Chapter 8 Education

Learning Objectives

- 8.1 Compare how the sociological perspectives examine the social problems related to education

- 8.2 Explain the process of educational tracking

- 8.3 Describe the educational inequalities related to social class, gender, and race and ethnicity

- 8.4 Summarize the history of U.S. educational reform

- 8.5 Assess whether school choice has improved educational outcomes

Education is assumed to be the great equalizer in our society. There are inspirational stories of women and men who, after a tough childhood or adulthood, complete their education, become successful members of society, and are held as role models. Education is presented as an essential part of their success, serving as a cure for personal or situational shortcomings. If you are poor, education can make you rich. If your childhood was less than perfect, a college degree can make up for it. On the occasion of launching the Head Start program in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson is quoted as saying, “If it weren’t for education, I’d still be looking at the southern end of a northbound mule” (Zigler and Muenchow 1992).

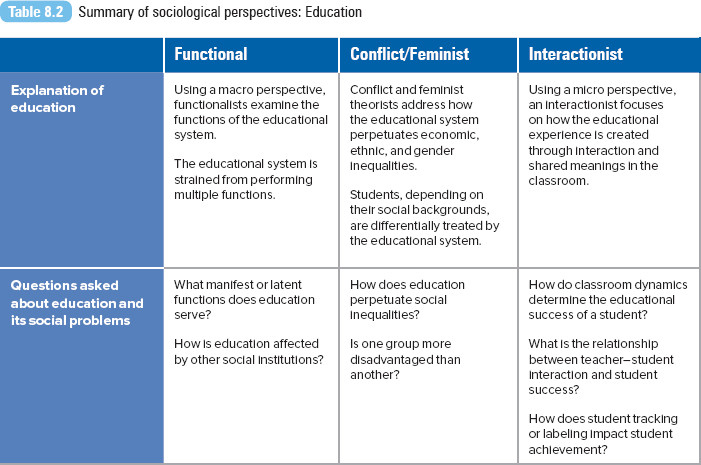

Yet along with these images of success, we are bombarded with images of failure. Media coverage and political rhetoric highlight problems with our educational system, particularly with our public schools. In recent state and national political campaigns, the quality of teaching and the preparation of teachers were scrutinized, and school districts with low scores on standardized exams were criticized. U.S. students are said to be falling behind the accelerated pace of higher education internationally. Though 43% of 25- to 64-year-old Americans have earned an associate’s degree or higher, there are several industrial countries with higher rates of college attainment (refer to Figure 8.1). Additionally, the increase in the proportion of the population with a college degree is lower in the United States (a 7% increase between 2000 and 2012) in comparison with other industrialized countries (an average of 11% over the same time period) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2014). In 2006, a panel of education, labor, and public policy experts, including two former education secretaries, warned that if the United States does not keep pace with the educational gains made in other countries, our standard of living will be seriously compromised. During his first year in office, President Barack Obama set a goal for the United States to have the highest proportion of college students in the world.

Figure 8.1 Percentage of adults 25–64 years of age with an associate’s degree or higher, 2012 (only countries 40% or higher reported)

SOURCE: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2014.

So which is it: is education a key to individual success or an institutional failure? In this chapter, we’ll first examine this question by reviewing our educational system from different sociological perspectives. Then we’ll explore current social problems in education, along with policy and program responses.

The New Educational Standard

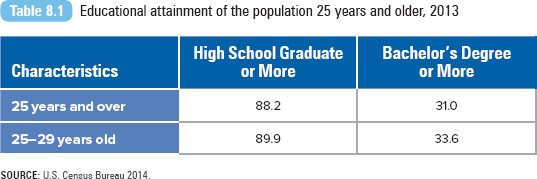

We tend to define a high school degree as the educational standard of the past, now replaced with a bachelor’s degree. Actually, data from the U.S. Census Bureau confirm that the United States is acquiring an increasingly more educated population (see Table 8.1 and U.S. Data Map 8.1).

For 2013, the U.S. Census Bureau (2014) reported that 88.2% of adults (25 years and older) had completed at least a high school degree, and more than 31% of all adults had attained at least a bachelor’s degree. Educational attainment levels of adults will continue to rise as younger, more educated age groups replace older, less educated ones.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2014.

International Student Acheivement

College Education Race

Exploring social problems

Educational Attainment in the United States

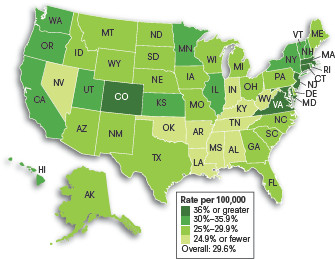

U.S. Data Map 8.1 Percentage of adult population 25 years and older with a bachelor’s degree or more by state, 2013

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2013.

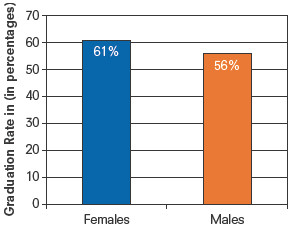

Figure 8.2 2006 graduation rates by gender

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2013.

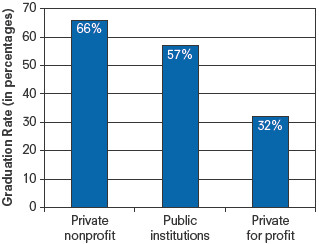

Figure 8.3 2006 graduation rates by institution type

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2013.

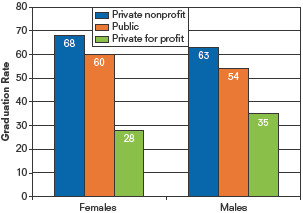

Figure 8.4 2006 graduation rates by gender and institution type

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2013.

What Do You Think?

The 1990 Student Right-to-Know and Campus Security Act requires all schools to publish their graduate rates—the percentage of students that complete their program within 150% of the normal time for completion, which is six years for students enrolled in four-year bachelor’s degree program. Students who transfer and complete their degree in another school are not counted as completers in these data.

Populations in the Northeast had the highest proportions with a bachelor’s degree or higher. The state with the highest proportion was Massachusetts (40.3%). West Virginia had the lowest proportion (18.9%). What is the proportion for your state?

Graduation rates vary by gender (Figure 8.2) and type of institution (Figure 8.3). Females have higher graduation rates than males in public and private nonprofit institutions (Figure 8.4).

Contact your institutional research office about your school’s graduation rates since 2000. How does your school compare with other schools in your state?

Sociological Perspectives on Education

Functionalist Perspective

The institution of education has a set of manifest and latent functions. Manifest functions are intended goals or consequences of the activities within an institution. Education’s primary manifest function should come as no surprise: it is to educate! The other manifest functions include socialization, personal development, and employment. Our educational system ensures that each of us will be appropriately socialized and adequately educated to become a contributing member of society (and the labor force). As Nicola Ansell (2008) writes, “Educational systems view children as ‘human becomings’ that they are explicitly preparing for work” (p. 808). We learn skills and knowledge, as well as about society’s norms, values, and beliefs, which are necessary for our survival and, ultimately, the society’s survival.

Education’s latent functions may be less obvious. One unintended function that education serves is as a public babysitter. No other institution can claim such a monopoly over the total number of hours, months, and years of a child’s life. From kindergarten through high school, parents can rely on teachers, administrators, and counselors for their child’s education and for supervision, socialization, and discipline. In addition, education controls the entry of young women and men into the labor force and the timing of that entry. Consider the surge in employment rates after high school and college graduation. There is always a rush to get a job each summer; employers rely on the temporary labor of high school and college students during busy summer months. Finally, education establishes and protects social networks by ensuring that individuals with similar backgrounds, education, and interests are able to form friendships, partnerships, or romantic bonds.

Functionalists argue that education has been assigned so many additional tasks that it struggles in its primary task to educate the young. In addition to its own main functions, our educational system has taken over functions of other institutions. For example, the educational system provides services to students with family problems, emotional needs, or physical challenges. Schools also provide services for parents in the form of adult education or parenting classes.

Conflict Perspective

Conflict theorists do not see education as an equalizer; rather, they consider education a “divider”—dividing the haves from the have-nots in our society. Conflict theorists focus on the social and economic inequalities inherent in our educational system and on how the system perpetuates these inequalities.

Conflict theorists highlight the socialization function of education as part of the indoctrination of Western bureaucratic ideology. The popular posters and books on “what I learned in kindergarten” could serve as the official list of adult life rules: share everything, play fair, and put things back where you found them. Never mind kindergarten—the indoctrination can begin as early as nursery school. Rosabeth Moss Kanter (1972) describes a child’s experience in nursery school as an “organizational experience” creating an organizational child. Carefully instructed and supervised by their teachers, students are guided through their day in ordered agendas; they are rewarded for conformity, and any signs of individuality are discouraged. The organizational child is sufficiently prepared for the demands and constraints of a bureaucratic adult world.

Although we consider education the primary method of achieving equality and mobility in our society, conflict theorists argue that it actually sustains the structure of inequality. As Martin Marger (2008) explains, the relationship between education and socioeconomic status operates in a cycle perpetuated from one generation to the next. It begins with high-income and high-status parents who can ensure a greater amount and greater quality of education for their children. Pierre Bourdieu (1977) argues that children from upper- and middle-class families are advantaged in our educational system due to their possession of cultural capital, linguistic and cultural competence, and familiarity with culture that is passed on by their parents and their social position. Children whose parents introduce them to a culture consistent with the class-based assumptions of education are more likely to succeed than those whose parents do not (Lareau 2003).

But there is another form of capital to consider. Social capital refers to investments in social relationships and networks (Lin 2011) and is also distributed unequally by social class. Young children who are more engaged in extracurricular activities and have increased opportunities to build personal relationships with adults outside their immediate family demonstrate greater academic progress than children who lack access to these activities or opportunities (Freeman and Condron 2011).

Jonathan Kozol, in his classic studies Savage Inequalities: Children in America’s Schools (1991) and The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America (2005), presents a discouraging portrait of student learning in inner-city schools that are understaffed, undersupplied, and in disrepair. This educational inequality is created by public school systems that rely on property taxes to finance school staffing and operations. As a result, a caste system has emerged in our educational system. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, de facto school segregation still exists. Income and residential segregation have led to greater differentiation in school quality and opportunities between rich and poor neighborhoods (Reardon 2011).

From a conflict perspective, we do not invest the same amount of public spending, political interest, or public attention in the educational achievement of students from lower social classes compared to students from middle or upper classes.

© J A Giordano/CORBIS SABA

The gap between the haves and the have-nots is so wide it seems impossible to attain educational equity. As Kozol (1991) observes,

children in one set of schools are educated to be governors; children in another set of schools are trained to be governed. The former are given the imaginative range to mobilize ideas for economic growth; the latter are provided with the discipline to do the narrow tasks the first group will prescribe. (p. 176)

Kozol introduces us to 8-year-old Alliyah. At the time, the New York City Board of Education spent $8,000 for her education in a public school in the Bronx. She would have received a public education worth $12,000 had she been educated in a typical White suburb of New York, and $18,000 if she had resided in a wealthy White suburb. According to Kozol (2005), what society chooses to spend on lower-class neighborhoods and schools “surely tells us something about what we think these kids are worth to us in human terms and in the contributions they may someday make to our society” (p. 44).

Growing Segregation

Feminist Perspective

Inequalities are based not just on social class but also on gender. Research reveals the persistent replication of gender relations in schools, evidenced by the privileging of males, their voices, and their activities in the classroom, on the playground, and in hallways (D. E. Smith 2000).

One of my favorite illustrations of the privilege given to a male voice comes from my own discipline. In sociology, there is a concept called the “definition of the situation,” which refers to the phrase “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas 1928:572). The concept is an important one to the symbolic interactionist perspective and is often attributed solely to sociologist W. I. Thomas. However, the correct attribution is to Thomas and his wife, Dorothy Swaine Thomas. R. S. Smith (1995) investigated the citation in more than 244 introductory sociology textbooks and found that most attributed the concept solely to W. I. Thomas. One reason for the omission of Swaine Thomas is that she may not have contributed to the phrase (although there is no documented evidence to support this), but R. S. Smith (1995) suggests that the omission is because of a professional and structural ideology that historically represented sociology as a “male” domain. Smith notes that the citations began to include Swaine Thomas after the mid-1970s, a time when sociology and introductory texts began to respond to and to reflect the changes brought about by a growing women’s movement and increasing numbers of female sociologists.

Gender bias and gender stereotypes work to exclude and alienate girls early in their educational experience (American Association of University Women 1992; Sadker and Sadker 1994; Sadker and Zittleman 2009). Males have favored status in education, particularly in their interactions with their teachers. In the classroom, girls are invisible, often treated as second-class educational citizens. This is how Myra and David Sadker (1994) explained the subtle yet consequential gender bias in the classrooms they visited. After observing teachers and their interactions with girls and boys in more than 100 elementary classrooms, the Sadkers found that teachers were more responsive to boys and were more likely to teach them actively. Overall, girls received less attention, whereas boys got a double dose, both negative and positive. Boys received more praise, corrections, and feedback, whereas girls received a cursory “OK” response from their teachers. Sadker and Sadker concluded that over time, the unequal distribution of teacher time and attention may take its toll on girls’ self-esteem, achievement rates, test scores, and ultimately careers. In a 2009 follow-up study, David Sadker and Karen Zittleman confirmed a reduction of classroom gender bias, but recommended that much more work needed to be done to eliminate gender bias.

For example, Sian Beilock and her colleagues examined the effects of teacher math anxiety on student math anxiety in an elementary school setting (quoted in Schmid 2010). They found that students tend to model themselves after adults of the same sex. A female teacher who is anxious about math may pass on the same concerns to her female students, reinforcing the belief that boys are better at math than girls. Though student math anxiety was not related to teacher math anxiety at the beginning of the school year, by the end of the year, the more anxious teachers were about their math skills, the more likely it was that their female students agreed that boys are good at math and girls are good at reading. Girls who agreed with this statement scored lower on math tests than boys and girls who had not developed this belief (Schmid 2010).

Structural factors along with interpersonal dynamics also contribute to the creation and maintenance of gender inequality on college and university campuses (Stombler and Yancey Martin 1994). Men and women experience college differently and have markedly different outcomes (Jacobs 1996). College women are subjected to male domination through their peer relations (Stombler and Yancey Martin 1994) in the classroom, in romantic involvements (Holland and Eisenhart 1990), and in organized activities. Even activities such as fraternity “little sister” programs, which Mindy Stombler and Patricia Yancey Martin (1994) studied, provide the structural and interpersonal dynamics necessary to create an atmosphere conducive to women’s subordination.

Interactionist Perspective

Sadker and Sadker’s 1994 study identified the differential effects of teacher communication on female and male students. The interaction between teachers and students daily reinforces the structure and inequalities of the classroom and the educational system. From this micro perspective, sociologists focus on how classroom dynamics and practices educate the perfect students and at the same time create the not-so-perfect ones. In what ways does classroom interaction educate and create?

Assessment and testing are standard practices in education. Students are routinely graded and evaluated based on their work and ability. Interactionists would argue that along with assessment comes unintended consequences. Based on test results, students may be placed in different ability or occupational tracks. In the practice called tracking, advanced learners are separated from regular learners; students are identified as college bound versus work bound.

Advocates of tracking argue that the practice increases educational effectiveness by allowing teachers to target students at their ability level (Hallinan 1994). Yet placing students in tracks has been controversial because of the presumed negative effects on some students. Opponents argue that labels such as an upper versus lower track or “special” or slow learners are used systematically to deny a group of students access to education (Ansalone 2004). In addition to creating unequal learning opportunities (Hallinan 2003), tracking may encourage teachers, parents, and others to view students differently according to their track, and as a result, their true potential may be hindered (Adams and Evans 1996). African Americans, Latinos, and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to enroll in advanced placement or honors courses (Mickelson and Everett 2008). Countries that practice ability tracking have greater educational inequity than countries who do not track their students (Schofield 2010). Although tracking is intended to aid students, it may lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy: Students will fail because they are expected to do so.

Despite the documented negative consequences of tracking, the practice continues in approximately 60% of all elementary schools and 80% of all secondary schools (Ansalone 2001). Although interactionists do not assess the appropriateness of the label, they would address how the label affects students’ identity and educational outcomes. Issues of inequality must also be addressed if the data suggest that students of particular gender or ethnic/racial categories are targeted for tracking.

A summary of all sociological perspectives on education is presented in Table 8.2.

Problems and Challenges in Education

The idea that there is a public education crisis is not a new one. A 1918 government report referred to the “erosion of family life, disappearing fathers, working mothers, the decline of religious institutions, changes in the workplace, and the millions of newly arrived immigrants” as potential sources of the public education crisis (Meier 1995:9). At the time, the government’s response was the creation of the modern school system with two tracks, one for terminal high school degrees and the other for college-bound students (Meier 1995).

The current call for educational reform was initiated during President Ronald Reagan’s administration. In 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education released its report, A Nation at Risk: The Imperatives for Educational Reform, a scathing indictment of the education system. The commission was created by Secretary of Education T. H. Bell to respond to what he called the “widespread public perception that something is seriously remiss in our educational system” (National Commission on Excellence in Education 1983:7). Claiming that we are raising a scientifically and technologically illiterate generation, the commission noted the relatively poor performance of American students in comparison with their international peers, declining standardized test scores, the weaknesses of our school programs and educators, and the lack of a skilled American workforce (National Commission on Excellence in Education 1983).

The educational reform movement marches on, gaining momentum with each elected president. At one time or another, each president after Reagan has referred to himself as the “Education President,” declaring an educational crisis and calling for change. Educators and reformers agree that this is an exciting time for American education (Ravitch and Viteritti 1997). Under George H. W. Bush’s administration, Congress passed America 2000, which was followed by the Goals 2000: Educate America Act in 1994 during Bill Clinton’s administration. Congress passed the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 under George W. Bush’s administration. All congressional acts call for coordinated improvements and sweeping reform of our educational system.

David Berliner and Bruce Biddle (1995) contend that the crisis in public education is a manufactured one, constructed by well-meaning or not-so-well–meaning politicians, educational experts, and business leaders. Berliner and Biddle don’t believe that public schools are problem free; rather, by focusing on the manufactured crisis, they believe we’re not addressing the real problems facing our schools, those based in social and economic inequalities. What is the evidence regarding these problems and challenges to our educational system? Let’s first examine the basis of education: literacy.

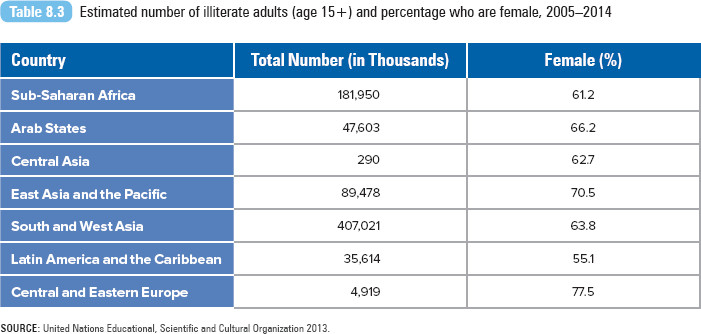

The Problem of Basic Literacy

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO 2013) estimates that there are more than 781 million illiterate adults and 126 million illiterate youth in the world. Most live in South and West Asia, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Multiple barriers restrict the achievement of widespread literacy: insufficient access to quality education, weak support for youth exiting the educational system, poorly funded and fragmented educational programs, and limited opportunities for adult learning. Literacy disparities are associated with gender, poverty, place of residence, ethnicity, language, and disabilities. Gender disparities are particularly pronounced in developing countries. Women account for 75% (UNESCO 2013) of adults worldwide who cannot read and write (refer to Table 8.3).

According to the Literacy Volunteers of America (2002), very few U.S. adults are truly illiterate, yet the United States is not a literacy superpower (ProLiteracy Worldwide 2006). What continues to be of concern is the number of adults with low literacy skills who are unable to find and retain employment, support their children’s education, and participate in their communities. Basic literacy skills, such as understanding and using information in texts (newspapers, books, a warranty form) or instructional documents (maps, job applications) or completing mathematical operations (filling out an order form, balancing a checkbook), are related to social, educational, and economic outcomes (Sum, Kirsch, and Taggart 2002).

Data from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (ProLiteracy Worldwide 2006) reveal that 30 million U.S. adults demonstrated skills at the “below basic” level (from being nonliterate in English to being able to follow written directions to fill out a form). About 63 million adults demonstrated skills at the basic level (having basic literacy skills to read and understand information in short, simple documents). A total of 43% of all Americans are estimated to be at these two levels. In contrast, 57% of Americans were categorized at the higher levels—intermediate (able to complete moderately challenging literacy tasks, e.g., refer to a reference document for information) and proficient (able to read and integrate various materials) (ProLiteracy Worldwide 2006).

The U.S. Department of Education reports that individuals at higher levels of literacy are more likely to be employed, to work more weeks per year, and to earn higher wages than are individuals with lower levels of literacy (Kirsch et al. 2002). Education increases an individual’s literacy skills, which determine educational success. Basic academic skills influence such educational outcomes as high school completion, college enrollment, persistence in college, field of study, and type of degree obtained (Sum et al. 2002).

Although the United States spends more per capita on education than other high-income countries, our literacy scores are below average in a world comparison. In 2013, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) compared literacy scores for native-born U.S. adults and residents in 22 other OECD member countries. OECD measured a set of necessary work skills related to information and communication technologies, which it labeled technology-rich environments. The literacy scores of U.S. adults ranked 16th out of 23 countries in literacy proficiency (decoding written words, interpreting and evaluating complex texts), 21st in numeracy proficiency (solving math problems), and 14th in problem solving (solving personal or work problems using a computer). The nations that scored higher were Japan, Finland, Netherlands, and Sweden. The report revealed that socioeconomic background had a stronger effect on proficiency levels in the U.S. than in other OECD countries.

Toppling Adult Illiteracy

Taking a World View

Educational Tracking and Testing in Japan

After World War II, Japan adopted a 6-3-3-4 model of education that includes six years of elementary school (shogakko), three years of junior high school (chugakko), three years of high school (kotogakko), and four years of university study. Tracking does not occur in Japanese elementary and junior high schools; instead, their educational system emphasizes effort and hard work, discounting differences in ability. No effort is made to identify below- or above-average children in the classroom. All elementary and junior high schools offer the same curriculum, regulated by the national Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT; Ansalone 2004).

However, a highly competitive form of tracking (ruikei) begins at the high school level, separating students into two distinct tracks: general high schools leading to college and vocational high schools leading to jobs. Educational leaders argue that this system is able to accommodate students’ different interests and talents and improves students’ overall performance on national entrance exams (Ansalone 2004). Entrance examinations, also known as jyuken higoku (examination hell), serve as the major sorting mechanism for Japan’s high schools and colleges (Bjork and Tsuneyoshi 2005).

Unintentionally, this tracking system has created a two-tier system of schools. Vocational high schools are students’ second choice (Ono 2001). In his analysis of vocational high schools in the city of Kobe, Thomas Rohlen (1983) reports that one vocational high school draws students from the lower third of graduating ninth graders in the city. When asked if they had had a choice, 80% of the students said they would rather have attended a general high school. Vocational high schools have developed a negative reputation for school violence, smoking, and drug abuse, and their students are considered second-class citizens (Rohlen 1983). In his comparative analysis of educational systems in Japan and the United States, George Ansalone (2004) concluded that tracking “promotes differentiation of the curricula, teacher expectations, school misconduct, race, class, gender bias, and the development of separate friendship patterns. When tracking is employed, upper-track students receive a higher quantity and quality of instruction from more qualified instructors who utilize a greater variety of instructional techniques” (p. 150).

During the last two decades of the 20th century, several significant changes have occurred in the Japanese educational system. First, government leaders and educational scholars asserted that the emphasis on entrance examinations combined with the demands on students to learn large volumes of content had actually dulled students’ interest in learning (Bjork and Tsuneyoshi 2005). Educational reforms began in the 1970s, reducing the amount of material covered by teachers, incorporating more student-centered and integrated learning in the classroom, and reducing the intensity of student learning and testing. MEXT referred to these reform policies as yutori kyoiku or reduced-intensity reforms. Response to the reforms has been mixed, with some applauding the new student-centered emphasis of the curriculum but others worrying about the impact of a “watered down” curriculum (Bjork and Tsuneyoshi 2005).

Second, admissions into Japan’s universities have become less competitive. As its population of 18-year-olds has decreased by more than half a million since 1992, Japan’s universities have had trouble recruiting students. According to Rie Mori (2002), entrance examinations were expected to identify the best students for university education, but this is no longer necessary because there are more universities to accept students who do not score well on the exams. The universalization of higher education in Japan has led to a greater number of students entering universities who are not as high achieving as students of the past. Japanese higher education must figure out how to educate students with a broader range of learning styles and abilities (Mori 2002).

How has tracking been part of your educational experience? Does tracking take place in your college?

Inequality in Educational Access and Achievement

Social Class and Education

Socioeconomic status is one of the most powerful predictors of student achievement (College Entrance Examination Board 1999). The likelihood of dropping out of high school is five times higher among students from lower-income families than among their peers in high-income families (Laird et al. 2006). Dropping out of high school is related to negative economic outcomes. For example, the 2010 median income of persons who had not completed a high school degree was $20,241. In contrast, the median income of persons who had completed at least a high school credential (e.g., general equivalency diploma) was $30,627 (U.S. Census Bureau 2012).

Students from lower-income homes or who have parents with little formal education score lower on average than students from families earning more than $100,000 per year or who have parents with a bachelor’s degree or higher. In 2013, the average critical reading SAT score was 434 for a student with a family income below $20,000 versus 522 for a student with a family income of $100,000 to $120,000. The highest average score was 565 for students with a family income greater than $200,000. For students with parental education less than a high school diploma, the average critical reading score was 423. In contrast, students with parental education of at least a bachelor’s degree had an average score of 523. For students with parental education of a graduate degree, the average critical reading score was 560 (College Board 2013).

High-income families can invest more time and resources into their children’s cognitive development than lower-income families; high-income families have greater socioeconomic and social resources that benefit their children than lower-income families; and, according to Douglas Downey, Paul von Hippel, and Beckett Broh (2004), the primary source of inequality between children of high and low socioeconomic status lies in the children’s disparate nonschool (home and neighborhood) environments. High-income families can invest more time and resources into their children’s cognitive development than lower-income families; high-income families have greater socioeconomic and social resources that benefit their children than lower-income families (Reardon 2011).

Research suggests that spending time in novel environments (not at home or at school and not being cared for by a parent or day care provider) and in particular activities (interactive play) has educational benefits. When Meredith Phillips (2011) examined the socioeconomic differences in how parents spend their time with children, she found that high-income children spend about 1,300 more hours in novel places between birth and six years of age than low-income children. For example, high-income infants and toddlers spend an additional four and a half hours per week in indoor and outdoor recreation facilities, at church, or at businesses when compared with infants and toddlers from low-income families. After children begin school, the time in novel contexts continues as high-income children and children with college-educated mothers spend three more hours per week in novel places than low-income children or children in less-educated families. Phillips hypothesizes that exposure to novel contexts is directly related to income, as families with higher incomes have more money to spend on novel-context activities and settings.

In research conducted by the Public Agenda organization (Johnson et al. 2009), the number-one reason students gave for leaving college is that they had to simultaneously balance work and school. College dropouts were less likely to report being bored or not enjoying their classes as the reason why they quit. More than half of those who left school identified the “need to work and make money” and the stress related to juggling both. Most students did not receive financial assistance from their families or from their schools. Public Agenda researchers suggest that today’s college students are not leading the stereotypical college life of balancing classes and weekend parties; instead, they are balancing classes with working to pay rent.

Remedying the Achievement Gap

In Focus

Controlling the Cost of Higher Education

A college education is still part of the American Dream. Sallie Mae, a financial service company specializing in education, annually releases a national report on how college tuition is managed by parents and their students. In the 2012 report, Sallie Mae and Ipsos (an independent marketing research company) found that 83% of college students and parents strongly agreed that higher education is an investment in the future, college is needed now more than ever (70%), and college is the path to earning more money (69%).

But the truth is that most young adults do not attend a four-year college. According to Paul Taylor and his colleagues (2011), the main barrier to higher education is financial. Among individuals 18 to 34 years old who are not in school and do not have a bachelor’s degree, about two thirds report that they are not continuing their education in order to support a family; more than half say they prefer to work and make money (Taylor et al. 2011).

In his 2012 State of the Union speech, Barack Obama called on the federal government, states, colleges, and universities to promote access and affordability in higher education. Obama proposed educational and legislative reforms tying federal campus aid to responsible tuition policies. Aiming primarily at state colleges and universities, Obama outlined financial incentives for schools to contain their tuition, enhance teaching and learning, and increase affordability and graduation rates (White House 2012).

The president’s announcement received a mixture of praise and caution from educational leaders and college groups (Field 2012). David Warren (2012), director of the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, said,

The collective challenge facing the nation is to make college more affordable, without losing our position of having the best higher education system in the world. . . . The answer is not going to come from more federal controls on colleges or states, by telling families to judge the value of an education by the amount young graduates earn in the first few years after they graduate.

Warren, along with other academic leaders, warned about the unintended consequences of Obama’s proposals—reducing educational quality, cutting back essential student services, and disproportionately harming schools that serve larger numbers of at-risk students (Field 2012).

Sallie Mae and Ipsos (2012) report that, in 2012, families adjusted how they paid for college in three ways. First, parents cut their contributions from income and savings. For 2012, parents spent an average of $5,955 from their income and savings, down from $6,664 in 2011. Second, fewer families utilized scholarships—35% in 2012 compared with 45% in 2011. Some of this decline is attributed to colleges reducing the amount of scholarships that they are able to offer. Finally, students paid more out of pocket through their savings and income and borrowing more in 2012 than in previous years. In 2012, students contributed 18% of the total cost of college through borrowing compared with 15% the previous year and 14% in 2008–2010.

Are finances the only barrier to higher education? What other barriers can you identify?

Gender and Education

In the fall of 2013, 11.7 million women and 8.9 million men enrolled in undergraduate programs. In postbaccalaureate programs, there were 1.7 million females and 1.2 million males (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics 2014). Women represent a 57% majority in higher education (college or university) enrollment. In all measures—percentage of high school graduates completing college preparatory curriculum, percentage of high school graduates immediately enrolling in college, and total higher education enrollment—women rank higher than men. The American Council on Education (ACE; King 2006) attributes the increasing enrollment and degree attainment figures for women to the rising share of young women taking college preparatory courses during the 1990s and 2000s. Yet ACE concludes that there is “no consensus on the causes of the gender gap and little comprehensive empirical research upon which to base firm conclusions” (King 2006:20). That other industrialized countries are experiencing similar educational gains for women suggests that this phenomenon is not just an American one.

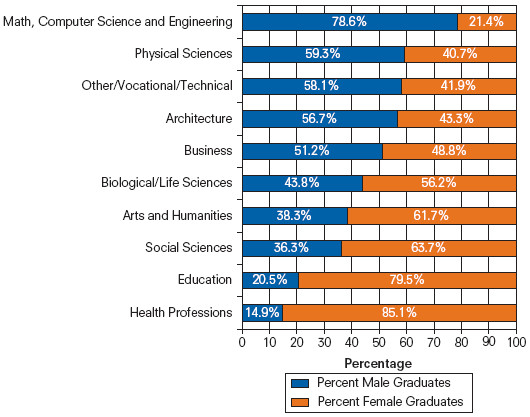

However, there is still some traditional gender segregation by major (refer to Figure 8.5). Men receive most bachelor’s degrees in Math, Computer Science, and Engineering (78.6%), while the percentage of women graduates is highest in the health professions (85.1%) and education (79.5%).

Figure 8.5 Bachelor’s degrees conferred by field of study and gender, 2009–2010

SOURCE: American Council on Education 2012.

The continued domination of men in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields remains a concern. Though gender differences in advanced-level math and science course enrollment have disappeared (Riegle-Crumb, Farkas, and Muller 2006) and girls are earning slightly higher grades in math and science classes than boys (U.S. Department of Education 2007), fewer women than men pursue these majors in college (Hill, Corbett, and St. Rose 2010).

A study by Linda K. Silverman (1986) suggests that females will eventually achieve less than males because they are gradually conditioned by “powerful environmental influences” such as the educational system, peers, and parents to believe that they are less capable than males. A “hidden curriculum” perpetuates gender inequalities in math and science courses. This curriculum takes the form of differential treatment in the classroom, where boys tend to dominate class discussion and monopolize their instructors’ time and attention, whereas girls are silenced and their insecurities reinforced (Linn and Kessel 1996). Research suggests that girls, especially gifted ones, fail to achieve their potential because of lower expectations of success, the attribution of any success to chance, and the belief that success will lead to negative social consequences (Silverman 1986).

Catherine Hill, Christianne Corbett, and Andresse St. Rose (2010) confirmed the effects of the social structure and the social environment on girls’ achievements and interests in science and math. The researchers identified how girls and women face persistent messages that STEM studies and successes are incompatible with traditional gender roles and expectations. Two negative stereotypes—girls are not as good as boys in math, and scientific work is better suited to boys and men—affect women’s and girls’ performance and aspirations in math and science. Hill and her colleagues recommend exposing girls to successful female role models to help counter these negative stereotypes.

Ethnicity/Race and Education

About 3.4 million students entered kindergarten in U.S. public schools last fall and already . . . researchers foresee widely different futures for them. Whether they are White, Black, Hispanic, Native American or Asian American will, to a large extent, predict their success in school. (Johnson and Viadero 2000:1)

In the mid-1990s, underrepresented minorities received less than 13% of all the bachelor’s degrees awarded (College Entrance Examination Board 1999). The College Entrance Examination Board noted that in the latter half of the 1990s, only small percentages of Black, Hispanic, and Native American high school seniors in the National Assessment of Educational Progress test samples had scores “typical” of students who are well prepared for college. Few students in these groups had scores indicating academic skills required for the most selective colleges or universities.

The 2012 graduation rate for first-time full-time undergraduate students who were first enrolled in fall 2006 was 59% (U.S. Deparment of Education, National Center for Education Statistics 2014). Graduation rates were highest for Asian (70.6%) students, followed by White (62.5%), Hispanic (51.9%), and Black (40.2%) students.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

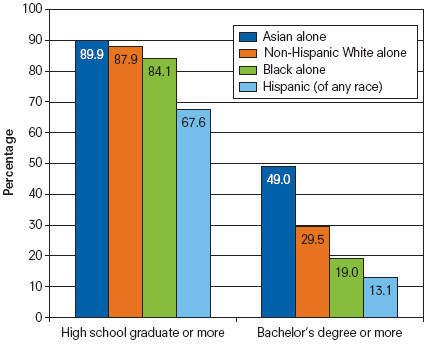

Figure 8.6 Differences in educational attainment (in percentages) by race and Hispanic origin for adults age 25 and older, 2013

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2014.

Persistent academic achievement gaps remain between Black, Hispanic, and Native American students and their White and Asian peers (refer to Figure 8.6 for differences in educational attainment). For example, among the 2013 college-bound students, White and Asian students had the highest average SAT critical reading score: 527 for Whites and 521 for Asians (College Board 2013). Lower critical reading scores were reported for Black students (431), Mexican or Mexican American students (449), and other Hispanic or Latino students (450). The same pattern exists for SAT mathematics and writing scores.

By 2015, there will be large increases in the number of Latino and Asian American youth, a substantial growth in the number of African American students, and a slight drop in the number of White students. The challenges to our educational system will only increase if demographic predictions hold true. Current educational gaps among racial and ethnic categories have the potential to grow into larger sources of inequality and social conflict.

Ethnicity/race, along with poverty, defines major sources of disadvantage in educational outcomes (Maruyama 2003). For example, among Latino families, poverty produces significant educational disadvantages: Parents may work multiple jobs, may not have the time to spend reading or going over homework with their children, and may not have the skills to read to their children. Economics also plays a role in dropout decisions. To support their families, Latino/a teens may leave school for a paying job. The power of parental and peer influence on Latino/a educational attainment has also been recognized. Parents may have expectations for their children that conflict with school expectations or requirements (American Association of University Women 2001).

According to Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson (1995), the pressure to conform to an image or a stereotype is so strong that it can actually impair intellectual performance. Steele and his colleagues tested the effects of a stereotype threat among African American (Steele 1997; Steele and Aronson 1995) and female college students (Spencer, Steele, and Quinn 1999). The stereotype threat is the risk of confirming in oneself a characteristic that is part of a negative stereotype about one’s group. The threat is situational, present only when a person can be judged, be treated in terms of the group, or self-fulfill negative stereotypes about the group (and the self) (Spencer et al. 1999). In their studies, Steele and his colleagues investigated the effect of the stereotype that African Americans and women have lower academic abilities than do White or male students.

It doesn’t matter if the individual actually believes the stereotype; if the stereotype demeans something of importance, such as one’s intellectual ability, the threat can be disrupting enough to impair intellectual performance (Steele and Aronson 1995). Subjects were compared in test-taking situations using Graduate Record Examinations (GRE), Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT), or American College Test (ACT) sample questions. In all study conditions where the tests were represented as affected by gender or race, African American and female students underperformed their comparison group. In situations where the stereotype threat was moderated (where subjects were not told that the tests produced gender differences or where subjects were not asked to report their race on the examination form), African American and female students performed as well as White or male students.

Violence and Harassment in Schools

School violence can be characterized on a continuum that includes aggressive behavior, harassment, property crimes, threats, and physical assault (Flannery 1997). Despite the public concern over school homicides, the percentage of youth homicides occurring at school is less than 2% of the total number of youth homicides. Victims of school violence may include students, teachers, and staff members. For the 2010–2011 school year, there were 1,336 homicides of youth ages 5 to 18 years. Eleven of those homicides occurred at school; the remaining 1,325 deaths occurred away from school. There were a total of 31 student, staff, and non-student school-associated violent deaths for the same year (Robers et al. 2014).

The deadliest U.S. incident took place in April 2007 at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, where 33 students and faculty were killed by a student. The deadliest international incident occurred in 1996 when a gunman killed 16 primary school students and one teacher, as well as himself, in Scotland. Though schools have been characterized as “battlegrounds” where both teachers and students fear for their safety (Kingery et al. 1993), they remain a safe place for students, the risk of a violent death being less than 1 in 2 million (Dinkes et al. 2009).

According to Hill and Kearl (2011) 48% of all students experience some sort of sexual harassment during their school lives.

© ZUMA Press, Inc / Alamy

The 2013 national school-based Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) survey conducted annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that nationwide about 7.1% of students had missed more than one day of school because they felt unsafe at school or on their way to or from school (CDC 2014). Among all students, 5.2% said they carried a weapon (a gun, knife, or club) on the school campus. About 6.9% of all students reported being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property, and about 8.1% of students had been in a physical fight on school property (CDC 2014).

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth are subject to verbal and physical harassment in high schools and middle schools. As reported by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network’s 2011 National School Climate Survey, 63.5% of LGBT youth reported feeling unsafe in school because of their sexual orientation (Kosciw et al. 2012). About 40% had experienced some form of physical harassment because of their sexual orientation; 18.3% had been physically assaulted for the same reason. Almost 82% of the surveyed students reported being verbally harassed in school the past year. The majority of students who had been harassed or assaulted did not report the incident to school staff or administrators. LGBT students’ experience with harassment negatively affected their school attendance, their academic performance, and, ultimately, their college aspirations. Students who experienced more frequent harassment, either verbal or physical, were more likely to indicate that they were not planning to go on to college than were students who did not experience the same type of harassment (Kosciw et al. 2012).

The extent of sexual harassment in schools has been documented by the Educational Foundation of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) (Hill and Kearl 2011). According to its 2010–2011 report, 48% of students experience some form of sexual harassment during their school lives. Girls are more likely than boys to experience sexual harassment. How is sexual harassment defined in schools? The definition offered by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2001) under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 reads,

Unwanted sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitutes sexual harassment when submission or rejection of this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.

In schools, sexual harassment can include such behaviors as sexual messages written on walls or in locker rooms, sexual rumors, being flashed or mooned, being brushed up against in a sexual way, or being shown sexual pictures or material of sexual content (Fineran 2002) and includes online harassment (e.g., receiving unwelcome comments or photos through texts, being the subject of sexual rumors or information) (Hill and Kearl 2011). Sexual harassment of students has serious consequences, including mental health symptoms (such as loss of appetite, disturbances in sleep, feelings of isolation, and sadness) and school performance difficulties (Fineran 2002).

Preventing Violence

Sexual Assault on Campus

Community, Policy, and Social Action

As a nation, we support the principle of educational excellence and, along with it, the assumption of educational opportunity for all, but in reality, we have an educational system that embraces these ideas yet fails to achieve them (Ravitch 1997). The educational experiences of poor and minority students fundamentally conflict with the principles of public education, namely, that public schools should provide these children with opportunities so that all children can succeed as a result of hard work and talent (Maruyama 2003). Reformers argue that school choice, standardized testing, and school vouchers are improving our educational system. Critics argue that these strategies threaten to erode an already-weak public school structure. There is a deepening chasm between what the American public deems important in education (safety, skills, discipline) and the goals of the reform movement (access, standardization, multiculturalism) (Finn 1997). Although we have not completely abandoned our public educational system, we still have not found a way to agree on what is appropriate or essential to save it.

Policy Responses—The Basis for Educational Reform

The Educate America Act of 1994 and NCLB

Providing fuel to the reform movement have been congressional acts passed in 1994 and 2001. Although they were adopted under presidents from different political parties, both congressional acts provide strong support for school reform and, along with it, changes to our educational system.

The Goals 2000: Educate America Act introduced the notion of “standards-based reform” at the state and community levels. This 1994 act, signed into law by President Clinton, provided the grounds for sweeping reform at all levels and from all angles: curriculum and instruction, professional development, assessment and accountability, school and leadership organization, and parental and community involvement. However, school reform hinged on the use of student performance standards and the creation of the National Education Standards and Improvement Council. A summary of the act reported, “Performance standards clearly define what student work should look like [at] different stages of academic progress and for diverse learners” (“Goals 2000” 1998:14). The act established performance and content standards in math, English, science, and social studies, and it encouraged participation from the entire community—local officials, educators, parents, and community leaders—in raising academic standards and achievement.

When George W. Bush signed the NCLB Act, he approved a plan that increased federal pressure on states to pursue a standards-based reform agenda. Under NCLB, states are required to institute a system of standardized testing for all public school students in Grades 3 to 8 and high school, about 45 million tests annually. Each state must have a plan for adequate yearly progress (AYP) toward the goal of academic proficiency for all students, a 100% rate regardless of economic status, ethnicity/race, gender, or disability, by 2014.

The more controversial elements of the act signed by George W. Bush included the provision for public school choice and charter schools. The act provided support to permit children in chronically failing public schools to transfer to other schools with better academic records. The bill also provided for annual testing of students in reading and math in the third to eighth grades, which would establish academic records for comparison. If there were no improvements in test results in two years, parents would have the option to move their children to another school. In such an event, the school district would be required to pay for the child’s transportation to a better school, and the failing school would lose the per-pupil payment. Critics argued that such school choice provisions would work only if there were schools to choose from within a district and if there was room in these schools. The law does not provide school leaders with the means to create new slots for students (Schemo 2002).

Although expressing commitment to the basic intent of NCLB, many state leaders and educators expressed frustration in implementing the act’s requirements and achieving its goals. In particular, school administrators and educators were critical of a key feature of NCLB: the one-size-fits-all accountability standard that assumes that all schools, districts, and groups of students will demonstrate progress according to the standardized measures. The standards, said critics, seriously compromise the abilities of schools to address the unique educational needs of special education students, low-income and minority students, and students with limited English proficiency.

In their 2010 proposal to reauthorize NCLB, the Obama administration set a new educational goal: “Every student should graduate from high school ready for college or a career regardless of their income, race, ethnic or language background, or disability status” by 2020 (U.S. Department of Education 2010:3). The proposal identified four policy and programming areas: improving teaching and principal effectiveness, providing information to families to evaluate and improve their children’s schools and to educators to help improve student learning, implementing college- and career-ready standards and assessments, and improving student learning and achievement in the lowest-performing schools by providing support and effective interventions. In 2012, the Obama administration granted NCLB waivers to 24 states, in exchange for adopting the administration’s educational standards and a new focus on accountability and teacher effectiveness. These states will need to set new performance targets for students and schools but will not be sanctioned as they were under the old law for schools failing or for not making adequate progress. More states will seek a waiver under the new plan (Hu 2012). Many characterized this as the beginning of the end of the NCLB era.

Since 2010, 43 states have voluntarily adopted a set of college and career-ready standards for English language arts/literacy and math for all kindergarten through 12th-grade students. The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) propose clear and consistent standards for what a child should know and be able to do at each grade level, allowing school districts to design their own curricula and teachers to implement their own teaching methods. CCSS encourages students to demonstrate and learn critical thinking skills, moving away from memorization to a deeper understanding of material. However, critics argue that the standards do not consider the diversity of the U.S. student population and fail to consider the differences in student learning. As of December 2014, several states that adopted CCSS have opted out. National polls suggest that parents, teachers, and students have grown tired and suspicious of high-stakes standardized testing (Kirp 2014).

Promoting Educational Opportunities—Head Start and Prekindergarten

Called the most popular and most romantic of the War on Poverty efforts (Traub 2000), Head Start remains the largest early childhood program. More than 30 million poor and at-risk preschoolers have been served under Head Start since 1965. Head Start began with a simple model of service: organized preschool centers. At these centers, programs focused on the “whole child,” examining and encouraging physical and mental health. Integrating strong parental involvement, Head Start provided a unique program targeting child development and school preparedness. Over the years, the Head Start program expanded to serve school-age children, high school students, pregnant women, and Head Start parents. In 1994, amendments to the Head Start Act established Early Head Start (EHS) services targeting economically disadvantaged families with children 3 years old or younger. EHS serves both children and their families through a comprehensive service plan that promotes child development and family self-sufficiency (Wall et al. 2000).

The effectiveness of Head Start programming, particularly the educational component, has been the focus of public and government debate (Washington and Oyemade Bailey 1995). Early program research and evaluation efforts were spotty, with the major findings pointing to short-term or “fade out” gains in student learning and testing (Washington and Oyemade Bailey 1995). In its 2005 impact study report, HHS compared the performance of Head Start children with non–Head Start children from fall 2002 through summer 2005. For Head Start children in both age groups, small to moderate positive effects were found in prereading, prewriting, and vocabulary skills. Both groups also had significantly better access to health care; in addition, the 3-year-olds reported significantly better overall health than did the non–Head Start group. Positive parenting practices (e.g., reading to one’s child) were also documented for children in both Head Start age groups (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2005). Head Start was reauthorized in 2007 with increased funding for Migrant and Seasonal Head Start and the Indian Head Start programs. The reauthorization also increased educational requirements for Head Start teachers.

As of 2013, there were 53 state-funded preschool programs in 40 states and in the District of Columbia (Barnett et al. 2013). These programs are funded, controlled, and administered by the state, serving children ages 3 and 4. About 1.3 million children attended state-funded pre-K in 2013. Pre-K programs have gained popularity as an alternative to Head Start, promising a preschool experience for all children, regardless of economic need. Research indicates that effective, high-quality pre-K programming can improve the academic and social-emotional outcomes for students, with some effects lasting into middle and high school.

The first universal prekindergarten (or pre-K) program was established in Georgia in 1996. The program is open to all 4-year-olds regardless of household income. In their comparison between Head Start and Georgia pre-K students, Gary Henry, Craig Gordon, and Dana Rickman (2006) concluded that economically disadvantaged pre-K students were better prepared for kindergarten than children who attended Head Start. Pre-K students performed significantly higher in picture-word vocabulary, recognition of letters and words, and oral and written skills at the beginning of kindergarten than their Head Start peers.

Mentoring, Supporting, and Valuing Networks

Women and Girls

In its 1992 report, the AAUW called on local communities and schools to promote programs that encourage and support girls studying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Studies indicate that most girls and women learn best in cooperative, rather than competitive, learning activities. With seed money from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, the AAUW Educational Foundation initiated the Girls Can! Community Coalitions Project in 1996. The project funded 10 community-based projects that encouraged schools and community groups to improve girls’ educational opportunities.

AAUW continues its support of STEM projects through the National Girls Collaborative Project established in 2005. The National Girls Collaborative Project goals include maximizing access to shared resources within projects and with public and private organizations interested in expanding girls’ STEM participation, strengthening the capacity of existing and evolving projects by sharing promising research and program models, and using the collaboration of individual girl-serving STEM programs to create the tipping point for gender equity in STEM (National Girls Collaborative Project 2014).

Fourteen regional collaborative sites operate in California, Florida, Massachusetts, the mid-Atlantic, and the Northwest. Small mini-grants help fund tutoring, career days, field trips, and special events to expose girls and boys to STEM education and careers. One such grant helped fund California State Summer School for Mathematics and Science (COSMOS), a month-long residential academic experience for top California high school students in science and mathematics. Students reside at one of four University of California campuses—Davis, Irvine, San Diego, or Santa Cruz—while taking COSMOS classes in their areas of interest.

Mentoring can also begin in one’s own community and among friends. In 1996, Michele Deane noticed that a number of girls in her Boyle Heights (Los Angeles, California) neighborhood did not have anything to do after school. She created a youth organization for local Mexican American and Latin American girls and women, beginning with a group of her friends, that now serves more than 200 girls and women each year. According to Deane, her organization, Girls Today, Women Tomorrow, created a state of consciousness for thinking “bigger”:

What do I want to do? Who can I become with the support of everyone around me? It’s a state of consciousness coming from the world around you instead of seeing only the obstacles. Once they saw other people doing it, they started doing it for their friends, for the younger kids growing up. (Quoted in Wiland and Bell 2006:187)

The volunteer program includes fitness activities, a computer lab, video shooting and editing classes, and a community garden. The garden serves as a connection to the environment and the girls’ Latin culture and raises their awareness about the kind and quality of food they consume. Program graduates return to the program and serve as mentors and volunteers. Ginette Sanchez credits the program for her academic and life successes: “I always thought that I wouldn’t have a future. Now that I have positive role models, I’m going to college and I’m being positive by thinking that I’m going to be someone in life as well” (quoted in Wiland and Bell 2006:189).

Teach for America

Voices in the Community

Wendy Kopp

Wendy Kopp’s vision for Teach for America began as her senior undergraduate thesis. This Princeton graduate is the youngest and only female to receive the university’s Woodrow Wilson Award, the highest honor bestowed to alumni. In the following excerpt from her book One Day, All Children: The Unlikely Triumph of Teach for America and What I Learned Along the Way, Kopp (2001) explains how Teach for America began with an idea:

Princeton University was not the most likely place to become concerned about what’s wrong in education, but it made me aware of students’ unequal access to the kind of educational excellence I had previously taken for granted. I got to know students who had attended public schools in urban areas—thoughtful, smart people—as well as students who attended the East Coast prep schools. I saw the first group struggle to meet the academic demands of Princeton and the second group refer to it as a “cake walk.” Clearly at Princeton I could not glimpse the depths of educational inequity in our country, but the disparities I did see got me thinking. It’s really not fair, I thought, that where you’re born in our country plays a role in determining your educational prospects.

Wendy Kopp was the first to receive the John F. Kennedy New Frontier Award, an honor presented to Americans under the age of 40 for their commitment to public service.

BRIAN SNYDER/REUTERS/Newscom

In an effort to figure out what could be done about this problem, I organized a conference about the issue. At this time I led an organization called the Foundation for Student Communication. . . . So in November of my senior year, my colleagues and I gathered together fifty students and business leaders from across the country to propose action plans for improving our educational system. . . .

At one point during a discussion group, after hearing yet another student express interest in teaching, I had a sudden idea: Why didn’t this country have a national teacher corps of top recent college graduates who would commit to teach in urban and rural public schools? A teacher corps would provide another option to the two-year corporate training programs and grad schools. It would speak to all college seniors who were searching for something meaningful to do with our lives. . . .

The more I thought about it, the more convinced I became that this simple idea was potentially very powerful. If top recent college graduates devoted two years to teaching in public schools, they could have a real impact on the lives of disadvantaged kids. Because of their energy and commitment, they would be relentless in their efforts to ensure their students achieved. They would throw themselves into their jobs, working investment-banking hours in classrooms instead of skyscrapers on Wall Street. They would question the way things are and fight to do what was right for children.

Beyond influencing children’s lives directly, a national teacher corps could produce a change in the very consciousness of our country. . . .

In the end, I produced “A Plan and Argument for the Creation of a National Teacher Corps,” which looked at the educational needs in urban and rural areas, the growing idealism and spirit of service among college students, and the interest of the philanthropic sector in improving education. The thesis presented an ambitious plan: In our first year, the corps would inspire thoughts of graduating college students to apply. We would then select, train, and place five hundred of them as teachers in five or six urban and rural areas across the country. (pp. 5–6, 10)

In its first year, Teach for America received 2,500 applications, of which, as Kopp planned, 500 were selected and trained for two years of teaching. Since then, more than 37,000 teachers have been placed or are currently placed in more than 50 urban and rural sites throughout the United States. Corps members’ salaries and health benefits are paid directly by the school districts they are placed in.

Kopp adapted the Teach for America model to a global model, cofounding Teach for All in 2007.

What social problem does Teach for America address? What evidence is necessary to determine if it is an effective strategy?

SOURCE: Kopp 2001:5–6, 10. Published by PublicAffairs, a member of Perseus Books Group.

LGBT Students

The best estimate of the number of LGBT students is about 5% to 6% of the total student population (Human Rights Watch 2001). LGBT youth have been a driving force behind creating change in their schools and communities. Support groups and organized student activities have emerged in states such as California, Illinois, and Washington, providing valuable support to LGBT teens and their friends and families (Bohan and Russell 1999; Human Rights Watch 2001).

One such student group is the Gay–Straight Alliance (GSA) in East High School in Salt Lake City, Utah. As Janis Bohan and Glenda M. Russell (1999) chronicle, a group of students proposed creating a student alliance to provide a support network for LGBT students and their heterosexual friends in October 1995. In response to the students’ proposal, the school board and the state legislature banned all noncurricular clubs rather than allow the GSA. The club continued to meet, paying rental and insurance fees for the use of school facilities. According to Bohan and Russell, students indicated how the club had a positive impact on their lives. The alliance served as a safe refuge, decreasing their feelings of isolation and vulnerability, students said, and they reported decreases in substance abuse, depression, suicidal impulses, truancy, and conflict with parents. The straight student members also reported positive effects. In September 2000, Utah’s Salt Lake City School District Board of Education voted to permit noncurricular student groups to meet on school grounds, reversing its 1995 decision against the GSA (Human Rights Watch 2001). According to the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, there are more than 4,000 registered clubs for LGBT students and their friends throughout the United States.

Schools are allowing students to participate in the national Day of Silence in April. A vow of silence for the day symbolizes the silencing effect of antigay harassment and bullying. The event was founded in 1996 by students at the University of Virginia. In 2012, the day was observed in 9,000 schools in over 70 countries. Although some religious and parent groups object to what they consider “promotion” of homosexuality, most agree that it is important to create and promote a safe school environment for LGBT youth.

Antiviolence and Antibullying Programs in Schools

As awareness of school violence has increased, so have the calls for effective means of prevention (Aber, Brown, and Henrich 1999). The current focus is less on reacting to school violence and more on promoting school safety through prevention, planning, and preparation (Shaw 2001).

The largest and longest-running school program focusing on conflict resolution and intergroup relations is the Resolving Conflict Creatively Program (RCCP). Initiated in 1985 in New York City by the local chapter of Educators for Social Responsibility, the program is a research-based K–12 school program in social and emotional learning. RCCP is in 400 schools nationwide, serving 6,000 teachers and more than 175,000 students. RCCP begins with the assumption that aggression and violent behavior are learned and therefore can be reduced through education. The program teaches children conflict resolution skills, promotes intercultural understanding, and provides models and opportunities for positive ways of dealing with conflict and differences. For kindergarten students, puppets and other objects are used to illustrate how conflict can be resolved by talking rather than hitting. RCCP includes training for teachers, parents, administrators, and school staff.

An evaluation of the New York City programs indicated that students who received RCCP instruction developed more positively than did students without any RCCP exposure. RCCP students were more prosocial, perceived their world in a less hostile way, saw violence as unacceptable, and chose nonviolent ways to resolve conflict. Reading and math scores were higher for RCCP students, especially those who had 25 RCCP lessons over the school year. Evaluators concluded that the RCCP-intensive children were more able to focus on academics when there was less conflict with peers (Shaw 2001).

The Safe Schools Improvement Act and the Student Non-Discrimination Act were introduced in Congress in 2011 in an effort to support safe schools and enrich the learning environment. Both bills would require schools that accept federal funding to track, create policy regarding, and demonstrate reduction in bullying and harassment incidents. Bullying and harassment data would be reported biennially. While ensuring the safety and well-being of all students, the bills were applauded for their focus on students with disabilities and LGBT students.

With the increase in school violence, more attention has been given to school safety through security screening or police–school liaison projects. Schools are more aware of the links between safety and violence and other student behaviors such as dropout rates, academic failures, bullying, and suicide (Shaw 2001). Violence prevention programs have become common throughout the country with the primary focus on early education. In addition to the RCCP, national initiatives include the Office of Safe and Healthy Students and the Safe Schools/Healthy Students Initiative. Regional initiatives include the PeaceBuilders elementary program and Students Against Violence Everywhere. U.S. and international approaches focus more on school safety and less on school violence, use programs to serve students and the entire school population, develop school–community partnerships, and use evaluated program models (Shaw 2001). The most effective school-based violence prevention programs are those that include parental involvement and support, with parents backing school limits and consequences at home (Flannery 1997). Antiviolence programs have also been established on college and university campuses. As noted in Chapter 4, “Gender,” schools receiving federal funding under Title IX are required to respond promptly and effectively to sexual violence against students.

Does Having a Choice Improve Education?

There is a new term now, public school choice. Data issued by the National Center for Education Statistics reveal that more parents are turning away from local public schools to private schools or charter schools (Zernike 2010). As of the 2011–2012 school year, 42 states and the District of Columbia have passed charter school legislation. There were 5,696 charter schools in operation from 2011 to 2012, with 2.1 million students enrolled (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics 2014). In the 2011–2012 school year, California enrolled the largest number of students in charter schools (413,000 students), followed by the District of Columbia (29,000 students).

Parents and children have two additional options within the public education system: magnet schools and charter schools. Magnet schools offer specialized educational programs from elementary school through high school. These schools are organized around a theme such as performing arts, science, technology, or business or around different instructional designs such as free (where students can direct their own education) or open schools (with informal classroom designs). Often, magnet schools are placed in racially isolated schools or neighborhoods to encourage students of other races to enroll. Magnet schools have been criticized for creating a two-tier system of education (Kahlenberg 2002).

Charter schools are nonsectarian public schools of choice that operate free from most state laws and local school board policies that apply to traditional public schools. Charter schools are funded with public funds, like public schools. A charter contract establishes the school’s operation, usually limited to three to five years, detailing the school’s mission and instructional goals, student population, educational outcomes, and assessment methods, along with a management and financial plan. These schools have grown in popularity since 1991, when Minnesota became the first state to pass an outcome-based school law. Charter schools are characterized by innovative teaching practices and accountability to students and families. If a school fails to meet its goals, it cannot be renewed under its charter.

School choice has become an even hotter topic with the idea of school vouchers. Simply stated, school vouchers allow the transfer of public school funds to support a student’s transfer to a private school, which may include religious institutions. Supporters of school vouchers argue that the system would give parents more choice and freedom in school selection and would create incentives for school improvement (Good and Braden 2000; Kennedy 2001).