Chapter 4 Gender

Learning Objectives

- 4.1 Explain the difference between sex and gender

- 4.2 Describe how the different sociological perspectives explain problems related to sex and gender

- 4.3 Distinguish the two types of occupational segregation

- 4.4 Explain human capital theory

- 4.5 Compare the four feminist waves

In 2012, an all-male panel testified on Capitol Hill on the Blunt Amendment, a proposed federal policy exception that would have allowed religious groups and employers to opt out of providing any kind of health care service, including contraception, for religious reasons. The photo of the panel was widely distributed in the media, often accompanied by the headline “What is wrong with this picture?” The exclusion of a female voice on a panel on contraception stirred up a firestorm. Two female House representatives walked out of the hearing. House representatives followed with their own hearing featuring one female witness, Georgetown student Sandra Fluke, who had been turned away from the original hearing. Democrats argued that Republicans were turning back the clock on women’s rights (Pear 2012).

There is no society where men and women perform identical functions, nor are they ranked or treated equally. Regardless of their level of technological development or the complexity of their social structure, all societies have some form of gender inequality (Marger 2008). Some may argue that there are fundamental differences between males and females based on fixed physiological differences or our sex. Yes, there are biological differences—our sexual organs, our hormones, and other physiological aspects—that are relatively fixed at birth (Marger 2008), but more than that makes us unequal.

Sociologists focus on the differences determined by our society and our culture, our gender. Although we are born male and female, we must understand and learn masculine or feminine behaviors. Gender legitimates certain activities and ways of thinking over others; it grants privilege to one group over another (Tickner 2002). Sexism refers to prejudice or discrimination based solely on someone’s sex or gender. Although sexism has come to refer to negative beliefs and actions directed toward women, men can also be subject to sexism.

Social scientists believe that gender differences are not caused by biological differences; rather, they are a product of socialization, prejudice, discrimination, and other forms of social control (Bem 1993). For example, religious ideologies can define and regulate gender differences. According to Islamic tradition, women are relegated to home and family life, while men dominate everything outside the home. A strong patriarchal system is enforced among Mormon fundamentalists in the United States.

Consider the history of women in the U.S. Senate. There is nothing automatic at birth that makes men more suited to become senators than women. The first woman senator was Rebecca Latimer Felton, sworn into office on November 21, 1922. The Georgia senator was appointed to fill a vacancy and served for only one day. In the early 1990s, there were only two women senators. In 1992, Patty Murray, from my home state of Washington, was the first elected woman senator to have young children at home during her term in office (Stolberg 2003). A record number of 20 women were elected to serve in the 2013 U.S. Senate.

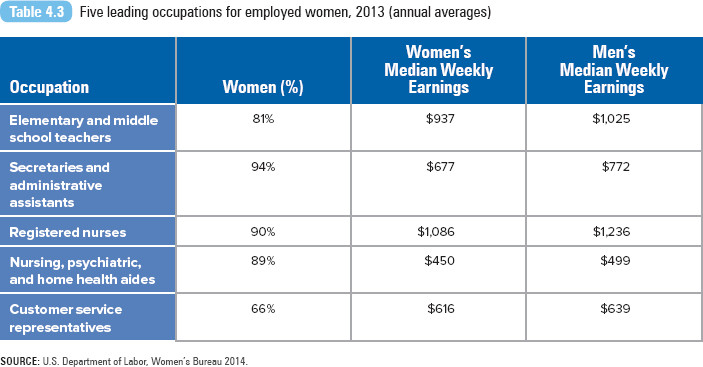

SOURCE: Adapted from Inter-Parliamentary Union 2014.

NOTE: In the list compiled by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (2014), the United States ranks 72nd; 19.4% of seats are held by women.

On January 4, 2007, U.S. representative Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) was elected Speaker of the House, the first woman to fill this role in the history of the House of Representatives. Pelosi was second in line for the succession of the presidency, after the vice president. On the day of her induction, Pelosi not only noted how her election was an important victory for her party but also acknowledged the importance of her election for women. She said, “For our daughters and granddaughters, today we have broken the marble ceiling. For our daughters and our granddaughters now, the sky is the limit” (Pelosi 2007). Yet a few months later, as Pelosi celebrated Women’s History Month, she is quoted as saying,

Women want what men want: an equal opportunity to succeed, a safe and prosperous America, good paying jobs, better access to health care, and the best possible education for our children. . . . Yet in terms of policies to assist women, we are lagging behind. Paychecks for women have dropped three years in [a] row by almost $1,000. On average, working women earn only 77 cents for every dollar working men earn, and over the last five years, the number of women living in poverty has grown by almost 3 million. (Pelosi 2007)

Despite the record number of women serving in Congress, the United States is behind other countries in female representation in national parliament or congress. Refer to Table 4.1 for more information.

Changing Gender Roles

Sociological Perspectives on Gender Inequality

Functionalist Perspective

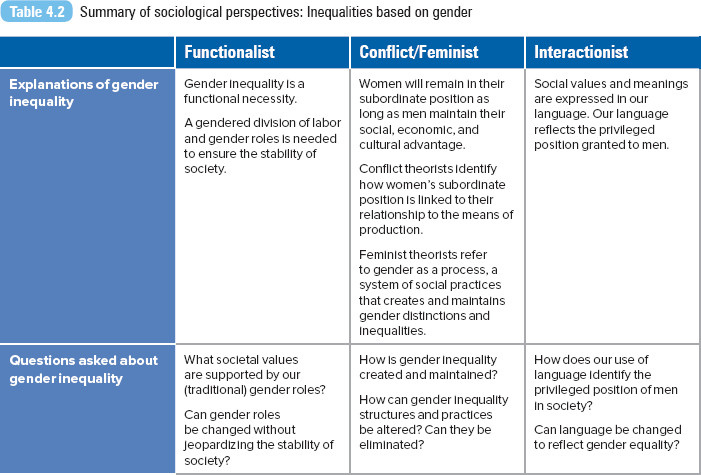

Functionalists argue that gender inequality is inevitable because of the gendered division of labor in the household. According to Émile Durkheim, social evolution led to the exaggeration of sex differences in personalities and abilities. In the most basic of social institutions, the family, it became necessary for men and women to establish role differentiation as well as functional interdependence. In other words, men and women would have complementary but different roles in the household.

Durkheim (2007) wrote of the biological differences between men and women, claiming that women had smaller brain capacity than males: “Woman retired from warfare and public affairs and consecrated her entire life to her family” (p. 43). As a result, women led completely different lives than men. This division of labor applied both in and out of the home—women were charged with familial roles, taking care of their children and their home, while men were charged with public work roles, assuming their primary role as family breadwinner. Although this division of labor may have been practical in preindustrial society, these roles remain gender specific in modern society (Marger 2008). Though women have transitioned from a housekeeper role to a dual role of earner and caregiver, men’s involvement in domestic work remains low.

The principle that women and men are suited for different roles extends to the workplace. Women dominate service and caring professions (e.g., teaching, health care, sales, and administrative support), while men are overrepresented in instrumental work (e.g., construction, heavy labor, and mechanics). Even in the same professions, men and women are on different professional tracks. Among medical students, women choose primary care specialties, while a higher percentage of men choose surgical specialties. Women place a greater emphasis on the physician–patient relationship than men (McFarland and Rhoades 1998). For more on occupational segregation, refer to the section of this chapter titled “The Consequences of Gender Inequality.”

This gendered division of labor and gender roles is held as the standard for society. Gender inequality is defined not as a product of differential power but rather as a functional necessity (Marger 2008). Yet women who assert their rights for social and economic equality are seen as attacking the structure of society (Bonvillian 2006). Theorists from this perspective note that as increasing numbers of women have entered the workforce, the number of divorces and the frequency of nonmarital childbearing have also increased. They suggest that children are more likely to suffer from divorce, more likely to become delinquent without adequate parental supervision, and more likely to be disadvantaged economically and socially if born to a single mother (Bonvillian 2006; Farley 2005). According to a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, most Americans believe that the increase in the number of working women has made it harder for parents to raise children and harder for marriages to succeed (Wang, Parker, and Taylor 2013). From this perspective, a change in gender roles (among women in particular) undermines the stability of the family (Farley 2005) and, ultimately, society.

Tough Guise

Conflict and Feminist Perspectives

Gender inequality exists because it benefits a group in power and with power to shape society—men. Theorists from both perspectives argue that women will remain in their subordinate position as long as men maintain their social, economic, and cultural advantage in society. A system where men are dominant over women is referred to as a patriarchy, as defined earlier in Chapter 1.

Women’s subordinate position in society is linked to their relationship to the means of production. As the next section of this chapter describes, compared with women, men are rewarded in our capitalist economy with higher wages, more prestige, and greater authority in the workplace (Bonvillian 2006). At home, men are treated with deference by their wives and children.

Bonvillian (2006) explains the interrelationship between patriarchal social relations and capitalist economies. As capitalistic economies developed, they incorporated preexisting patriarchal relations. Capitalism benefits from women’s subordinate position at home. Women are willing to work in different types of jobs and for different wages than men because they define themselves according to their familial relationships as supporters rather than as breadwinners.

Capitalism also takes advantage of men’s adherence to patriarchal values, subordinating men to their employers just as patriarchal relations subordinate women to men. Men are duty bound to their jobs because of a sense of self-worth and obligation tied to their ability to provide for their families (Bonvillian 2006). As men are limited to their prescribed positions in the economy and production, their inner emotional states are devalued in society. According to Böhnisch (2003), this limits the development of their full human potential (much like Marx cautioned), also contributing to a range of male problems (e.g., health and chronic illnesses, risk-taking, and violence).

Early feminist scholars treated gender as an individual attribute, as a property of individuals or as part of the role that was acquired through socialization. However, contemporary feminist theorists define gender as a system of social practices that creates and maintains gender distinctions and inequalities (Ridgeway and Smith-Lovin 1999). Gender is referred to as a process, where gender is continually produced and reproduced. Not only is this an individual characteristic, but also it exists within patterns of social interaction and social institutions (Wharton 2004).

Gender inequality is a product of a complex set of social forces: “These may include the actions of individuals, but they are also found in expectations that guide social interaction, the composition of social groups, and the structures and practices of the institutions” (Wharton 2004:157). Sexism may be an individual act, but it can also become institutionalized in our organizations or through laws and common practices.

True gender equality is possible only if women are able to assume positions of power in the economy and political system (Marger 2008) and redefine the structures and practices that oppress them. Though gender issues have been defined primarily as women’s issues, the call for integrating men’s issues into the discussion of gender inequality has become louder (Scambor and Scambor 2008). Structural inequalities between men and women don’t just discriminate against women. From this perspective, tackling gender inequality means questioning gendered structures at various levels (labor, child care, socialization, family) and addressing the experience of men and women equally.

Ambition and the Gender Pay Gap

Voices in the Community

Sandra Fluke

Sandra Fluke gained national celebrity status after she testified before Congress in 2012 about the importance of contraceptive coverage in health insurance. Her comments were mostly about how her university, Georgetown University, refused to include contraceptive coverage in student insurance plans because it was a religiously affiliated (Catholic) school. Before this day, Fluke had a long history as an advocate for women’s reproductive rights; Fluke is past president of the Georgetown Law Students for Reproductive Justice group.

Fluke explained that she wanted to tell the stories of women who did not have birth control:

I wanted to be able to share their stories. My testimony would have been about women who have been affected by their policy, who have medical needs and suffered dire consequences . . . The committee did not get to hear real stories I had to share, about actual women who have been dramatically affected by this policy. (Quoted in Kliff 2012)

Fluke spoke about a gay friend who had an ovary removed because her insurance company wouldn’t cover the prescription for birth control that she needed to control the growth of her cysts. “When you let university administrators or other employers, rather than women and their doctors, dictate whose medical needs are legitimate and whose are not, a woman’s health takes a back seat to a bureaucracy focused on policing her body” (Fluke 2012).

Vicious attacks from conservative radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh continued to keep Fluke in the media spotlight after her testimony. Fluke wrote on her Tumblr site,

Sandra Fluke gained national status after she testified before Congress in 2012 about the importance of contraceptive coverage in health insurance. Even before her testimony, Fluke had a long history as an advocate for women’s reproductive rights.

AP Photo/Nick Ut

No woman deserves to be disrespected in this manner. This language is an attack on all women, and has been used throughout history to silence our voices. The millions of American women who have and will continue to speak out in support of women’s health care and access to contraception prove that we will not be silenced. (Quoted in May 2012)

Limbaugh eventually apologized for his comments, but did not back down from his central argument that taxpayers’ money should not be used to pay for contraception.

After graduating from Georgetown, in 2014, Fluke unsuccessfully ran for office in the California State Senate.

From an interactionist perspective, what effect, if any, did Limbaugh’s comments have on Fluke’s testimony or public image?

Interactionist Perspective

As interactionists explain, many social values and meanings are expressed in our language. Language, write Stephanie Wildman and Adrienne Davis (2000), “contributes to the invisibility and regeneration of privilege” (p. 50). These scholars argue that we need to sort individuals into categories such as race and gender. Upon hearing that someone has a new baby, why is it important to ask if it’s a girl or a boy? This type of social categorization is important because it sets into motion the production of gender difference and inequality. Norms, values, and beliefs about the differences between boys and girls and men and women are reinforced through the gender socialization process. We won’t know how to relate to this child without knowing its gender, and children won’t understand what it means to be male or female in our society unless they are socialized accordingly. People respond to others based on what they believe is expected of them and assume that others will do the same (Wharton 2004).

Wildman and Davis note that characteristics of those who are privileged become societal norms—the standard of what is good, correct, and normal versus bad, incorrect, and aberrant. In terms of gender, men are privileged and serve as the standard. Wildman and Davis (2000) refer to Catharine MacKinnon’s observation that, among many things, “men’s physiology defines most sports, their health needs largely define insurance coverage . . . their perspectives and concerns define quality in scholarship, their experiences and obsessions define merit, . . . their image defines god, and their genitals define sex” (p. 54).

Male privilege defines many aspects of American culture from a distinctly male point of view. For example, the use of he is accepted as an all-inclusive pronoun, but a generic she is not permitted; some actually get upset if you try to use it (if you have any doubt, try referring to God as she). The response, according to Wildman and Davis, is not about incorrect grammar; rather, it is about challenging the system of male privilege.

A summary of the sociological perspectives is presented in Table 4.2.

Gender at the Toy Store

The Consequences of Gender Inequality

Gender inequality is a persistent feature of all modern societies. In this section, we will review the consequences of inequality in women’s employment and income. Additional discussions on gender inequality are presented in Chapter 8, “Education,” and Chapter 9, “Work and the Economy.” The section ends with an examination of violence against women.

The U.S. labor force continues to be segregated along gender lines. Although a small percentage of women, 25% or less, are employed in traditionally male blue-collar occupations (such as construction, truck driving, and manufacturing), women continue to dominate administrative (clerical) and service occupations, constituting more than 80% of employees in these occupations (U.S. Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau 2014).

AP Photo/Elaine Thompson

Occupational Sex Segregation

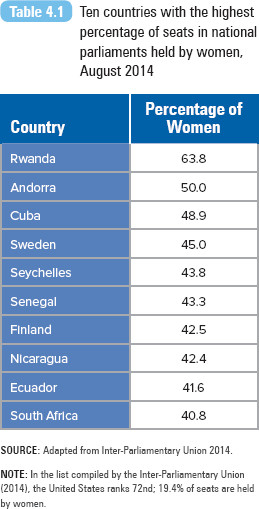

Sex segregation in the workplace remains a historical and contemporary fact. Despite educational and occupational gains made by women, women continue to dominate traditionally female occupations, which is referred to as occupational sex segregation. These occupations include preschool and kindergarten teachers (98%), child care workers (95%), and receptionists (92%) (U.S. Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau 2014). For the top five occupations of employed U.S. women, refer to Table 4.3. Researchers confirm that working in an occupation with a large proportion of female workers leads to lower wages, lower prestige, worse working conditions, and slower career mobility for both men and women (Perales 2013).

Social scientists examine two types of sex segregation in the workplace—horizontal and vertical. Horizontal segregation represents the separation of women into nonmanual labor and men into manual labor sectors. Vertical segregation identifies the elevation of men into the best-paid and most desirable occupations in nonmanual and manual labor sectors, whereas women remain in lower-paid positions with no job mobility.

Maria Charles and David Grusky (2004) identify several social factors that promote and reproduce horizontal segregation. Employer and institutional discrimination help maintain the separation of women and men in the workplace, for example, by excluding women intentionally or unintentionally from physically strenuous jobs. The process of child socialization encourages girls and boys to internalize sex-typed expectations of others, which in turn shapes their occupational aspirations and preferences. Sociologists have examined how girls and boys are subject to differential gender socialization from birth. Traditional gender role stereotypes are reinforced through the family, school, peers, and the media with images of what is appropriate behavior for girls and boys. This includes defining appropriate occupations for women versus men.

Internalization of sex-typed expectations also leads workers to believe that if they transgress norms about gender-appropriate labor, they will be subject to sanctions (from disapproval from their parents to harassment from fellow workers). Years of horizontal segregation have given the advantage to men who have a disproportionate number of peers and network ties in the manual sector.

Vertical segregation is based on deeply rooted and widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more competent than women and are better suited than women for positions of power. According to Charles and Grusky (2004), vertical segregation is reproduced because it is consistent with the value of “male primacy.” In her analysis of vertical segregation among men and women on Wall Street, Louise Marie Roth (2006) discovered how the gendered division of labor in the family spilled over into the workplace. Wall Street’s workaholic culture assumes that the ideal employee has no external (family) obligations, setting work as the primary priority. Since child care is defined as women’s responsibility, Wall Street women were routinely penalized for having families—women were expected to quit once they had children and were often treated differently after the birth of children. On the other hand, male Wall Street professionals were perceived as more committed and stable when they were married and had children. Roth concludes that males with traditional stay-at-home wives were able to maintain their ideal employee role.

Occupational sex segregation is a worldwide phenomenon. Many studies have examined segregation cross-nationally and have found that though it is a feature of all industrial societies, the degree to which it exists varies. In her analysis of vertical and horizontal segregation in 10 countries including the United States, Charles (2003) found that women were underrepresented in the manual sector and that within the manual and nonmanual sectors, women’s occupations were of lower average status. She reports the highest levels of horizontal segregation in Sweden and France, where women are about 30 times more likely to work in white-collar than in blue-collar sectors. The likelihood is lower in the United States—women are 14 times more likely to work in white-collar sectors. The highest levels of vertical segregation were found in France and in the United Kingdom. Vertical segregation for the United States was third lowest among the 10 countries Charles examined. The countries with the lowest levels of horizontal and vertical segregation were Portugal and Italy, which Charles attributed to the countries’ development of two main occupational groups—professionals and craft-operations workers.

Jane Elliot’s (2005) research revealed that there was greater occupational segregation between men and women and between full-time and part-time working women in the United Kingdom than in the United States. She characterizes employed women in the United Kingdom as having a “returner” pattern of labor participation (periodic employment vs. continual employment as in the United States) and notes that UK women are primarily concentrated in occupational groups that rely on part-time labor. UK labor laws encourage the hiring of part-time employees versus full-time employees, which encourages women’s employment patterns. Elliot suggests that UK women may be less attached to their employment than U.S. women are because national health services are available regardless of employment. In the United States, one’s employer usually provides health insurance.

Income Inequality

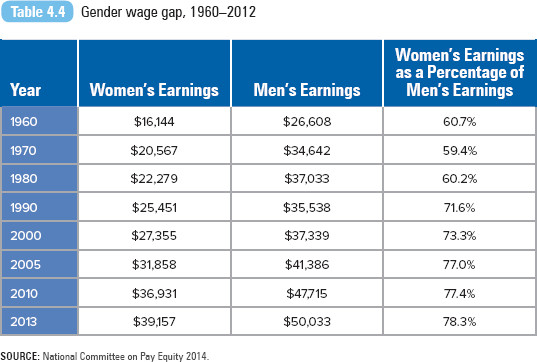

According to the National Committee on Pay Equity (2014), in 2013, for every dollar earned by a man, a woman made 78.3 cents (refer to Table 4.4 for wage gap data from 1960 to 2013). U.S. Data Map 4.1 reports the wage gap between women and men by state. Another way to measure the earning difference is to examine wage ratios, comparing the annual earnings of women and women who work full-time all year—what is the difference in men’s and women’s lifetime earnings? Stephen Rose and Heidi Hartmann (2004) examined data for 1983 to 1998 and concluded that women workers in their prime earning years make 38% of what men make. During the 15-year period, an average prime-age working woman earned only $273,592 compared with $722,693 earned by the average working man (in 1999 dollars). (For information regarding the gap between college men and women graduates, turn to this chapter’s In Focus feature.)

Why do men earn more? Social scientists have attempted to answer the question, offering different explanations for the earning gap. Some have emphasized the role of human capital, the knowledge and skills workers acquire through education, training, and work experience. Human capital theory suggests that women earn less than men do because of differences in the kind and amount of human capital they acquire (Wharton 2004). Because their labor force participation is assumed to be interrupted by marriage and child-rearing responsibilities, most women will invest less in their job-related human capital or will choose occupations that provide flexible hours or lesser penalties after reentry (e.g., teaching). In the United States, women do have less continuous work experience than men do; their labor is interrupted by childbirth and child rearing. Yet, research indicates that even among women with continuous work experience, their earnings are less than men’s (England 2001).

Another explanation offered by social scientists focuses on the devaluation of women’s work. A higher societal value is placed on men than on women, and this is reproduced within the workplace. Caring or emotional labor is undervalued and defined as women’s work, while professional or corporate skills are valued and defined as men’s work. The relative worth of men’s and women’s economic activities is assessed within this value system, with men and masculine activities being valued more highly than women and feminine activities (Wharton 2004). According to Maume (1999), a higher value is granted to male occupations or job skills, permitting discrimination against the type of jobs women do, but not against women themselves.

In 2007, the Supreme Court limited workers’ ability to challenge wage discrimination in court. The Supreme Court ruled that employees could not challenge ongoing compensation discrimination if the employer’s original discriminatory act or decision occurred more than 180 days earlier. Prior to this decision, each discriminatory paycheck was treated as a separate discriminatory act and reset the 180-day clock allowed for filing a claim. In the original case, Lilly Ledbetter, an area manager at Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, charged that she was paid less than her 15 male counterparts. Ledbetter was paid $3,727 per month, and the lowest-paid male manager received $4,286 per month. Though a jury awarded Ledbetter $3.3 million in damages, the court of appeals reversed the verdict, stating that her case was filed too late.

At the signing of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, President Obama stated that the issue of fair pay isn’t just a women’s issue. According to Obama, the bill ensures that all Americans are able to make a living and provide for their families. The law’s namesake was at the president’s side at the signing of the act (she is shown standing behind him, just to his right, in this photo).

Whitehouse.gov

The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act was signed into law by President Barack Obama in January 2009. The act reinstated the prior law that allowed pay discrimination claims on the basis of sex, race, national origin, age, religion, and disability to accrue whenever an employee received a discriminatory paycheck. At the signing of the bill, Ledbetter acknowledged that she would not receive any money as a result of the law named after her. “Goodyear will never have to pay me what it cheated me out of . . . . But with the president’s signature today I have an even richer reward” (quoted in Stolberg 2009).

Examining the Pay Gap

Exploring social problems

The Wage Gap

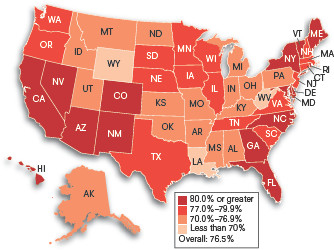

U.S. Data Map 4.1 Gender wage gap by state as ratio of median earnings for women and men working full-time, year-round, 2012

SOURCE: National Women’s Law Center 2013.

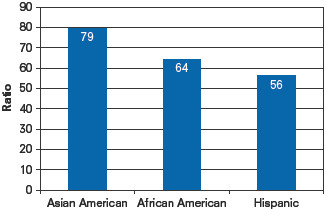

Figure 4.1 Ratio of median earnings for minority women working full-time, year-round, 2013

SOURCE: National Women’s Law Center 2014a.

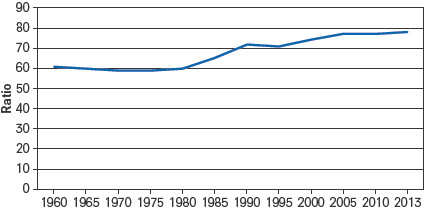

Figure 4.2 Ratio of median earnings for women and men working full-time, year-round, 1960–2013

SOURCE: National Women’s Law Center 2014b.

What Do You Think?

The wage gap is largest in Wyoming (63.8), Louisiana (66.9), and West Virginia (66.9). The states with the smallest wage gaps are Maryland (85.3), Nevada (85.3), and New York (83.9). Where does your state rank?

Overall, the wage gap is 78 cents. However, the wage gap is larger for African American and Hispanic women (refer to Figure 4.1). As presented in Figure 4.2, progress on the wage gap has been slow. The lowest ratio was recorded in the 1970s. A woman working full-time, year-round made 59 cents for every dollar paid to her male counterpart.

Which sociological theories offer the best explanation for why the gender wage gap still exists?

Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Assault

A global review of scientific data on the prevalence and effects of intimate partner violence and sexual violence by someone other than a partner was cosponsored by the World Health Organization, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the South African Medical Research Council. Results of the collaborative review were released in 2013, documenting the continuing violence against women and recommending how health agencies and programs should respond (World Health Organization 2013).

Based upon selected published literature since 2008 and multi-country surveys, the researchers estimated that 35% of women worldwide suffer physical or sexual violence, with the most common form of abuse being physical violence inflicted by an intimate partner. Globally, only 7% of women have been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner. The systematic killing of women, femicide, is different from the murder of men and often involves sexual violence. As many as 38% of all murders of women are committed by a husband or boyfriend.

In 2006, the United Nations attributed violence against women to historically unequal power relations between men and women and pervasive discrimination against women. Violence, said the United Nations, “is one of the key means through which male control over women’s agency and sexuality are maintained” (United Nations 2006:1). Violence against women is not confined to one nation, culture, or region; however, a woman’s personal experience of violence is likely to be shaped by her ethnicity, class, age, sexual orientation, disability, nationality, and/or religion.

The 2013 World Health joint report identifies intimate partner violence as a major contributor to women’s problems related to mental health, sexual and productive health, maternal health, and neonatal health. For example, women who experience partner violence are more than twice as likely to experience depression and in some areas are 1.5 times more likely to acquire HIV than women who do not suffer partner violence. The authors concluded,

The findings underpin the need for the health sector to take intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women more seriously. All health-care providers should be trained to understand the relationship between violence and women’s ill health and to be able to respond appropriately. . . . This evidence highlights the need to address the economic and sociocultural factors that foster a culture of violence against women. (World Health Organization 2013:35–36)

In Focus

The Pay Gap Between College-Educated Men and Women

In 2012, women working full-time still earned just 75.6% of what men earned. In separate analyses of data from the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Department of Education, the Economic Policy Institute (a nonprofit nonpartisan think tank) and the American Association of University Women (AAUW) Educational Foundation revealed surprising earning disparities between men and women college graduates. Though the wages of college-educated women had grown rapidly since 1979, in 2009 a female college graduate earned 82% of what a male college graduate made (AAUP 2013; Mishel, Bernstein, and Allegretto 2007). One year out of college, women working full-time earn only 80% as much as their male peers. Ten years after graduation, women’s earnings drop to 69% of men’s. Despite controlling for hours of work, occupational type, and family status, college-educated women still earn less than college-educated men (Dey and Hill 2007).

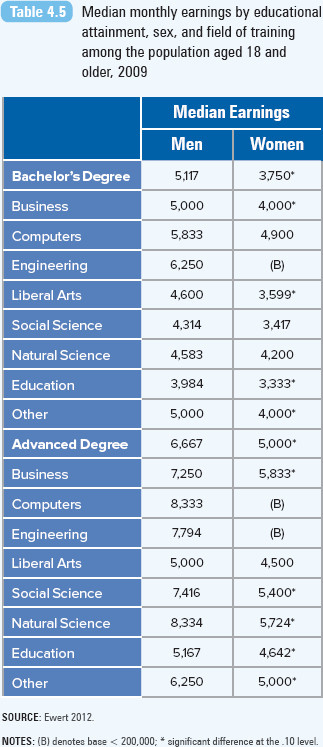

A 2012 report by the U.S. Census Bureau also documented the persistent wage gap between college-educated men and women (refer to Table 4.5). Women earned less per month than men at every degree level and in all fields of training. Stephanie Ewert (2012) highlighted the progress made by women in the natural sciences. In this field, men’s and women’s median monthly earnings did not significantly differ at the bachelor’s degree levels (and associate’s degree, not shown here), but women still earned significantly less than men at the advanced degree level.

Though men and women pay the same amount for their college education, since they do not reap the same pay rewards after graduation, women’s debt burden is greater than it is for men (AAUP 2013).

How can we resolve the gender pay gap? At the individual level? At the employer level?

SOURCE: Ewert 2012.

NOTES: (B) denotes base < 200,000; * significant difference at the .10 level.

Responding to Gender Inequalities

Feminist Movements and Social Policies

Historians mark the beginning of the feminist movement in the United States and throughout the world in the 19th century. The U.S. feminist movement began in 1848 with the first Women’s Rights Convention. A group of women, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, adopted a declaration of sentiments demanding, among other things, women’s right to vote. During the same time, the women’s suffrage movement began in Great Britain, with increasing demands for women’s political and economic equality. The Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 affirmed for U.S. women the right to vote. In Great Britain, women were given the right to vote in 1918.

The feminist movement has been defined in “waves,” the first beginning in the 19th century, followed by the second during the 20th century. Politically, the second wave focused on expanding legal rights for women. During this period, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, prohibiting sexual harassment in the workplace and providing equal workplace opportunities for women and minorities (refer to Chapter 3, “Race and Ethnicity,” for a discussion on affirmative action in employment and education), and Title IX of the Education Amendments was passed in 1972 (refer to the next section). Still, the movement was unsuccessful in passing the Twenty-Seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which proposed, “Equality of rights under law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any state, on account of sex.” Though passed by the U.S. Congress in 1972, it was not ratified by the required 38 states to become a constitutional amendment. In 1977, Indiana became the 35th state to ratify the amendment. ERA ratification bills have been introduced in the remaining states without any success.

The third wave of feminism began in the 1990s. Though second-wave feminists are credited with achieving greater gender equality, they are criticized for assuming the universalization of the White woman’s experience and for focusing exclusively on oppression based solely on sex. The third wave of feminism attempts to address multiple sources of oppression—acknowledging oppression based on race and ethnicity, social class, and sexual orientation in addition to sex. Instead of focusing on gender equality within one country or nation, the focus has expanded to a goal of global equality. Some third-wave activists even distance themselves from the use of the term feminist, believing the term is too confining or negative.

A fourth wave of feminism has been noted in scholarly and popular literature. The wave is defined in various ways. Brazilian sociologists Solange Simões and Marlise Matos (2009) define the term as a process of gendered democratic institutionalization and policy making, which includes a “revitalization of a classic feminist rights agenda under the influence of transnational feminism and the globalization of local women’s agendas” (p. 95). The fourth wave synthesizes the second wave’s emphasis on equality and the third wave’s focus on global inequality. Fourth-wave feminism has also been described as a movement without one cohesive cause, leader, or platform. Younger women, to whom equality and rights have always been granted, seek new ways to remain politically and socially engaged (e.g., the Internet).

The European Union, since the late 1990s, has embraced gender mainstreaming as its main strategy to address inequalities between men and women. It is defined as the integration of the gender perspective into every stage of the policy process (design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation). Before this, gender equality policies focused primarily on the experience of women. In contrast, gender mainstreaming explicitly addresses the experiences of men, such as parental leave as a jurisdictional claim for men or labor policies for men in female-dominated occupations (e.g., nursing) (Scambor and Scambor 2008). Gender mainstreaming can also apply to health care, equally promoting women’s and men’s health care needs (Kuhlmann and Annandale 2012). In many countries, coronary heart disease is defined through a masculine lens, influencing all areas of medical care from prevention to rehabilitation. Though this leads to overlooking women’s cardiac needs, it also may negatively impact men who do not seem to fit the model of hegemonic masculinity (Riska 2010).

Taking a World View

Leaving No Girl Behind

Malala Yousafzai was shot in the face at point-blank range by a masked Taliban gunman on her way to school. This 15-year-old girl was targeted for advocating girls’ education in Pakistan. As an 11-year-old, she had faced the media and criticized the Taliban for taking away her basic right to education. She said into the camera, “You may stop me from going to school, but you will not stop me from learning.” The assassination attempt transformed Malala into a global ambassador and advocate.

Despite overall progress in girls’ educational access and achievement, a generation of young women has been left behind. This is the conclusion that has been made by the United Nations Girls Education Initiative (UNGEI) (2013a). In 2011, there were 31 million girls out of school; 55% are expected never to enroll. The UNGEI estimates that women account for almost two thirds of the world’s illiterate population.

UNGEI attributes the lack of girls’ educational participation to structural factors, namely, values and norms that discriminate against girls, preventing them from attending and remaining in schools. Even in areas where they enroll in equal numbers in primary education, girls are likely to drop out before reaching secondary education due to child marriage, early pregnancy, gender-based violence in schools and at home, and the burden of domestic labor (UNGEI 2013b).

Malala Yousufzai was honored with the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014. At 17 years of age, Yousufzai is the youngest Nobel recipient.

Southbank Centre

Research has demonstrated how education improves women’s economic security in the world’s poorest countries “and makes it more likely [for women] not just to be employed, but also to hold jobs that are more secure and provide good working conditions and decent pay” (UNGEI 2013a:20). Public health workers have also observed how education improves the health of children. Educated women ensure that their children are vaccinated and are likely to practice preventative health measures, thus reducing infant and child mortality due to pneumonia or diarrhea.

After surviving her injuries, Malala and her family relocated permanently to the United Kingdom. Her father, Ziauddin, was named an adviser on global education by Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Malala established her own organization, Malala Fund, and continues to serve as an advocate for girls’ education. Malala was honored with the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize.

How else does education improve the quality of life for girls and young women?

Title IX

Among the achievements of the second wave of feminism was the passage of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Title IX of the Education Amendments prohibits the exclusion of any person from participation in an educational program or the denial of benefits based on one’s sex (Woodhouse 2002). The preamble to Title IX states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any educational programs or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

In 2013–2014, an estimated 3.2 million girls participated in high school sports programs. The top three sports were track and field, basketball, and volleyball. Title IX is credited with increasing girls’ participation in high school sports.

© Tim Clayton/30154666A/Corbis

In particular, the law requires that members of both sexes have equal opportunities to participate in sports and enjoy the benefits of competitive athletics (National Women’s Law Center 2002b). According to Title IX, schools receiving federal aid are required to offer women and men equal opportunities to participate in athletics. This can be done in one of three ways: schools demonstrate that the percentage of men and women athletes is about the same as the percentage of men and women students enrolled (also referred to as the “proportionality rule”), or the school has a history and a continuing practice of expanding opportunities for women students, or the school is fully and effectively meeting its women students’ interests and abilities to participate in sports. In addition, schools must equitably allocate athletic scholarships. The overall share of financial aid going to women athletes should be the same as the percentage of women athletes participating in the athletic program. Finally, schools must treat men and women equally in all aspects of sports programming. This requirement applies to supplies and equipment, the scheduling of games and practices, financial support for travel, and the assignment and compensation of coaches (National Women’s Law Center 2002a).

The law has been widely credited with increasing women’s participation in high school and collegiate sports and for women’s achievement in education. For instance, in the 1971–1972 season, 294,015 girls participated in high school athletics (comprising 7% of all high school athletes); by 2010–2011, the number had grown to nearly 3 million (41% of all high school athletes). In 1971–1972, 29,977 females participated in collegiate athletics (15% of all college athletes); by 2010–2011, the number exceeded 190,000 (44% of all college athletes) (National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education 2012). The representation of women in athletic leadership has also increased. In 2008, almost 15,000 women were employed in intercollegiate athletics, as athletic directors, coaches, or trainers. One out of five athletic directors is a woman, the highest representation since the mid-1970s (Acosta and Carpenter 2009). Regarding college enrollment, in 1973, 41% of women high school graduates were enrolled in college; in 2010 the percentage increased to 74% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2011).

After more than 35 years, the controversy regarding Title IX continues. Many blame Title IX for the demise of collegiate men’s programs. To achieve proportionality between the number of men and women athletes, schools have reduced the number of men athletes in minor sports programs such as wrestling, gymnastics, golf, and tennis (Garber 2002). However, according to the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education (2012), between the 1988–1989 and 2010–2011 school years, NCAA institutions added 3,727 men’s sports teams and dropped 2,748, for a net gain of nearly 1,000 teams. During the same period, 4,641 women’s teams were added and 1,943 were eliminated. Women made greater gains because they started with a deficit in the number of athletic teams. Evidence also indicates that not all colleges and universities are complying with the law. Although women in Division I colleges represent more than half the student body, women’s sports receive only 42% of athletic scholarships, 31% of recruiting funds, and 28% of operating budgets (National Women’s Law Center 2012).

On the 38th anniversary of Title IX in 2010, in addition to noting the progress made in women’s athletics, U.S. secretary of education Arne Duncan identified the need to ensure safe learning environments free from sexual violence and assault. Colleges and universities receiving federal funding are required under Title IX to respond promptly and effectively to sexual violence against students. This includes schools’ efforts to prevent sexual violence, the creation of enforcement strategies, and the implementation of investigation procedures. In 2014, President Barack Obama created the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, maintaining the administration’s commitment to ending sexual violence on college campuses. Later that year, the U.S. Department of Education released a list of 55 colleges and universities under investigation for possible violations over the handling of sexual violence and harassment complaints (U.S. Department of Education 2014).

Funding Sports Fairly

Sociology at Work

Sociology as a Science: Theory and Data

Your Sociology major requirements will likely include coursework in research methods and statistics. In your methods course, you’ll learn different ways to collect qualitative and quantitative data. You will use a data software program such as SPSS, SAS, or R to analyze your data. But the important skill that you’ll acquire is the ability to make sense of data, to analyze it, and to apply it.

One of my favorite sociology quotes comes from Peter Berger’s (1963) classic Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective: “Statistical data by themselves do not make sociology. They become sociology when they are sociologically interpreted, put within a theoretical frame of reference that is sociological” (p. 11). Although data are important in answering sociological questions, the data themselves do not constitute sociology (Berger 1963); it is you (the sociologist) that makes the data sociological.

For example, in this chapter we’ve reviewed the gender wage gap. In Table 4.4, wage gap data for 1960 to 2012 are presented. The data in the table are just numbers. Human capital theory, the devaluation of women’s work, or theories on vertical or horizontal segregation help us better understand the persistent wage gap between women and men. These theories identify how cultural beliefs, such as the belief that women will invest less in their employment due to marriage and childbearing responsibilities, are replicated in the workplace and reinforce gender income inequality.

Sociologists Kathleen Korgen, Jonathan White, and Shelley White (2011) explain the power of sociological research methods and their connection to sociological theory.

In order to make society better, we must first have a firm understanding of how and why it functions in the ways it does. Following the basic steps of scientific research helps us to see and measure patterns in society, so that we can better understand how it operates. Once we have done so, we can then begin to understand why it operates that way (through critical, sociological analysis and theories). (p. 39)

How is analyzing and understanding data an important work place skill?

Chapter Review

- 4.1 Explain the difference between sex and gender

Sex is based upon fixed physiological or biological differences, while gender refers to our masculine and feminine behaviors determined by our society or culture.

- 4.2 Describe how the different sociological perspectives explain problems related to sex and gender

According to functionalists, gender inequality is defined not as a product of differential power but rather as a functional necessity. Theorists from both conflict and feminist perspectives argue that women will remain in their subordinate position as long as men maintain their social, economic, and cultural advantage in society. From a conflict perspective, women’s subordinate position in society is linked to their relationship to the means of production. Contemporary feminist theorists refer to gender as a process, a system of social practices that creates and maintains gender distinctions and inequalities. From an interactionist’s perspective, language defines and maintains privilege in society; regarding gender, men are privileged and set many standards.

- 4.3 Distinguish the two types of occupational segregation

Horizontal segregation represents the separating of women into nonmanual labor and men into manual labor sectors. Vertical segregation identifies the elevation of men into the best-paid and most desirable occupations in nonmanual and manual labor sectors, whereas women remain in lower-paid positions with no job mobility.

- 4.4 Explain human capital theory

Human capital theory suggests that women earn less than men do because of differences in the kind and amount of human capital they acquire. The assumption is that women will invest less in their job-related capital due to marriage and child-rearing responsibilities.

- 4.5 Compare the four feminist waves

The first wave began in the 19th century, with women’s suffrage as its primary goal. The second wave began in the 20th century, with increased political focus on ensuring legal rights for women. The third wave of feminism began in the 1990s, attempting to address multiple sources of oppression and acknowledging oppression based on race and ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation, and sex. The emerging fourth wave synthesizes the second wave’s emphasis on equality and the third wave’s focus on global inequality. Fourth-wave feminism has also been described as a movement without one cohesive cause, leader, or platform.

Key Terms

- devaluation of women’s work, 109

- femicide, 113

- gender, 98

- gender mainstreaming, 115

- gendered division of labor, 101

- horizontal segregation, 106

- human capital, 109

- human capital theory, 109

- occupational sex segregation, 106

- sex, 98

- sexism, 100

- vertical segregation, 106

Study Questions

- What is the difference between sex and gender? How is gender socially constructed?

- Define sexism. Identify one example of institutional sexism.

- Examine occupational segregation from the functionalist and conflict perspectives.

- From an interactionist perspective, Wildman and Davis (2000) offer several examples of how our language privileges men over women. Can you identify cases of female privilege over men?

- The gender role socialization process reinforces our beliefs about the differences between men and women. Is it possible to raise boys and girls the same way, to be gender neutral in the socialization process? Why or why not?

- How do sociologists explain the wage gap between men and women? Do you think it is possible to reduce or eliminate the gap?

- Explain the importance of the four waves of feminism.

- We take special note of female firsts—the first woman secretary of state (Madeleine Albright), the first woman Speaker of the House (Nancy Pelosi), the first woman president of Harvard University (Drew Gilpin Faust), and the first woman to lead General Motors (Mary Barra). All these events occurred during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, two centuries after the beginning of the feminist movement. In your opinion, has the feminist movement been successful? What remains to be achieved? Would you describe yourself as a feminist? Why or why not?

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge at edge.sagepub.com/leonguerrero5e

SAGE edge provides a personalized approach to help you accomplish your coursework goals in an easy-to-use learning environment.