vacations, health care, retirement plans, and life insurance, innovative employers have used dependent care, flexible work options, expanded leave time, and enhanced traditional benefits to attract and retain employees. As a result, these employers have reduced employee turnover, increased employee satisfaction, and improved worker productivity (Schmidt and Duenas 2002).

Flexible work hours help facilitate an employee’s work–life balance, especially for women (C. Sullivan and Lewis 2001). Female employees can change their schedules to take children to school, be home when children return from school, or attend special school events (McDonald et al. 2005). Flexible work hours also permit employees to manage other personal matters. Employees who choose to work nonstandard hours or to work remotely may increase their production due to less distractions or creating an environment that optimizes their creativity and work flow (Shockley and Allen 2012).

Organized and Fighting Back

Historically, labor unions have served as bargaining agents for workers, fighting for fair wages, safe work environments, and benefits from employers. Many of the worker benefits advocated by early labor unions are now mandated through federal, state, or local labor laws. In our changing and global economy, unions cannot sustain themselves by simply negotiating pay, benefits, and working rights. To remain vital and relevant, unions need to develop multilevel strategies and use new skills (Lazes and Savage 2000). In 1983, the first year when union membership data were available, the rate of membership was 20.1%, accounting for 17.7 million union members. For 2012, the rate of membership was 11.2%, with a total of 14.5 million members (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014f).

Following years of declining membership, U.S. unions shifted their membership strategy (Fantasia and Voss 2004). Changing their focus from the declining U.S. manufacturing sector, union organizers began to successfully rebuild their membership in the service and public sectors dominated by female, immigrant, and minority workers. During 2012, membership in the manufacturing industries was 10.5%, while employees in the utilities industry had the highest rate of membership, 25.6% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014f). Unions are presented as organizational vehicles of social solidarity, “emphasizing direct [worker] action as an important source of collective power” (Fantasia and Voss 2004:128). In addition, these unions have a strong orientation toward social justice that appeals to their new members, connecting the labor movement with the movement for social citizenship and universal civil rights (Fantasia and Voss 2004) and encouraging broad-based movement building and worker self-organization (Avendaño and Hiatt 2012).

In recent years, innovative collaborations have been forged. Unions have collaborated with other types of social movements to better support workers and their families. Nonunion social movements include worker advocacy groups representing women, immigrants, racial and ethnic groups, and working families. Living-wage campaigns and worker centers have also been part of the effort to increase worker power (Kalleberg 2011).

One example of union innovation is the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees (UNITE). In 1996, it launched a “Stop Sweatshops” campaign linking union, consumer, student, civil rights, and women’s groups in the fight against sweatshops. UNITE helped form United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) in 1997, bringing together a coalition of student groups to raise awareness about the problem of sweatshop labor in the manufacturing of collegiate clothing (caps, shirts, and sweatshirts sold in campus stores). In March 1998, Duke University adopted the nation’s first code of conduct for university trademark licensees. Under the code, any clothing with the Duke logo would be subject to labor and human rights standards. The student group Duke Students Against Sweatshops played a key role in shaping the antisweatshop code (Sweatshop Watch 2000). In 2004, UNITE announced that it was merging with the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union. The new union, called UNITE HERE (2012), represents workers in the hotel, gaming, food service, manufacturing, textile, distribution, laundry, and airport industries.

Also working with USAS is the Student Labor Action Project (SLAP). This campus-based coalition supports the growing economic justice movement among college students by “making links between campus and community organizing, providing skills training to build lasting student organizations, and developing campaigns that win concrete victories for working families” (Student Labor Action Project 2007). The organization sponsors a national student labor week of action each year, highlighting issues such as the DREAM Act, fair contracts for campus employees, environmental and workforce sustainability, and living wages. In recent years, SLAP has also organized against educational cuts in state budgets and increasing tuition.

Voices of Young Workers

Sociology at Work

law

Stacey Stone Semmler—Class of 2006

Undergraduate Majors: Sociology, Political Science

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor says that being a lawyer is one of the best jobs in the world, because “every lawyer, no matter whom they represent, is trying to help someone.... To me, lawyering is the height of service” (quoted in Campos 2013).

Earning a juris doctor (JD) degree usually takes seven years of full-time study—completing an undergraduate degree followed by three years of law school. Most states require practicing lawyers to earn their degree at an American Bar Association (ABA) accredited program. There are more than 200 accredited law schools in the United States; the majority of schools require applicants to take the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). In the second and third year of law school, students can customize their coursework for a particular area of law practice. There are many major areas of law practice, including bankruptcy, business, civil rights, criminal, environment, family, labor and tax law. In order to practice, one must successfully complete licensure, also referred to as a state bar exam.

Stacey Stone Semmler practices civil litigation in a variety of fields, including insurance defense, commercial debt collection, election and campaign finance law, and construction and workers’ compensation defense. Her undergraduate internship at Girl Scouts Beyond Bars inspired her career and served as an important experience:

Stacey Stone Semmler

Courtesy of Stacey Stone Semmler

That opportunity demonstrated to me that the law has power. It truly motivated me to attend law school. I gained so much experience in interacting with a variety of people and personalities from a variety of ethnic backgrounds and social classes. My current job is not necessarily directly related to my work with Girl Scouts; however, each time I interviewed for a job, that experience was discussed.

Sociology is still part of her work, especially during a trial.

In my field we often have to consider the perception, especially when representing a corporation. If we have multiple lawyers, will it look bad? If we have too much technology, does it look like the poor opposing party is just being outspent? There are numerous things to consider. It also is beneficial when picking a jury. You have to consider your client and how he/she will be judged by the person who sits before you on a panel based on things such as their race, social class, job position, relationships, and community involvement.

Chapter Review

- 9.1 Describe the transition from agricultural to industrial production

During the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, the means of production shifted from agricultural to industrial. In agrarian societies, economic production was very simple, based primarily on family agriculture and hunting or gathering activities. During the Industrial Revolution, an economic shift occurred in how people worked and how they earned a living. Family production was replaced with market production, in which capitalist owners paid workers wages to produce goods.

- 9.2 Compare how the sociological perspectives explain social problems related to work

According to the functionalist perspective, work serves specific functions in society. Our work provides us with some predictability about our life experiences. Conflict theorists argue that capitalist and corporate leaders maintain their power and economic advantage at the expense of their workers and the general public. From a feminist perspective, work is a gendered institution. Men’s and women’s identities as workers are created, reproduced, and then solidified in the everyday routines of informal work groups and formal workers’ organizations. According to symbolic interactionists, we attach labels and meanings to an individual’s work. These social constructs create an order to our work and our lives but can also create social problems.

- 9.3 Explain the difference between unemployment and underemployment

While unemployment is defined as the number of individuals who are looking for a job, underemployment is the number of employed individuals who are working in a job that underpays them, is not equal to their skill level, or involves fewer working hours than they would prefer. Both are measured by the U.S. Department of Labor.

- 9.4 Identify which forms of discrimination workers are protected against

U.S. workers are protected against discrimination based on race, color, gender, national origin, religion, age, and disabilities. Though states have passed laws prohibiting employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, there is no federal law in place.

- 9.5 Identify how labor unions have changed their membership strategy

Union organizers have rebuilt their membership in the service and public sectors dominated by female, immigrant, and minority workers. These unions have a strong orientation toward social justice that appeals to new members, connecting the labor movement with the movement for social citizenship and universal civil rights and encouraging broad-based movement building and worker self-organization. Student groups have provided strong support for unions and living wage organizations on college campuses.

Key Terms

- deindustrialization, 243

- Industrial Revolution, 242

- scientific management, 246

- service revolution, 242

- sweatshop, 260

- underemployment, 253

Study Questions

- Which population of workers has changed the U.S. workplace the most—women or foreign-born workers? Explain the reason for your answer.

- Using a coffee barista as an example, identify and explain Karl Marx’s theory of worker alienation.

- Why and how are women disadvantaged in the workforce—in both the types of jobs they occupy and their salary level?

- Identify the positive and negative consequences of globalization.

- From a functionalist and conflict perspective, examine the role of a contingent workforce in the U.S. economy.

- Why have labor unions declined in membership? How can labor unions expand their appeal and membership to workers, and how can they do this during the economic recession?

- Human trafficking includes the involuntary movement of individuals within one country or from one country to another for exploitation. Exploitation may include physical labor or sexual exploitation (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Anti–Human Trafficking Unit 2006). In 2012, the United Nations reported that 2.4 million people are victims of human trafficking at any one time, with the majority being exploited as sexual slaves (Lederer 2012). The United States is reported to be a frequent destination country where victims are brought to be exploited, yet not much is discussed about our country’s role in human trafficking. Is trafficking a U.S. social problem? Why or why not?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.