Chapter 7 Families

Learning Objectives

- 7.1 Describe how the sociological perspectives explain social problems related to the family

- 7.2 Summarize the effects of divorce on children

- 7.3 Identify why the U.S. teen pregnancy rate is the highest in the developed world

- 7.4 Explain the difference between physical abuse and neglect

- 7.5 Explain the relationship between cohabitation and marriage

Do you recall the first “crew” you ever hung out with? You know the one—all its members know each other, speak the same language, laugh at the same jokes, dress alike, and maybe even look alike. Sound familiar? These are the people with whom you slept, ate, and lived in your own home: your family.

You may not always think of it this way, but your family is part of the larger social institution of “the family.” Consider for a moment that your family was among the 115 million family groups counted by the U.S. Census in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau 2013). What does your family have in common with the other family groups? Your first response might be that your family has nothing in common with the others. No other family has the unique arrangement or history of individuals related through blood or by choice. From this position, any problem experienced by your family, such as a divorce, would be defined as a personal trouble. A divorce is a private family matter kept among immediate family members. It would be none of anyone else’s business.

If we use our sociological imagination, however, we can uncover the links between our personal family experiences and our social world. Divorce is not just a family matter but also a public issue. Looking at the recent divorce rate of 3.6 divorces per 1,000 people, divorce occurs not in just one household but in millions of U.S. households. It affects the economic and social well-being of millions of women, men, and children. Divorce challenges the fundamental values of home and love and the value of the family itself. Divorce could be everyone’s business.

In this chapter, our goal is to explore this private, yet public, world of the family. For our discussion, we define the family as a construct of meaning and relationships both emotional and economic. The family is a social unit based on kinship relations—relations based on blood, and those created by choice, marriage, partnership, or adoption. A household is defined as an economic and residential unit. These definitions allow for the diversity of families that we discuss in this chapter, while not presenting one configuration as the standard. As you’ll see, the family as we think we know it may not exist at all.

Myths of the Family

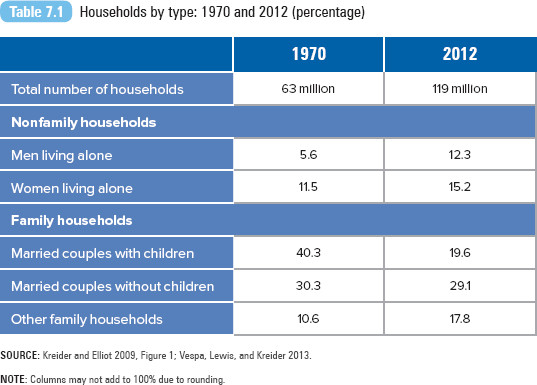

The nuclear family—two parents and their biological children living together—is exalted as the ideal family. Yet families are much more diverse than this. First, the percentage of families composed of married couples with children declined from 40.3% in 1970 to 19.6% in 2010 (Vespa, Lewis, and Kreider 2013). Take note—the traditional family form, married with children, is less than a quarter of all U.S. households. The largest family form is married couples without children (29.1%).

Public attitudes are shifting away from traditional ideals of marriage and childbearing in Western industrialized societies such as the United States, Austria, (West) Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, and the Netherlands. Zoya Gubernskaya (2010) found that female, never-married, better-educated, employed, and secularized individuals had less traditional views about marriage and children. Support for the statement that “people who want children ought to get married” declined in these countries from 1988 to 2002. Gubernskaya attributes the increasing nontraditionalism to a rise in secularization, a shift toward individualism, and an increasing focus on education and employment achievement that are at odds with traditional family formation.

Second, the only increase in family groups during this period came in the category of “other family households.” Other family households include families with other relatives residing, what we also refer to as extended families. When President Obama moved into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, much attention was paid to the fact that his mother-in-law, Marian Robinson, would also be a resident. The last time a mother-in-law had been a full-time White House resident was during Harry Truman’s presidency. Other family households made up 17.8% of all U.S. households, increasing from 10.6% in 1970. Included in this category are 8.2 million single-parent families, 6 million headed by mothers and 2.2 million headed by fathers. Finally, there has been an increase in the percentage of nonfamily households (refer to Table 7.1).

SOURCE: Kreider and Elliot 2009, Figure 1; Vespa, Lewis, and Kreider 2013.

NOTE: Columns may not add to 100% due to rounding.

In 2007, U.S. Census data revealed that for the first time, more American women were living without a husband than with one. Based on 2005 data, 51% of women were living without a spouse, an increase from 35% in 1950 and 49% in 2000. In contrast, 47% of men reported living without a spouse in 2005. The pattern varies by race, with 30% of Black women, 49% of Hispanic women, 55% of non-Hispanic White women, and 60% of Asian women reporting that they were living with a spouse. Analysts reported that several factors contributed to the increase in the number of single women: late marriage for women, women living longer as widows or after a divorce, and women being more likely than men to delay remarriage (Roberts 2007).

In addition to the false image of the nuclear family, we also embrace other myths about the family. We tend to believe that the families of the past were better and happier than modern families are. We believe that families should be safe havens, protecting their members from harm and danger. And a final myth relates to the topic of this book: we also assume that the family and its failings lead to many of our social problems.

There is a persistent belief that nontraditional families, such as divorced, fatherless, or working-mother families, threaten and erode the integrity of the family as an institution. These “pathological” family forms are blamed for drug abuse, delinquency, illiteracy, and crime. As a group, female-headed households were condemned in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, also known as the Welfare Reform Act, for their dependency on the public welfare system.

Who’s at Home?

Sociological Perspectives on the Family

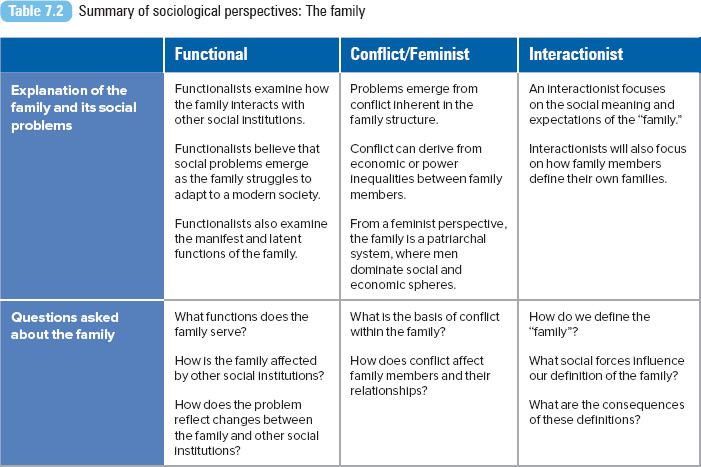

Functionalist Perspective

From a functionalist perspective, the family serves many important functions in society. Some functionalists claim that the family is the most vital social institution. The family serves as a child’s primary group, the first group membership we claim. We inherit not only the color of our hair or eyes but also our family’s social position. The family confers social status and class. The family helps define who we are and how we find our place in society. And, without the family, who would provide for the essential needs of the child: affection, socialization, economic support, and protection?

Social problems emerge as the family struggles to adapt to a modern society. Functionalists have noted how many of the family’s original functions have been taken over by organized religion, education, work, and the government in modern society (Lenski and Lenski 1987), but still, the family is expected to provide its remaining functions of raising children and providing affection and companionship for its members (Popenoe 1993). From a functionalist perspective, the family is inextricably linked to the rest of society. The family does not work alone; rather, it functions in concert with the other institutions. Changes in other institutions, such as the economy, politics, or law, contribute to changes and problems in the family.

Consider the education of children. Before the establishment of mandatory public school systems, the family educated its own children. As a formal system, education has become its own institution, taking primary responsibility for educating and socializing everyone’s children. Functionalists examine how the institutions of the family and education effectively work together. To what extent should parents participate in their children’s education, and to what extent is the educational system responsible for raising our children?

Because of this perspective’s emphasis on the family and its social and emotional functions, when the family fails—as in the case of divorce or domestic violence—functionalists take these problems seriously. These problems afflict the family and, according to functionalists, can lead to additional problems in society, such as crime, poverty, or delinquency.

Conflict and Feminist Perspectives

For the conflict theorist, the family is a system of inequality where conflict is normal. Conflict can derive from economic or power inequalities between spouses or family members. From a feminist perspective, inequality emerges from the patriarchal family system, where men control decision-making in the family. Persistent social ideals that view the woman as homemaker and the man as breadwinner are problematic from both perspectives. Men’s social and economic status increases as their work outside the home is more visible and rewarded, whereas women’s work inside the home remains invisible and uncompensated.

The family structure, as our society has come to define it, upholds a system of male social and economic domination. Theorist Friedrich Engels argued that the family was the chief source of female enslavement. Within the family, Engels believed, the husband represented the bourgeois, whereas his wife represented the proletariat (Engels 1902). Among the middle class, where property is the primary consideration, marriage was a respectable form of prostitution. Just as members of the proletariat were oppressed in the economy, women were oppressed at home. Freedom for women, wrote Engels, would come with their economic independence and participation in the workplace (activities based outside the home).

Feminist theory also examines power within the family. According to this perspective, men can maintain their position of power in the family through violence or the threat of violence against women. Feminists argue that domestic violence cannot be solely explained by men’s individual attitudes and behavior. Rather, violence against women is linked to larger social structures of male dominance, such as political, economic, and other social institutions like the family. Theorists have encouraged the integration of feminist analyses of gender and power to better comprehend the mechanisms leading to violence, arguing that to stop such violence, structures of gender inequality must change (Brownmiller 1975).

Feminist theorists have also acknowledged how the cultural differences of domestic violence have not been fully recognized. According to Tricia Bent-Goodley (2005), “research has largely focused on White and poor women, despite the fact that domestic violence crosses race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion and sexual orientation” (p. 197). She notes that this narrow research focus has encouraged the perception that women of color, middle- and upper-class women, and women in same-sex relationships do not experience domestic violence, despite evidence to the contrary. And though data indicate that disabled women experience a greater risk of abuse and violence in comparison with the general population, studies on the nature of the oppression and consequences of domestic abuse against women with disabilities still remain largely ignored (Mays 2006).

Families are also subject to powerful economic and political interest groups that control family social programs and policies. Conflict arises when the needs of particular family forms are promoted while others are ignored. As discussed in Chapter 1, the Defense of Marriage Act systematically devalued nonheterosexual unions or couples. To resolve social problems in the family, both perspectives suggest the need for structural change.

Interactionist Perspective

Through social interaction, we create and maintain our definition of a family. As we do this, it affects our larger social definition of what everyone’s family should be like and how we envision the family that we create for ourselves.

Within our own families, our interaction through words, symbols, and meanings defines our expectation of what the family should be like. How many children are in the family? Who does the housecleaning? Who gets to carve the holiday turkey? What does it mean to be a wife, a husband, a partner? As a family, we collectively create and maintain a family definition on which members agree. Problems arise when there is conflict about how the family is defined. A couple starting their own family must negotiate their own way of doing things. Two partners may carry definitions and expectations from their families of origin, but together, they create a new family reality.

Problems may also occur when partners’ expectations of family or marriage do not match their real lives. In our culture, romantic love is idealized, misleading individuals to believe that they are destined for a fulfilling emotional partnership with one perfect mate. After the realities of life set in, including the first fight, the notion of romantic love is shattered. Couples recognize that it may take more than romantic love to make a relationship work.

Conflict also arises when a family arrangement is different from societal norms and expectations. Blended families, gay or lesbian families, or single-parent families become social problems based only on how they deviate from the definition of a “normal” family. Society assigns meaning to particular family groups or relations. More than half a century ago, when a child was born to unmarried parents, it was assumed that the child was unwanted and that the child’s future would be less than promising. There was a major social stigma with being referred to as a bastard child. But because currently one in three births involves parents who are not legally married, and most births are wanted or planned, the use of the term bastard has disappeared, as has the stigma attached to such a birth (Rutter and Tienda 2005).

But definitions vary by culture. In South Korea, there is still a strong negative stigma regarding unwed motherhood. In 2007, 2% of all births in South Korea were to unmarried women, compared with 40% of all U.S. births. The Korean discussion on unmarried motherhood has focused on how to eradicate the “evil” of unmarried motherhood as it threatens the patriarchal social structure (Kim and Davis 2003). Journalist Choe Sang-Hun (2009) reports how “social pressure drives thousands of unmarried women to choose between abortion, which is illegal but rampant, and adoption, which is considered socially shameful but is encouraged by the government” (p. A6). Unmarried women who decide to raise a child risk a life of poverty and disgrace, even being ostracized by family members. Lee Mee-Kyong, whose family disowned her after the birth of her son, says, “Once you become an unwed mom, you’re branded as immoral and a failure. You fall to the bottom rung of society” (quoted in Sang-Hun 2009:A6).

Putting all our separate definitions of the family together, we create a portrait of what the family should be like. But as some political and religious forces uphold and encourage a heteronormative conception of the nuclear family as the norm, by default, other family forms are considered deviant against some set of moral codes, or not families at all (Smith 1993). Heteronormativity refers to the promotion of heterosexual, married, monogamous, White, and upper-middle-class norms (Branzel 2005).

However, in 2010, sociologists Brian Powell, Catherine Bolzendahl, Claudia Geist, and Lara Carr Steelman reported how our definition of the family was expanding. In the 2003 Constructing the Family Survey, respondents were asked about which living arrangements constituted a family. Each survey respondent indicated that an arrangement with a husband, a wife, and children constituted a family. However, the majority also defined the following as a family: single mothers (94%) or single fathers (94.2%) with children and married couples with no children (93.1%). According to the researchers, “the most-agreed-upon family forms tend to rely on at least one of two prerequisites: the presence in the home of a child, and a legal heterosexual relationship—or, more precisely, a relationship that is not a same-sex relationship or a cohabitating heterosexual one” (Powell et al. 2010:20). There was less agreement that an unmarried cohabitating couple with children could be defined as a family (78.7%). For arrangements with same-sex couples, couples with children were more likely to be defined as a family than couples without children (e.g., 55% of the sample defined two women with children as a family compared with 26.8% who defined two women with no children as a family) (Powell et al. 2010).

Refer to Table 7.2 for a summary of all sociological perspectives on the family.

Problems in the Family

Divorce

If you do an Internet search on divorce, you might be surprised at your search results. In addition to divorce facts and access to support groups, you’ll find handy guides to complete your own divorce paperwork. Looking to save time, money, and pain? Please try our services. Looking for a divorce lawyer? Why not search for one online? And if you’d like to send a divorce greeting card that says, “Happy to be without you,” you can find one of those online, too.

Divorce was a rare occurrence until the 1970s. In the 1950s and 1960s, the divorce rate was about 2.2 to 2.6 per 1,000 individuals (U.S. Census Bureau 1999). With the introduction of no-fault divorce laws in the 1970s, the divorce rate began to climb, reaching a high of 5.3 in 1979 and 1981 (U.S. Census Bureau 1999). The increase in divorce rates has been attributed to other factors: the increasing economic independence of women, the transition from extended to nuclear family forms, and the increasing geographic and occupational mobility of families. Furthermore, as our societal and cultural norms about divorce have changed, the stigma attached to divorce has decreased.

In recent years, the divorce rate has remained stable around 3.5 divorces per 1,000 individuals in the total U.S. population. The rate was 4.0 in 2000, declining to 3.6 in 2011 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013). The U.S. marital rate declined during the same period: from 8.2 for 2000 to 6.8 for 2011 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013). When compared with European Union (EU) countries, the United States has the higher divorce rate. In 2008, the estimated divorce rate for the EU was 2.0 per 1,000 (Eurostat 2009). EU marital rates were also lower for 2008, at 4.87 per 1,000 (Eurostat 2009).

Recent Census data on divorce indicate that certain groups are more susceptible to divorce than others. Based on 2001 Census data, Rose Kreider (2005) reported that although one in five U.S. adults had been divorced, the percentage of those having been divorced was highest among men and women 50 to 59 years of age (41% and 39%, respectively). The majority of separated and divorced men and women were between 25 and 44 years of age. The median age of divorce from first marriage was 29.4 years for women and 31.4 years for men. Divorce rates are higher among couples married before 20 years of age, living at 200% of the poverty level, with a high school degree or some college, or working full-time (Kreider and Fields 2002).

Sociologists have paid particular attention to immediate and long-term effects of divorce on children. In general, the research indicates that children with divorced parents have moderately poorer life and educational outcomes (emotional well-being, academic achievement, labor force participation, divorce, and teenage childbearing) than do children living with both parents (Amato 2000; Hetherington and Kelly 2002). For example, boys living with a divorced mother are four times more likely to display severe delinquency or to engage in early sexual intercourse than are those living in two-parent households (Simons 1996). Some of these effects carry into adolescence and young adulthood (Amato and Keith 1991; Cherlin, Kiernan, and Chase-Lansdale 1995), with more negative outcomes for adult females than for adult males, such as a greater incidence of relationship conflict or difficulty with intimate relationships. Children of divorce have less commitment to the idea of lifelong marriage than children from intact families (Amato and DeBoer 2001) and have a higher likelihood of instability in their own marriages (Wolfinger 2005).

Conversely, research also suggests that marital separation is beneficial to the well-being of children (Videon 2002). Favorable outcomes have included increased maturity, enhanced self-esteem, and increased empathy among children from divorced families (Brooks Conway, Christensen, and Herlihy 2003). Parental divorce may shift children from traditional sex-role beliefs and behavior toward more androgynous attitudes and behavior (MacKinnon, Stoneman, and Brody 1984). Parent–child relations are important influences on children’s well-being, even mediating the effects of marital dissolution (Videon 2002). Divorce is less disruptive if both parents maintain a positive relationship with the child, if parental conflict decreases after separation or divorce, and if the level of socioeconomic resources for the child is not reduced (Amato and Keith 1991).

Research consistently indicates that although men experience minimal economic declines after divorce, most women experience a substantial decline in household income and increased dependence on social welfare (Smock 1994). Data from the 2001 U.S. Census show that although only 15% of recently divorced men lived in households where they (or someone they lived with) received noncash public assistance, more than twice as many recently divorced women (or someone they lived with) received noncash public assistance (34%) (Kreider 2005). As first reported in Chapter 2, the poverty rate among female-headed households (no male present) is 30.6%, compared with 15.9% among male-headed households (no female present).

In his analysis of 14 countries in the EU, Wilfred Uunk (2004) documented a 24% decline in women’s median household income after divorce—comparable, he says, to the income change experienced by U.S. women after divorce. Uunk’s research revealed how median income declines were lower among divorced women from southern European countries (Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal) and Scandinavian countries (Demark and Finland), but higher among women from Austria, France, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom.

Declines in economic well-being also occur among women from previously cohabiting couples (Avellar and Smock 2005). Cohabiting couples have more precarious financial circumstances, experiencing lower personal and household incomes than married couples. After the dissolution of a relationship, the level of household income for cohabiting men declines 10%, but it declines 33% for cohabiting women. After the dissolution of a cohabiting relationship, women have a higher level of poverty than men, 30% versus 20%. Hispanic and African American women are more vulnerable than White women to experiencing economic decline. Cohabiting relationships may also include children affected by the same economic decline. These children are even more vulnerable, because cohabiting mothers have less access to their former partner’s income than divorced mothers do.

Marriage and Divorce Today

Violence and Neglect in the Family

Intimate Partner Violence

One of the myths mentioned at the beginning of this chapter is that the family provides a safe place for its members. This myth ignores the incidence of violence and abuse in families. Family violence is unique because the aggressor and the victim(s) are part of the same relational unit, with emotional bonds, attachments, and particular power dynamics (Breines and Gordon 1983).

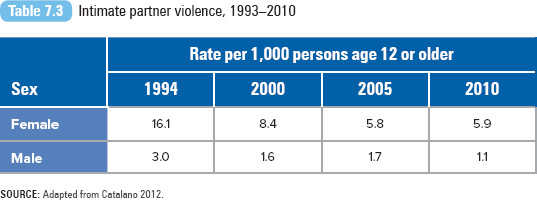

In the United States, nearly 25% of surveyed women and 8% of surveyed men reported that they had been raped or physically assaulted by a current or former intimate partner in their lifetime. Based on these estimates, approximately 1.5 million women and 835,000 men are raped or physically assaulted by an intimate partner annually in the United States (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). (Refer to Table 7.3 for Bureau of Justice Statistics data from 1994 to 2010.) Data confirm that violence by an intimate partner is a common experience worldwide. A review of more than 50 population-based studies in 35 countries revealed that between 10% and 52% of women reported that they had been physically abused by an intimate partner at some point in their lives (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2006).

Research has consistently linked specific social factors to family violence: low socioeconomic status, social and structural stress, and social isolation (Gelles and Maynard 1987). Feminist researchers argue that domestic violence is rooted in gender and represents men’s attempts to maintain dominance and control over women (Anderson 1997). Comparative data reveal how the severity and pattern of violence against women is higher in countries with high societal violence and low empowerment of women (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2006).

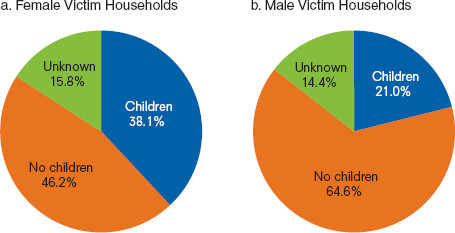

Studies have also documented how domestic violence is a significant predictor in maternal parenting behavior. Intimate partner violence involving a female victim often occurs in a household where a child is present (refer to Figure 7.1). According to Alytia Levendosky and Sandra Graham-Bermann (2000), psychological abuse, rather than physical abuse, is more likely to negatively affect a mother’s parenting, which in turn is related to children’s behaviors. The researchers report that a mother’s experience with psychological abuse is significantly related to a child’s antisocial behavior. Children in middle childhood begin to identify with the aggressor and act in emotionally aggressive ways toward their mothers. Yet female victims identify positive and negative impacts on their parenting from domestic violence (Levendosky, Lynch, and Graham-Bermann 2000). Battered women report that their emotional feelings or concerns make parenting difficult, noting the reduced amount of quality time or emotional energy they can devote to their children. But these women also report increased empathy and caring toward their children. Researchers suggest that battered women actively work to protect their children from the effects of violence in their household.

SOURCE: Adapted from Catalano 2012.

Figure 7.1 Percentage of households experiencing nonfatal intimate partner violence where children under age 12 resided, by gender of victim, 2001–2005

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics 2012.

Domestic Violence Victim Speaks

Child Abuse and Neglect

Some children are subject to abuse and neglect in their families. While physical, sexual, and emotional abuses are often identified, cases of neglect often go unnoticed. Physical abuse is defined as nonaccidental physical injury, from bruising to death; on the other hand, neglect is characterized by a failure to provide for a child’s basic needs (e.g., healthy regular meals), and it can be physical, educational (failure to enroll a school-age child in school, allowing chronic truancy), or emotional (spousal abuse in the child’s presence, permitting drug or alcohol use by the child, inattention to a child’s needs for affection) in nature (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2007).

The immediate emotional and behavioral effects of abuse and neglect—isolation, fear, low academic achievement, delinquency—may lead to lifelong consequences, including low self-esteem, depression, criminal behavior, and adult abusive behavior (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2006). In 2012, 686,000 children were victims of maltreatment. Most child victims, about 78%, suffered from neglect. The highest rates of victimization (per 1,000 children) were among ethnic minorities: African Americans (14.2%), American Indians or Alaska Natives (12.4%), and children of multiple races (10.3%). Tragically, about 1,640 children died as a result of abuse or neglect in 2012 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Administration for Children and Families; Administration on Children, Youth and Families; Children’s Bureau 2013).

Multiple factors related to the child, the parent or caregiver, the family structure, and the environment have been identified as contributing to child maltreatment. Though children are not responsible for being victims of maltreatment, certain factors make some children more vulnerable than others. For example, children with physical, cognitive, and emotional disabilities are at higher risk for maltreatment than other children. Infants and young children are vulnerable to particular forms of maltreatment, such as shaken baby syndrome. Teenagers are at greater risk for sexual abuse. Evidence indicates that abusing parents were victims of abuse and neglect themselves as children. Marital conflict, domestic violence, single parenthood, unemployment, and financial stress may increase the likelihood of maltreatment (Goldman et al. 2003). Poverty is consistently identified as a risk factor for child abuse. It is not clear whether the relationship exists because of the stresses associated with poverty or if reporting is higher because of the constant scrutiny of poor families by social agencies. Poor health care, lack of social and familial support, and fragmented social services have been linked with both poverty and child abuse (Bethea 1999).

Perfect Parenting?

Elder Abuse and Neglect

The elderly are also victims of abuse, usually when in the care of their older children and their families. Elder abuse can also occur within a nursing home or hospital setting. Federal definitions of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation first appeared in the 1987 Amendments to the Older Americans Act (National Center on Elder Abuse 2002a). Elder abuse can consist of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, neglect or abandonment, or financial exploitation. Domestic elder abuse refers to any form of maltreatment of an older person by someone who has a special relationship with the elder (a spouse, child, friend, or caregiver); institutional elder abuse refers to forms of abuse that occur in residential facilities for older people.

The number of U.S. adults aged 60 years or older is projected to increase from 35 million in 2000 to more than 72 million by 2030 (He et al. 2005). As the population ages, there will be an increased need for long-term care of the elderly, with spouses and adult children assuming the role of caretaker. An estimated 15 million individuals provide informal care to relatives and friends (Navaie-Waliser et al. 2002). Although caregiving can positively affect the physical and psychological well-being of care recipients, the added burden of elder care may strain the family’s and the caregiver’s emotional and financial resources.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study estimates that about 11% of older surveyed men and women reported experiencing at least one form of mistreatment (U.S. Department of Justice 2011). Elder abuse, particularly with family perpetrators, has been attributed to social isolation, personal problems such as mental illness or abuse of alcohol or drugs, and domestic violence (spouses make up a large percentage of elder abusers) (National Center on Elder Abuse 2002a). A major risk factor is dependency: abusers tend to be more dependent on the elderly person for housing, money, and transportation than are relatives who do not abuse (Lang 1993).

Elder Abuse

Teen Pregnancy and Newborn Abandonment

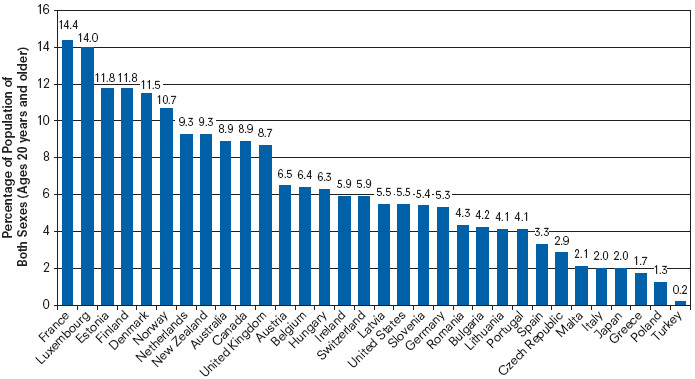

The U.S. teen birthrate is the highest in the developed world. The birthrate for teenagers (aged 15 to 19 years) declined from 1991 through 2012, falling from 62 live births per 1,000 teenagers in 1991 to 29.4 in 2012 (Martin et al. 2013). Despite the overall decline, birthrates for Black (47.3) and Hispanic (49.6) teens remain higher than for any other ethnic/racial group. The lowest rate was reported for Asian or Pacific Islander teens at 10.2 live births per 1,000 women (Martin et al. 2013). The U.S. teen birthrate has been attributed to a range of factors, from inadequate sexuality education to declining morals (Somers and Fahlman 2001). Research suggests that earlier or more frequent sexual activity among U.S. teens is not the cause of the higher birthrates; rather, sexually active American teens are less likely to use contraceptives than are their European peers (Card 1999; Kirby 2007). Jessica Silk and Diana Romero (2013, p. 1356) argue that cultural norms in the United States are “less open and supportive about sexual behavior among adolescents.” Though comprehensive sex education has been shown to be effective in reducing sexual risk-taking and negative social and health outcomes, it is denied to American youth for cultural reasons (Kirby 2007). The popular discourse on family values and framing sex education as a family matter has prevented health and human service providers and sexuality educators from delivering sex and health education to youth (Silk and Romero 2013). Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for more information on teen birthrates.

Heather Weaver, Gary Smith, and Susan Kippax (2005) noted that the number of births per 1,000 U.S. adolescents between the ages of 15 and 17 years was 8.5 times greater than in the Netherlands, 5.5 times greater than in France, and 3 times greater than in Australia. In contrast, the rate of contraceptive use at first intercourse was highest among Dutch (85%) and Australian (90% for males and 95% for females) teens, followed by French (74% and 77%) and U.S. (a minimum of 65%) youth. School-based sex education programs are mandatory in the Netherlands, France, and Australia. There are no federal laws in the United States that require sexual health education in schools.

Teen mothers, in comparison with their childless peers, are more likely to be poorer and less educated, less likely to be married, and more likely to come from families with lower incomes (Hoffman 1998). Their children often lag behind in standards of early development (Hoffman 1998); are less likely to receive proper nutrition, health care, and cognitive stimulation (Annie E. Casey Foundation 1998); and are at greater risk of social behavioral problems and lower intellectual and academic achievement (Hoffman 2006). Early childbearing also affects teen fathers. Teen fathers are more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors such as alcohol abuse or drug dealing. In addition, they complete fewer years of school and earn less per year (Annie E. Casey Foundation 1998).

Significant public costs are also associated with adolescent childbearing. For 2004, the estimated annual cost to taxpayers of births to young mothers was $9 billion, taking into consideration lost tax revenue, public assistance, health care for children, child welfare, and the criminal justice system (Hoffman 2006). Costs related to births to women 17 years old or younger were higher per birth than for those 18 to 19 years of age.

Although teenage childbirth has always been considered a social problem, reports of abandoned babies found in trash bins, restrooms, parks, and public buildings captures the public’s attention. The first case that caught national attention was “Prom Mom” Melissa Drexler. While attending her senior prom in 1997, Drexler gave birth to a full-term baby boy in a bathroom stall. She wrapped her baby in several plastic bags, left him in a garbage can, and returned to her prom. She pleaded guilty to manslaughter. There is no comprehensive national reporting system for abandoned babies.

Teen Pregnancy

Exploring social problems

Teen Birthrates

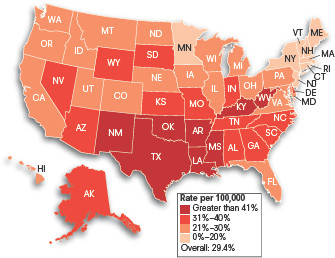

U.S. Data Map 7.1 Birthrates for teenagers aged 15–19, 2012 (per 1,000)

SOURCE: Martin et al. 2013.

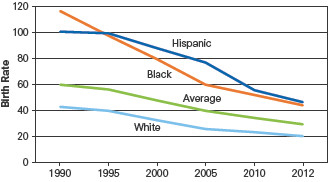

Figure 7.2 Birthrates per 1,000 females aged 15–19 by race/ethnicity, 1990–2012

SOURCE: Martin et al. 2013.

What Do You Think?

There is much geographic variation in teen birthrates. Overall, the lowest teen birthrates were in the Northeast, while rates were highest in the South. How does your state compare?

Historically, birthrates are higher among Black and Hispanic adolescent females than among White adolescent females (Figure 7.2). Although they have the highest teen birthrates, the rates for Black and Hispanic teens have had the most dramatic decline in recent years. After 2007, Blacks had the highest reduction, 41%, followed by Hispanics, with a 39% decline. The birthrate for White teens declined the least at 25%.

What social factors may have contributed to the decline in teen birthrates for each of these groups?

In Focus

Teen Parenting and Education

Pregnant teens and teen parents were routinely expelled from school until Title IX prohibited public schools from discriminating against them. High school graduation rates and college enrollment are lower for teen mothers than for those bearing children later in life, though some longitudinal research reveals that most teen mothers improve their education, income, and employment over time (Furstenberg 2007). Frank F. Furstenberg, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and S. Phillip Morgan (1987) found that teen mothers with the best life outcomes are those who have higher educational aspirations and better-educated and financially stable families.

In her longitudinal study, Lee SmithBattle (2007) examined the impact of parenting on 19 teen mothers’ educational goals and school progress. Contrary to popular belief, she observed the teens’ renewed commitment to their education. However, based on the accounts of the teen mothers, she discovered that “schools exacerbated their difficulties by failing to provide educational options or by enforcing policies that disregard their complex realities” (SmithBattle 2007:366). She writes,

Kali Gonzalez is pictured here with her daughter Kiah. Kali is a student at St. Johns State College. Researchers have found that teen mothers with the best life outcomes are those who had higher educational aspirations and better-educated and financially stable families.

© John Raoux/ /AP/Corbis

In addition to work demands, family responsibilities, and transportation difficulties, school policies and practices created additional barriers that undermined teens’ aspirations and hindered their school progress . . . continuing or remaining in school was complicated by cumbersome enrollment processes, stringent attendance policies, lack of educational options, and bureaucratic mismanagement.

Kate’s schooling was interrupted for a full year as a result of enrollment difficulties and limited-schooling options. When morning sickness led to many school absences early in her pregnancy, she was referred to the pregnancy school in her urban district. Because home tutoring was not offered as an option, she was forced to withdraw when enrolling in the pregnancy school proved insurmountable. . . .

Kate’s mother added that “we just gave up” when Kate’s home school failed to transfer her transcript to the pregnancy school in a timely manner. Jenna was also referred to the pregnancy program but refused to be transferred because of its poor academic reputation. She dropped out near the end of her pregnancy for a full year because homeschooling was not offered. As she said, “When I was 7 or 8 months pregnant, I stopped going to school. When the new semester started, I withdrew, because after the baby, I would have had to wait a certain amount of weeks to go back and then I’d end up failing. So it was no use.” . . .

[A] cascade of negative events, including inflexible school policies and disciplinary practices, landed Dawn, a suburban student, in educational limbo. After being homeschooled for several months, she returned to her senior year expecting to graduate with her class. She was eventually notified that she would not graduate because she had not completed assignments for one course, presumably because the teacher of that course had not relayed them to her homeschooling teacher. Deeply disappointed, Dawn resolved to return to school the following fall and take the few credits she needed to graduate. At the beginning of the fall semester, Dawn was driving her son to day care, going on to school, and leaving midmorning for work. Her plan to graduate at the end of the fall semester crumbled when the school principal revoked her parking privileges for a declining grade point average after a car accident led to the lack of transportation and several absences. Without a parking pass, Dawn could not drive her son to day care or go to work after school. She was thoroughly discouraged and lacked the skills and family support to appeal to the school board. Her student status was further complicated when she was kicked out of her home and moved in with her grandmother who resided in a different school district.

“I’m tryin’ to get into a school here in the city. But they’re tellin’ me that I have to go two semesters in order to graduate from this new school, when I only would have had to go one semester to graduate from my school. It’s just a mess . . . I actually want to go to school and they won’t let me because of something stupid.”

At her last interview, she was considering reenrolling in her suburban school so that she could complete the few credits she needed to graduate. Her plans seemed unrealistic because of the lengthy driving time involved (at least 30 to 40 minutes one way) and the complex scheduling that would be required with day care and an employer. (SmithBattle 2007:360–63)

SmithBattle (2007) concludes,

The gap between teen mothers’ aspirations and the support to achieve them suggests that educators and other professionals are missing a critical opportunity to promote teen mothers’ school-progress and their long-term educational attainment and success. Schools that cultivate teen mothers’ educational ambitions may ultimately contribute to positive chain reactions and the reduction of teen mothers’ prior adversity. (p. 369)

Explain how C. Wright Mills would define Kate’s experiences. Is she experiencing a private trouble or a public issue?

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from SmithBattle 2007.

The Problems of Time and Money

According to Beck (1992:89), “families . . . become the scene of continuous juggling of diverging multiple ambitions among occupational necessities, educational constraints, parental duties and the monotony of housework.” In a survey conducted by the Radcliffe Public Policy Center (2000), nearly all respondents reported feeling pressed for time in their lives, wanting to spend more time with their families, have more flexible work options, and even just have more time to sleep. In an analysis of couples in the eight EU countries, Tanja van der Lippe, Annet Jager, and Yvonne Kops (2006) concluded that work-home pressure was highest among couples from Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Even in Sweden with its family-friendly policies, couples felt the pressure to successfully combine paid work and family life, especially when negotiating long working hours and overtime.

Families with children must determine how best to provide financial support, while making sure their children have parental time. Suzanne Bianchi, John Robinson, and Melissa Milkie (2006) reported that in about 30% of families with children, both parents work full-time. Compared with their counterparts in other countries, a higher percentage of American dual-worker couples work long weeks (80 or more hours combined), leaving less family time during the week. Mothers still spend more time with children, an average of 13 hours per week compared with 7 hours per week for fathers. Mothers do most of the routine care (custodial daily care) of children, whereas fathers spend their time with children doing interactive activities (enrichment activities such as talking or reading to them) (Bianchi et al. 2006).

According to Lillian Rubin (1995), economic realities make it especially difficult for working-class parents to maintain their juggling act. In her book Families on the Fault Line, Rubin documented how structural changes in the economy undermine the quality of life among working-class families. This is a functional argument: Because the family is part of our larger social system, what happens at an economic level will inevitably affect the family. The reality of long workdays and workweeks does take its toll on families: the loss of intimacy between couples, the lack of time for couples and their children, tense renegotiations over household work, and juggling child care arrangements are just some of the issues that working families face.

Military family members outnumber military personnel by 1.4 to 1. In 2011, 726,500 spouses and more than 1.2 million dependent children lived in active-duty families (U. S. Department of Defense 2012).

REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton

Rubin’s study shed some light on the condition of working-class families, but often overlooked is the plight of lower-income families—too rich to be classified as living in poverty, but still too poor to be working class. In a two-year study, Lisa Dodson, Tiffany Manuel, and Ellen Bravo (2002) studied lower-income families in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Denver, Colorado; and Boston, Massachusetts. The researchers concluded that lower-income families deal with basic problems on a daily basis: managing the safety, health, and education of their children while staying employed. Lower-income parents are not “bad” parents; it’s just that their parenting may require more time and resources than they have. Among low-income families, there is a higher prevalence of children with chronic health issues or special learning needs; at least two thirds of the families in the Dodson et al. study reported having a child with special needs. These children require much more time and patience from their parents, sometimes jeopardizing parents’ ability to maintain employment and earnings. To support lower-income parents, the authors recommend comprehensive and flexible child care, along with workplace flexibility (taking time off work, adjusting their work schedule) (Dodson et al. 2002).

The Iraq and Afghanistan wars heightened our awareness of the difficulties associated with families separated by war. An estimated 1.2 million children live with military families, and approximately 700,000 of them have at least one parent deployed (Johnson et al. 2007). Research on the adjustment of children and adolescents of deployed military personnel indicates that the separation experience is stressful. Parental deployment has been linked with several negative youth outcomes, including depression (Jensen, Martin, and Watanabe 1996), behavioral problems (Levai et al. 1994), and poor academic performance (Hiew 1992). Boys suffer more effects of disruption than girls (Johnson et al. 2007). And as they are more aware of the risks involved in deployment, school-aged children experience anxiety and concern about the safety of the absent parent compared to younger children (Andres and Moelker 2011). More than 100,000 female soldiers who have served in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have been mothers. As reported by Lizette Alvarez (2009), the majority of deployed women are primary caregivers, and a third are single mothers like Army Specialist Jaymie Holschlag. While she was deployed in Iraq, Holschlag’s 10-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter lived with their grandparents. Concerned about the effects of her deployment on herself and her children, Holschlag requested a transfer when she returned home.

Military Families Cope With the Stress of War

Community, Policy, and Social Action

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993 was envisioned as a way to help employees balance the demands of the workplace with the needs of their families. The act provides employees with as many as 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave per year. It also provides for group health benefits during the employee’s leave. The FMLA applies to all public agencies and all private employers with 50 or more workers. To be eligible, employees must work at least 1,250 hours per year. In 2008, the FMLA was expanded to include families of wounded military personnel.

As of 2014, 11 states and the District of Columbia have enacted their own family and medical leave laws, extending the coverage provided by the FMLA or extending coverage to those not eligible under FMLA guidelines. In 2004, California became the first state to enact a law that provides paid family care leave. The California Family Rights Act allows employees to take paid leave to care for a child, spouse, parent, or domestic partner who has a serious health condition or to bond with a new child. Paid leave was extended to workers to care for a parent-in-law, grandparent, grandchild, or sibling in 2013. Employees who take such leave can receive 55% of their pay up to $1,067 per week for a maximum of six weeks. The California law applies to all employers, not just those with 50 or more employees (State of California, Economic Development Department 2014).

Although there is strong support for the FMLA and its stated goals, the act has also been criticized since its enactment. Almost 50% of workers are not covered by the FMLA because they work for private employers not covered under the law or small businesses employing fewer than 50 people. Though it has been used an estimated 100 million times, nearly two thirds of eligible workers have not taken advantage of the FMLA because they can’t afford the lost wages (National Partnership for Women and Families 2009).

Taking a World View

Parental Leave Policies

Rebecca Ray, Janet Gornick, and John Schmitt (2010) examined the generosity and the gendered structure of parental leave policies in 21 high-income countries. The researchers argue that the duration and benefit levels of parental leave policies are important because the policies

can shape the time that employed parents have to care for family members at home. In addition, leave policies can strengthen or weaken women’s labour market attachment, depending, to a large degree, on their design. Likewise, leave policies can influence men’s share in family caregiving, as policy rules affect the availability of leave for men and shape their incentives for take-up. (Ray et al. 2010:199)

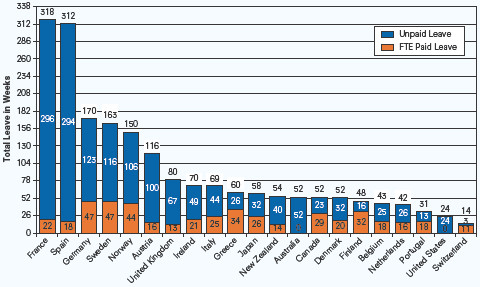

Ray et al.’s analysis reveals a range of leave policies for two-parent families, from 14 weeks in Switzerland to over 300 weeks in Spain and France (refer to Figure 7.3). The United States ranks 20th with 24 weeks. Switzerland ranks last, but provides 80% of a mother’s usual earnings during the parental leave period.

A second key dimension of parental leave is whether it is paid and, if so, how generously. For many low- and middle-income families, unpaid leave is not particularly helpful because families cannot afford the time away from work. The United States provides a striking example. According to a 2000 U.S. Department of Labor survey, for example, over a 22-month period in 1999 and 2000, 3.5 million people in the United States needed leave for family or medical reasons but did not take it; almost 80% of those who did not take the leave said they could not afford to do so.

Most countries provide between three months and one year of FTE (full time equivalent) paid leave. Denmark falls right at the middle of the paid-leave scale, guaranteeing about 20 weeks of FTE paid leave. No country provides more than one year of FTE paid leave, but Sweden and Germany each offer 47 weeks. Five other countries offer at least six months of FTE paid leave: Norway (44 weeks), Greece (34 weeks), Finland (32 weeks), Canada (29 weeks) and Japan (26 weeks). (Ray et al. 2010:203)

The researchers also note that Australia and the United States offer no paid leave to two-parent families.

What does the extent of parental leave coverage reveal about the social and familial values of each country?

Figure 7.3 Total and full-time-equivalent (FTE) paid parental leave for two-parent families, in weeks

SOURCE: Ray et al. 2010:203.

Community Responses to Domestic Violence and Neglect

Responses to domestic violence can be characterized as having a distinct community approach. In the area of child abuse, the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention established community-based children’s advocacy centers to provide coordinated support for victims in the investigation, treatment, prosecution, and prevention of child abuse in all 50 states. Programs at each center are uniquely designed by community professionals and volunteers to best meet their community’s needs. One such center is Project Harmony, based in Omaha, Nebraska. Project Harmony provides medical exams, assessment, and referrals. Project Harmony serves children who are victims of abuse and their nonabusing family members. By placing project staff and representatives from child protective services and law enforcement in the same facility, Project Harmony attempts to improve communication and coordination among all professionals involved in a child’s case. Refer to this chapter’s Voices in the Community feature to learn more about a rural support program based in Vermont.

Since its inception in 1995, the Office on Violence Against Women (VAW) has handled the U.S. Department of Justice’s legal and policy issues regarding violence against women. The office offers a series of program and policy technical papers for individuals, leaders, and communities to support their efforts to end violence against women. These papers highlight some of the best program models and practices and were produced by the Promising Practices Initiative of the STOP Violence Against Women Grants Technical Assistance Project (Little, Malefyt, and Walker 1998). Two featured programs, still operating in 2014, are the following:

- The Minnesota Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (DAIP) was developed in 1980 and serves as a national and international program model. It was the first program of its kind to coordinate the intervention activities of each criminal justice agency in one city. The goals of the program include victim safety, offender accountability, and changes in the climate of tolerance toward violence in the Duluth community. The program also offers a men’s nonviolence education program, a national training and technical assistance program, and a victim advocacy program for Native Americans through the Mending the Sacred Hoop project.

- The Women’s Center and Shelter (WC&S) of Greater Pittsburgh was founded in 1974. WC&S coordinates its program efforts with the medical community, criminal justice agencies, and other organizations. The programs focus on the ability of women to take control of their own lives. WC&S provides comprehensive victim services, which include parenting education and legal and medical advocacy. WC&S has also created a school-based curriculum called Hands Are Not for Hurting. The curriculum uses age-appropriate lessons that encourage nonviolent conflict resolution and teach youth that they are responsible for the choices they make.

The National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA) believes that community education and outreach are important in combating the problem of elder abuse and neglect. The NCEA supports community “sentinel” programs, which train and educate professionals and volunteers to identify and refer potential victims of abuse, neglect, or exploitation. In 1999, the NCEA established partnerships with the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), the Meals on Wheels Association of America (MOWAA), and the National Association of Retired and Senior Volunteer Program Directors. These organizations were selected because of their unique access to isolated elders in their homes. The NCEA funded six coalition projects in Arizona, California, New York, North Carolina, and Utah. The program trained more than 1,000 professionals and volunteers to serve as sentinels; as a result, there was an increase in the number of abuse referrals in communities where sentinels were used. Administrators also noticed an increase in the level of satisfaction among volunteers, who as a result of the project were able to assist individuals who they believed might be victims or potential victims (National Center on Elder Abuse 2002b).

Voices in the Community

Wynona Ward

Wynona Ward thought she had left her violent childhood behind her. But in 1991, when her sisters called to inform her that their brother Richard had raped a child in the family, she was not surprised. The child had also been raped by her grandfather—Ward’s father—years earlier. Ward describes Richard as “living up to his father’s expectations. He was expected to grow up to be a child abuser” (quoted in Jetter 2000). Ward, her mother, and her siblings were subjected to years of sexual and physical abuse by her father. She and other family members supported the victim during her brother’s trial and subsequent incarceration. The experience motivated Ward to enroll in law school, and after graduating from Vermont Law School, Ward established Have Justice Will Travel, a mobile law office serving battered women in Vermont.

Driving more than 30,000 miles a year, Ward is able to reach victims who otherwise would not have access to legal or social services. With her mobile office (her truck is equipped with a radio, scanner, computer, and printer), Ward brings support and hope to women who have none. The group also provides transportation to and from court hearings and free legal representation. Ward says, “[We] work with these women so they can become strong and independent and self-reliant and be able to support themselves and their children” (as quoted in Brown 2010).

Since 1998, Have Justice Will Travel has assisted 10,000 victims with legal and social services. From its humble start at Ward’s kitchen table, the program has expanded to three locations with the assistance of staff and student volunteers from Ward’s alma mater, Dartmouth College, and other local colleges. Ward divides her time on the road between working with clients and writing grant proposals to support the program. Growing her program to serve more women and their families continues to be her goal.

Everyday [sic] in this country, we have more and more women that are working in social services, more women that are entering the legal field, more people that can have empathy for victims. . . . Different donors have asked me, “well, how are you going to expand Have Justice?” There’s only one Wynona. But I say to them, “no, you’re wrong. There are many Wynonas out there.” (Ward 2002)

How effective is Have Justice Will Travel? Does the program address the problem at an individual or structural level?

Teen Pregnancy and Infant Abandonment

From an interactionist perspective, sex education has been framed as a private, family issue. There are no U.S. federal laws that require sexual health education in schools. According to health professionals and educators, this framework has denied young men and women access to basic sex education information and services (Silk and Romero 2013). As a result, sexual health education has been defined as the responsibility of social and health service programmers. In the 1980s, these programmers defined prevention as an effective way to address the problems of teen pregnancy and parenthood (Card 1999). In the 1990s, several new prevention approaches emerged, particularly after the passage of the Welfare Reform Act of 1996. Under Section 905 of the act, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was mandated to ensure that at least 25% of all U.S. communities had teen pregnancy prevention programs in place. Most states identified target goals related to teen birthrates.

Curriculum-based sexual health education programs are categorized into two groups (Kirby 2007). The most prominent form, abstinence-only programs, promotes abstinence from sex and not condom or other contraceptive use. Comprehensive programs promote abstinence along with condom and other contraceptive use. Programming in both groups may vary. For example, some abstinence programs emphasize abstinence until marriage, while others do not. Some comprehensive programs feature only an educational component, while others include contraceptive services.

In his review of abstinence-only program evaluations, Douglas Kirby (2007) noted that only a small number of abstinence programs have been evaluated. He concluded, based on the limited research, that there was little evidence to suggest that any particular abstinence program delays the initiation of sex. Kirby found that comprehensive programs were more likely to have a positive impact on teen sexual behavior—at least 40% of the programs resulted in increased condom and contraceptive use. Researchers also documented increased abstinence, reduced numbers of sexual partners, and delayed initiation of sex among students participating in comprehensive programs.

In response to newborn and infant abandonment, since 1999 all states have passed laws that offer safe and confidential means to relinquish unwanted newborns without the threat of prosecution for child abandonment. State laws vary according to the child’s age (72 hours to 1 year old) and the personnel or places authorized to accept the infant (hospital personnel, emergency rooms, church, and police).

It is unclear how effective these safe-surrender or safe-haven laws have been in reducing infant abandonment or death. New Jersey, home of the first infant abandonment case that gained national attention, passed a safe-haven law in August 2000, modeled after Texas 1999 legislation. Between August 2000 and November 2003, New Jersey officials assisted 17 babies. These children were adopted, placed in foster care, or returned to their mothers (New Jersey Safe Haven Protection Act 2007). In 2006, however, six dead newborns were found abandoned in New York, despite the state’s safe-haven laws. Critics argue that the state’s safe-haven laws were poorly advertised, with most residents not knowing about the laws’ provisions. In Illinois, a discussion of the safe-haven law is included in the high school health curriculum, possibly ensuring more awareness among high-risk youth (Buckley 2007).

In 2007, a mother abandoned her 3-month-old baby boy at a neonatal clinic in Rome, Italy. She was the first to use Casilino Polyclinic’s modern foundling wheel. The original foundling wheel, used in the Middle Ages, was a revolving wooden barrel built into the church’s exterior wall; the mother could deposit her baby and turn the wheel, and the baby would be safely protected inside the church. The Rome clinic uses a small modern structure equipped with a heated cradle and a respirator. Also available at other Italian hospitals and churches, these structures are equipped with an alarm to alert medical or church staff when a child is deposited. Foundling wheels or designated drop-off locations for unwanted newborns are used in other countries such as Germany, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic (Povoledo 2007).

Supporting Different Family Forms

According to sociologist David Popenoe (1993), there has been a serious decline in the structure and function of the family since the 1960s. Families are not meeting society’s needs as they once did and have lost most of their “functions, social power and authority over their members” (Popenoe 1993:527–28). He attributes the weakening of family function to high divorce rates, declining family size, and the growing absence of fathers and mothers in their children’s lives. Data reviewed at the beginning of this chapter—the declining percentage of nuclear families, along with the increase in single-parent families and nonfamily households—lend support to his observation.

But critics of Popenoe’s position argue that the family-in-decline hypothesis relies too heavily on the definition of family in its nuclear form (Bengston 2001). Sociologist Judith Stacey (1996) agrees that the “family” as defined by a nuclear form of mom, dad, and children is in decline. This family system has been replaced by what Stacey calls a postmodern family condition, one characterized by diverse family patterns and forms, where no single family form is dominant. There have been significant changes in the traditional family’s structure and functions (Bengston 2001); modern families are best characterized by their diversity (Hanson and Lynch 1992). Indeed, “a single, all-encompassing definition of ‘family’ may be impossible to achieve” (Erera 2002, p. 3).

The proportion of nuclear families is decreasing and being replaced with family structures that include single-parent, blended, adoptive, foster, grandparent, and same-sex-partner households (Copeland and White 1991). The increasing diversity of American families requires that we broaden our research and policy agendas beyond traditional family forms (Demo 1992). Perhaps one solution to the “problem” of families is to appreciate and embrace other family forms. Let’s examine two family forms: cohabitation and grandparents as primary caregivers to grandchildren.

Cohabitation

Larry Bumpass (1998) argues that the increase in cohabitation reflects and reinforces the declining significance of marriage as a life course marker in our society. He reports that almost half of the young adults in the United States have lived in a cohabiting union at some point in their lives, a trend reflected in most Western societies. Cohabiting is defined as sexual partners not married to each other but residing in the same household.

There were nearly 7.5 million cohabiting (opposite-sex) couples in 2010 (Kreider 2010). A quarter of unmarried women aged 25 to 39 are currently living with a partner, and an additional quarter have lived with a partner sometime in the past. According to the National Marriage Project (2009), cohabitation is more likely to occur among those of lower educational and income levels and among those who are less religious than their peers and who experienced parental divorce or high levels of marital discord during childhood. The pattern is particularly true for Black, Hispanic, and mainland Puerto Rican women compared with White women (Bumpass and Lu 2000). Cohabitation rates have increased among Black and White adults; higher increases have been observed among Whites. Larry Bumpass and Hsien-Hen Lu (2000) report that for women aged 19 to 44 years, 59% of high school dropouts have cohabited compared with 37% of high school graduates.

Data on the proportion of households cohabiting for selected countries are presented in Figure 7.4. In 11 European countries, cohabiting partners have the possibility of entering a civil union (via registration) other than marriage. In other countries, cohabiting couples who have not registered their union, but have lived together for a specific period of time, are considered to have the same legal rights and obligations as married couples or partners who have formalized their relationships. For example, in Australia and New Zealand, couples living together for a specific period of time are legally considered to be in a partnership with status equal to marriage (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2010). Many countries have responded to the increasing number of cohabitating couples by expanding their rights and legal recognition.

Figure 7.4 Percentage of cohabiting households

SOURCE: Adapted from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2009.

Researchers acknowledge that not all cohabitations will eventually lead to marriage and may instead serve as alternative forms of marriage (Manning and Smock 2002), though marriage still represents the cultural ideal, signaling a higher level of commitment. For many, cohabitation is considered a pathway to marriage. The percentage of marriages that began as cohabitating relationships rose from 41% in the early 1980s to 65% of marriages between 1995 and 2002 (Manning and Jones 2006).

Dafoe Whitehead and Popenoe (2005) cite a study that concluded that premarital cohabitation, when limited to a woman’s future husband, was not associated with an elevated risk of divorce. Conversely, they observe, “No evidence has yet been found that those who cohabit before marriage have stronger marriages than those who do not.” For data collected in 2002, the probability of a woman’s marriage lasting 10 years if she had cohabitated before marriage was lower than the probability of a woman’s marriage lasting the same amount of time if she did not cohabit before marriage, 61% versus 66% (Goodwin, Mosher, and Chandra 2010). However, the difference between the two groups is not significant. If a couple were engaged when they began cohabiting, the probability that the woman’s marriage would survive 10 years was similar (65%) to the probability for couples who did not cohabit at all (66%) (Goodwin et al. 2010).

The increase of cohabitation has coincided with the increase in unmarried childbearing—more than 40% of cohabiting couple households contain children (National Marriage Project 2013). Though data indicate that about two fifths of all children will live with their mother and a cohabiting partner and that about a third of the time children spend with unmarried mothers is spent in a cohabiting relationship, family scholars acknowledge that more needs to be known about the impact of cohabitation on the family experiences and life outcomes of these children (Bumpass and Lu 2000).

Non-Traditional Families

Grandparents as Parents

Fifty-nine-year-old Pat and Ken Owens of Lewistown, Maryland, are the primary caretakers of their grandchildren, Michael and Brandi (Armas 2002). Pat and Ken are among the 2.7 million grandparents raising their grandchildren. According to U.S. Census, in 2012, White children were more likely than children of other ethnic/racial groups to live in a grandparent’s household with or without a parent present (Ellis and Simmons 2014). The role of grandparents as primary guardians to grandchildren has not been addressed in many other countries. In the United Kingdom, a study of 870 grandparents revealed that only 0.5% had custodial care of their grandchildren, while 61% were their grandchild’s regular day care provider (Clarke and Roberts 2004).

Grandparents may assume caretaking responsibilities when parents are unable to live with or care for their children because of death, illness, divorce, incarceration, substance abuse, or child abuse or neglect. The HIV/AIDS epidemic has been identified as a significant contributor to African American grandparents assuming primary parenting roles (Crewe 2012). Pat and Ken Owens have not heard from Michael and Brandi’s mother in the past two years and only recently began receiving financial support from Michael’s father. The alternative for their grandchildren would have been foster care, something that Pat Owens did not want to happen: “I don’t want to make it sound like it’s easy because there are some tough, tense times. But I’m very proud of the fact that all the grandchildren still play together and go to school together” (Armas 2002:A6).

Research identifies how grandparents who care for their grandchildren are at high risk for emotional and physical distress. This distress is related to a deficit of social resources, such as marital status, social support, economic resources, and the demands of the caregiving role itself. Grandparent caregivers are more likely to experience depression and suffer from fair to poor physical health and activity limitations than are grandparents in more traditional roles (Chase Goodman and Silverstein 2006). Counseling and the use of school programs (tutoring and special education) provide grandparents and grandchildren some emotional and academic support (Trail Ross and Aday 2006; Kelch-Oliver 2011). Despite the negative consequences, grandparents also report satisfaction and rewards related to caring for their grandchildren.

The sudden responsibility for children leaves many grandparents on fixed incomes with unexpected financial burdens. In one study, children living in a grandparent’s household without a parent present were twice as likely to be living below the poverty level as were children living with both grandparents and a parent. Children who lived with just their grandparents were also at risk of not being covered by health insurance (Fields 2003). If eligible, grandparents can get assistance through HHS Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Some states, such as Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, offer guardianship or kinship care subsidy programs for grandparents.

Emotional and social support is available for grandparent-headed households. Local grandparent support groups are listed by organizations such as AARP, Generations United, and GrandsPlace. These organizations also provide fact sheets, community links, and suggestions for clothing and school supplies, recipes, and travel and activity guides for grandparents and their grandchildren. AARP (2002) has recognized several model support programs such as the Kinship Support Network in San Francisco, California; Project Healthy Grandparents in Atlanta, Georgia; and Grandma’s Kids Kinship Support Program in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Sociology at Work

Paralegals and Legal Assistants

Carlos Sandoval—Class of 2013

Undergraduate Major: Sociology Undergraduate Minor(s): Philosophy, Religion

Paralegals and legal assistants do a variety of tasks to support lawyers in law firms, corporate legal departments, and government agencies. Many law firms utilize paralegals and legal assistants in an attempt to lower their expenses and billing costs to clients and to increase the efficiency of their legal services (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014). Though Carlos Sandoval initially wanted to work for a police department or correctional facility, after graduating he was hired as a legal assistant for a county prosecutor’s office. He is currently assigned to the Family Support Division doing mostly clerical work, interacting with clients, organizing files and documents, scheduling hearings, and mailing out notices for court dates.

There are many ways to become a paralegal or legal assistant. Some community colleges offer an associate’s degree in paralegal studies, though law firms hire college graduates with a bachelor’s degree (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014). Previous work experience is preferred, but not necessary. During Carlos’s job interview, sociology helped him address his lack of job experience:

Having minimal work experience, it is hard to talk about what skills you have or how you can apply your previous experience to this new job. That being said, as soon as I walked into the interview, I tried to apply sociology to every question I was asked. This allowed me to continue talking about any particular subject with confidence. For example, one of the questions asked was “How do you feel with working with minority groups and groups from lower income families?” I began by explaining what I know about groups in poverty and minority groups and how they may be less fortunate than others and not have all the resources they may need. I don’t remember much from the interview, but I do remember having used sociology in each of my answers.

Carlos credits his internship experiences at a juvenile detention center and at a child protective services office with helping him develop work experiences with clients and confidential cases. He says,

Although they may have not been related to my job now, my previous employers gave excellent references for my work ethic and skills. At the end of the day, all an employer wants is a good worker and someone they can see themselves working with. I believe it was my interview and references that gave me this job.

Carlos offers the following career and job search advice for undergraduates:

The first advice I would give is to do as many internships and volunteer positions as you can for the field you are trying to work in. Even if the job is not directly relatable, the reference you will receive from doing good work is truly invaluable. This also allows you to experience different fields and find out which is right for you. Next I would say apply for as many jobs as possible. Many employers take a long time to hire someone. Even though it feels like everyone is rejecting you, employers will begin to call back all at the same time. Also, visit any and all preparedness workshops, if they are available. Especially for government jobs with standardized tests, there are workshops and practice tests that are available; people often fail for simply not studying.

Chapter Review

- 7.1 Describe how the sociological perspectives explain social problems related to the family

From a functionalist perspective, social problems emerge as the family struggles to adapt to a modern society. From the conflict theorist, the family is a system of inequality where conflict is normal. Conflict can derive from economic or power inequalities between spouses or family members. From a feminist perspective, inequality emerges from the patriarchal family system, where men control decision-making in the family. According to an interactionist, we create and maintain our definition of a family through social interaction. This process affects our larger social definition of what everyone’s family should be like and the kind of family that we create for ourselves.

- 7.2 Summarize the effects of divorce on children

In general, the research indicates that children with divorced parents have moderately poorer life and educational outcomes (emotional well-being, academic achievement, labor force participation, divorce, and teenage childbearing) than do children living with both parents. Research also suggests that marital separation is beneficial to the well-being of children. Divorce is less disruptive if both parents maintain a positive relationship with the child, if parental conflict decreases after separation or divorce, and if the level of socioeconomic resources for the child is not reduced.

- 7.3 Identify why the U.S. teen pregnancy rate is the highest in the developed world