Chapter 3 Race and Ethnicity

Learning Objectives

- 3.1 Describe the difference between race and ethnic groups

- 3.2 Identify the different types of institutional discrimination

- 3.3 Summarize how the sociological perspectives explain problems related to race and ethnicity

- 3.4 Describe the impact of immigrant or illegal workers in the labor force

- 3.5 Explain how the college experience increases racial/ethnic diversity awareness

In 2014, the statue of civil rights figure James Meredith was vandalized on the campus of the University of Mississippi. Witnesses reported seeing three young men hanging a noose around the neck of the statue, along with an old Georgia flag with a Confederate battle emblem. Meredith had been the first African American student admitted to the then all-White university in 1962. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling granted Meredith’s enrollment, which state and university officials resisted. Two people were killed and many injured during campus riots. President John Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy ordered hundreds of federal authorities to restore order and to escort Meredith onto campus.

Responding to the vandalism, university chancellor Dan Jones said, “These individuals chose our university’s most visible symbol of unity and educational accessibility to express their disagreement with our values. Our response will be an even greater commitment to promoting the values that are engraved on the statue—courage, knowledge, opportunity and perseverance” (Ole Miss/University of Mississippi News 2014). As for Meredith, he believes Mississippi is still the “center of the universe” for the politics of race and income inequality; he said, “I think Mississippi is ready to do the right thing” (quoted in Dave 2014).

The United States is a diverse racial and ethnic society. The U.S. Census (U.S. Census Bureau 2012c) predicts that by 2043, non-Hispanic whites will no longer make up the majority of the U.S. population. Acting Census Bureau director Thomas L. Mesenbourg (U.S. Census Bureau 2012c) describes the United States as a “plurality nation, where the non-Hispanic white population remains the largest single group, but no group is in the majority.” The minority population (Hispanic, Black, Asian, American Indians, and Alaska Natives) is projected to account for 57% of the population by 2060 (U.S. Census Bureau 2012c).

In 2013, 19 million immigrants were naturalized U.S. citizens. In order to be eligible for citizenship, immigrants must meet requirements set by immigration laws. Eligibility includes age (at least 18 years of age or older) and residency (at least 3 or 5 years as a permanent resident), along with other requirements.

© Lucy Nicholson/Reuters/Corbis

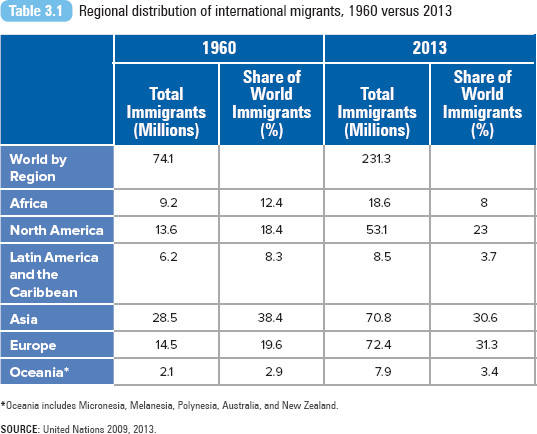

Adding to the diversity of our population are increasing numbers of immigrants, their migration to the United States and throughout the world spurred by the global economy. In 2013, 69% of international migrants lived in high-income countries (nations with an average per capita income of $12,616 or more, such as the United States and Germany) compared with 57% in 1990 (Conner, Cohn, and Gonzalez-Barrera 2013). Population mobility since the middle of the 20th century has been characterized by unprecedented volume, speed, and geographical range (Collin and Lee 2003). At the end of 2013, 232 million people, or about 3% of the world’s population, lived in a country other than their birth country (United Nations 2013). As Zygmunt Bauman (2000) said, “the world is on the move” (p. 77). Regionally, Europe has the largest number of international migrants (about 72 million), followed by Asia (70.8 million) and the United States (53.1 million) (United Nations 2013) (refer to Table 3.1).

Oceania includes Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, Australia, and New Zealand.

SOURCE: United Nations 2009, 2013.

Racial divisions remain a defining feature of our social lives (H. Brown 2013). Complete racial equality and harmony remain elusive in the United States. The high-profile deaths of Black people at the hands of police officers in Ferguson, Missouri; New York; and other U.S. cities have led to public protest and outrage, exposing sharp and uncomfortable divisions about race in our country. In this chapter, we explore how one’s racial and ethnic status serves as a basis of inequality. Like social class, race or ethnicity alters one’s life chances, and members of particular groups experience an increased likelihood of experiencing particular social problems. We begin first with understanding how race and ethnicity are defined.

Defining Race and Ethnicity

From a biological perspective, a race can be defined as a group or population that shares a set of genetic characteristics and physical features. The term has been applied broadly to groups with similar physical features (the White race), religion (the Jewish race), or the entire human species (the human race) (Marger 2002). However, generations of migration, intermarriage, and adaptations to different physical environments have produced a mixture of races. There is no such thing as a “pure” race.

Social scientists reject the biological notions of race, instead favoring an approach that treats race as a social construct. In Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s, Michael Omi and Howard Winant (1994) explain how race is a “concept which signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests by referring to different types of human bodies” (p. 54). Instead of thinking of race as something “objective,” the authors argued that we can imagine race as an “illusion,” a subjective social, political, and cultural construct. In the United States, race tends to be a bipolar construct—White versus non-White. According to the authors, “the meaning of race is defined and contested throughout society, in both collective action and personal practice. In the process, racial categories themselves are formed, transformed, destroyed, and reformed” (Omi and Winant 1994:21). Robert Redfield (1958) says it simply: “Race is, so to speak, a human invention” (p. 67).

Race may be a social construction, but that does not make race any less powerful and controlling (Myers 2005). Omi and Winant (1994) argued that although particular stereotypes and meanings can change, “the presence of a system of racial meaning and stereotypes, of racial ideology, seems to be a permanent feature of U.S. culture” (p. 63).

Ethnic groups are set off to some degree from other groups by displaying a unique set of cultural traits, such as their language, religion, or diet. Members of an ethnic group perceive themselves as members of an ethnic community, sharing common historical roots and experiences. All of us, to one extent or another, have an ethnic identity. Increasingly, the terms race and ethnicity are presented as a single construct pointing to how both terms are being conflated (Budrys 2003).

Martin Marger (2002) explains how ethnicity serves as a basis of social ranking, ranking a person according to the status of his or her ethnic group. Although class and ethnicity are separate dimensions of stratification, they are closely related: “In virtually all multiethnic societies, people’s ethnic classification becomes an important factor in the distribution of societal rewards and hence, their economic and political class positions. The ethnic and class hierarchies are largely parallel and interwoven” (Marger 2002:286).

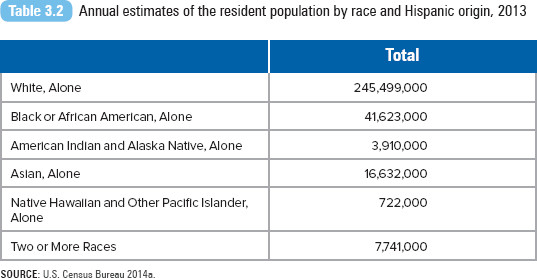

The federal definition of ethnicity is based on the Office of Management and Budget’s 1977 guideline (U.S. Census Bureau 2005), which defines ethnicity in terms of Hispanic/non-Hispanic status, contrary to the conventional social scientific definition as presented in the previous paragraphs. The U.S. Census treats Hispanic origin and race as separate and distinct concepts; as a result, Hispanics may be of any race. Since 2002, Hispanic Americans became the nation’s largest ethnic minority group. The U.S. Census Bureau includes in this category women and men who are Mexican, Central and South American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic. The 2013 ethnic and racial composition estimates of the United States are presented in Table 3.2.

In 2012, the U.S. Census reported that minority births were the majority—50.4% of children younger than age 1 year were Hispanic, Black, Asian, or of mixed race. Non-Hispanic Whites accounted for 49.6% of all births in a 12-month period (U.S. Census Bureau 2012b). Commenting on the report, demographer William Frey (quoted in Tavernise 2012:A1) said, “This is an important tipping point . . . [a] transformation from a mostly white baby boomer culture to a more globalized multiethnic country that we’re becoming.”

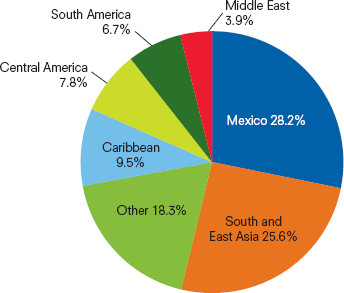

The U.S. Census distinguishes between native and foreign-born residents. Native refers to anyone born in the United States or a U.S. island area such as Puerto Rico or the Northern Mariana Islands or born abroad of a U.S. citizen parent; foreign born refers to anyone who is not a U.S. citizen at birth. Elizabeth Grieco (2010) writes, “The foreign born, through their own diverse origins, will contribute to the racial and ethnic diversity of the United States. How they translate their own backgrounds and report their adopted identities have important implications for the nation’s racial and ethnic composition.” In 2012, among the 40 million foreign born in the United States, most were from Latin America (42.7%, as displayed in Figure 3.1) Brown and Patten 2014a.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2014a.

Figure 3.1 Country of birth for foreign-born population in the United States, 2012

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2014a.

Refugees are defined by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1980 as “aliens outside the United States who are unable or unwilling to return to his/her country of origin for persecution or fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” Data on the number of admitted refugees are collected annually by the U.S. Department of State. In 2013, 69,926 persons were admitted as refugees. Almost 65% of all admitted refugees were from three countries: Burma (24%), Iraq (28%), and Bhutan (13%) (U.S. Department of State 2014).

Tracy Ore (2003) acknowledges that externally created labels for some groups are not always accepted by those viewed as belonging to a particular group. For example, those of Latin American descent may not consider themselves to be “Hispanic.” In this text, I’ve adopted Ore’s practice regarding which racial and ethnic terms are used. In my own material, I use Latino to refer to those of Latin American descent, and Black and African American interchangeably. However, original terms used by authors or researchers (e.g., Hispanic as used by the U.S. Census Bureau) are not altered.

Patterns of Racial and Ethnic Integration

Sociologists explain that ethnocentrism is the belief that one’s own group values and behaviors are right and even better than all others. Feeling positive about one’s group is important for group solidarity and loyalty. However, it can lead groups and individuals to believe that certain racial or ethnic groups are inferior and that discriminatory practices against them are justified. This is called racism.

Though not all inequality can be attributed to racism, our nation’s history reveals how particular groups have been singled out and subject to unfair treatment. Certain groups have been subject to individual discrimination and institutional discrimination. Individual discrimination includes actions against minority members by individuals. Actions may range from avoiding contact with minority group members to physical or verbal attacks against minority group members. Institutional discrimination is practiced by the government, social institutions, and organizations. Institutional discrimination may include segregation, exclusion, or expulsion.

Segregation refers to the physical and social separation of ethnic or racial groups. Although we consider explicit segregation to be illegal and a thing of the past, ethnic and racial segregation still occurs in neighborhoods, schools, and personal relationships. According to Debra Van Ausdale and Joe Feagin (2001),

racial discrimination and segregation are still central organizing factors in contemporary U.S. society. For the most part, Whites and Blacks do not live in the same neighborhoods, attend the same schools at all educational levels, enter into close friendships or other intimate relationships with one another, or share comparable opinions on a wide variety of political matters. The same is true, though sometimes to a lesser extent, for Whites and other Americans of color, such as most Latino, Native and Asian American groups. Despite progress since the 1960s, U.S. society remains intensely segregated across color lines. Generally speaking, Whites and people of color do not occupy the same social space or social status. (p. 29)

Exclusion refers to the practice of prohibiting or restricting the entry or participation of groups in society. In March 1882, U.S. Congressman Edward K. Valentine declared, “The [immigration] gate must be closed” (Gyory 1998:238). That year, Valentine, along with other congressional leaders, approved the Chinese Exclusion Act. From 1882 to 1943, the United States prohibited Chinese immigration because of concerns that Chinese laborers would compete with American workers. Through the 1940s, immigration was defined as a hindrance rather than a benefit to the United States.

Jim Crow laws mandated the segregation of whites and blacks in public facilities, schools, and transportation in U.S. Southern states. The laws were enforced until 1954 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that the racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 further prohibited racial discrimination, ending Jim Crow laws once and for all.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, [LC-DIG-fsa-8a26761 ]

Finally, expulsion is the removal of a group by direct force or intimidation. Native Americans in the United States were forcibly removed from their homelands by early settlers and the federal government before and after the American Revolutionary War. During the 1830s, members of the Cherokee and other nations were forcibly relocated to government-designated Indian territory (present-day Oklahoma). Their journey is known as the Trail of Tears, where thousands died along the way. In 2006, journalist Eliot Jaspin documented the extent of racial expulsion that occurred in towns from Central Texas through Georgia. After the Civil War through the 1920s, White residents expelled nearly all Black persons from their communities, usually using direct physical force. Thirteen countywide expulsions were documented in eight states between 1864 and 1923 in which 4,000 Blacks were driven out of their communities.

Sociological Perspectives on RACIAL AND ETHNIC Inequalities

Functionalist Perspective

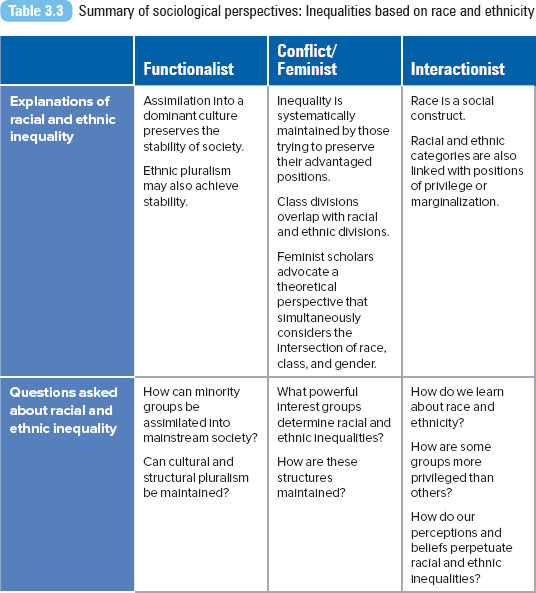

Theorists from the functionalist perspective believe that the differences between racial and ethnic groups are largely cultural. The solution is assimilation, a process where minority group members become part of the dominant group, losing their original distinct group identity. This process is consistent with America’s image as the “melting pot.” Milton Gordon (1964) presents a seven-stage assimilation model that begins first with cultural assimilation (change of cultural patterns, e.g., learning the English language), followed by structural assimilation (interaction with members of the dominant group), marital assimilation (intermarriage), identification assimilation (developing a sense of national identity, e.g., identifying as an American, rather than as an Asian American), attitude receptional assimilation (absence of prejudiced thoughts among dominant and minority group members), behavioral receptional assimilation (absence of discrimination; e.g., lower wages for minorities would not exist), and finally civic assimilation (absence of value and power conflicts).

Assimilation is said to allow a society to maintain its equilibrium (a goal of the functionalist perspective) if all members of society, regardless of their racial or ethnic identity, adopt one dominant culture. This is often characterized as a voluntary process. Critics argue that this perspective assumes that social integration is a shared goal and that members of the minority group are willing to assume the dominant group’s identity and culture, assuming that the dominant culture is the one and only preferred culture (Myers 2005). The perspective also assumes that assimilation is the same experience for all ethnic groups, ignoring the historical legacy of slavery and racial discrimination in our society.

Assimilation is not the only means to achieve racial/ethnic stability. Other countries maintain pluralism, where each ethnic or racial group maintains its own culture (cultural pluralism) or a separate set of social structures and institutions (structural pluralism). Cultural pluralism is also referred to as multiculturalism. Switzerland, which has a number of different nationalities and religions, is an example of a pluralistic society. The country, also referred to as the Swiss Confederation, has four official languages: German, French, Italian, and Romansh. Relationships between each ethnic group are described for the most part as harmonious because each of the ethnically diverse parts joined the confederation voluntarily seeking protection (Farley 2005). In his examination of pluralism in the United States, Min Zhou (2004) notes, “As America becomes increasingly multiethnic, and as ethnic Americans become integral in our society, it becomes more and more evident that there is no contradiction between an ethnic identity and an American identity” (p. 153).

Conflict Perspective

According to sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois (1996), perhaps it is wrong “to speak of race at all as a concept, rather than as a group of contradictory forces, facts and tendencies” (p. 532). The problem of the 20th century, wrote Du Bois, is “the color line.”

Conflict theorists focus on how the dynamics of racial and ethnic relations divide groups while maintaining a dominant group. The dominant group may be defined according to racial or ethnic categories, but it can also be defined according to social class. Instead of relationships being based on consensus (or assimilation), relationships are based on power, force, and coercion. Ethnocentrism and racism maintain the status quo by dividing individuals along racial and ethnic lines (Myers 2005).

Drawing upon Marx’s class analysis, Du Bois was one of the first theorists to observe the connection between racism and capitalist-class oppression in the United States and throughout the world. He noted the link between racist ideas and actions to maintain a Eurocentric system of domination (Feagin and Batur 2004). Du Bois (1996) wrote,

Throughout the world today organized groups of men by monopoly of economic and physical power, legal enactment and intellectual training are limiting with great determination and unflagging zeal the development of other groups; and that the concentration particularly on economic power today puts the majority of mankind into a slavery to the rest. (p. 532)

Marxist theorists argue that immigrants constitute a reserve army of workers, members of the working class performing jobs that native workers no longer perform. Michael Samers (2003) suggests that immigrants are a “quantitatively and qualitatively flexible labour force for capitalists which divides and weakens working class organization and drives down the value of labour power” (p. 557). Capitalist businesses profit from migrant workers because they are cheap and flexible—easily hired during times of economic growth and easily fired during economic recessions. In 2013, approximately 60,000 immigrants worked in the federal detention centers, working for 13 cents an hour. Immigrants held in local county jails also worked for free or in exchange for sodas or candy. Their work usually involves meal preparation or janitorial work. This labor practice, though voluntary and cost-saving (about $40 million per year for federal detention centers), has come under attack by detainees and immigrant advocates (Urbina 2014).

Hana Brown (2013) posits a racialized conflict theory regarding the development of welfare policies. Her use of the term racialized (versus racial) emphasizes the constructed nature of race. Racialized conflicts are “a series of events that draw boundaries based on racial difference, polarize political groups along racial lines and involve explicitly race-based claims” (p. 401). Brown predicts several effects of racialized conflict on the formation of welfare policy. First, Whites may feel threatened by a larger or growing minority population and may perceive that minorities are too reliant on public assistance. These beliefs become institutionalized in the political discourse, transforming welfare into a racialized issue. Finally, racialized conflict divides political groups along racial lines and encourages political leaders to exploit the existing racialized tensions in their favor.

Brown offers empirical support of her hypotheses based on Georgia’s 1993–1994 welfare reform. Georgia’s welfare legislation was preceded by a controversial proposal by Governor Zell Miller to remove the Confederate emblem from the state flag. Response to his proposal was racially divided, with the majority of Whites opposing and the majority of Blacks supporting the governor. The flag proposal never materialized, but it ignited racial tension and racialized the state’s political discourse. Whites felt threatened by and resentful of Blacks, and this affected the welfare debate. According to H. Brown (2013), Miller’s decision to shift his attention from the state flag to welfare reform “proved a politically convenient way to appeal to white resentment and threat, exploit the prevailing racial discourses, and resurrect his political career” (p. 421). Georgia passed one of the strictest and most punitive welfare programs emphasizing work and education.

Feminist Perspective

Feminist theory has attempted to account for and focus on the experiences of women and other marginalized groups in society. Feminist theory intersects with multiculturalism through the analysis of multiple systems of oppression, not just gender, but including categories of race, class, sexual orientation, nation of origin, language, culture, and ethnicity. Most notably, Patricia Hill Collins’s (2000) Black feminist theory emerges from this perspective. Black feminists identify the value of a theoretical perspective that addresses the simultaneity of race, class, and gender oppression.

Black feminist scholars note the misguided application of traditional feminist perspectives of “the family,” “patriarchy,” and “reproduction” to understand the experience of Black women’s lives. Black women do not lead parallel lives, but rather lead different lives. British scholar Hazel Carby (1985) argues that because Black women are subject to simultaneous oppression based on class, race, and patriarchy, the application of traditional (White) feminist perspectives is not appropriate and is actually misleading in attempts to comprehend the true experience of Black women. As an example, Carby (1985) analyzes an article on women in third-world manufacturing. Carby highlights how the photographs accompanying the article are of “anonymous Black women.” She observes, “This anonymity and the tendency to generalize into meaninglessness, the oppression of an amorphous category called ‘Third World Women,’ are symptomatic of the ways in which the specificity of our experiences and oppression are subsumed under inapplicable concepts and theories” (Carby 1985:394).

Political scientist Maria Chávez (2011) documented how Latina attorneys experience workplace marginalization and discrimination due to the unique intersection of their racial, gender, and class identities. Latina attorneys, Chávez notes, experience a deep sense of professional isolation. Female attorneys lack social capital and earn less than their male counterparts. Female attorneys may face gender bias in the courts or experience sexual harassment in the workplace. She explains,

Being the only Latina in a particular work environment in and of itself would not be so isolating if it were an accepting environment . . . . many times the professional and community environments in which they function are filled with sexist and/or racist people–filled with a negative culture that contributes to an increase in a Latina’s sense of isolation. (p. 97)

Chávez reports that according to the American Bar Association, 100% of women of color quit practicing law or move into a different position after eight years of practice.

Interactionist Perspective

Sociologists believe that race is a social construct. We learn about racial and ethnic categories of White, Black, Latino, Asian, Native American, and immigrant through our social interaction. The meaning and values of these and other categories are provided by our social institutions, families, and friends (Ore 2003). Refer to page 75 for a discussion of children’s literature as a source of racial and ethnic identity. As much as I and other social scientists inform our students about the unsubstantiated use of the term race, for most students, race is real. The term is loaded with social, cultural, and political baggage, making deconstructing it difficult to accomplish.

Social scientists have noted how people are raced, how race itself is not a category but a practice. Howard McGary (1999) defines the practice as “a commonly accepted course of action that may be over time habitual in nature; a course of action that specifies certain forms of behavior as permissible and others impermissible, with rewards and penalties assigned accordingly” (p. 83). In this way, racial categories and identities serve as intersections of social beliefs, perceptions, and activities that are reinforced by enduring systems of rewards and penalties (Shuford 2001). Racial practices are not uniform. For example, while in the United States we are accustomed to racial categorizations, for example, the Census Bureau’s race measurement, France’s census does not include measures for race, ethnicity, or religion.

Individuals are attempting to redefine racial boundaries by proposing the creation and acknowledgment of a new racial category: multiracial, or mixed race. This is different from other ethnic movements that work within the existing racial frameworks. For example, Latinos may challenge the meaning and use of the Census category Hispanic, but they are not trying to create a new racial identity (DaCosta 2007). Members of the multicultural movement advocate the formal acceptance of the multiracial category on U.S. Census and other governmental forms and have also worked on broader issues of racial and social justice (Bernstein and De la Cruz 2009).

Scholars have also observed the phenomenon of ethnic attrition, individuals choosing not to self-identify as a member of a particular ethnic group. Brian Duncan and Stephen Trejo (2011) found that about 30% of third-generation Mexican youth in their study failed to identify as Mexican, choosing instead to identify as White. These youth were more likely to have parents with higher levels of educational attainment and have more years of schooling themselves than youth who identified as Mexican. Scholars of race in Latin America have also confirmed patterns of intergenerational Whitening. Highly educated non-White Brazilians were found to be more likely to label their children White than less-educated non-White Brazilians (Schwartzman 2007).

A summary of all theoretical perspectives is provided in Table 3.3.

The Consequences of Racial and Ethnic Inequalities

U.S. Immigration: Past and Present

Most U.S. families have an immigration history, whether it is based upon stories of relatives as long as four generations ago or as recent as the current generation. Immigration involves leaving one’s country of origin to move to another. Though immigration has always been a part of U.S. history, the recent wave of immigration, particularly at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, has led to the observation that we are in the “age of migration” (Castles and Miller 1998).

The regulation of immigration became a federal responsibility in 1875, and the Immigration Service was established in 1891. Before this, all immigrants were allowed to enter and become permanent residents. The Great Wave of immigration occurred from 1900 to 1920, when nearly 24 million immigrants, mostly European, arrived in the United States. Congress passed a national immigrant quota system in 1921, limiting the number of immigrants by national groups based on their representation in U.S. Census figures. The quota system, along with the Depression and World War II, slowed the flow of immigrants for several decades.

In 1965, Congress replaced the national quota system with a preference system designed to reunite immigrant families and attract skilled immigrants. Most of the immigrants who arrived after 1970 were from Latin America and Asia. Legislative reforms continued through the 1990s, targeting amnesty policies for illegal aliens (Center for Immigration Studies 2009). Despite the events of September 11, 2001, and a recent federal crackdown on illegal immigration, the United States still has the most open immigration policy in the world.

Most immigrants are motivated by the global economics of immigration—men and women will move from low-wage to high-wage countries in search of better incomes and standards of living. Labor migration, the movement from one country to another for employment, has been a part of U.S. history, beginning with Chinese male workers brought to build railroads in the 1800s. These men never brought their families or had any intention of staying after their work was completed.

In their analysis of migration trends, Gary Hytrek and Kristine Zentgraf (2007) note how an increasing number of highly skilled laborers are moving from less developed areas around the world to the United States and Europe. These migrants are more likely to return to their place of birth or move on to a third country. Migration tends to occur between geographically proximate countries—for example, Turkish and North African migration to Western Europe and Mexican and Central American migration to the United States.

In 2012, there were 40.8 million foreign-born individuals in the United States. This is the highest number of foreign born ever recorded in U.S. history. Steven Camarota (2007), reporting for the Center for Immigration Studies, notes that one of the striking patterns of recent immigration is the lack of diversity among immigrants themselves. Immigrants from Mexico and South and East Asia account for the majority of the foreign-born population. Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for an overview of the U.S. immigrant population.

The United Nations uses the analogy of multiple doors of a house to describe the different ways migrants enter a country. Migrants can enter a house through the front door (as permanent settlers), the side door (temporary visitors and workers), or the back door (irregular or illegal migrants). Back-door migrants have been the recent focus of political and economic debate.

The number of unauthorized or illegal immigrants peaked at 12 million in 2007. As of 2010, the number had declined to 11.2 million (Passel and Cohn 2012; Krogstad and Passel 2014). The majority of legal or illegal immigrants in the United States are from Mexico. The number of unauthorized Mexican immigrants has been declining since 2007. According to Jens Manuel Krogstad and Jeffrey Passel (2014), as of 2012 there were 5.9 million unauthorized Mexican immigrants in the United States, compared with a peak of 7 million in 2007. They attribute this emigration decline to the Great Recession, declining job opportunities in the housing and construction industry, increasing border enforcement, a rise in deportations, and increasing dangers associated with border crossings.

In Focus

Multicultural Children’s Literature

Children’s literature is an important socializing agent about race. Research has confirmed how children prefer books with subject matter and characters relating to their personal experiences and characteristics (Purves and Beach 1972). Consider, for example, the main characters of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. The U.S. cover for Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban features Harry and Hermione, two main White characters riding a hippogriff. But imagine for a moment if Harry were depicted as a Black teenager or Hermione as a Latina. What impact might that have for Black and Latino/a children? How would they respond to characters who look like them?

Educators have criticized the absence of racial and ethnic diversity and the promotion of Whiteness in children’s literature. According to children’s book author Walter Dean Myers (2014), the inclusion of racially diverse characters informs us about our own race and the race of others.

Books transmit values. They explore our common humanity. What is the message when some children are not represented in those books? . . . Where are the future white loan officers and future politicians going to get their knowledge of people of color? Where are black children going to get a sense of who they are and what they can be? (p. 6)

Educator Violet Harris (1990: 552) warns, “If African American children do not see reflections of themselves in school texts or do not perceive any affirmation of their cultural heritage in those texts, then it is quite likely that they will not read or value school as much.”

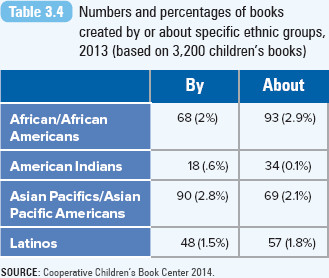

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison compiles a list of children’s books published in the United States that were created by and about people of color, including African Americans, American Indians, Asian Pacific Islanders, and Latinos. The center reviewed 3,200 children’s books published in 2013 and reported the numbers (and percentages) of books created by or about specific racial/ethnic groups (refer to Table 3.4).

SOURCE: Cooperative Children’s Book Center 2014.

The center advocates multicultural literature, defined as literature that focuses on people of color, religious minorities, regional cultures, the disabled, or the aged (Harris 1996). According to the center (Cooperative Children Book’s Center, 2014),

the more [multicultural] books there are, especially books created by authors and illustrators of color, the more opportunities librarians, teachers, and parents and other adults have of finding outstanding books for young readers and listeners that reflect dimensions of their lives, and give a broader understanding of who we are as a nation.

Is the impact of children’s literature on racial and ethnic construction overstated? Why or why not? How was race or ethnicity constructed in your favorite childhood books, movies, or television programs?

Exploring social problems

The U.S. Immigrant Population

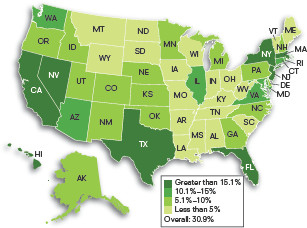

U.S. Data Map 3.1 Percentage of foreign-born population by state, 2012

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2014a.

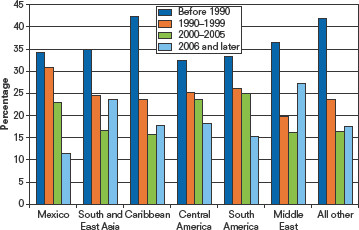

Figure 3.2 Percentage distribution of foreign-born population by region of birth and date of arrival, 2012

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau 2014b.

What Do You Think?

The U.S. immigrant population is concentrated in five states: California, New York, New Jersey, Nevada, and Hawaii. Though not shown here, California is home to the most undocumented immigrants, estimated at 2.5 million. Texas is the next largest with 1.7 million undocumented immigrants.

Figure 3.2 displays the percentage distribution of foreign born by their region of birth. The data reveal a decline in the percentage of Mexican, Caribbean, and South American immigrants over the four time periods. There has been a shift in where immigrants are coming from.

Which groups have shown an increase in the percentage of immigrants over the same time period?

The Immigrant Experience

While most immigrants come to the United States to pursue the promise of the freedom of choice, education, economic opportunity, and a better quality of life, their lives are often filled with challenges and problems.

The post-2000 wave of immigrants included men and women with lower educational attainment—34% have less than a high school education. Considering the population of illegal immigrants, the foreign-born population as a whole is much less educated than the native-born population. Camarota (2007) observes that these individuals’ lower educational attainment has “enormous implications” for their economic and social integration. A larger proportion of immigrants than those who are native born have low incomes, lack health insurance, and rely on social assistance programs.

Data from the U.S. Census Current Population Survey reveals that 15.1% of immigrants lived in poverty in 2011. The higher incidence of poverty among immigrants as a group has increased the overall size of the population living in poverty. The lack of health insurance is also a significant problem for immigrants—34.1% of foreign-born individuals lack insurance compared with 13.8% of natives. Illegal immigrants are not eligible for Medicare, and legal immigrants must wait five years to qualify for the program. Camarota (2007) notes that immigrants’ low rate of health insurance is associated with a lower level of education and their employment. Unskilled immigrants are likely to work at jobs that do not offer health insurance, and they are often unable to purchase insurance on their own.

These Mexican farm workers are weeding a field in California’s Imperial Valley. They are paid to work in the fields for about $9.00 an hour.

John Moore/Getty Images

Immigrant labor is concentrated in construction, cleaning and maintenance, production, and farming occupations. Illegal immigrants are employed in similar areas: construction, building cleaning and maintenance, food preparation and service, transportation and moving, and agriculture. There are an estimated 8 million illegal immigrants in the labor force (Passel and Cohn 2012). Foreign-born workers are especially susceptible to abuse, stress, and unsafe working conditions due to their overrepresentation in dangerous industries, combined with their undocumented worker status, lack of training, and lack of English literacy (Migrant Clinicians Network 2009). As reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013), in 2012, Hispanics accounted for the largest proportion (39%) of foreign-born workers who died on the job. A total of 824 foreign-born workers died of fatal work injuries in 2012.

With the exception of the agricultural sector, the majority of workers in occupations where immigrants are concentrated are native-born workers (Camarota and Jensenius 2009). Yet, no single occupation is composed entirely of immigrant labor (Camarota 2009). Immigration has been found to have a negative effect on the wages of native-born Americans, primarily in low-paying, low-skilled occupations, reducing wages by an estimated 4% to 7% (Camarota 2009). As Camarota (2007) observes, “A central question for immigration policy is whether we should allow in so many people with little education—increasing job competition for the poorest American workers and the population needing assistance” (p. 39).

Carola Suárez-Orozco et al. (2011) report that there are an estimated 5.5 million children and adolescents living with illegal immigrant parents. Suárez-Orozco and her colleagues documented how the children of illegal immigrant parents lack access to quality educational (child care, preschool, school, and higher education) and employment opportunities. Despite having the same level of commitment to their children’s education as authorized legal parents, illegal parents have fewer resources and skills (low social and educational capital) to help their children realize their educational goals. In addition, illegal parents’ fear of deportation leads to lower levels of engagement with teachers or schools. Suárez-Orozco et al. conclude, “For millions of children and youth growing up in unauthorized families, the American Dream and the promise of a better tomorrow have become an elusive mirage” (p. 462).

As it has increased its immigration enforcement (including detainment and deportation), the Department of Homeland Security has been criticized for targeting immigrants with minor offenses, sometimes breaking up families in the process. Human Rights Watch (2009) reported that since stricter deportation laws were passed in 1996, most immigrants have been deported for minor offenses (such as marijuana possession or traffic offenses). The new laws disallowed judges to consider in deportation cases noncitizens’ ties to the United States, including family, business or property ownership, and service in the U.S. armed forces. Among legal immigrants who were deported, over 70% had been convicted for nonviolent crimes. Many had lived in the United States for years and were separated from family members. Researchers from the Urban Institute documented short- and long-term effects on children with deported or detained parents. These children experienced financial, food, and housing hardships in addition to behavioral changes such as changes in eating and sleeping habits and higher degrees of fear and anxiety (Chaudry et al. 2010). The Obama administration promised a more compassionate approach to enforcement that would focus on felony criminal offenders. In 2011, 396,906 immigrants were deported—the largest number in the history of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Fifty-five percent were convicted of felonies or misdemeanors (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement 2011).

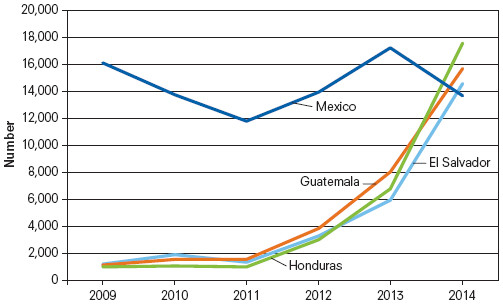

Figure 3.3 Number of unaccompanied alien children by fiscal years 2009–2013

SOURCE: U.S. Customs and Border Protection 2014.

During 2013–2014, there were an estimated 61,581 unaccompanied alien children entering the United States, an increase of more than 23,000 over the previous year (refer to Figure 3.3). The majority of children and families were from the Central American countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Dan Restrepo and Ann Garcia (2014) attributed the increased flow of children to “the interrelated challenges” of regional violence and poverty that adversely affect residents of these countries. The surge of immigration by unaccompanied children was called a crisis, a humanitarian issue, and a threat to border security. U.S. House Republicans argued that the increase was due to the lack of border enforcement and to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) (refer to solutions discussion on p. 86). Restrepo and Garcia (2014) noted that the United States was not alone in experiencing the immigrant influx, as the immigrant surge also occurred in Mexico, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Belize. The flow of immigrants had been increasing since 2011.

Taking a World View

Global Immigration

Migration has been elevated to a top international policy concern (Düvell 2005), largely because of the threat of terrorism and the challenge of global politics. Migrants now depart from and arrive in almost every country in the world. Politically and morally, migration pits two basic principles against each other. On one hand is the right of individuals to move freely across borders for economic or personal reasons, and on the other is the country’s right to self-govern, to regulate its borders, and to determine the difference between a citizen and an alien (Benhabib 2012). Great Britain, Greece, France, Germany, Australia, and other countries have seen an increase in pro- and anti-immigration protests, as well as increased hate crime acts against immigrants.

Riots by immigrants took place in France in 2005 and in Italy during 2008–2010. In Italy, there are 4 million legal immigrants and estimates of more illegal immigrants residing in the country. Flavio Di Giacomo, a spokesman for the International Organization for Migration, described how immigrant workers live in semislavery. The riots, according to Di Giacomo, revealed how “many Italian economic realities are based on the exploitation of low-cost foreign labor, living in subhuman conditions, without human rights” (Donadio 2010a:A7). The African laborers were paid under the table, about $30 a day for picking fruit (Donadio 2010b). Asian and African immigrants in Greece have been the targets of violence and physical attacks since 2010. The violence has been fueled by public discontent over the economy and concern over job losses as well as demonization of immigrants in the press and in the political arena. From a social constructionist’s perspective, immigrants were portrayed as the source of Greece’s economic woes, defining them as a social problem and threat.

Migration flows are regarded as a threat to national and global stability, with some calling for an international migration policy (Düvell 2005). Globalization has intensified the need to coordinate and harmonize government policies. The United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and Japan have increased policy coordination regarding immigration, refugee admissions, and programs to integrate foreigners and their family members already present in each country (Lee 2006). Several countries have instituted immigration quotas and restrictions. In 2014, Swiss voters narrowly approved immigration quotas for European Union citizens. (Switzerland is not a member of the European Union.) Analysts describe the vote as a response to a growing concern that immigrants are eroding the Swiss life style and culture. According to the European Commission, the vote went against the principle of the free movement of people (Baghdjian and Schmieder 2014).

Would you support the closing of our borders to all new immigrants? Why or why not?

Income and Wealth

“Race is so associated with class in the United States that it might not be direct discrimination, but it still matters indirectly,” says sociologist Dalton Conley (Ohlemacher 2006:A6). Data reported by the U.S. Census reveal that Black households had the lowest median income in 2013 ($34,598), or 59% of the median income for non-Hispanic White households ($58,270). The median income for Hispanic households was $40,963, 70% of the median for non-Hispanic White households. Asian households had the highest median income ($67,065), 115% of the median for non-Hispanic White households (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor 2014).

Because of years of discrimination, low educational attainment, high unemployment, or underemployment, Blacks and Hispanics have not been able to achieve the same earnings or level of wealth as White Americans have. In 2011, the average household income for Whites was $67,175. Blacks earned, on average, about 59% of what White households earned, or $39,760. The amount was about the same for Hispanics ($40,007, or 60% of White average household income). The median household wealth of Black households was $6,446, less than one tenth the median net worth of White households ($91,405). Hispanic median net worth was also lower than that of White households at $7,843 (Pew Research Center 2014).

One measure of wealth is home ownership. Home ownership is one of the primary means to accumulate wealth (Williams, Nesiba, and Diaz McConnell 2005). It enables families to finance college and invest in their future. Historically, home ownership grew among White middle-class families after World War II, when veterans had access to government and credit programs that made home ownership more affordable. However, Blacks and other minority groups have been denied similar access because of structural barriers such as discrimination, low income, and lack of credit access. Feagin (1999) identifies how inequality in home ownership has contributed to inequality in other aspects of American life. Specifically, Blacks have been disadvantaged because of their lack of home ownership, particularly in their inability to provide their children with “the kind of education or other cultural advantages necessary for their children to compete equally or fairly with Whites” (Feagin 1999:86).

In 2004, U.S. home ownership reached a record high of 69.2%, with nearly 73.4 million Americans owning their own homes. However, racial gaps in home ownership persist. In 2011, 73.8% of White households owned their own homes, compared with 44.9% of Black and 46.9% of Hispanic households (U.S. Census Bureau 2012a).

Education

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that racial segregation in public schools was illegal. Reaction to the ruling was mixed, with a strong response from the South. A major confrontation occurred in Arkansas, when Governor Orval Faubus used the state’s National Guard to block the admission of nine Black students into Little Rock Central High School. The students persisted and successfully gained entry to the school the next day with 1,000 U.S. Army paratroopers at their side. The Little Rock incident has been identified as a catalyst for school integration throughout the South. Despite resistance to the Court’s ruling, legally segregated education had disappeared by the mid-1970s.

However, a different type of segregation persists, called de facto segregation. De facto segregation refers to a subtler process of segregation that is the result of other processes, such as housing segregation, rather than an official policy (Farley 2005). Here, we clearly see the intersection of race and class. Schools have become economically segregated, with children of middle- and upper-class families attending predominantly White suburban schools and the children of poorer parents attending racially mixed urban schools (Gagné and Tewksbury 2003). Researchers, teachers, and policy makers have all observed a great disparity in the quality of education students receive in the United States (for more on social problems related to education, turn to Chapter 8). Educational systems reinforce patterns of social class inequality and, along with it, racial inequality (Farley 2005).

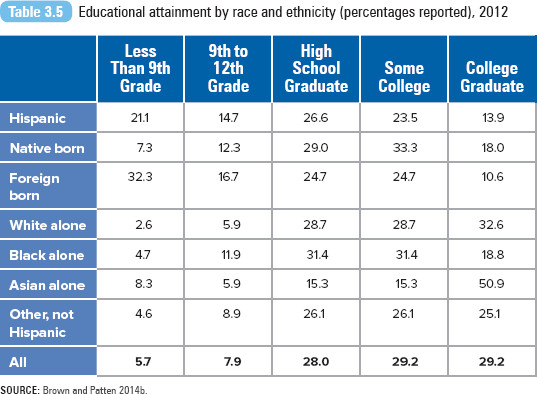

Though Latinos have the lowest educational achievement rates compared with all other major racial and ethnic groups in the United States (refer to Table 3.5), there has been a recent increase in rates of high school completion and college enrollment. Richard Fry and Paul Taylor (2013) reported that for the class of 2012, 69% of Hispanic high school graduates enrolled in college, compared with 67% of their White student peers. This percentage is an increase from what was reported for the class of 2000, when only 49% of Hispanic high school graduates enrolled in college. Fry and Taylor attribute the college enrollment increase to two structural factors: a tough and competitive job market and the importance Latino families place on a college education. Yet, Fry and Taylor also report that young Latinos are less likely than White students to complete a bachelor’s degree. They cite U.S. Census Bureau data showing how only 11% of 22- to 24-year-old Latinos finish a four-year degree, compared to 22% of White students of the same age.

Much of the research on the achievement gap between Latinos and White students has focused on the characteristics of the students (family income, parents’ level of education). However, according to the Pew Hispanic Center (Fry 2005), we need to also consider the social context of Hispanic students’ learning, noting how educators and policy makers have more influence over the characteristics of their schools than over the characteristics of students. Based on their state and national assessment of the basic characteristics of public high schools for Hispanic and other students, the Pew Hispanic Center found that Latinos were more likely than Whites or Blacks to attend the largest public high schools (enrollment of at least 1,838 students). More than 56% of Hispanics attend large schools, compared with 32% of Blacks and 26% of Whites. Schools with larger enrollments are associated with lower student achievement and higher dropout rates. In addition, the center reported that Hispanics are more likely to be in high schools with lower instructional resources, including higher student-to-teacher ratios, which has been associated with lower academic performance. Nearly 37% of Hispanics are educated in public high schools with a student–teacher ratio greater than 22 to 1, compared with 14% of Blacks and 13% of White students (Fry 2005).

In June 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court, voting 5 to 4, invalidated the use of race to assign students to public schools, even if the goal was to achieve racial integration of a district’s schools. The ruling addressed public school practices in Seattle, Washington (where 41% of all public school students are White), and Louisville, Kentucky (where two thirds of all public school students are White). Legal experts and educators were divided about whether the ruling affirmed or betrayed Brown v. Board of Education. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts asserted, “Simply because the school districts may seek a worthy goal [racial integration] does not mean they are free to discriminate on the basis of race to achieve it.” Though he voted with the majority, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy said in a separate statement that achieving racial diversity and addressing the problem of de facto segregation were issues that school districts could constitutionally pursue as long as the programs were “sufficiently ‘narrowly tailored’” (Greenhouse 2007:A1).

Health

“Although race may be a social construct, it produces profound biological manifestations through stress, decreased services, decreased medications, and decreased hospital procedures” (Gabard and Cooper 1998:346). Racial disparities in access to health care and outcomes are pervasive, according to Sara Rosenbaum and Joel Teitelbaum (2004). The issue is twofold: (1) access to health care and (2) the quality of care received once in the system.

First, the researchers point to this nation’s approach to health insurance as a system that “significantly discriminates against racial and ethnic minorities” (Rosenbaum and Teitelbaum 2004:138). Data reveal how in a voluntary, employment-based health care system, racial and ethnic minority group members are more likely to be uninsured or publicly insured. In 2013, White non-Hispanics had the lowest uninsured rate (9.8%), compared with Blacks (15.9%), Asians (14.5%), and Hispanics (24.3%) (Smith and Medalia 2014). These disparities continue into old age—among those 65 years or older, non-Latino White seniors are more likely to have a private or employer-based supplemental health policy in addition to their Medicare coverage, whereas minority seniors are six to seven times more likely to have Medicaid (public assistance) in addition to Medicare. The Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions or premium tax credits for exchange coverage (with full implementation in 2015) have the potential to increase insurance access for racial and ethnic minorities.

Second, the researchers observe that even after minority patients enter a particular facility, they are less likely to receive the level of care provided to nonminority patients for the same condition, regardless of their insurance status. For example, Latino and African American patients with public insurance do not receive coronary artery bypass surgery at rates comparable to those of White, publicly insured patients. African American women with breast cancer receive lower-quality cancer care after diagnosis and are delayed in receiving treatments when compared with White women with breast cancer (Parker-Pope 2013). Medicaid-insured African American and Latino children use less primary care (depending usually on emergency treatment), experience higher rates of hospitalization, and die at significantly higher rates than do White children. Though the U.S. government has invested in community-based primary health centers and programs to address these health care gaps, Rosenbaum and Teitelbaum (2004) conclude that these programs can hardly overcome the immense and inaccessible system of specialized and extended health services.

W. Michael Byrd and Linda Clayton (2002) assert that the health crisis among African Americans and poor populations is fueled by a medical-social culture laden with ideological, intellectual and scientific, and discriminatory race and class problems. They believe that America’s health system is predicated on the belief that the poor and “unworthy” of our society do not deserve decent health. Consequently, health professionals, as well as research and educational systems, engage in what they describe as “self serving and elite behavior” that marginalizes and ignores the problems of health care for minority and disadvantaged groups. They caution that our failure to address, and eventually resolve, these race- and class-based health policy, structural, medical-social, and cultural problems plaguing the American health care system could potentially undermine any possibility of a level playing field in health and health care for African American and other poor populations—eroding at the front end the very foundations of American democracy (Byrd and Clayton 2002:572–73).

Responding to Racial and Ethnic Inequalities

Immigration Policy

In 2006 and 2007, the George W. Bush administration proposed comprehensive immigration reforms (CIR). Illegal immigration became a primary concern for Americans, responding to the threat of terrorism and increasing competition in a struggling economy. While acknowledging the country’s immigration heritage, the administration proposed strengthening security at our southern border with Mexico and establishing a temporary worker program without the benefit of amnesty. The plan was criticized for creating a class of workers who would never become fully integrated in U.S. society and for focusing specifically on Mexican workers, ignoring all other immigrant groups.

In 2009, similar to the Bush plan, Obama officials promoted the need for tougher enforcement laws against illegal immigrants and employers who hire them, a streamlined system for legal immigration, and a system for illegal immigrants to earn legal status (Preston 2009). However, the administration’s continuing focus on punitive enforcement strategies has been criticized for failing to encourage and promote assimilation among immigrants and their children. Nationwide polls show broad support for tougher border and workplace enforcement, while also establishing an opportunity for citizenship.

After the U.S. Congress was unable to pass a bipartisan immigration bill, the states took matters into their own hands, debating similar immigration issues in their own state legislatures (Preston 2007). Between 2005 and 2011, more than 8,000 bills related to immigration were introduced throughout the country, and approximately 1,700 were signed into law (National Conference of State Legislatures 2011). These laws addressed a range of immigration issues—the use of unauthorized illegal workers, the use of false identification (e.g., Social Security), and the extension of education and health care benefits to legal immigrants. Arizona legislators passed SB 1070, the toughest immigration bill, in 2010, requiring local law enforcement agencies and officers to demand proof of citizenship from suspected illegal immigrants. Failure to carry proper documentation, even if one is a legal immigrant, is defined as a misdemeanor.

On International Workers Day, these Arizona marchers show their support for immigrants and immigration reform.

© jcamilobernal/iStock

In 2011, 31 states introduced legislation replicating all or part of SB 1070. Voters in five states—Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Utah—successfully passed immigration laws modeled after SB 1070. In 2012, the Supreme Court upheld part of Arizona’s law, permitting the “show me your papers” provision, while ruling that the state could not pursue policies that undermined or conflicted with federal law, for example, by making it a crime under state law for immigrants to fail to register under a federal law, making it a state crime for illegal immigrants to work, and allowing police to arrest individuals without warrants (Liptak 2012). The decision will affect similar laws in the five other states. Civil rights groups and immigration advocates expressed concern that the justices’ decision would encourage racial profiling. The Court suggested that it would be open to hearing new challenges based on any adverse impact its ruling might have on the civil rights of Arizona residents (Preston 2012a).

The impact of immigration especially for youth and young adults has been the focus of federal and state government debate. Second generation applies to those born in the United States to one or more foreign-born parents. Based on key measures of socioeconomic attainment (income, college graduation, homeownership, and poverty rates), most second-generation Americans are better off than first generation Americans. Their characteristics resemble the full U.S. adult population (Pew Research 2013). In contrast, the 1.5 generation refers to individuals who immigrated to the United States as a child or an adolescent. The parents of the 1.5 generation are foreign born. Members of the 1.5 generation are described as living between two worlds; though they spend most of their life in the United States, they still are not legal citizens.

Through executive action, in 2012 the Obama administration blocked the deportation of more than 800,000 migrants who came to the United States before age 16 (Preston and Cushman 2012; White House 2012). The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) allows those who have lived in the United States for at least five years and are currently enrolled in school, high school graduates, or military veterans in good standing to work legally and to obtain driver’s licenses. An immigrant convicted of a felony, a serious misdemeanor, or three less serious misdemeanors would not be eligible. The Pew Hispanic Center estimated that as many as 1.4 million immigrants would be eligible for this measure (Preston and Cushman 2012), most of them (about 460,000) living in California (Preston 2012b).

As congressional gridlock on immigration continued in 2014, President Obama announced a series of executive actions that would grant up to 5 million unauthorized immigrants protection from deportation. His order created a deferred action program for parents of U.S. citizens. Undocumented immigrant parents would have to pass background checks, pay fees, and show that their child was born before the president’s announcement. The president also announced the extension of DACA eligibility to men and women who entered the United States as children before January 2010, regardless of how old they are today. DACA relief will be extended to three years (White House 2014). In response, a group of 20 states filed a federal lawsuit, claiming that the president had overstepped his executive authority.

Affirmative Action

Since its inception 50 years ago, affirmative action has been a “contentious issue on national, state, and local levels” (Yee 2001:135). Affirmative action is a policy that has attempted to improve minority access to occupational and educational opportunities (Woodhouse 2002). No federal initiatives enforced affirmative action until 1961, when President John Kennedy signed Executive Order 10925. The order created the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and forbade employers with federal contracts from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, or religion in their hiring practices. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin by private employers, agencies, and educational institutions receiving federal funds (Swink 2003).

In June 1965, during a graduation speech at Howard University, President Johnson spoke for the first time about the importance of providing opportunities to minority groups, an important objective of affirmative action. According to Johnson (1965),

you do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him to the starting line of a race and then say, “You are free to compete with all others” and still justly believe you have been completely fair. Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates. This is the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity. (p. 366)

Employment

In September 1965, President Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, which required government contractors to “take affirmative action” toward prospective minority employees in all aspects of hiring and employment. Contractors are required to take specific proactive measures to ensure equality in hiring without regard to race, religion, and national origin. The order also established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), charged with enforcing and monitoring compliance among federal contractors. In 1967, President Johnson amended the order to include discrimination based on gender (Swink 2003). In 1969, President Richard Nixon initiated the Philadelphia Plan, which required federal contractors to develop affirmative action plans by setting minimum levels of minority participation for federal construction projects in Philadelphia and three other cities (Idelson 1995). This was the first order that endorsed the use of specific goals for desegregating the workplace (Kotlowski 1998), but it did not include fixed quotas (Woodhouse 2002). India’s affirmative action program relies on quotas in the public (government) sector. In Northern Ireland, affirmative action is practiced in public and private sectors, including government contractors, and does not rely on quotas (Muttarak et al. 2013).

According to Dawn Swink (2003), “While the initial efforts of affirmative action were directed primarily at federal government employment and private industry, affirmative action gradually extended into other areas, including admissions programs in higher education” (pp. 214–15). State and local governments followed the lead of the federal government and took formal steps to encourage employers to diversify their workforces.

Opponents of affirmative action believe that such policies encourage preferential treatment for minorities (Woodhouse 2002), giving women and ethnic minorities an unfair advantage over White males (Yee 2001). Affirmative action, say its critics, promotes “reverse discrimination,” the hiring of unqualified minorities and women at the expense of qualified White males (Pincus 2003). Some believe affirmative action has not worked and ultimately results in the stigmatization of those who benefit from the policies (Heilman, Block, and Stahatos 1997; Herring and Collins 1995).

Proponents argue that only through affirmative action policies can we address the historical societal discrimination that minorities experienced in the past (Kaplan and Lee 1995). Although these policies have not created true equality, there have been important accomplishments (Tsang and Dietz 2001). As a result of affirmative action, women and people of color have gained increased access to forms of public employment and education that were once closed to them (Yee 2001). Yet, research indicates that ethnic minorities and women do not have an unfair advantage over White men. Women and ethnic minorities are not receiving equal compensation compared with White males with similar education and background (Tsang and Dietz 2001). Wage disparities and job segregation continue to exist in the workplace (G. L. A. Harris 2009).

G. L. A. Harris (2009) explains that although the record on affirmation action is mixed, there is evidence that without the policy and the use of gender, race, and/or other ethnicity as part of the employment hiring process, the employment status of women and underrepresented minorities would be worse. Affirmative action has been the “only comprehensive set of policies that has given women and people of color opportunities for better paying jobs and access to higher education that did not exist before” (Yee 2001:137). There is also evidence of how White employees benefit from the inclusion of these groups in the workplace; for example, companies with more than 100 employees with affirmation action programs have higher earnings for Whites, women, and minority employee groups (Pincus 2003).

Shawn Woodhouse (1999, 2002) argues that the differences in individual perceptions of affirmative action policy may be related to the differences of racial group histories and socialization experiences. She writes,

Based upon these rationalizations, it is implicit that individuals interpret affirmative action through an ethnic specific lens. In other words, most individuals will assess their group condition when considering contentious legislation such as affirmative action because after all, a group’s history impacts its view of American society. (Woodhouse 2002:158)

Voices in the Community

Sofia Campos

Sofia was 6 years old when she moved with her family from Peru to the United States. Sofia and her siblings quickly adjusted to their new lives in Los Angeles. It was not until she was accepted into UCLA that Sofia discovered that her family had immigrated illegally. Her mother revealed the secret when Sofia needed a Social Security number to apply for federal scholarships. Sofia explains, “I was angry at first that she hadn’t told me. But I understand why they did that. It was to protect us for as long as they could, like any parent would do with their child” (quoted in Del Barco 2012).

Though she was able to pay in-state tuition (California is one of 13 states that allows undocumented students to pay in-state tuition), she could not receive any scholarships. Sophia worked her way through college and in five years, graduated with a double major in International Developmental Studies and Political Science.

Sofia began her activism while she was at UCLA. Inspired by her own experiences, her focus was on undocumented student rights. “That hateful language, you know, like ‘illegal, alien, wetback leach’. People were talking about my brother, my sister, my mom, my dad. How can these people, who don’t know me at all, who don’t know the love that exists within my family, how can you be just so hateful?” (quoted in Del Barco 2012). She was a central figure in several UCLA student organizations, promoting the federal and California versions of the DREAM Act, also known as the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act. Sofia currently serves as the board chair of United We Dream, the largest network of undocumented immigrant youth. In 2014, she was enrolled in a master’s program at MIT (United We Stand 2014).

The DREAM Act was first introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2001. The DREAM Act would enact two major changes in the current law: (1) Certain immigrant students who have grown up in the United States would be permitted to apply for temporary legal status and to eventually obtain permanent legal status and qualify for U.S. citizenship if they went to college or served in the U.S. military, and (2) the federal provision that penalizes states that provide in-state tuition without regard to immigration status would be eliminated. Though the federal DREAM Act has not been passed, 15 states, including California, have passed their own versions of the act, extending in-state tuition and financial aid to undocumented college students.

Opponents of the DREAM Act argue that it is unfair to American-born and legal immigrant college students and their families. What do you think about the DREAM Act proposals? Has your state adopted a DREAM Act?

Education

Based on Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, affirmative action policies have been applied to student recruitment, admissions, and financial aid programs. Title VI permits the consideration of race, national origin, sex, or disability to provide opportunities to a class of disqualified people, such as minorities and women, who have been denied educational opportunities. Affirmative action policies have been supported as remedies for past discrimination as means to encourage diversity in higher education and as a tool for social justice. Such policies also have economic motivations, helping disadvantaged populations achieve economic self-sufficiency. Affirmative action practices were affirmed in the 1978 Supreme Court decision in the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, suggesting that race-sensitive policies were necessary to create diverse campus environments (American Council on Education and American Association of University Professors 2000; Springer 2005).

Although affirmative action has been practiced since the Bakke decision, it has been under attack, particularly via challenges of the diversity argument in the Supreme Court’s decision. The first challenge occurred in one of our most diverse states, California. In 1995, the California Board of Regents banned the use of affirmative action guidelines in admissions. In 1996, California voters followed and passed Proposition 209, the California Civil Rights Initiative, which effectively dismantled the state’s affirmative action programs in education and employment. Also in 1996, a federal appeals court ruling struck down affirmative action in Texas. In the Hopwood v. Texas decision, the ruling referred to affirmative action policies as a form of discrimination against White students. State of Washington voters passed an initiative in 1998 that banned the use of race-conscious affirmative action in schools. In 1999, Florida governor Jeb Bush banned the use of affirmative action in admission to his state’s schools.

The Hopwood ruling led to a decline in the number of minority students enrolling in Texas A&M and the University of Texas (Yardley 2002). California’s state universities experienced a similar drop in minority student applications and enrollment after the Bakke decision and the California Civil Rights Initiative. In response, states have instituted other practices with the goal of increasing minority student recruitment. For example, California and Texas have initiated percentage solutions. In Texas, the top 10% of all graduating seniors are automatically admitted into the University of Texas system. (In 2009, the Texas Legislature voted to put limits on the program, setting enrollment caps on the number of students let in under the rule at 75% of the entering class.) California initiated a similar plan, covering only the top 4% of students, and Florida implemented the One Florida Initiative, allowing the top 20% of graduating high school seniors into the state’s public colleges and universities (Schemo 2001). As of 2014, all three plans remain in effect.

For more than a decade, the University of Michigan’s affirmation action program has been disputed. In 2000, a federal judge upheld the University of Michigan’s program, ruling that “a racially and ethnically diverse student body produces significant educational benefits such that diversity, in the context of higher education, constitutes a compelling governmental interest” (Wilgoren 2000:A32). In 2003, the case was considered by the U.S. Supreme Court, and in a 5 to 4 vote, the Court upheld the University of Michigan’s consideration of race for admission into its law school. Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor stated, “In order to cultivate a set of leaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry, it is necessary that the path to leadership be visibly open to talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity” (Greenhouse 2003:A1). In a separate decision, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 6 to 1, invalidating the university’s affirmative action program for admission into its undergraduate program (Greenhouse 2003). In November 2006, Michigan voters approved Proposal 2, a state constitutional amendment banning consideration of race or gender in public university admissions or government hiring or contracting. Following the state’s challenge to the amendment, in 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Proposal 2, ending race-based admissions at any Michigan state schools or at any other public university in states that have ended the practice. As of 2014, 10 states have outlawed the use of affirmative action in public schools. In most of these states, there has been a decrease in the enrollment of Black and Hispanic students in their most selective colleges and universities (Liptak 2014). To achieve diversity among their student body, colleges and universities will have to focus on student socioeconomic status rather than race.

Encouraging Diversity and Multiculturalism

Accelerated global migration and a resurgence of racial/ethnic conflicts characterized the close of the 20th century (Wittig and Grant-Thompson 1998) and certainly the beginning of the 21st. In an effort to reduce racial/ethnic conflict and to encourage multiculturalism, researchers, educators, political and community leaders, and community members have implemented programs targeting racism and prejudice. Acknowledging that both are complex phenomena with individual, cultural, and structural components, these strategies attempt to address some or most of the components.

Kathleen Korgen, J. Mahon, and Gabe Wang (2003) believe that colleges and universities have the potential to counter the effects of segregated neighborhoods and socialization in primary and secondary schools. Interaction among races thrust together on a college campus provides a unique opportunity for individuals to experience and discuss the aspects of racial/ethnic diversity in their lives, some for the first time (Odell, Korgen, and Wang 2005). Increased interaction with members of different groups should allow individuals an opportunity to learn from others, reducing hostility and prejudice (Shook and Fazio 2008). Interpersonal interactions with racially diverse peers also promote civic engagement, especially if the engagement is diversity related (Bowman 2011).