Chapter 5 Sexual Orientation

Learning Objectives

- 5.1 Define sexual orientation

- 5.2 Describe how each sociological perspective addresses sexual orientation and inequality

- 5.3 Explain the expansion of the rights and recognition of same-sex couples in the United States

- 5.4 Examine whether children raised by gay or lesbian parents have different life outcomes compared to children raised by heterosexual parents

In a 2009 announcement that led to worldwide condemnation, lawmakers in Uganda considered adopting an antihomosexuality law, proposing the death penalty for certain homosexual acts (e.g., with a minor, if the perpetrator was HIV positive, or for serial offenders) (Gettleman 2010). David Kato was one of the leading voices against the legislation. Despite threats of violence and harm, Kato, an openly gay man, maintained, “If we keep on hiding, they will say we are not here.” Kato cofounded the advocacy group Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG). In 2011, Kato was murdered several weeks after winning a court decision over a Ugandan tabloid that called for the killing of homosexuals. Uganda’s antihomosexuality bill was passed in 2013, substituting the death penalty clause for life imprisonment. SMUG reported an increase in the cases of intimidation and violence against Uganda’s homosexual population after the passage of the bill. In 2014, Uganda’s constitutional court overturned the law. The gay and lesbian community celebrated the ruling with its first gay pride rally.

One’s sexual orientation serves as a basis of inequality. Sexual orientation is defined as the classification of individuals according to their preference for emotional-sexual relationships and lifestyle with persons of the same sex (homosexuality) or persons of the opposite sex (heterosexuality). Bisexuality refers to emotional and sexual attractions to persons of either sex. The term transgender does not refer to a specific sexual orientation; rather, it refers to individuals whose gender identity is different from the one assigned to them at birth. The term LGBT is often used to refer to lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender individuals as a group.

There is no definitive study on the number of individuals who identify as homosexual or bisexual. The study that is most often cited was conducted in 1994 by Robert Michael and his colleagues. Based on a random survey of 3,432 U.S. adults ages 18 to 59 years, Michael et al. found that 2.8% of men and 1.4% of women thought of themselves as homosexual or bisexual. About 5% of surveyed men and 4% of women said they had had sex with someone of the same gender after they turned 18. About 6% of men and 4% of women reported that they were sexually attracted to someone of the same gender.

When the Gallup Organization conducted a national survey of more than 120,000 Americans in 2012, 3.4% of respondents identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (Gates and Newport 2012). In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that less than 3% of the U.S. population identify as gay. Based on the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey, 1.6% of adults self-identify as gay or lesbian and 0.7% as bisexual (Ward et al. 2014).

Gay rights have progressed in the United States and globally. In 1996, South Africa became the first country to establish a constitutional ban against discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 2000, Vermont was the first U.S. state to recognize civil unions between same-sex partners; in 2004, Massachusetts was the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. Though national polls indicate increased support of gay and lesbian individuals, as a group they are still not immune to the experience of social problems. Based on their sexual orientation, LGBT individuals continue to experience prejudice, discrimination, harassment, and violence. Their struggle for equal protection and opportunities continues.

Sociological Perspectives on Sexual Orientation and Inequality

Our understanding of sexual orientation is based upon research from biology, psychology, and sociology. Each examines the causes and consequences of sexual orientation from its unique and sometimes controversial point of view.

Researchers exploring the biological basis of sexual orientation have considered two theoretical approaches. The first is neurohormonal theory, arguing that homosexuality is caused by atypical sex hormone levels in utero. Human studies have suggested that specific centers in the brain are related to sexual orientation and sexual behavior. The second approach is based upon behavioral genetics, identifying the source and magnitude of genetic influences on sexual orientation. This line of research was first motivated by the idea that gay men are genetically female, a hypothesis that was eventually discredited.

Confirmation of the genetic link to sexual orientation has been found through comparative studies of identical twins (twins who have nearly identical genetic makeup) and fraternal twins (twins who share some similar genetic makeup). Bailey and Pillard (1991) and Bailey and Bell (1993) found it more likely that identical twins will both be gay (if one is gay) than is the case for fraternal twins. In their assessment of biological research on sexual orientation, Brian Mustanski, Meredith Chivers, and Michael Bailey (2002) concluded that sexual orientation is influenced by biological factors to some degree. They say that the questions that remain to be answered are how and when these biological factors act and to what degree these factors influence sexual orientation in women and men.

Early psychological studies treated homosexuality as a pathology, as a mental illness. This perspective was not universal among psychologists. Havelock Ellis argued that homosexuality was inborn, and therefore could not be considered a disease (Robinson 1976). Sigmund Freud believed that all humans were innately bisexual and that homosexuality and heterosexuality were the result of social and personal experiences. Both agreed that homosexuality was not an illness.

However, homosexuality was explicitly defined as a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1973; a diagnosis for ego-dystonic homosexuality was introduced in 1980 but removed entirely in 1986. The World Health Organization removed a similar classification from its International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems in 1992. The declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness was in response to empirical research but also to more favorable cultural and social norms pertaining to homosexuality.

Shifting away from homosexuality as an illness, psychologists currently examine the impact of a homosexual identity. Rates of mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidality) are higher among homosexual men and women due in part to the social discrimination and cultural stigmatization they experience. Researchers in this field also examine the causes of attitudes toward homosexuality, particularly homophobia. A socially determined prejudice, homophobia is an irrational fear or intolerance of homosexuals (Lehne 1995). Homophobia is particularly directed at gay men.

In contrast to these biological and psychological perspectives, the sociological perspective examines the social and structural factors that affect sexual orientation.

Functionalist Perspective

Theorists in this perspective examine how society maintains our social order. Émile Durkheim argued that our social order depends on how well society can control individual behavior. Our most basic human behavior—our sexuality—is controlled by society’s norms and values. Functionalists identify how society upholds heterosexuality and a marital union between a man and a woman as ideal normative behavior. This is also referred to as institutionalized heterosexuality, the set of ideas, institutions, and relationships that define the heterosexual family as the societal norm (Lind 2004).

Our legal, political, and social structures work in harmony to support these ideals (the conflict perspective of this is presented in the next section). Section 3 of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) denied federal recognition of same-sex unions, defining marriage as a legal union only between a man and a woman. This legislation served as a declaration about how the heterosexual family is valued and how all other family forms are not. Society grants legitimate kinship and familial obligations only through the heterosexual family. Consequently, society defines all other forms of sexuality and families that do not fit this ideal image as problematic. These forms are considered deviant or unnatural because they do not fit society’s ideal.

Nonetheless, during the past decades, the gay rights movement has effectively influenced family rights, employment, and discrimination policies throughout the world. The movement has been successful largely because of its ability to affect institutional (macro) level changes—the focus of the functionalist perspective.

Gay Lifestyle Myth

Conflict and Feminist Perspectives

Gore Vidal (1988) observed the following:

In order for a ruling class to rule, there must be arbitrary prohibitions. Of all prohibitions, sexual taboo is the most useful because sex involves everyone. . . . we have allowed our governors to divide the population into two teams. One team is good, godly, straight; the other is evil, sick and vicious.

Vidal’s statement addresses the focus of both these perspectives, how conflict in our society is based on sexual orientation, with heterosexuals having been given the advantage. This reaffirmation of heterosexuality as the moral standard is the basis of the culture wars, the struggle over creating and regulating codes of personal, social, and sexual behavior for every American. Contemporary culture wars have also concerned issues of race, ethnicity, and immigration, but the majority of culture wars revolve around issues of sexuality and gender (Bronski 1998).

Sociologists recognize that heterosexuals are granted a privileged place in our society. Heterosexism assumes that heterosexuality is the norm, encouraging discrimination in favor of heterosexuals and against homosexuals. Heterosexual privilege is defined as the set of privileges or advantages granted to some people because of their heterosexuality.

From a conflict perspective, Amy Lind (2004) identifies how DOMA helped institutionalize heterosexism because it blocked future proactive and protective legislation for gays and lesbians. She focuses specifically on heterosexual biases in social welfare policy, identifying its impact in three ways: through policies that explicitly target LGBT individuals as abnormal or deviant, through federal definitions that assume that all families are heterosexual, and through policies that overlook LGBT poverty and social needs because of stereotypes about affluence among LGBT families.

Evidence of the first type of heterosexual bias can be found in federal legislation such as DOMA and policy initiatives such as the healthy marriage promotion and fatherhood programs promoted by President George W. Bush. Current legislation funds abstinence only through marriage education programs in schools. Lind (2004) explains that gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents have no access to sexual education that pertains to their sexual experience. In an effort to preserve the traditional heterosexual family, these programs deny LGBT people their rights and needs.

The second type of heterosexual bias concerns how the U.S. Census defines the family and household. Lind (2004:28) refers to the 2003 definitions used by the U.S. Census. Family is defined as “a group of two or more (one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together.” A household “consists of all people who occupy a housing unit” and is distinguished by family versus nonfamily households. Family households are defined as “a household maintained by a householder who is in a family (as defined above) and includes any unrelated people who may be residing there,” whereas a nonfamily household is “a householder living alone or where the householder shares a home exclusively with people to whom he/she is not related.” Lind argues that these definitions privilege marital unions over domestic partnerships and the status of heterosexual families over other types of families. Beginning with the 2010 Census, same-sex couples can select between two options to indicate their relationship status: “husband and wife” and “unmarried partners.”

Families like Oliver du Wulf (L) and Steven Boulliane’s (R) help expand our definition of a “family.” Public polls reveal increasing support for same-sex marriage. As of 2015, more than 50% of surveyed Americans were in favor of the legal recognition of same-sex marriage.

SHIH WEBER/SIPA/Newscom

Finally, the third type of heterosexual bias is based on stereotypes of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals and families as affluent, despite evidence that LGB families are as economically diverse and stratified as heterosexual families. Lesbians, gays, and bisexuals remain invisible in poverty studies or policies because they are assumed to be childless, have fewer family responsibilities, and thus have higher overall incomes than heterosexual households. The Movement Advancement Project, the Family Equality Council, and the Center for American Progress (2012) report that contrary to the stereotype, children raised by same-sex couples are twice as likely to live in poverty than children raised by heterosexual couples. With the exception of HIV/AIDS, it is assumed that LGB individuals do not need any economic, social, or health-related services.

From a feminist perspective, the question about gay marriage rights is bound to the ongoing critique of marriage as an institution (Bevacqua 2004). Scholars have argued that lesbian and gay marriages will positively disrupt the gendered definitions of marriage and the assumption that marriage is a prescribed hierarchy (Hunter 1995). However, just as feminists have criticized traditional marriage as an oppressive and dominating institution against women, feminists have also supported sexual freedom. Thus, supporting gay marriages would mean supporting the very institution that perpetuates women’s inequality.

Ann Ferguson (2007) explains that there are two main sides of the feminist argument: radical feminists who reject marriage outright on the basis of marriage as an oppressive institution versus liberal reform feminists who support the choice to marry on the understanding that men and women (or same-sex couples) can conduct their marriages in nontraditional ways. While she does not oppose long-term relationships or partnerships, radical feminist Claudia Card (1996) objects to the origins and consequences of marriage. Marriage, according to Card, has its roots not in love but in property and power, which may include the power of men over women and children. Ultimately the state, an authority external to the relationship, legitimates marriage and its subsequent benefits (i.e., federal, state, and legal benefits extended to heterosexual couples). Card states that since the institution of marriage is flawed in its origin and practice, gays and lesbians should focus their efforts on other institutional changes, such as a national health care policy that provides everyone with health coverage and access. On the other hand, Ferguson (2007) supports the liberal reform side, arguing, “We should not simply reject marriage and hope it withers away, but instead should attempt to reform it as a better way to achieve these feminist goals [equality, freedom, and care]” (p. 52). On the topic of gay marriage, however, she concludes that some gay persons should not marry, not because it is a risky institution for women, but because the right to form one’s family should not be tied to one’s marital status. “We should defend gay marriage as the formal right to access a basic citizen right” (Ferguson 2007:54).

Interactionist Perspective

In our society, no one gets “outed” for being straight. There is little controversy in identifying someone as heterosexual. Socially, culturally, and legally, the heterosexual lifestyle is promoted and praised. Although homosexuality has existed in most societies, it has usually been attached to a negative label—abnormal, sinful, or inappropriate. A homosexual identity also becomes a master status, an identity that determines how others view individuals and how individuals view themselves.

Interactionists examine how sexual orientation is constructed within a social context. We tend to think of heterosexuality as unchanging and universal; however, Jonathan Katz (2003) explains how the term is a social invention that “designates a word and concept, a norm and role, an individual and group identity, a behavior and a feeling, and a peculiar sexual-political institution particular to the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries” (p. 145). Though heterosexuality existed before it was actually named in the early nineteenth century, “The titling and envisioning of heterosexuality did play an important role in consolidating the construction of the heterosexual’s social existence” (Katz 2003:145). He argues that acknowledging heterosexuality as a social invention—time bound and culturally specific—challenges the power of the heterosexual ideal.

Interactionists also examine the process of how individuals identify themselves as homosexual, what scholars describe as part of the development of a gay identity. Coming out (being gay and disclosing it to others) has come to symbolize the pursuit of individual rights and self-identification (Chou 2001). Coming out implies not just the disclosure of a gay identity but also the individual’s positive attitude toward and commitment to that identity (Dubé 2000). The disclosure of a gay identity merges a private sexual identity with a public social identity (Cass 1979). To come out successfully, a gay individual needs social and institutional support, in the form of support from family and friends, legal protection from discrimination and violence, cultural acceptance, financial equality, and access to health services (D’Augelli 1998).

The process of coming out to family members is particularly stressful for LGB youth. Fear of parental reactions has been identified as a major reason that LGB youth do not come out to their families (D’Augelli, Hershberger, and Pilkington 1998). Following disclosure, youth report verbal abuse and even physical attacks by family members. Youth who lived with their families and disclosed their sexual orientation were victimized by their families more often than were youth who had not disclosed their orientation (D’Augelli et al. 1998).

To avoid negative response from others, young lesbians and gay men hide their sexual orientation from family and friends (Rivers and Carragher 2003). Gay and lesbian youth may use one or more of the following concealment strategies: inhibiting behaviors and interests associated with homosexuality, limiting exposure to the opposite sex, avoiding exposure to information about homosexuality, assuming antigay positions, establishing heterosexual relationships, and avoiding homoerotic feelings through substance abuse (Radkowsky and Siegel 1997). Research is inconclusive about how effective such concealment strategies are in reducing anxiety among lesbian and gay youth.

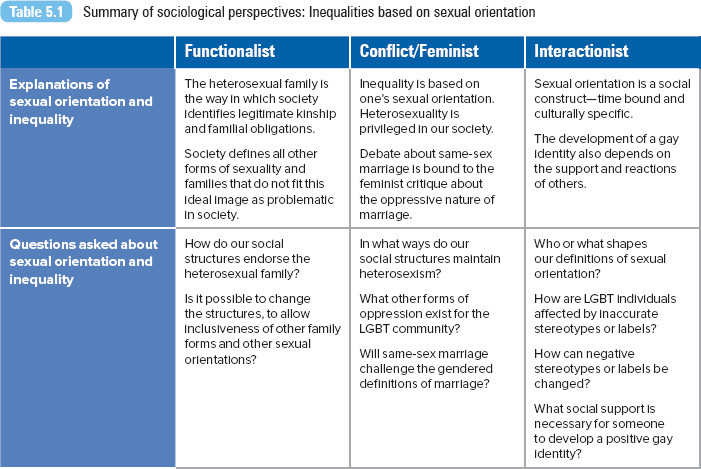

A summary of sociological theories regarding sexual orientation and inequality is presented in Table 5.1.

Sexual Orientation and Inequality

U.S. Legislation on Homosexuality

Bisexual or homosexual men, women, and their families are subject to social inequalities through practices of discrimination and prejudice, many of them surprisingly institutionalized in formal law.

For example, sodomy laws criminalize oral and anal sex between two adults. Although the laws may apply to homosexuals and heterosexuals, sodomy laws are more vigorously applied against same-sex partners. Twelve U.S. states still had state sodomy laws in 2014 (in 1960, sodomy was outlawed in every state).

In 1998, John Lawrence and Tyron Garner were fined $200 and spent a night in jail for violating a Texas statute that prohibited “deviate sexual intercourse” between two people of the same sex. The Texas statute did not apply to heterosexual couples. Their case was heard before the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2003. Attorneys for Lawrence and Garner argued that the Texas law was an invasion of their privacy and violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because it unfairly targeted same-sex couples. Attorneys for the state argued that Texas had the right to set moral standards for its residents. In June 2003, the court voted 6 to 3 to overrule the Texas law and all other remaining sodomy laws. Writing for the decision, Justice Anthony Kennedy said, “The state cannot demean their [homosexuals’] existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime” (Greenhouse 2003:A17). According to Kevin Cathcart, executive director of Lambda Legal (2003), “this ruling starts an entirely new chapter in our fight for equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people.”

In 2009, the U.S. Congress passed legislation to grant gay individuals protection under hate-crime laws. The legislation was in response to the brutal deaths of James Byrd Jr., an African American who was dragged to death in Texas, and Matthew Shepard, a gay college student who was beaten and left to die in Wyoming. The federal hate-crime law, enacted in 1968, had been limited to crimes based on race, color, religion, and national origin. Though supported by civil rights and law enforcement groups, some conservative and religious groups opposed the legislation, saying that the bill would create special classes of federally protected crime victims. The 2009 legislation also extended protections for disabled individuals. At the signing of the bill, President Barack Obama promised that people would be protected from violence based on “what they look like, who they love, how they pray or who they are” (Feller 2009).

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the first-of-its-kind California law that bans psychological counseling aimed at changing the sexual orientations of gay and lesbian minors. Conversion or reparative therapy refers to counseling and psychotherapy to eliminate sexual desires for members of one’s own sex (American Psychological Association 2008). Under the 2012 California law, reparative therapy is prohibited for patients under the age of 18. Governor Jerry Brown and gay rights advocates supported the law, arguing that these therapies have no medical or scientific bases. The American Psychiatric Association determined that reparative therapy poses a risk of depression, anxiety, self-hatred, and self-destructive behavior for patients (Levs 2012). New Jersey was the second state to ban sexual orientation conversion therapy. As of 2014, bans were also being considered in Massachusetts and New York.

Matthew Shepard’s Murder

The Rights and Recognition of Same-Sex Couples

Before 2013, DOMA permitted states to ban all recognition of same-sex marriages. According to the law, the federal government would not accept marriage licenses granted to same-sex couples, regardless of whether a state provides equal license privileges to all types of partnerships. DOMA denied these couples the same federal benefits that are available to or required for married opposite-sex couples. Gay and lesbian families were denied common legal protections that nongay families take for granted, such as adoption, custody, guardianship, social security, and inheritance.

The legal recognition of same-sex couples began incrementally at the federal level. In June 2002, President George W. Bush signed into law the Mychal Judge Act, which allows federal death benefits to be paid to the same-sex partners of firefighters and police officers who die in the line of duty (Bumiller 2002). In 2006, the federal Pension Protection Act became law, containing two key provisions that extend financial protections to same-sex couples and Americans who leave their retirement savings to non-spouse beneficiaries. Under the law, an individual’s retirement plan benefit can be transferred to a domestic partner or other non-spouse beneficiary. The second provision allows gay couples and others with non-spouse beneficiaries to draw on their retirement funds in the case of a medical or financial emergency. And in 2010, President Barack Obama instructed the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to draft rules requiring hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid payments (which includes most of the nation’s medical facilities) to grant all patients the right to say who has visitation rights and who can help make medical decisions. These rules would allow full recognition of advanced health directives among gay and lesbian couples.

In 2011, President Obama directed the U.S. Justice Department to stop defending DOMA in court after concluding that the law was unconstitutional (Savage and Stolberg 2011). In 2012, President Obama expressed his support for marriage of same-sex couples. Governor Mitt Romney, the 2012 Republican presidential nominee, continued to advocate marriage as a relationship between one man and one woman. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that DOMA was unconstitutional.

For more on same-sex marriage legislation, refer to the discussion on family legislation in the last section of this chapter.

Same-Sex Marriage and the Supreme Court

Employment

The need to “manage a disreputable sexual identity at the workplace” has been called the most persistent problem facing lesbians and gay men (Schneider 1986:464). Between 16% and 46% of gays, lesbians, and bisexuals have experienced workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation (Katz and LaVan 2004). Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination because of sex. Sex has been interpreted to mean gender, which means that protection for homosexuals based on sexual orientation is not covered.

M. V. Badgett and Mary King (1997) note that, unlike discrimination based on easily observable characteristics such as skin color or gender, discrimination against gays and lesbians must be based on knowledge or suspicion of someone’s sexual orientation. Lesbians and gay men who reveal their sexual orientation risk loss of income and lower chances at career advancement. A review of existing studies on workplace discrimination reveals that somewhere between one quarter and two thirds of LGB people report losing their jobs or missing promotions because of their sexual orientation.

Protections against public and private workplace discrimination because of one’s sexual orientation exist in 21 states, the District of Columbia, and several hundred U.S. cities and counties. Eighty-eight percent of all Fortune 500 companies have antidiscrimination policies that include sexual orientation, and 57% have policies that include gender identity (Human Rights Campaign 2013). Currently there is no federal law that protects LGBT individuals from employment discrimination. In 2009, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) was introduced in the U.S. Congress. If passed, the act would provide basic protections against workplace discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Professional competitive sports have been referred to as the “last closet.” “Sports associate boys and men with masculine dominance by constructing their identities and sculpting their bodies to align with hegemonic perspectives of masculinist embodiment and expression” (Anderson 2011). Since 2012, several professional and collegiate players have revealed their sexual orientation: Jason Collins (NBA), Brittney Griner (WNBA), and Michael Sam (NFL). Nearly all professional sport leagues ban discrimination based on sexual orientation, along with race, religion, and ethnicity. Yet, Cyd Zeigler, editor of Outsports, an online publication covering LGBT men and women in sports, says,

I think homophobia for decades has been more entrenched in sports than it has in most other areas in our culture . . . It starts when these kids are young. And they’re five years old and 10 years old and playing sports and the coach calls them a faggot and tells them not to be a sissy and this idea that being a faggot is less than being a man. (Quoted in Chibbaro 2013)

Upon his retirement from the NBA, Collins (2014) said,

When we get to the point where a gay pro athlete is no longer forced to live in fear that he’ll be shunned by teammates or outed by tabloids, when we get to the point where he plays while his significant other waits in the family room, when we get to the point where he’s not compelled to hide his true self and is able to live an authentic life, then coming out won’t be such a big deal. But we’re not there yet.

Employment Discrimination

Responding to Sexual Orientation Inequalities

In this section, we’ll review the progress on marriage equality and military service. Despite the progress in these two areas, it is important to note how LGBT individuals still lack basic legal protections. According to the Human Rights Campaign (2014d), “the patchwork nature of current LGBT civil rights protections protects millions of people, but leaves millions more subject to uncertainty and potential discrimination that impacts their safety, their family and their very way of life.” As of December 2014, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act had yet to be passed in the U.S. Congress. There are no explicit protections prohibiting the denial of credit (including housing loans) based on sexual orientation or gender identity, no consistent federal protections for students based on sexual orientation or gender identity, and no federal protections that prohibit discrimination against LGBT people in public spaces, such as hotels or restaurants (Human Rights Campaign 2014a).

Family Legislation

In May 2004, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to legalize same-sex marriage. As of May 2015 in addition to Massachusetts, 36 other states—Alaska, Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming—had legalized gay marriage. (Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature to understand the increasing support for marriage equality.)

In 2004, Del Martin (left) and Phyllis Lyon were the first legally married, same-sex couple in California, after San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom (center) allowed marriage licenses to be issued to same-sex couples. Within a few months, their marriage license, along with several thousand other licenses, was declared invalid. They were married again in 2008, after the California Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage was legal.

© Marcio Sanchez/Pool/epa/Corbis

Data on same-sex marriages were first released by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2009. Previously the bureau argued that DOMA prevented the federal government from recognizing these marriages, and as a result, it would not include them in any census reporting. Same-sex marriages, unions, and partnerships were counted for the first time in the 2010 Census. The 2010 U.S. Census estimated that there were 131,729 same-sex married-couple households and 514,735 same-sex unmarried-partner households (O’Connell and Feliz 2011). The cities with the highest rates of same-sex couples were Provincetown, Massachusetts; Wilton Manors, Florida; and Palm Springs, California (Tavernise 2011). It is estimated that 2 million children are being raised in LGBT families (Movement Advancement Project et al. 2012).

Denmark was the first European country to recognize same-sex unions, in 1989. In 2006, South Africa passed its Civil Union Act, extending the legal rights of marriage to same-sex unions. The act is based on South Africa’s constitution, which was the first in the world to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. Marriages legal in these and other countries may not be recognized by other countries. (Refer to Table 5.2 for a complete list of same-sex marriage and partnership recognition throughout the world.)

The laws governing the rights and responsibilities of gay parents still vary from state to state. Every state allows an individual to petition to adopt a child. (Until 2010, Florida was the only state that explicitly forbade adoption by unmarried gay, lesbian, or bisexual individuals. First enacted in 1977, the Florida law was ruled unconstitutional by a state court of appeals.) At the end of 2014, 23 states and the District of Columbia allowed same-sex couples to petition jointly to adopt; 8 states restricted or banned these adoptions (Human Rights Campaign 2014b). Second-parent or stepparent adoptions options are available in 24 states and the District of Columbia (Human Rights Campaign 2014c).

NOTE: Countries that offer most or all spousal rights to same-sex and couples, but stop short of marriage, include the following: Germany, and Italy. Countries that offer some spousal rights to same-sex couples include the following: Croatia, Hungary, Israel, and Switzerland.

Academic research has consistently indicated that gay parents and their children do not differ significantly from heterosexual parents and their children (Schumm 2006). There is little or no evidence that the children of gay or lesbian parents are disadvantaged in any important way in comparison with children of heterosexual parents (Patterson and Redding 1996); children raised by gay or lesbian parents have no increased gender-identity problems and are just as socially well adjusted as children raised by heterosexual couples (Schumm 2006; Redding 2008).

For their classic 2001 research, Judith Stacey and Timothy Biblarz examined the findings of 21 studies that explored how parental sexual orientation affects children. Based on the evidence, they concluded that there are no significant differences between children of lesbian mothers and children of heterosexual mothers on measures of social and psychological adjustment, such as self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. Across studies, there was no relationship between parental sexual orientation and measures of children’s cognitive ability. Also, levels of closeness and the quality of parent–child relationships did not vary significantly by parental sexual orientation. Stacey and Biblarz (2001) concluded,

We propose that homophobia and discrimination are the chief reasons why parental sexual orientation matters at all. Because lesbigay parents do not enjoy the same rights, respect and recognition as heterosexual parents, their children contend with the burdens of vicarious sexual stigma. (p. 177)

In their 2012 report, the Movement Advancement Project et al. documented how difficult it was for same-sex couples to establish legal ties to each other and to their children. Due to outdated state family laws that do not recognize or support contemporary family structures, children living in LGBT families are more likely to have legal ties to only one parent than children living with heterosexual married parents. As a result, LGBT families bear a variety of financial, legal, and emotional costs. For example, only one parent may have the authority to make routine or emergency decisions for the child, or the child may not be eligible to receive medical coverage through the employer of the nonbiological or nonlegal parent. If the biological or legal parent were to die, the child would be placed with a distant relative or in foster care instead of being placed with the nonlegal parent. The report concludes with recommendations for legislative solutions focusing on the best interests of the children, establishing legal ties to both parents, and eliminating the potential for bias and discrimination against LGBT families.

Bullying Statistics

It Gets Better Project

In Focus

Gay-Friendly Campuses

“What campuses do you consider to be LGBT-friendly?” This question was posed by the editors of the Advocate College Guide for LGBT Students. In 2006, the editors collected nominations from current LGBT college students as well as additional information from interviews with students and faculty or staff members from the nominated schools.

The editors based their final selections on 10 criteria, as reported in the guide. According to editor Bruce Steele, the editors intended to assess “the effort that’s being put forth by the colleges themselves to make their LGBT students comfortable” (Rosenbloom 2006:S2). The 10 criteria are as follows:

- Active LGBT student organization(s) on campus. Prospective LGBT students are looking for a sense of community with their peers and organizations that can offer social, educational, and leadership opportunities on campus.

- Out LGBT students. Prospective students look for other LGBT students to be visible and active in academic and campus life settings.

- Out LGBT faculty and staff. LGBT faculty and staff can serve as advisers and visible role models for LGBT students.

- LGBT-inclusive policies. Supportive campuses should have policies that include “sexual orientation” in their discrimination policy or have policies supporting same-sex domestic partner benefits.

- Visible signs of pride. The prominent presence of rainbow flags and pink triangles can create a sense of openness, safety, and inclusion.

- Out LGBT allies from the top down. Support from college administrators and alumni is essential to LGBT students.

- LGBT-inclusive housing and gender-neutral bathrooms. Campuses may have options for LGBT-themed housing to foster a living and learning atmosphere for students.

- Established LGBT campus center. What committed campus resources are available for LGBT students and organizations?

- LGBT/Queer Studies academic major or minor. Students are looking for classes where they can learn about LGBT identity, politics, and history.

- Liberal attitude and vibrant LGBT social scene. LGBT students want to be accepted fully. Students may want to live on a campus or in a city that offers queer entertainment.

Based on these criteria, would your school qualify as a LGBT-friendly campus? How does your campus support LGBT students?

Exploring social problems

Support for Same-Sex Marriage

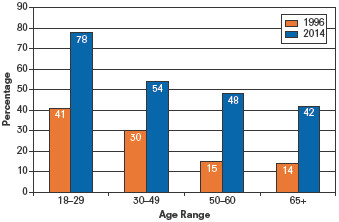

Figure 5.1 Percentage agreeing that same-sex marriage should be legal, by age, 1996 vs. 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from McCarthy 2014.

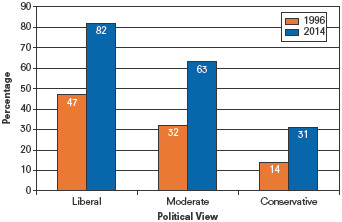

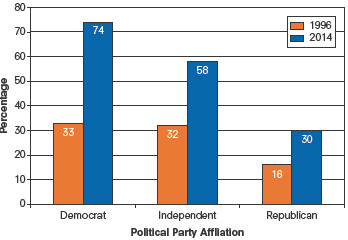

Figure 5.2 Percentage agreeing that same-sex marriage should be legal, by political views, 1996 vs. 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from McCarthy 2014.

Figure 5.3 Percentage agreeing that same-sex marriage should be legal, by political party affiliation, 1996 vs. 2014

SOURCE: Adapted from McCarthy 2014.

What Do You Think?

The majority of Americans support laws recognizing same-sex marriage.

According to a 2014 Gallup poll, 55% of those surveyed considered same-sex marriages legally valid, with the same rights as traditional marriage (McCarthy 2014).

Support for same-sex marriage varies by demographic characteristics, such as age (Figure 5.1), political views (Figure 5.2), and political party affiliation (Figure 5.3), and has changed over time.

Based on these graphs, what patterns in support can you identify?

Social scientists hypothesize that support for same-sex marriage increases as more individuals have contact or relationships with LGBT individuals. Sociologically speaking, why do you think contact with LGBT individuals increases support for same-sex marriage?

Voices in the Community

Dan Savage

After hearing the news of the suicide of Billy Lucas, a 15-year-old gay teen who reportedly endured bullying at school, Dan Savage and his husband, Terry Miller, posted a video about their lives—their family, their friends, and experiences they say they would have missed if they had killed themselves when they were bullied as teens.

Explaining how gay teenagers do not have access to positive gay role models, information, or resources, Savage wrote, “I wish I could have talked to this kid for five minutes. I wish I could have told Billy that it gets better. I wish I could have told him that, however bad things were, however isolated and alone he was, it gets better” (Savage 2010). Savage invited others to tell gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender teens how “it gets better” and submit their video to his YouTube channel. Savage (quoted in Chen 2012) explains,

The goal is to build and maintain these videos and all the support in them for LGBT kids who are growing up right now: 13-, 14-, and 15-year-olds; people who are nine years old right now but who will see these videos in five to six years. We want to make sure that videos are still being made and that LGBT kids know how to find these videos, how to find us.

Dan Savage (l) is pictured here with his husband Terry Miller (r). The couple married in 2012 afer Washington voters passed a ballot initiative extending marriage rights to same-sex couples.

Cliff DesPeaux/REUTERS

As described on its website, the It Gets Better Project has become a worldwide movement, with more than 50,000 personal videos reminding LGBT teens that they are not alone and that it will get better. Celebrities, politicians, professional athletes, and activists have posted their submissions.

Visit the website at www.itgetsbetter.org.

Military Service

During his first presidential campaign, Bill Clinton promised to extend full civil rights to gays and lesbians, including those in military service (Belkin 2003). The military policy at that time banned gay and lesbian individuals from the armed forces, stating that homosexuality was incompatible with military service. (For information on gay military service in other countries, refer to this chapter’s Taking a World View feature.) In 1993, President Clinton suspended the policy, and the National Defense Authorization Act became law.

Part of the law is the infamous “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy, a political compromise criticized since its inception. According to the policy, known homosexuals were not allowed to serve in the U.S. military, but the military was banned from asking enlistees questions about their sexual orientation. In addition, significant restrictions were placed on commanders wanting to investigate whether a soldier was gay (the complete policy is actually “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue, Don’t Harass”). Service members who disclosed that they were homosexual were still subject to military discharge. Between the inception of DADT and the end of 2009, more than 13,000 service members were discharged (Servicemembers Legal Defense Network 2007); from World War II to the repeal of DADT, an estimated 114,000 military personnel were discharged because of their sexual orientation (Burke 2013). It is not known how many gay and lesbian service members did not reenlist because of the policy without revealing their homosexuality.

In 2007, John Shalikashvili, retired Army general and former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, declared his support for the repeal of the DADT policy. Shalikashvili (2007) described how his conversations with gay soldiers and marines, some with Iraq combat experience, “showed me how much the military has changed, and that gays and lesbians can be accepted by their peers” (p. A19). He also cited evidence from a recent poll of 500 service members returning from service in Afghanistan and Iraq, indicating that 75% of those surveyed were comfortable interacting with gay people. In the same year, the Pentagon revealed that 58 Arabic-language experts had been discharged from military service since the inception of the policy because they were gay. U.S. House representatives were critical of the Pentagon, believing that the policy and its actions were homophobic rather than focused on the country’s national security needs.

A congressional bill to repeal DADT was enacted in December 2010. In 2011, a ruling from a federal appeals court barred further enforcement of DADT. DADT ended on September 20, 2011. In their assessment of the repeal of DADT, Aaron Belkin and his colleagues (2012) concluded that the repeal “has had no overall negative impact on military readiness or its component dimensions, including cohesion, recruitment, retention, assaults, harassment, or morale. . . . [G]reater openness and honesty resulting from the repeal seem to have promoted increased understanding, respect and acceptance” (p. 4). It is estimated that gay, lesbian, and bisexual service members make up at least 2% of the U.S. military’s active duty and reserve forces (Bumiller 2012). In 2013, the Defense Department announced that it would provide spousal and family benefits to the same-sex spouses of military personnel and other employees.

Repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Taking a World View

Gay Military Service Policies

In addition to the United States, the NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and non-NATO countries whose militaries have lifted their bans on gay military service are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom (Belkin 2003). Turkey is the only NATO country that does not permit gays and lesbians to serve openly in the military.

Aaron Belkin (2003) examined the early experiences of four countries that lifted their bans on homosexual military personnel. In each country—Australia, Canada, Israel, and Great Britain—the bans were lifted with opposition from the military services.

Belkin explains that each country lifted its ban for different reasons. In Canada, the ban was lifted in 1992, after federal courts ruled that the military policy violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The ban was also lifted in 1992 in Australia, when Prime Minister Paul Keating argued that the ban was not consistent with his country’s integration of several international human rights conventions into its domestic laws and codes. Israel’s military ban was lifted in 1993 after public response to Knesset hearings on the matter. In 1999, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Great Britain’s gay ban violated the right to privacy guaranteed in the European Convention on Human Rights.

All military personnel, academics, veterans, politicians, and nongovernmental observers interviewed for Belkin’s research did not believe that lifting the gay bans undermined “military performance, readiness, or cohesion, lead [sic] to increased difficulties in recruiting or retention or increased the rate of HIV infection among the troops” (Belkin 2003:110). Grim predictions and anxiety about how military personnel would refuse to work with or share showers, undress, or sleep in the same room with gay soldiers were not substantiated in these countries. Many interviewed described the policy change as a “non-event” or “not that big a deal for us” and said that the change was “accepted in ‘true military tradition’” (Belkin 2003:110–11).

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Defense allowed gay soldiers to march in their uniforms in a gay pride parade for the first time in U.S. history.

AP Photo/Gregory Bull

Interviewed military leaders stressed how all soldiers were held to the same standard of professional conduct regardless of sexual orientation or personal beliefs about homosexuality. Belkin (2003) states that none of the four militaries attempted to force military personnel to accept homosexuality. Data from the four countries confirm that soldiers refrained from the abuse and harassment of homosexual military personnel, though gay bashing and sexual harassment cases were documented in two of the countries (Australia and Israel).

During the war with Iraq, before the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” U.S. forces served side by side with allied forces from nine countries that allowed gays and lesbians to serve openly. In some cases, these forces worked together in integrated units (Servicemembers Legal Defense Network 2007).

From a social constructionist perspective, how was the repeal of gay military service bans (not just in the United States) framed by supporters and opponents? What was the social problem both sides were trying to address?

Sociology at Work

Internships and Service Learning

Experiential learning allows students to learn from direct experience. It is the process of learning by doing, also referred to as active learning. There are two types of experiential learning opportunities that can help you learn more about yourself and help refine your professional goals.

An internship is described as a pre-professional experience. A student is employed in an organization to learn job or career skills specific to an organization (social service office) or occupation (social worker). Internships may be paid or unpaid, full-time or part-time, completed with or without academic credit. Through your internship, you gain on-the-job experience to include on your resume.

Service learning is defined as “an educational experience involving an organized service activity with structured reflection to guide students’ learning” (Bringle and Hatcher 1999). Usually partnering with a community organization or program, students provide a range of services such as painting, cleaning, food service, or working with individuals or families. According to Sam Marullo (1996), service learning “bridges theory and practice, offering a crucible for learning that enables students to test theories with life experiences, and forces upon them an evaluation of their knowledge and understanding grounded in their service experience.”

Internships or service learning should not be confused with volunteer community service. If you are a weekend volunteer at your local soup kitchen, no one will expect you to write a paper about your experiences. Experiential learning includes an academic component or expectation. As part of your experience, you may be assigned readings and required to write a final project, paper, or reflection journal.

Investigate your department or school’s experiential learning options. Some departments manage their own list of internship placements or may coordinate with an internship or service learning office. Consider the experience you will gain and the work skills you can develop. Marullo (1996) says that through these experiential learning experiences,

critical thinking skills are enhanced because students are forced to confront simplistic and individualistic explanations of social problems with the complex realities they see in their volunteer work. Real world problems and constraints help students to develop their problem solving skills. Students’ conflict resolution skills are developed because the situations in which they serve are rife with conflict.

What type of internship or service learning experience would you like to explore?

Chapter Review

- 5.1 Define sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is defined as the classification of individuals according to their preference for emotional-sexual relationships and lifestyle with persons of the same sex (homosexuality) or persons of the opposite sex (heterosexuality). Bisexuality refers to emotional and sexual attractions to persons of either sex.

- 5.2 Describe how each sociological perspective addresses sexual orientation and inequality

Functionalists identify how society upholds heterosexuality and a marital union between a man and a woman as ideal normative behavior. This is also referred to as institutionalized heterosexuality, the set of ideas, institutions, and relationships that define the heterosexual family as the societal norm. From a conflict perspective, heterosexuals are granted a privileged place in our society. Heterosexual privilege is defined as the set of privileges or advantages granted to some people because of their heterosexuality. Feminist scholars have argued that lesbian and gay marriages will positively disrupt the gendered definitions of marriage. Interactionists examine how sexual orientation is constructed within a social context. The development of a gay identity has familial, social, legal, financial, religious, and health implications.

- 5.3 Explain the expansion of the rights and recognition of same-sex couples in the United States

The legal recognition of same-sex couples began incrementally at the federal level. In the 2010 Census, same-sex marriages, unions, and partnerships were counted for the first time. Legalization of same-sex marriage has been recognized in more than 20 states, along with expansion of adoptions, second-parent adoptions, and stepparent adoptions for same-sex couples.

- 5.4 Examine whether children raised by gay or lesbian parents have different life outcomes compared to children raised by heterosexual parents

According to academic research, there is little or no evidence that the children of gay or lesbian parents are disadvantaged in any important way in comparison with children of heterosexual parents. Children raised by gay or lesbian parents have no increased gender-identity problems and are just as well socially adjusted as children raised by heterosexual couples.

Key Terms

- bisexuality, 124

- heterosexism, 126

- heterosexuality, 122

- homophobia, 125

- homosexuality, 122

- institutionalized heterosexuality, 125

- LGBT, 124

- master status, 129

- sexual orientation, 122

- transgender, 124

Study Questions

- Compare and contrast the biological, psychological, and sociological perspectives on sexual orientation.

- Examine how heterosexuality is privileged in society.

- How, from a sociological perspective, is our sexuality defined/controlled by our norms, values, and language?

- Explain the role of power and privilege in understanding sexual orientation.

- How has repeal of the military policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” affected military service by gays and lesbians?

- Explain how gays and lesbians are discriminated against in the workplace and in the military.

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.