Chapter 6 Age and Aging

Learning Objectives

- 6.1 Explain how age is both a biological and a social classification

- 6.2 Identify the causes of population aging

- 6.3 Describe how the sociological perspectives address age, aging, and inequality

- 6.4 Explain how age serves as a basis for prejudice or discrimination

- 6.5 Examine the characteristics of young and older voters

More than 500 retired scientists and researchers volunteered as first responders to the nuclear plant accident at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant in 2011. The Skilled Veterans Corps volunteers ranged in age from 60 to 78 years. According to Yasuteru Yamada (pictured to the right), a retired physicist, “young workers who may reproduce a younger generation and are themselves more susceptible to the effects of radiation should not be engaged in such work. This job is a call for senior citizens like me” (quoted in Glionna 2011a). The story of Yamada and his colleagues was characterized as “a lesson about growing old gracefully, about demonstrating the sheer willfulness in an aging body” (Glionna 2011b). Yamada maintains that he is nobody’s hero. Despite their expertise and their willingness to help, the volunteers were not permitted to assist with the cleanup.

Age is both a biological and a social classification (McConatha et al. 2003). There are social dictates regarding age—socially and culturally defined expectations about the meaning of age, our understanding of it, and our responses to it (Calasanti and Slevin 2001). We make a fuss over the 77-year-old Ironman triathlete and the 13-year-old college student because they are unexpected or deemed unusual for people of their age. Age distinguishes acceptable behavior for different social groups. Voting, the legal consumption of alcohol, military enlistment, and the ability to hold certain elected offices (you can’t be president of the United States until you are at least 35 years old) are examples of formal age norms. Informal age norms also demonstrate how a society defines what is considered appropriate by age (Calasanti and Slevin 2001).

Age is both a biological and a social classification. Active seniors expand our beliefs and expectations of elderly behavior and roles.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/The Christian Science Monitor/Getty Images

Sociologists examine age and the process of aging through a life course perspective. This perspective examines the entire course of human life from childhood, adolescence, and adulthood to old age. The life course perspective tends to view “stages of life” as social constructions that reflect the broader structural conditions of society (Moody 2006). Aging occurs within a social context: one’s social class, education, occupation, gender, and race will determine how one experiences adolescence or old age. However, there is also room for individuals to make their own choices in interpreting or embracing age-related roles (Moody 2006). Gerontology is the specific study of aging and the elderly, the primary focus of this chapter.

Our Aging World

Much has been written about the graying or aging of America, a change in our demographic structure referred to as population aging (Clark et al. 2004). One way to confirm population aging is to look at the median age of the U.S. population. (The median age is the age where half the population is older and the other half is younger.) The median age was 17 years in 1820 and 23 years in 1900, and by 2000 it had increased to 35 years. By 2030, the median age is predicted to increase to 42 years.

Demography is the study of the size, composition, and distribution of populations, and demographers have identified several reasons for population aging. First, population aging is caused by a decline in birthrates (Moody 2006). With a smaller number of children, the average age of the population increases. In 1900, America was a relatively young population, with children and teenagers making up 40% of the population. By 1990, however, the proportion of youth had dropped to 24%.

Population aging can also occur because of improvements in life expectancy as a result of medical and technological advances (Moody 2006), improved access to health care, healthier lifestyles, and better health before 65 years of age (National Center for Health Statistics 2009). As people live longer, the average age of the population increases. In 1900, life expectancy at birth was 47 years; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the life expectancy for a child born in 2011 is 78.7 years (National Center for Health Statistics 2009; Hoyert and Xu 2012).

Longer life expectancy has also made it necessary to redefine what it means to be old or elderly. Gerontology scholars and researchers now make the distinction between the young-old (aged 65 to 75), the old-old (aged 75 to 84), and the oldest-old (aged 85 or older) (Moody 2006). Unless noted otherwise, the use of the term elderly in this chapter will refer to those aged 65 years or older.

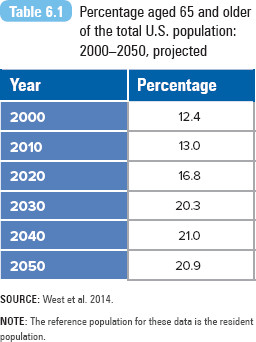

Finally, the process of population aging can be influenced because of birth cohorts (Moody 2006). A cohort is a group of people born during a particular period who experience common life events during the same historical period. For example, the Depression of the 1930s produced a small birth cohort that had a minimal impact on the average age of the population. However, the baby boom cohort after World War II is a very large cohort, and its middle-age baby boomers will contribute to the aging of the U.S. population. When Kathleen Casey-Kirschling, our nation’s first baby boomer, born January 1, 1946, applied for her Social Security benefits in 2007, Social Security commissioner Michael Astrue said it signaled “America’s silver tsunami” (Ohlemacher 2007:A1). An estimated 10,000 people a day will become eligible for Social Security benefits during the next two decades (Ohlemacher 2007). Graphically, the aging of the United States is displayed in Table 6.1. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau dramatically show the effect of the baby boom generation on the overall age structure.

SOURCE: West et al. 2014.

NOTE: The reference population for these data is the resident population.

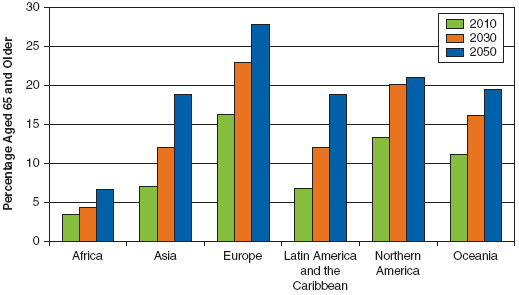

Demographers predict that the number of Americans aged 65 years or older will increase over several decades. To provide a context for aging in the United States, it is helpful to examine trends in the rest of the world (He et al. 2005). Populations are aging in all countries, though the level and pace vary by geographic region. Fertility decline, improved health and longevity, and increasing urbanization have contributed to the unprecedented growth of older populations throughout the world. In 2008, 506 million people (7%) in the world were 65 years old or older; by 2040, the number is projected to increase to 1.3 billion (14%). By 2020, for the first time, people aged 65 or over are expected to outnumber children under age 5.

Figure 6.1 reports the percentage of elderly in the population from 2010 and projected through 2030 and 2050. Europe and Northern America will continue to have the highest percentage of elderly in the world. The percentage of elderly in Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean are predicted to more than double due to high fertility and low mortality rates. In less developed countries, though the proportion of the elderly is low, the number of elderly is large due to the size of their populations. In India, there were 63 million older people, representing only 5.3% of the population (West et al. 2014).

Figure 6.1 Percentage aged 65 and older of the total population for each world region: 2010, 2030, and 2050.

SOURCE: West et al. 2014.

Gerontologist Harry Moody (2006) warns, “Population aging is a long-range trend that will characterize our society as we continue into the 21st century. It is a force we all will cope with for the rest of our lives” (p. xxiii). Population aging means an increase in the number or proportion of elderly and signals the need for changes in health care, employment status, living arrangements, and social welfare for the elderly and the rest of society.

The aging of U.S. society is likely to transform state, regional, city, and suburban populations. A 2007 Brookings Institution report (Frey 2007) predicts the emergence of two major senior populations, each with a set of specific needs and geographic impacts. “Yuppie senior” affluent populations are expected to emerge in the South and West (in cities such as Las Vegas, Denver, Dallas, and Atlanta), increasing their demands for new types of community cultural amenities. Their affluence will continue to support and encourage the economic and civic growth of their geographic areas. Conversely, cities in the Northeast and Midwest are predicted to have a disproportionately higher population of “mature seniors”—less financially stable or physically able than yuppie seniors. Mature seniors are likely to require more social and public support programs, along with affordable private and institutional housing and accessible health care providers (Frey 2007), ultimately leading to competition over resource allocation such as funding for schools versus senior services.

Age and Society

United States Population Pyramid

Taking a World View

Aging in China

The growth of the older population in China is expected to accelerate in the next 50 years, surpassing the aging population in many Western European countries and the United States. Charles Kincannon, Wan He, and Loraine West (2005) report that more than a half century ago, 1 in 25 Chinese people was aged 65 years or older, but by the beginning of the 21st century, 1 in every 14 Chinese was an older person.

According to population projections by the U.S. Census Bureau’s International Programs center, China’s older population will quadruple. Given China’s total population of over 1.2 billion in 2000, this accelerated aging process will involve huge numbers of people. By 2050, it is projected that there will be 349.0 million people 65 years old or older in China, almost one fourth more than the total population of the United States in 2000 (Kincannon et al. 2005:245). (In contrast, the 2050 projection for the number of elderly in the United States is 33.7 million.)

Elderly Chinese rely on a variety of sources for financial support. In 2000, just over half the Chinese men aged 65 years or over who were no longer working relied primarily on their family for financial support, while 4 in 10 received primary support from a retirement pension. Older women were far more likely to be dependent on their families for support—82%—and much less likely to rely on a retirement pension—13% (Kincannon et al. 2005:250).

Reliance on family support is greatest among the oldest-old Chinese population, largely because they are not eligible to receive benefits under China’s pension system (first established in the 1950s and limited to those with at least 20 years of employment) or, if they do qualify, because pension benefits are insufficient to use as the primary source of financial support.

The researchers predict that as China expands its system of social insurance programs, reliance on family support is likely to decline. Since the 1990s, China’s government policies have expanded community social services for the elderly. Community-based in-home care has gained popularity in urban areas. In this model of care, the elderly receive supplemental or respite care at home if their children work and are unable to care for them or if their children do not live with them (Xu and Chow 2011).

The progressive aging of its older population is a serious issue for China. Better medical care and health conditions in China have led to longer lives for older people in the country. As Kincannon et al. (2005) observe,

over time, a nation’s older population may grow older on average as a larger proportion survives to 80 years and beyond (the oldest old). The oldest old and the young old have very different economic, demographic, and health statuses, thus they also have very different needs for health services, old-age care, residential arrangements, or assistance with the requirements of daily life. The oldest old are more likely to be widowed (especially the oldest-old women), to be frail or sick, and to be unemployed and lack financial resources. Their needs may put tremendous pressures on their families as well as on society. The oldest old, therefore, are a group within the older population that warrants special attention. (p. 245)

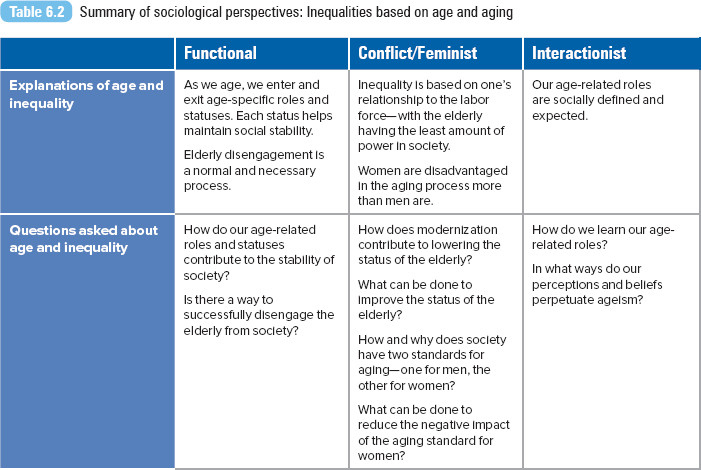

Sociological Perspectives on Age, Aging, and Inequality

Functionalist Perspective

Age helps maintain the stability of society by providing a set of roles and expectations for each particular age group or for a particular life stage. These roles are reinforced by our major social institutions—education, the economy, and family. We assume that children, 18 years old or younger, should be in school. After high school graduation, young adults have the choice of entering the workforce or continuing their education (where their student role continues), whereas adulthood is a time set aside to build one’s career and to begin a family. Retirement is another important age-related stage, with societal roles and expectations for a retired person.

Consider how each age group has its own function or role—the young attend school preparing for their adult lives, adults are employed and building their lives, and the elderly retire. Disengagement theory defines aging as a natural process of withdrawal from active participation in social life. Older people disengage from society (from their work and certain parts of their lives), and in turn, society disengages from them (Turner 1996). The theory contends that people enter and exit a set of roles throughout their lives. These transitions are natural and functional for society (Mabry and Bengston 2005; Moody 2006).

This process is portrayed as orderly, timely, and necessary for the well-being of the entire society. For example, in the workplace, older workers must relinquish their jobs to make room for younger workers in the labor market. This process is socially supported through retirement plans, pensions, and Medicare (Mabry and Bengston 2005). Disengagement is portrayed as positive for the elderly because it enables them to participate in activities and a lifestyle that earlier would not have been possible (they may become more fully engaged in community, family, or leisure activities). The final form of disengagement is death.

However, this perspective fails to acknowledge how vulnerable and powerless adults are in their older years. Is this disengagement natural or forced by society? The next perspective answers this question.

Healthy Lifestyles

Conflict Perspective

The modernization theory of aging suggests that the role and status of the elderly declines with industrialization. Specifically, their power, wealth, and prestige are linked with their labor contribution or relationship to the means of production. In hunting and gathering societies, the elderly had a low status because they were unable to contribute to the primary means of production. However, their status increased during the time of stable agricultural societies, when older people controlled land ownership. In modern industrial society, life experience is surpassed by technological expertise; thus, the status of the elderly declines.

From a conflict perspective, the two groups at odds with one another are the young and the old. As Donald Cowgill (1974) explains, society systematically advantages the young, supported by what he calls the “cult of youth”—a value system that glorifies youth “as a symbol of beauty, vigor and progress and discriminates in favor of youth in employment and in the allocation of community resources” (pp. 15–16).

Cowgill (1974) identifies how four aspects of modernization lower the status of older people. The first is health technology. Modern health advances improve the population’s overall health and longevity. This creates an older and healthier workforce, willing and able to stay in the labor force a bit longer: “As the lives of workers are prolonged, death no longer creates openings in the labor force as it once did” (Cowgill 1974:12). Society then creates a new opening through retirement, forcing people out of their most valued and senior roles in the labor force. Elderly workers are reduced to retirement status with less income and influence.

The modernization theory of aging suggests that the declining status of the elderly is associated with their decreasing economic and labor contribution. What status do we attribute to the position of store greeter? High or low?

J.D. Pooley/Getty Images

The next two aspects, education and economic technology, are related to one another. In a modern society, the young have more opportunities to acquire education and training. The status of younger members of society is elevated because they become more literate than their parents. Society relies on their increased literacy in the workplace, creating new information- and technology-based occupations. The people most qualified for these positions are the younger, more literate workers. Older workers perform more traditional jobs, some that are less valued or that eventually become obsolete.

The final aspect is urbanization. A modern society is more urban, characterized by increased social mobility and migration. Cowgill (1974) argues that the young migrate more than the old do. The migration produces a physical and emotional separation between a child and the family of origin, tearing down the bonds of the extended family. Yet it also promotes the cultural image of the young moving to something better, while the old are left behind.

Researchers have challenged the assumption that modernization and economic conditions automatically lead to the status decline of the elderly. Sociologists and anthropologists have documented how the status of older persons varies by race and ethnicity, gender, culture, and social class. Among Hispanics and Asians, where multigenerational households are common, the elderly are respected and honored.

Feminist Perspective

Women constitute the majority in the U.S. older population. In 2010, there were 23 million women aged 65 years or older, compared with 17 million men (U.S. Census Bureau 2012). Women outnumber men in the older population at every single year of age from 65 to 100 years and over (Werner 2011). The standards of our culture create more problems for women than for men as they transition into their middle and later years. Women seem more vulnerable to societal pressure to retain their youth and, consequently, face more questions about their self-worth, which may lead to serious problems ranging from low self-esteem to depression (Saucier 2004). Questions about self-worth and value are also raised in the workplace, where researchers have documented how women experience greater age discrimination during all ages than do men (Duncan and Loretto 2004). In many ways, aging is socially constructed through a gendered lens.

Susan Sontag (1979) notes how society is much more permissive about aging in men. She writes about the double standard of aging—men are judged in our culture according to what they can do (their competence, power, and control), but women are judged according to their appearance and beauty. Women’s identity is more closely associated with their physical appearance than is the identity of men. As a result, society considers men distinguished in their old age, but women must disguise the fact that they are aging. Sontag argues that because women are unable to maintain their youthful looks as they age, they are pressured to defend themselves against aging at all costs.

Feminist scholars argue that the cosmetic industry focuses on a male and youth standard. Though cosmetic products are advertised for women’s use (ever notice that there are no male cosmetics counters at your department store?), feminists assert that the industry is responding to the male-defined standard of female beauty. In addition, the industry is responding to the image of unattainable youthful beauty upheld by society (Calasanti, Slevin, and King 2006). When Laura Hurd Clarke (2000) interviewed women aged 61 to 92, she discovered that while older women say that their overall health is more important to them than physical attractiveness, they still exhibit an internalization of ageist beauty norms. As Sontag (quoted in Freedman 1986:200) says, “women are trained to want to continue looking like girls forever.”

This perspective also examines how ageism and sexism are reflected in the media. Though older adults are underrepresented in U.S. film, television programs, and advertisements in comparison with younger adults, older women are less likely to be featured than older men (Peterson and Ross 1997; Sanders 2002). When older women are portrayed, their characters represent negative stereotypes and are often shown as less successful compared with older men. Similar patterns were also documented in German media (Kessler, Rakoczy, and Staudinger 2004).

Mothers and Age

Interactionist Perspective

Interactionists reveal how our age-related roles are socially defined and expected. Age is tied to a system of matching people and roles (Hagestad and Uhlenberg 2005). What does it mean to be middle aged? Middle age is not just measured according to years, but is also associated with a set of role expectations. We share a definition of what it means to be middle aged, and there is an expectation that we need to assume a particular role once we are middle aged.

These role expectations stigmatize particular age groups. Stigma, coined by Erving Goffman ([1963] 1986), is defined as a discrediting attribute. Older adults are discredited in society, stereotyped as less capable, fragile, weak, and frail. Ageism or the stereotyping of (or discrimination against) older adults can damage the self-concepts of the elderly (Miller, Leyell, and Mazachek 2004) and represents a self-perpetuating cycle of fears that old and younger adults have toward aging in general, disability, death, competition for resources, and the perceived inferiority of particular individuals (Yang and Levkoff 2005). These images may increase social isolation, dependency, and elder abuse and may become a self-fulfilling prophecy for others (Thornton 2002). However, researchers have found that older adults from cultures with more positive attitudes toward aging than mainstream society may be able to avoid exposure to or internalization of the negative stereotypes of old age (Levy and Langer 1994).

Interactionists examine how the problems associated with aging have been defined and by whom. Society relies on trained experts such as gerontologists, physicians, nurses, and social workers to identify and respond to the problems of aging. Yet research indicates that this group of professionals is just as likely to be prejudiced against older people as other groups are. A. J. Levenson (1981) argues, “Medical students’ attitudes have reflected a prejudice against older persons surpassed only by their racial prejudice” (p. 61). He points to medical schools as part of the problem, putting little value on geriatrics as a specialty. Doctors often think that because aging cannot be stopped, illnesses associated with old age are not that important.

The medical industry has not ignored aging completely. Though controversial, the medical and cosmetic industries actively promote antiaging vitamins, hormones, surgeries, and pharmaceutical drugs, encouraging wellness to patients and clients while sending a message that they can “beat back old age” (Wilson 2007:BU1). Americans spend nearly $50 billion per year on antiaging vitamins, treatments, hormones, and pharmaceutical drugs (Wilson 2007). Are we responding to a genuine problem or one carefully manufactured by the medical and cosmetic industries?

A summary of all sociological perspectives is presented in Table 6.2.

Extreme Longevity

The Consequences of Age Inequality

Ageism

Ageism is defined by Robert Butler (1969) as the “systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old, just as racism and sexism accomplish this with skin color and gender” (p. 243). Todd Nelson (2005) described ageism as “prejudice against our feared self.” He suggests that age prejudice is one of the most socially condoned and institutionalized forms of prejudice. For example, a standard message in birthday greeting cards is how unfortunate one is to be a year older. In 2012, researcher Ye Luo and his colleagues reported that 63% of older adults reported at least one type of everyday discrimination (e.g., being treated with less courtesy, receiving poorer service, being threatened or harassed). Among older adults, Blacks; separated, widowed, or divorced individuals; and those with lower household assets have higher levels of discrimination than Whites, married individuals, and those with more assets (Luo et al. 2012).

Ageism marks a sharp distinction between “us” and “them.” William Bytheway (1995) explains it this way: “The issues of these pronouns creates a conceptual map on which groups of people are variously included and excluded. In particular, the old who are discriminated against occupy a different territory on these us/them maps from ‘us’” (p. 117).

Older adults tend to be marginalized, institutionalized, and stripped of their responsibility, dignity, and power (Nelson 2002). Dependency is one of the most negative attributes of being identified as “old” in our society (Calasanti and Slevin 2001). Stereotypes about the capacities, activities, and interests of older people reinforce the view that they are incapable of caring for themselves (Pampel 1998). Older adults are not generally disliked, but they are likely to be victims of paternalistic prejudice, which stereotypes them as likable but incompetent (Packer and Chasteen 2006). There is widespread acceptance of negative stereotypes about the elderly regarding their intellectual decline, conservatism, sexual decline, and lack of productivity (Levin and Levin 1980).

In a comparative study of young adults in the United States and Germany, German young adults tended to view aging more negatively than did Americans in the sample (McConatha et al. 2003). Germans were more likely to be pessimistic about the likelihood of finding contentment in old age and did not expect to feel good about life when they were older. The study attributed the differences in aging attitudes to Germany’s more prevalent negative stereotypes of older people, a response to the increasing costs of providing extension pension and health benefits to the elderly in Germany. On the other hand, in the United States, effective political advocacy groups, increasingly healthy and influential older adults, and educational aging programs may account for a reduction of ageism. The study also revealed that American and German women were more concerned about age-related physical changes than were men.

Age and Social Class

The most economically vulnerable in our society are very young or old. As discussed in Chapter 2, the rate of child poverty in the United States is one of the highest among Western industrialized countries. According to the U.S. Census, the poverty rate for children was 19.9%, or 14.7 million, in 2013 (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014). For a more extensive discussion on children and poverty, refer to Chapter 2, “Social Class and Poverty.”

Though most of us envision a retirement filled with leisure activities, travel, and good living, there is another possibility—that one’s retirement will be a time of serious economic hardship. In 2013, 4.2 million elderly (or 9.5%) were living in poverty in the United States (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014). Retirement represents a precipitous income drop for most elderly (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, and Smith 2012). The median income by age of householder was highest, at $67,141, for those aged 45 to 54 years for 2013 (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014). Median income begins to decline with the next age group, those aged 55 to 64, to $57,538. Finally, for those aged 65 or older, the reported median income was $35,611 (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014). For 2012, poor older adults relied on Social Security benefits more than higher-income older adults (refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for more information).

The economic recession depleted the incomes and savings of many older workers, leading some to admit that they are unable or afraid to retire. For example, 58-year-old Barbara Petrucci, a hospital employee from Atlanta, Georgia, set aside her dreams for an early retirement. After family savings were depleted by the declining stock market, Petrucci admits that retirement is “an elusive dream” (Rampell and Saltmarsh 2009).

As we have discussed in earlier chapters, the inequalities based on race/ethnicity and gender will also determine one’s economic status. Poverty rates among the elderly vary by race/ethnicity and gender. Older women have higher rates of poverty than older men do, 10.7% versus 6.6% (Issa and Zedlewski 2011). Women are especially susceptible to economic insecurity because of a number of factors. Women have longer life expectancies and are more likely to be widowed and live alone in old age. Because of gender differences in employment and salaries, women are likely to have less retirement income than men do. During 1999, women aged 65 or older received, on average, $8,000 annually as pension income, whereas men received $14,000 annually (He et al. 2005). Non-Hispanic White elderly have lower poverty rates than other reported racial groups. Blacks have the highest rate (19.3%), followed by Latinos (19.0%) and Whites (7.4%) (Rhee 2012).

In the European Union (EU25), about one in six elderly persons is at risk for living in poverty. In 14 of all EU25 countries, the elderly populations are at higher risk of being poor compared with working-age populations. The risk of poverty is highest in Cyprus, Ireland, and Slovenia. Rates are lowest among the elderly residing in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Lithuania, Latvia, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (Zaidi 2006).

Exploring social problems

Elderly Income

Social Security is funded through the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program. The earliest age that workers can receive benefits is 62, though benefits are about 25% lower than they would be at full retirement age. Though full retirement is often associated with 65 years of age, your actual retirement age will depend on your birth year. For those born in 1937 or earlier, retirement is 65 years. With each year from 1939, the retirement age is extended by monthly increments. For example, for someone born in 1941, his or her retirement age is 65 and 8 months. Currently the highest retirement age is 67 for those born in 1960 or later.

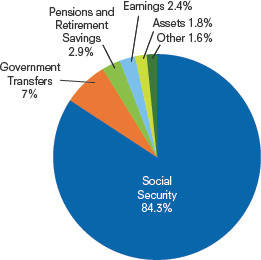

Figure 6.2 Income sources for the population aged 65 and over, lowest quintile, percentages reported, 2010

SOURCE: West et al. 2014.

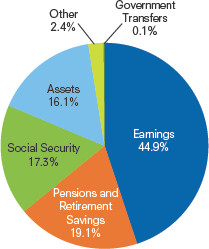

Figure 6.3 Income sources for the population aged 65 and over, highest quintile, percentages reported, 2010

SOURCE: West et al. 2014.

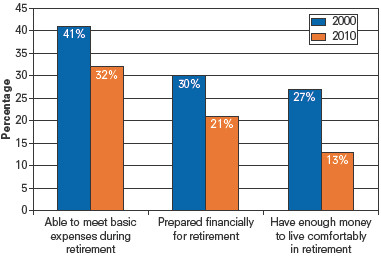

Figure 6.4 Workers aged 55 and over who are very confident about retirement finances, 2000 and 2010

SOURCE: West et al. 2014.

What Do You Think?

For those 65 years of age or older, Social Security payments accounted for the largest share of income, 36.7%, in 2010. The second largest share was from earnings at 30.2% (West et al. 2014). Figures 6.2 and 6.3 report income shares for the lowest and highest income quintiles.

Describe the difference in the income sources between these two quintiles.

In an annual survey, workers aged 55 and over were asked how confident they were about their retirement finances. The percentages of those who were very confident are reported in Figure 6.4. Results are presented for 2000 and 2010.

The data reported in Figure 6.4 combines responses from males and females. Hypothesize how gender might affect the level of confidence in retirement finances. Would men be more confident than women in their ability to meet their basic expenses during retirement? Why or why not?

Health and Medical Care

Much as they are more economically vulnerable, the young and the old experience the highest health risks among all age groups. We think of death as something that happens in one’s old age, yet the age group with the highest risk of mortality is newborns and infants within their first year of life. For 2009, the infant mortality rate was 6.39 deaths per 1,000 births (Murphy, Xu, and Kochanek 2012). The three leading causes of death among infants are congenital birth defects, low birth weight, and sudden infant death syndrome. Among the elderly, the majority of deaths are caused by heart disease, cancer, and stroke. The elderly also experience chronic conditions such as hypertension (high blood pressure) and heart disease that may contribute to fatal disorders. The elderly are more likely to experience chronic illnesses than younger age groups do, 46% versus 12% (Moody 2006).

Geriatrics is a medical specialty that focuses on diseases of the elderly; some are chronic, not all are life threatening, and others will eventually lead to death. The most prevalent chronic disease of the elderly is arthritis, inflammation of the joints and a leading cause of disability in the United States. Other geriatric diseases include osteoporosis (deterioration of bone tissue, prevalent among women), Parkinson’s disease (a degenerative neurological disorder), and dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (progressive loss of mental abilities and functions). For the last set of diseases, it should be noted that most older adults experience no mental impairment at all (Moody 2006). (A discussion of caregiving and elder abuse is presented in Chapter 7, “Families.”)

American elderly, who constitute 13% of our population, consume more than 35% of total health expenditures—more than four times what is spent on younger people (Moody 2006). The United States spends about 17.4% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care—the largest expenditure in this category among industrialized countries. During 2010, total health care spending reached $2.6 trillion, with an average of $8,086 spent per person (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2012).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Robinson 2007), older women face distinctly different challenges to maintain their health compared with older men. The financing and availability of health care is particularly important for older women. Because women make up a higher proportion of the older and frailer population, are less likely to have a spouse to assist them, and need more help with personal care and routine needs, older women use more health care and long-term care services than men do. Most older adults are covered by Medicare, but because older women rely on long-term care (not covered under Medicare), they make higher out-of-pocket payments or rely on Medicaid more often than older men do. Women rely on informal (unpaid) caregivers (adult children, family members, or friends), community-based services (senior centers and convenient transportation), and formal (paid) care services (home health care and nursing home care).

Ageism in the Workplace

In some businesses, age discrimination has an acronym, TFO, “too f___ing old” (Fisher 2004:46). Although much attention has been given to the marginalization of Black, Latino, or female workers, members of another labor force group—older workers—have experienced their own set of unique problems. In 2011, 22.1 million Americans aged 55 to 64 years were employed (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

Helen Dennis and Kathryn Thomas (2007) document how ageism continues to affect the hiring and promotion of older workers and workplace attitudes toward them. For example, most interview research indicates that older job interviewees whose qualifications are equal to those of younger candidates are less likely to be hired. Ageism restricts job opportunities for mature workers, as they are not offered the same promotion opportunities, training, or compensation as younger workers. Managers have mixed perceptions about older workers. Although older workers are valued for their work habits, skills, and performance, negative perceptions also exist. Older workers are perceived as inflexible, unwilling to adapt to technology, and more expensive (due to health insurance costs) when compared with younger workers.

In the United States, older workers are protected under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967. The act prohibits employers from discriminating based on age against people 40 to 64 years old. However, in 2008 the U.S. Supreme Court created a tougher burden of proof for plaintiffs in age bias cases. An employee would have to prove that age was the decisive factor (as opposed to a motivating factor) in an adverse employment decision. All EU countries have legislation banning age discrimination in employment, though in the United Kingdom 65 years old is considered the default mandatory retirement age.

In their study of older women’s employment agency placements in Auckland, New Zealand, Jocelyn Handy and Doreen Davy (2007) identified gendered ageism as a key barrier to permanent full-time employment for older women. Tracking women applicants in their mid-40s to early 60s, Handy and Davy documented how these women, despite their skills and qualifications, faced negative stereotypes concerning their appearance (looking their age) and a lack of “team fit.” One job seeker explained how a placement consultant told her that she was not suited for a position because she would remind the manager of his mother. Consultants valued physical presentation (beauty and youth) and also acknowledged how younger managers would perceive older workers as a threat. The older job seekers were often placed in low-paid, low-skilled temporary positions. The researchers concluded, “The gendered ageism affecting mature female clerical workers will not be solved simply by countering common stereotypes concerning older workers’ skills and necessitates greater attention to combating prejudices surrounding inter-age dynamics within the workplace” (pp. 95–96).

Employment Rate Doubles for Older Women

In Focus

The Political Influence of Young and Older Voters

The enactment of Social Security, Medicare, and other old-age–related policies has created a political constituency of older beneficiaries (Campbell 2003) and, along with it, the perception of political might. A form of ageism, the stereotype of “greedy” older voters willing to put their needs (Social Security and Medicare) ahead of the needs of other age groups, is accepted in many social, political, and media circles (Street and Crossman 2006).

Robert Binstock (2005, 2006) reveals some truths and myths about this perception of senior power. He explains that the senior political power model builds on the fact that older people represent a significant proportion of the electorate. Age is associated with voter registration and actual voting, which is also related to the length of residence in one’s home, along with one’s level of knowledge about political and social issues. Older persons are likely to have resided in their homes longer than have younger persons, and older people tend to be more knowledgeable about politics and news issues than younger people are. Studies indicate that older persons’ high level of interest in politics does not decline even as they reach advanced old age.

Older Americans have higher rates of voter registration than younger Americans. In addition, older men and women are more likely to contribute to a political campaign and contact their elected representatives regarding issues that matter to them.

Fitzgerald/CandidatePhotos/Newscom

In addition to their higher rates of voting participation, the elderly have higher rates of participation in other political areas. The elderly make campaign contributions at higher rates than do younger people—about 28% of all contributions to the 2000 presidential campaign came from older persons. Older voters are twice as likely to contact their state and federal representatives about issues that matter to them as younger voters are.

So, what impact does the voting participation by elderly Americans have on elections? One noticeable impact is on how it shapes candidate behavior—candidates actively court the senior vote. Recent presidential candidates have made key appearances at senior centers or promoted their proposals on Social Security and Medicare to selected senior audiences. But Binstock (2006) argues that the senior vote does not have a “distinctive impact on the outcome of elections” (p. 26). He explains that older Americans do not vote cohesively or as a bloc. Their votes are as diverse as those of any other age group, divided along partisan, class, gender, and racial lines. Age is just one characteristic among many that influence voting patterns.

For example, in the 2004 presidential election, the 65-or-older votes were distributed in approximately the same proportions—52% for President George W. Bush and 47% for Senator John Kerry—as were the votes of the general electorate—51% for Bush and 48% for Kerry. In the 2012 presidential election, older voters went against the popular vote—56% supported Governor Romney versus 44% who supported President Obama.

According to Scott Keeter, Juliana Horowitz, and Alec Tyson (2008), young voters have emerged as a key voting bloc for the Democratic Party. Since 2004, the majority of those under the age of 30 years have voted for a Democratic candidate in the general election. In 2008, 66% of voters 18 to 29 years of age voted for Barack Obama compared to 53% of all voters. This is the largest measured difference since exit polling began in 1972. Young voters are more ethnically and racially diverse and are less likely to be affiliated with a religious tradition than voters age 30 years or older. Additionally, voters 18 to 29 years of age expressed liberal views on the role of government (to solve problems) and were more likely to disapprove of the Iraq war than older voters. Though younger voters were less likely to contribute money to a campaign, the 18- to 29-year-old voter group had a rate of campaign event participation in battleground states higher than that of any other age group (Keeter et al. 2008). In 2012, President Obama received 60% of the youth vote in his campaign for reelection (Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement 2012).

Responding to Age Inequalities

Social Security and Medicare are social insurance programs designed to protect citizens against a specific set of risks. In the case of Social Security, the risk is that one might have insufficient resources at retirement and that one’s resources might not last one’s lifetime. How much health care will we need, and for how long are the risks addressed by Medicare? Both are proven, effective antipoverty programs, supporting elderly financial independence and enabling the elderly to live better and healthier lives (Feder and Friedland 2005). Since their inception, however, both programs have been the subjects of much debate.

Social Security

Social Security was first enacted with the Social Security Act of 1935. A year before, President Franklin D. Roosevelt convened an executive committee to examine economic insecurity, responding to the nation’s Great Depression. The committee’s recommendation was to create a program to address the long-range problem of economic security for the aged and poor, focusing not on providing social assistance (such as welfare assistance) but rather on a social insurance plan against an uncertain future (Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees 2007). We tend to think of Social Security only as the monthly payments one receives after retiring, but the program also supports unemployment insurance, aid to dependent children, and state grants to provide medical care.

Demographic shifts have led to new ways to think about aging and economic security throughout the globe. The current public pension system in the United States and in most of Europe is a pay-as-you-go system—current workers support current beneficiaries of the program (Curl and Hokenstad 2006), or today’s workers pay for today’s retirees (Moody 2006). Angela Curl and M. C. Hokenstad (2006) compared the U.S. Social Security system with public pension systems in Sweden and Canada. In Sweden, pensions are based on average life expectancy at the time of retirement. Workers can retire any time after 61 years of age, but the later they retire, the higher their payments will be. Because of the availability of part-time jobs and the flexible work environment, the program allows Swedes to draw a partial pension for partial retirement. The elderly can mix their employment income with their pension funds. The system is funded by an 18.5% payroll tax (the United States collects 12.4%). Unlike the U.S. system, Sweden’s system is partially privatized. Individuals can invest the money from their pension account, or the government invests on their behalf.

The Canadian public pension system is described as combining “income protection for older adults with policies that promote flexibility” (Curl and Hokenstad 2006:95). The Canadian system has three parts: the Old Age Security program, the Canada Pension Plan, and private pensions and savings. The minimum age of eligibility for early retirement benefits is 60 years. Canada collects a 9.9% payroll tax to support the program. As in the United States, both Canada and Sweden have residency requirements (persons must have lived for a certain number of years in the country) and a universal guaranteed monthly minimum benefit. The researchers praised both countries for promoting flexibility in retirement through gradual or partial retirement programs.

In the United States, policy analysts have long warned about the danger of having few workers paying for the benefits for a growing number of retirees. At the time the Social Security system was established, the elderly constituted 5% of the population (Moody 2006), and the average life expectancy was about 50 years of age (Curl and Hokenstad 2006). The proportion of the elderly in 2000 grew to 12%, and is projected to increase to 21% by 2050 (He et al. 2005). For 2014, the U.S. Social Security Administration paid benefits of $863 billion to nearly 59 million beneficiaries. On average, Social Security benefits represent about 38% of elderly income; 34% of workers have no retirement savings at all (Social Security Administration 2014a).

The Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees (2007), a nonpartisan panel responsible for reporting on the financial status of the Social Security Trust Funds, projects that tax revenues will fall below actual program costs in 2017. This is the year when the program will spend more than it receives through payroll deductions. The trustees predict that the trust funds will be exhausted in 2041 (OASDI Trustees 2007). Any worker born after 1975 will reach full retirement age after the trust fund is depleted. At the release of their 2007 report, the Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees warned, “The longer we wait to address these challenges, the more limited will be the options available, the greater will be the required adjustments, and the more severe the potential detrimental economic impact on our nation.”

A Secure Social Security

Attitudes About Aging Populations

Voices in the Community

Barbara Young

Encore.org is a nonprofit organization supporting older individuals as they pursue jobs in the nonprofit or public sector during the second half of their lives. The organization honors outstanding older employees with the annual Purpose Prize (Encore.org 2014). Barbara Young was a 2013 prize honoree (Encore.org 2013).

At the age of 63, Young joined the staff of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) as a national organizer. Since arriving to the United States from Barbados in 1993 with her five children, Young had worked as a bus conductor and then as a full-time nanny.

In 2001, Young enrolled in a nanny course for CPS and first-aid training, but the course also exposed Young to the history and labor abuses of domestic work. Young describes this as a pivotal moment, helping her decide to change the way nannies and other domestic workers define themselves and their work. “If the work you are doing is lifting up and enhancing the life of another person, then that work has value. This is the work that domestic workers do, day in and day out” (quoted in Encore.org 2013). Young worked first with the local Domestic Workers United before joining the national staff of NDWA.

In describing her work as a union organizer, Young says, “The goal was to let people know they matter, they are important, the job they were doing was important. And if I could get them to come and be a part of this organization [Domestic Workers United]—for me, it was building power, lifting up voices and building power” (quoted in Raab 2013). “And I want every domestic worker to see themselves as professionals, and to really know within themselves that they are a great big help and support in this economy” (quoted in Raab 2013).

Young was instrumental in the 2010 passage of New York State’s Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, which requires payment at minimum wage, higher overtime pay, and paid time off.

Medicare

The nation’s largest health insurance program, Medicare, covers about 54 million elderly or disabled Americans. Medicare has two parts: Part A (hospital insurance) helps pay for care received as an inpatient in critical access hospitals or skilled nursing facilities, as well as some home health care; Part B (physician and outpatient coverage) pays for medically necessary services and supplies that are not covered under Part A. Each part is financed under a different structure. Part A is offered as an automatic premium because most recipients (or their spouses) paid Medicare taxes while they were working. Part A is financed through a payroll tax paid equally by employers and workers. Three fourths of the financing for Medicare Part B is received from general tax revenues, and the remaining quarter is financed directly through paid premiums, $104.90 (for those with individual incomes of $85,000 or less) or $146.90 or higher (for those with individual incomes higher than $85,000) in 2012.

Since the program’s inception, some have been concerned that Medicare spending, especially for Part A, will outpace its revenue sources (Moon 1999). Medicare has been referred to as a pay-as-you-go system; every payroll tax dollar that is contributed into the fund is immediately spent by those currently enrolled (Goodman 1998). Since 2008, the trust has been spending more on benefits than it has been receiving through payroll taxes. In a 2014 report, the trustees warned that the Medicare fund would be depleted by 2030 (Social Security Administration 2014b).

Political rhetoric continues to swirl around how to preserve the system while trying to expand its services to an ever-increasing population of elderly. In 2003, the U.S. Congress passed the Medicare reform law, which included a prescription drug benefit for the first time in the program’s history. The bill provides for a prescription drug benefit for older and disabled Americans, offered and managed by private insurers and health plans under contract with the federal government. Critics attacked the plan for its coverage gap, arguing that the bill failed to provide seniors with substantial relief for the cost of prescription drugs. Seniors with low incomes will qualify for extra assistance under the bill. The cost of the bill is estimated at more than $900 billion over 10 years. Analysts predict that the reform bill will have little effect on slowing down the increasing costs of prescription drugs and medical services for the elderly.

The traditional nursing home care model is no longer considered financially viable or medically justified. There has been an increase in the utilization of older adult managed care at home, at day care centers, and in visits to specialists (Berger 2012). Similar programs have been adopted in Canada, like the Comprehensive Home Option for Integrated Care of the Elderly (CHOICE). CHOICE has been credited with keeping elderly men and women healthier longer and out of long-term care homes because medical workers are able to more closely monitor their patients’ health (Howell 2011). Medicare and other medical service organizations have encouraged the use of older volunteers as health coaches, advocates, and aides to help individuals and families navigate through the health care system. For example, the Rose Community Foundation in Denver trains older adults as community health workers (Pope 2012).

For more on increasing medical costs and alternative models of care, refer to Chapter 10, “Health and Medicine.”

Sociology at Work

Social Work

Kacie Blanchard – Class of 2006

Undergraduate Major: Sociology

Undergraduate Minor: Communications

In a survey of BA Sociology graduates, the American Sociological Association (Spalter-Roth and Van Vooren 2008) reported that that largest category of alums working full time, 27%, were employed in social service and counseling occupations. Social work is the primary occupational field in the social services. Preparing for a career as a social worker can be ambiguous, as positions vary widely, from caseworker to mental health assistant to clinical social worker. To enter the field of social work, a bachelor’s degree is the most common requirement; however, a clinical position may require a master’s degree and up to two years of experience.

After completing her Sociology BA, Kacie Blanchard earned a Master of Social Work degree in a two-year accredited program. She credits her internship experience with helping her identify her career path. “I was unsure what direction my degree would take me until I had the experience of working with child protective services. Once I had this opportunity, I knew I wanted to attend graduate school and become a social worker. I then saw social work as putting sociology into action.”

In her current position as a medical social worker, Kacie works with clients to assess their need for placement and home safety following changes in their health and medical needs. She also conducts mental health assessments, identifying psychosocial needs to assist patients upon their return from the hospital to maintain their health and safety. Kacie also works as a crisis intervention therapist on a mobile outreach crisis team. In Kacie’s occupation, interpersonal skills are important because of the specific nature of the work—helping clients from diverse populations during some of the most difficult times in their lives.

When asked how she applies sociology in her social work practice, Kacie replied,

Knowledge of social systems and the entire picture of each individual with the understanding of psycho-social history assists me each day to direct my interventions and predict outcomes. Sociology is the foundation of my social work practice. Sociology ignited my passion and is the root of my daily interactions as a social worker. I continue to engage my sociological imagination by remembering this foundation and applying it to my career as a social worker.

For current Sociology majors, Kacie recommends

focusing on an aspect of sociology that is most interesting to them, whether that be criminal studies, child welfare, family systems, and use that as a starting point for a career. For me, my introduction into child welfare started my career path that continues to grow. Keep your connections with sociology classmates and professors for networking and support.

Chapter Review

- 6.1 Explain how age is both a biological and a social classification

Our age is measured biologically, by how old we are, and we have socially and culturally defined expectations about the meaning of age, our understanding of it, and our responses to it. Age distinguishes acceptable behavior for different social groups.

- 6.2 Identify the causes of population aging

Demographers study the size, composition, and distribution of human populations. Population aging is caused by a decline in the birthrate. Aging can also occur because of an improvement in life expectancy as a result of medical and technological advances. Finally, the process of population aging can be influenced by characteristics of birth cohorts.

- 6.3 Describe how the sociological perspectives address age, aging, and inequality

Functionalists rely on disengagement theory to explain aging as a natural process of withdrawal from active participation in social life; people enter and exit a set of roles throughout their lives. Conflict theorists offer the modernization theory of aging to explain how the role and status of the elderly decline with industrialization. The power, wealth, and prestige of the elderly are linked with their labor contribution or their relationship to the means of production. According to the feminist perspective, the standards of our culture create more problems for women than for men as they transition into their middle and later years. Interactionists reveal how our age-related roles are socially defined and expected.

- 6.4 Explain how age serves as a basis for prejudice or discrimination

Ageism is the systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against people, primarily the elderly. Age distinguishes acceptable behavior for different social groups.

- 6.5 Examine the characteristics of young and older voters

Though age is related to voter registration, actual voting, and political participation, older Americans do not vote cohesively or as a bloc. Their votes are as diverse as those of any other age group. Younger voters were a key voting bloc in recent presidential elections. Young voters are more ethnically and racially diverse and less likely to be religiously affiliated.

Key Terms

- ageism, 155

- boomerangers, 152

- demography, 148

- disengagement theory, 152

- double standard of aging, 154

- gerontology, 148

- life course perspective, 148

- modernization theory of aging, 153

- population aging, 148

- stigma, 155

Study Questions

- How do social norms—formal or informal—shape our definition of age?

- Identify the societal consequences of population aging.

- Disengagement theory defines aging as a natural process of withdrawal from active social participation. Do you think this disengagement is a natural process or brought on by social factors? Explain.

- From an interactionist’s perspective, how can we improve the status of the elderly?

- In what ways are elderly women disadvantaged in society in comparison with elderly men?

- Compare and contrast the U.S. Social Security system with the pension systems in Sweden and Canada.

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.